Operating Passenger Railroad Stations in New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

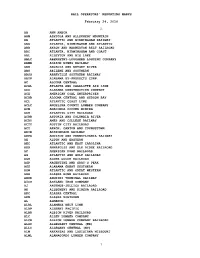

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Rio Grande Station Cape May County, NJ Name of Property County and State 5

NPS Form 10-900 JOYf* 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) !EO 7 RECE!\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n m National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ii:-:r " HONAL PARK" -TIO.N OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name R'Q Grande Station____________________________________ other names/site number Historic Cold Spring Village Station______________________ 2. Location street & number 720 Route 9 D not for publication city or town Lower Township D vicinity state New Jersey_______ code NJ county Cape May_______ code 009 zip code J5§204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Q nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D doss not meet the National Register criteria. -

No Action Alternative Report

No Action Alternative Report April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. NEC FUTURE Background ............................................................................................................................ 2 3. Approach to No Action Alternative.............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 METHODOLOGY FOR SELECTING NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE PROJECTS .................................................................................... 4 3.2 DISINVESTMENT SCENARIO ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. No Action Alternative ................................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 TRAIN SERVICE ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 4.2 NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE RAIL PROJECTS ............................................................................................................................... 9 4.2.1 Funded Projects or Projects with Approved Funding Plans (Category 1) ............................................................. 9 4.2.2 Funded or Unfunded Mandates (Category 2) ....................................................................................................... -

SIAN Vol. 46 No. 1

Volume 46 Winter 2017 Number 1 From Handcraft to High-Tech IA in Northeast Wisconsin ortheast Wisconsin’s Lower Fox River Valley offered The National Railroad Museum in Green Bay was a memorable Fall Tour for the 50 or so SIA mem- host to our Thursday-evening opening reception. We were bers who met up for a three-day event that began greeted by a nice spread of food and drink laid out buffet Non Oct. 27. The Lower Fox River flows northeast- style, but the centers of attention were beautifully restored ward from Lake Winnebago through Appleton, Kaukauna, locomotives and cars, including Union Pacific No. 4017, and De Pere to Green Bay. Our itinerary took us up and down a 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy,” which towered over the reception the valley several times, and extended somewhat beyond area. There was time to take in the exhibits, one of which, the valley along the west shore of Lake Michigan. Process Pullman Porters: From Service to Civil Rights, featured a fully tours ranged from a traditional handcraft cheese factory to furnished 1920s Pullman sleeper. SIA President Maryellen a high-tech maker of computer circuit boards. A series of Russo and SIA Events Coordinator Julie Blair welcomed museums and historic sites featured railroads, canals, automo- participants and explained logistics for the next several biles, papermaking, hydroelectric power, and wood type and days of tours. Julie introduced Candice Mortara, SIA’s local printing machinery. Accommodations were in two boutique coordinator and a member of Friends of the Fox, a not-for- hotels, one with an Irish theme (the St. -

West Orange, NJ

■ ONE OF THE BETTENBETTER 268 Main St., Orange, N* J* Tel. Orange 3-1020 ------- BRANCH: 144 SOUTH HARRISON ST. EAST ORANGE S Drug Stores TELEPHONE ORANGE 5-743© 0 A HIGHLY PERSONALIZED SERVICE SB EMBRACING EVERY BANKING FACILITY ORANGE FIRSf NATIONAL BANK 0 282 Main St., Just East off Day St. ORANGE Bfl. RAYMOND RILEY, President Member of Federal Reserve System and Federal Deposit Insuranee Corp. I I A REAL ESTATE FIRM THAT IS AN INSTITUTIONS.*- o « = Frank H. Taylor & Son, Inc. ...... — NOTE FIRST NAME REALTORS 57 Years INSURANCE MEMBERS AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF REAL ESTATE APPRAISERS Telephone Orange 3-8100 620 Main St., Brick Church Section East Orange, New Jersey 10 ..... .... ... .............................. ... ...... ...................... —” C 9 First National Bank O WEST ORANGE, NEW JERSEY I This Bank offers complete facilities for all branches of Banking and solicits your business, personaf] and savings accounts TRUST DEPARTMENT MEMBER FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATION THE HALF DIME SAVINGS BANK INCORPORATED MARCH 17, 1870 356-358 Main SL, cor. Lackawanna Plaza Orange, New Jersey CO SAVESSTART TO-DAY for any PURPOSE you will but— U s sa t m | p AT THIS BANK— fe WILBUR MUNN, President HARVEY M. ROBERTS, Vice-Pres. and Cashier GEORGE H. WERNER, Vice-Pres. EDWIN H. VOLCKMANN, Asst. Cashier m SecondlNational Balk O Q i 308 Main Street, Metropolitan Building O range, N . J . I I Zlz 1 SAVINGS DEPARTMENT TRUST DEPARTMENT | M | | p Safe Deposit Boxes and Storage for Silverware I lO H l MEMBER FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE CORPORATiP| & 53 Academy Street I gps?5l F5NEST DRESS NEWARK, U SUIT RENTAL Tel. -

Guide to the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records

Guide to the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records NMAH.AC.1074 Alison Oswald 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Historical........................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Business Records, 1903-1966.................................................................. 5 Series 2: Drawings, 1878-1971................................................................................ 6 Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Records NMAH.AC.1074 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: -

Auction Database 0206 IN

Toy Train Auction Lot Descriptions June 14, 2014 2001 Lionel postwar 2460 and 6460 black Bucyrus Erie crane cars. The 2460 is C7-8 and the 6460 is C7. 2002 Lionel postwar two 6560 Bucyrus Erie crane cars, one with red cab and one with a gray cab. Also included is a 6660 boom car with a detached hook that is included. All cars are C6. 2003 Lionel postwar 2332 dark green Pennsylvania GG1 electric diesel with five stripes. The stripes and lettering are faded. The GG1 is C6. 2004 Lionel postwar 2560 crane car with cream cab, red roof and black boom, C6. 2005 Lionel postwar Five-Star Frontier Special outfit no. 2528WS including; 1872 General steam loco, 1872T W.& A.R.R. tender, 1877 horse car with six horses, 1876 baggage car and a 1875W illuminated passenger car with whistle. The ornamental whistle on the engine is broken and the piping detail on the hand rails is broken. Engine is C6. Rest of set is C7. 2006 Lionel postwar freight cars including; X2454 orange Pennsylvania boxcar with original cardboard insert, X2758 Tuscan Pennsylvania boxcar and a 2457 red Pennsylvania caboose. The X2454 is C5. The other two cars are C7. The 2478 is in a reproduction box. The other two cars are in OBs. The OBs show some wear. 2007 Lionel postwar 726RR Berkshire steam loco and a 2046W tender, circa 1952, C7. The tender is in a worn OB. 2008 Lionel postwar X6454 Tuscan Pennsylvania boxcar and a 6420 gray searchlight wrecking car with original cardboard insert both in OBs. -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

Imnial and Ferry in Hoboken ^- Imlllilpii^Llll STREET and NUMBER

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR £ TATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Jersey c :OUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Hudson INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE N , (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) u^L 24197: \ &S::S::¥:::M:::!%K:^ ;:;x;:;:¥:;:::;::::x;x:x;:::x:;:::;:::;:;X:::::::: :: x : XxXx ;Xx : ; XvXx • ': ':•/.••:] • x xxx; XxXxIxoxxx;:; COMMON: Erie-Lackawanna Railroad -Terminal at Hoboken AND/OR HISTORIC: , . Delaware, Lackawanna, & Western Railroad Teimnial and Ferry in Hoboken ^- imlllilpii^llll STREET AND NUMBER: . ^ . • Baflit-af- Hudson River, 'at the foot of Hudson Place -\ CITY OR TOWN: Hoboken STATE . CODE COUNTY: CODE New Jersey 3U Hudson ol^ STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) . TO THE PUBLIC |7J District 0? Building D Public • Public Acquisition: S Occupied Yes: i —i ii .1 Z 1 Restricted Q Site Q Structure C Private Q In Process | _| Unoccupied ^^ i —. _ . [~] Unrestricted CD Object ' D Both 3f7J Being Considered |_J Preservation, work in progress > — > PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) . • [ I Agricultural [~l Government [~] Park QU TfBTfsQrtanoB^. yi Comments M Commercial Q Industrial [~] Private Residence H L~) Educational LJ Mi• itary• * | | Religious /*V/ v^ /v^x^. (71 Entertainment 1 1 Museum ( | Scientific J^W7 ^^yi/ra^1^^ f «— i ..._.... •/»«. *-/ L JT \ ^^^M^Sfiils^Siliillft^P u OWNER'S NAME: |^1 Afj ^ W7J j—J ^ 0) • TREET AND NUMBER! \fK ^£V? O* / CITY OR TOWN: STATE: ^^/JJg^ V>^ CODE CO Cleveland Ohio 39 ^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: Hudson County ftourthouse • . - STREET AND NUMBER) ICO o p CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Jersey City New Jersey 3k TITLE OF SURVEY: ENTR MAW Jersey Historic Sites Inventory (lk80.9) Tl O NUMBERY DATE OF SURVEY: 1972 D Federal [~^ State [71 County [71 Local 73 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Z-o ilnrfh. -

New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT). 2011. New

New Jersey Statewide Transportation Improvement Program Fiscal Years 2012 - 2021 Governor Chris Christie Lt. Governor Kim Guadagno Commissioner James S. Simpson October1, 2011 Table of Contents Section IA Introduction Section IB Financial Tables Section II NJDOT Project Descriptions Section III NJ TRANSIT Project Descriptions Section IV Authorities, Project Descriptions Section V Glossary Appendix A FY 2011 Major Project Status Appendix B FY 2012-13 Study & Development Program SECTION IA INTRODUCTION Introduction a. Overview This document is the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program for the State of New Jersey for federal fiscal years 2012 (beginning October 1, 2011) through 2021. The Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) serves two purposes. First, it presents a comprehensive, one-volume guide to major transportation improvements planned in the State of New Jersey. The STIP is a valuable reference for implementing agencies (such as the New Jersey Department of Transportation and the New Jersey Transit Corporation) and all those interested in transportation issues in this state. Second, it serves as the reference document required under federal regulations (23 CFR 450.216) for use by the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Administration in approving the expenditure of federal funds for transportation projects in New Jersey. Federal legislation requires that each state develop one multimodal STIP for all areas of the state. In New Jersey, the STIP consists of a listing of statewide line items and programs, as well as the regional Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) projects, all of which were developed by the three Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs). The TIPs contain local and state highway projects, statewide line items and programs, as well as public transit and authority sponsored projects. -

NEW JERSEY TRANSIT RAILROAD STATION SURVEY I, IDENTIFICATION 2. EVALUATION

'"*""' Jl|N 2 2 1984 1 N.J. Office of Cultural and Environmental Services, 109 W. State Street, Trenton, N.J. 08625 609-292-2023 Prepared by Heritage Studies, Inc. Princeton, N.J. 08540 609-452-1754 RR O7OS- Survey # 4-1 NEW JERSEY TRANSIT RAILROAD STATION SURVEY i, IDENTIFICATION ^ A. Name: Common Ampere ^ <•''"•"• Line: Hoboken Division, Montclair Historic Branch (DL&W) B. Address or, location: E of Ampere ^ /^ r-»r e piaza IfltWiitney Plac€ ^ County: Essex ^ East Orange, NJ ' Municipality: City of East Orange Block & lot: C. Owner's name: NJ Transit Address: Newark, NJ D. Location of legal description: Office of the County Clerk, Essex Co. C. H-. Newark, NJ I. Representation in existing surveys: (give number, category, etc., as appropriate) HABS _____ HAER ____ELRR Improvement___NY&LB Improvement ____ PI a infield Corridor _____NR(name, if HP).__________________ NJSR (name, if HP)_____________________ NJHSI (#) ______________ Northeast Corridor Local ______________________________(date_____________ Modernization Study: site plan X floor plan_X_ _aerial photo other views x photos of NR quality? x_______ 2. EVALUATION A. Determination of eligibility: SHPO comment? __________(date____) NR det.? (date ) B. Potentially eligible for NR: yes_j(_possible __ no __ individual thematic C. Survey Evaluation: 120/110 points 115 -2 RR O7OS- FACILITY NAME: Ampere Survey #4-1 3. DESCRIPTION-COMPLEX IN GENERAL Describe the entire railroad complex at this site; mention all buildings and structures, with notation of which are not historic. Check items which apply and discuss in narrative: _Moved buildings (original location, date of and reason for move) _Any non-railroad uses in complex (military recruiting, etc.) _Any unusual railroad building types, such as crew quarters, etc.