Easton Avenue/ Main Street Corridor Plan Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nj Transit Fy2019 Obligation (Year-End) Report

NJ TRANSIT FY2019 OBLIGATION (YEAR-END) REPORT T143 ADA--Platforms/Stations COUNTY: Various MUNICIPALITY: Various Funding is provided for the design and construction of necessary repairs to make NJ TRANSIT's rail stations, and subway stations more accessible for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) including related track and infrastructure work. Funding is requested for repairs, upgrades, equipment purchase, platform extensions, and transit enhancements throughout the system and other accessibility repairs/improvements at stations. MPO FUND Phase Year STIP Amount Grant Number Obligation Obligated Unobligated Date Amount Amount COMMENTS DVRPC STATE ERC 2019 $0.230 $0.230 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D44 7/11/2018 $0.230 NJTPA STATE ERC 2019 $0.700 $0.700 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D44 7/11/2018 $0.700 SJTPO STATE ERC 2019 $0.070 $0.070 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D44 7/11/2018 $0.070 TOTALS $1.000 $1.000 $0.000 T05 Bridge and Tunnel Rehabilitation COUNTY: Various MUNICIPALITY: Various This program provides funds for the design, repair, rehabilitation, replacement, painting, inspection of tunnels/bridges, and other work such as movable bridge program, drawbridge power program, and culvert/bridge/tunnel right of way improvements necessary to maintain a state of good repair. MPO FUND Phase Year STIP Amount Grant Number Obligation Obligated Unobligated Date Amount Amount COMMENTS DVRPC STATE ERC 2019 $0.975 $0.975 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D45 7/11/2018 $0.975 NJTPA STATE ERC 2019 $38.429 $38.429 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D45 7/11/2018 $38.429 SJTPO STATE ERC 2019 $0.206 $0.206 $0.000 19-480-078-6310-D45 7/11/2018 $0.206 TOTALS $39.609 $39.609 $0.000 SUMMARY REPORT Section III - Page 1 11/21/2019 10:20:11 AM NJ TRANSIT FY2019 OBLIGATION (YEAR-END) REPORT T111 Bus Acquisition Program COUNTY: Various MUNICIPALITY: Various This program provides funds for replacement of transit, commuter, access link, and suburban buses for NJ TRANSIT as they reach the end of their useful life as well as the purchase of additional buses to meet service demands. -

Livability in Northern New Jersey

A P T J Fall 2010 N m o b i l i t y Livability in Northern New Jersey Livability: A Legacy of Northern N.J. Communities hat’s old is new again. With deep historical separate pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Over roots, many New Jersey towns have 600 modest houses are arranged around the edge of features dating back a century or more— “super blocks” with large interior parks. Located including closely spaced row homes, grid near Fair Lawn Train Station, the 149-acre street layouts, ornate brick and stone neighborhood includes a shopping center, a community Wcommercial buildings and downtown train stations— center, a library and a network of parks and trails. that are being rediscovered as the foundation for Even newer suburban towns in New Jersey are more “livable” and sustainable lifestyles. Ironically, able to draw on the examples of their older neighbors many of the “antiquated” features are being looked and make use of shared infrastructure—notably, the to as wave of the future in community design. state’s extensive mass transit system—to give residents new lifestyle options. P O K T In the midst of economic T I W L L recession, the ethos of getting back I B to basics and reclaiming what is valuable from the past is gaining ground. It is being combined with an appreciation for the power of new technologies and a greater understanding of the environmental impacts of various development patterns and their relation to the transportation system. This issue of Mobility Matters highlights examples of livability and sustainability in communities throughout northern New Jersey that point to new and hopeful directions for the future. -

Directions to the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University

John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce www.heldrich.rutgers.edu Development [email protected] Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning 732.932.4100 and Public Policy Fax: 732.932.3454 30 Livingston Avenue New Brunswick, NJ 08901 Directions to the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University 30 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, NJ ARRIVING VIA TRAIN (New Jersey Transit and/or Amtrak) New Jersey's Transit's Northeast Corridor line (www.njtransit.com ) stops in New Brunswick, NJ. From New York City, take NJ Transit and/or Amtrak to the New Brunswick train station. From Philadelphia, take the R7 Septa line to Trenton, NJ and then take NJ Transit to New Brunswick. The New Brunswick train station is approximately one hour from New York City and Philadelphia. To get to the Center via Amtrak, take Amtrak’s Northeast Regional line (www.amtrak.com ) to either Trenton NJ or Metropark NJ, then transfer to a New Jersey Transit train to New Brunswick. Walking from the Train Station : The Heldrich Center is within 10 minutes walking distance of the station. Cross Albany Street (Route 27) and turn left (going north). Walk a block and a half to George Street. Turn right (going east) onto George Street and walk four blocks to Livingston Avenue. Turn right onto Livingston Avenue; the entrance to the John J. Heldrich Center is on your left at the corner of Livingston Avenue and New Street. For train schedules, link to NJ Transit ( www.njtransit.com ), Amtrak ( www.amtrak.com ) and Septa (www.septa.org ) By Taxi : There is a taxi stand located outside of the New Brunswick station near the Albany Street Entrance. -

Nj Transit Fy2020 Obligation (Year-End) Report

NJ TRANSIT FY2020 OBLIGATION (YEAR-END) REPORT T143 ADA--Platforms/Stations COUNTY: VariousMUNICIPALITY: Various Funding is provided for the design and construction of necessary repairs to make NJ TRANSIT's rail stations, and subway stations more accessible for the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) including related track and infrastructure work. Funding is requested for repairs, upgrades, equipment purchase, platform extensions, and transit enhancements throughout the system and other accessibility repairs/improvements at stations. MPO FUND Phase Year STIP Amount Grant Number Obligation Obligated Unobligated Date Amount Amount COMMENTS DVRPCSTATE ERC 2020 $0.115 $0.115 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D84 8/13/2019 $0.115 NJTPASTATE ERC 2020 $0.350 $0.350 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D84 8/13/2019 $0.350 SJTPOSTATE ERC 2020 $0.035 $0.035 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D84 8/13/2019 $0.035 TOTALS $0.500 $0.500 $0.000 T05 Bridge and Tunnel Rehabilitation COUNTY: VariousMUNICIPALITY: Various This program provides funds for the design, repair, rehabilitation, replacement, painting, inspection of tunnels/bridges, and other work such as movable bridge program, drawbridge power program, and culvert/bridge/tunnel right of way improvements necessary to maintain a state of good repair. MPO FUND Phase Year STIP Amount Grant Number Obligation Obligated Unobligated Date Amount Amount COMMENTS DVRPCSTATE ERC 2020 $0.975 $0.975 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D85 8/13/2019 $0.975 NJTPASTATE ERC 2020 $56.756 $56.756 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D85 8/13/2019 $56.756 SJTPOSTATE ERC 2020 $0.206 $0.206 $0.000 8/13/2019 20-480-078-6310-D85 8/13/2019 $0.206 TOTALS $57.937 $57.937 $0.000 SUMMARY REPORT Section III - Page 1 12/2/2020 NJ TRANSIT FY2020 OBLIGATION (YEAR-END) REPORT T111 Bus Acquisition Program COUNTY: VariousMUNICIPALITY: Various This program provides funds for replacement of transit, commuter, access link, and suburban buses for NJ TRANSIT as they reach the end of their useful life as well as the purchase of additional buses to meet service demands. -

Transit Access to NJ COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES As of 1-13-21 1

Transit Access to NJ COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES as of 1-13-21 1 Sources: NJ COVID-19 Information Hub, nj.com, njtransit.com, google maps, NJTPA CHSTP Visualization Tool (created by Cross County Connection), Greater Mercer TMA, Hunterdon County Transit Guide, Middlesex County Transit Guide, Ocean County Online Bus Tracker App & Schedules, Ridewise of Somerset, Warren County Route 57 Shuttle Schedules Megasites are in BOLD ** site is over 1 mile from transit stop Facility Name Facility Address Phone Bus Other Transit ATLANTIC Atlantic County Health Atlantic Cape Community College (609) 645-5933 NJT Bus # 502 Department 5100 Black Horse Pike NJT Bus # 552 Mays Landing, NJ 08330 Atlanticare Health Services 1401 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 2800 (609) 572-6040 NJT Bus # 565 FQHC Atlantic City, NJ 08401 MediLink RxCare 44 South White Horse Pike N/A NJT Bus # 554 Hammonton, LLC Hammonton, NJ 08037 ShopRite Pharmacy #633 616 White Horse Pike (609) 646-0444 NJT Bus # 508 Absecon, NJ 08201 NJT Bus # 554 Atlantic City Convention 1 Convention Boulevard N/A NJT Bus # 319 Atlantic City Rail Center Megasite Atlantic City, NJ 08401 NJT Bus # 501 Station NJT Bus # 502 NJT Bus # 504 Jitneys: NJT Bus # 505 AC1 NJT Bus # 507 AC3 NJT Bus # 508 AC4B NJT Bus # 509 NJT Bus # 551 NJT Bus # 552 NJT Bus # 553 NJT Bus # 554 NJT Bus # 559 2 Facility Name Facility Address Phone Bus Other Transit BERGEN Bergen New Bridge Medical 230 East Ridgewood Avenue N/A NJT Bus # 168 Center Annex Alternate Care Paramus, NJ 07652 NJT Bus # 752 Facility NJT Bus # 758 NJT Bus # 762 NJT -

Middlesex County Transportation Plan: Projects by Subregion and Municipality

Middlesex County Transportation Plan Proposed and Completed Projects: by Subregion and Municipality November 2013 Middlesex County Transportation Plan: Projects by Subregion and Municipality Table of Contents PROJECTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................ 1 EAST SUBREGION .................................................................................................................................. 2 Carteret Borough....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Metuchen Borough ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Old Bridge Township ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Perth Amboy City ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sayreville Borough..................................................................................................................................................... 5 South Amboy City ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Woodbridge Township ............................................................................................................................................. -

Vision Innovation Dedication 2013 NJ TRANSIT ANNUAL REPORT

You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library 2013 NJ TRANSIT ANNUAL REPORT Vision Innovation Dedication You Are Viewing an Archived Report from the New Jersey State Library Table of Contents Messages ................................................... 04 • Message from the Chairman ........................... 04 • Message from the Executive Director ................ 05 • The Year in Review ........................................ 06 FY2013 Highlights ........................................ 10 • Superstorm Sandy ......................................... 10 • Scorecard .................................................... 14 • Improving the Customer Experience .............. 16 • Service ...................................................... 16 • Equipment Deliveries ................................... 17 • Facilities/Infrastructure ................................ 18 • Studies ......................................................20 • Technology ................................................20 • Safety & Security ...........................................22 • Financial Performance ....................................24 • Corporate Accountability ................................24 • Super Bowl 2014 ............................................26 On-Time Performance ............................... 28 • On-time Performance by Mode ....................... 28 • O n-time Performance Rail Methodology ............29 • O n-time Performance Light Rail Methodology ... 30 • O n-time Performance Bus Methodology ........... -

Welcome to Rutgers University in New Brunswick

Welcome to Rutgers University in New Brunswick Dear Members and Friends of the American Association for Chinese Studies, Huamin Research Center at Rutgers University School of Social Work is honored to host your 2013 annual convention. We look forward to welcoming you to New Brunswick, New Jersey. Rutgers University was established in 1766, and is the only public New Jersey school that is part of the Association of American Universities’ 61 lending research universities. Rutgers University has three campuses (New Brunswick, Camden and Newark) and is comprised of 28 schools and colleges with more than 58,000 students from all 50 states and 125 countries. New Brunswick is situated on the banks of the Raritan River in Middlesex County, New Jersey, 31 miles southeast of New York City and 20 miles south of Newark International Airport. New Brunswick is home to Johnson and Johnson, the world’s largest health care products manufacturer established in 1885. New Brunswick has many historical sites, such as the State Theatre, Joyce Kilmer House, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, NJ Agricultural museum, Crossroads Theatre, George Street Playhouse, Rutgers Gardens, and more. We at Rutgers University School of Social Work, and I personally, look forward to welcoming you to New Brunswick, working to make your annual convention a success, and ensuring that your stay in New Brunswick is enjoyable. Sincerely, Chien-Chung Huang Director, Huamin Research Center Associate Professor School of Social Work Rutgers University Conference Meeting Rooms: Rutgers University, New Brunswick campus, which is a walking distance from hotel. Conference Hotel: Heldrich Hotel 10 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 Telephone : (732) -729-4670 http://www.theheldrich.com/default.asp Room rate: 109, plus tax = $125. -

Transit Access to NJ COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES As of 1-13-21 1 Megasites Are in BOLD Facility Name Facility Address Phone

Transit Access to NJ COVID-19 VACCINATION SITES as of 1-13-21 1 Sources: NJ COVID-19 Information Hub, nj.com, njtransit.com, google maps, NJTPA CHSTP Visualization Tool (created by Cross County Connection), Greater Mercer TMA, Hunterdon County Transit Guide, Middlesex County Transit Guide, Ocean County Online Bus Tracker App & Schedules, Ridewise of Somerset, Warren County Route 57 Shuttle Schedules Megasites are in BOLD ** site is over 1 mile from transit stop Facility Name Facility Address Phone Bus Other Transit ATLANTIC Atlantic County Health Atlantic Cape Community College (609) 645-5933 NJT Bus # 502 Department 5100 Black Horse Pike NJT Bus # 552 Mays Landing, NJ 08330 Atlanticare Health Services 1401 Atlantic Avenue, Suite 2800 (609) 572-6040 NJT Bus # 565 FQHC Atlantic City, NJ 08401 MediLink RxCare 44 South White Horse Pike N/A NJT Bus # 554 Hammonton, LLC Hammonton, NJ 08037 ShopRite Pharmacy #633 616 White Horse Pike (609) 646-0444 NJT Bus # 508 Absecon, NJ 08201 NJT Bus # 554 Atlantic City Convention 1 Convention Boulevard N/A NJT Bus # 319 Atlantic City Rail Center Megasite Atlantic City, NJ 08401 NJT Bus # 501 Station NJT Bus # 502 NJT Bus # 504 Jitneys: NJT Bus # 505 AC1 NJT Bus # 507 AC3 NJT Bus # 508 AC4B NJT Bus # 509 NJT Bus # 551 NJT Bus # 552 NJT Bus # 553 NJT Bus # 554 NJT Bus # 559 2 Facility Name Facility Address Phone Bus Other Transit BERGEN Bergen New Bridge Medical 230 East Ridgewood Avenue N/A NJT Bus # 168 Center Annex Alternate Care Paramus, NJ 07652 NJT Bus # 752 Facility NJT Bus # 758 NJT Bus # 762 NJT -

Northeast Corridor Capital Investment Plan Fiscal Years 2020-2024

Northeast Corridor Capital Investment Plan Fiscal Years 2020-2024 March 2019 Congress established the Northeast Corridor Commission to develop coordinated strategies for improving the Northeast’s core rail network in recognition of the inherent challenges of planning, financing, and implementing major infrastructure improvements that cross multiple jurisdictions. The expectation is that by coming together to take collective responsibility for the NEC, these disparate stakeholders will achieve a level of success that far exceeds the potential reach of any individual organization. The Commission is governed by a board comprised of one member from each of the NEC states (Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland) and the District of Columbia; four members from Amtrak; and five members from the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). The Commission also includes non- voting representatives from freight railroads, states with connecting corridors and several commuter operators in the Region. Contents Letter from the Co-Chair 1 Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 5 2. FY20-24 Capital Investment Plan 7 Project Information Appendix 19 A. Capital Renewal of Basic Infrastructure 20 Figure A-1. Amtrak FY20-24 Baseline Capital Charge Program 22 Figure A-2. Metro-North Railroad FY20-24 Baseline Capital Charge Program 23 Figure A-3. Connecticut DOT FY20-24 Baseline Capital Charge Program 24 Figure A-4. MBTA FY20-24 Baseline Capital Charge Program 26 B. Special Projects 28 Figure B-1. Summary of special project funding requirements 29 Figure B-2. Special project listing by coordinating agency 34 Letter from the Co-Chair The Northeast Corridor is the nation’s busiest and most complex passenger railroad. -

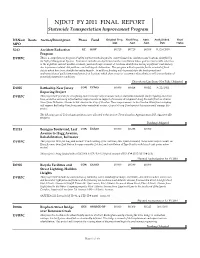

NJ FY11 Obligations for Highway and Transit Projects

NJDOT FY 2011 FINAL REPORT Statewide Transportation Improvement Program DBNum Route Section/Description Phase Fund Original Prog. Final Prog. Auth. Auth./Sched. Final MPO Amt. Amt. Amt. Date Status X242 Accident Reduction EC HSIP $0.720 $0.720 $0.310 11/29/2010 Program DVRPC This is a comprehensive program of safety improvements designed to counter hazardous conditions and locations identified by the Safety Management System. Treatments include raised pavement marker installation whose goal is a measurable reduction in the nighttime and wet weather accidents, pavement improvements at locations identified as having significant crash history due to pavement related skid problems, and utility pole delineation. This program will also provide for the removal of fixed objects which have been identified as safety hazards. In addition, funding will be provided for the development and implementation of quick-turnaround projects at locations which show excessive occurrence of accidents as well as remediation of potentially hazardous conditions. Drawdown Line Item - Not Fully Obligated D1005 Battleship New Jersey CON DEMO $0.000 $0.414 $0.412 9/22/2011 Repaving Project DVRPC This project will provide for resurfacing and streetscape improvements such as sidewalks, handicap ramps, lighting and street trees, as well as necessary infrastructure improvements in support of economic development along the waterfront on Clinton Street from Delwawre Avenue to 3rd street in the City of Camden. These improvements to the Camden Waterfront entryway will support Battleship New Jersey and other waterfront venues. Cooper's Ferry Development Association will manage this project. The following special Federal appropriations were allocated to this project: FY08 Omnibus Appropriations Bill, $422,100 (ID #NJ285). -

Along the Rails

® REAL ESTATE & CONSTRUCTION REPORT Along the Rails DEVELOPERS FLOCK TO TRANSIT STATIONS Ambitious projects mix residential & commercial Their targets: commuters, empty-nesters, millennials REAL ESTATE & CONSTRUCTION REPORT ® Table of contents 220 DAVIDSON AVE., SUITE 302 SOMERSET, NJ 08873 PHONE (732) 246-7677 Letter to readers .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 FAX (732) 846-0421 PUBLISHER Ken Kiczales [email protected] Whistle stops: GENERAL MANAGER AnnMarie Karczmit [email protected] The Link at Aberdeen .......................................................................................................................................................................................4 ADVERTISING SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE The Grande at Metropark .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Penelope Spencer [email protected] ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Susan Alexander [email protected] The Hub@New Brunswick ......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Kirsten Rasky [email protected] Damon Riccio [email protected] Ridin’ the rails with Russo Development ..............................................................................................................