Swaziland's First State of Environment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UJOE Vol. 3 No 2 (DECEMBER, 2020) the IMPACT OF

UJOE Vol. 3 No 2 (DECEMBER, 2020) THE IMPACT OF NTFONJENI RURAL EDUCATION CENTRE’S ELECTRICAL INSTALLATION PROGRAMME ON PROMOTION OF SELF-RELIANCE AMONG GRADUATES Zandile Tsabedze* University of Eswatini Eswatini Nomazulu Ngozwana University of Eswatini . Eswatini David Jele University of Eswatini Eswatini ABSTRACT This study assessed the impact of Ntfonjeni Rural Education Centre’s (REC) electrical installation programme on promotion of self-reliance among out-of-school youth and adults in Eswatini, Hhohho Region. The objectives of the study were to: establish whether the electrical installation programme objectives were met, determine the electrical installation programme activities undertaken by graduates; and determine the engagement with learning by graduates in promoting self-reliance as a result of the electrical installation programme offered at Ntfonjeni REC. This was a small-scale study that used the evaluation research design with qualitative research methods. Data were collected using interviews, observation, and documents. Participants were graduates from the electrical installation programme, electrical installation instructor and community members that were chosen using convenient, purposive, and snowballing sampling techniques, respectively. Seventeen participants were individually interviewed using structured interviews. Data were analyzed qualitatively through thematic analysis. The findings revealed that the goal of the electrical installation programme of promoting self-reliance among its graduates was partially met. -

Impact Analysis of Smallholder Irrigation Schemes on Household Poverty Reduction in Swaziland: the Case of Ntfonjeni and Ngwempisi Rural Development Areas

IMPACT ANALYSIS OF SMALLHOLDER IRRIGATION SCHEMES ON HOUSEHOLD POVERTY REDUCTION IN SWAZILAND: THE CASE OF NTFONJENI AND NGWEMPISI RURAL DEVELOPMENT AREAS SITHOLE NOK’PHIWA LAMIE A THESES SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE REQUIREMENT OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMICS OF EGERTON UNIVERSITY EGERTON UNIVERSITY NOVEMBER, 2014 DECLARATION AND APPROVAL 1. Declaration This thesis is my original work and has not been submitted for an award of any degree in any other University. Sithole Nok’phiwa Lamie KM17/3372/12 __________ ______________ Signature Date 2. Approval This thesis has been submitted with our approval as Supervisors. Professor J.K. Lagat, PhD Associate Professor of Agricultural Economics Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness Management, Egerton University, Kenya __________________ __________________ Signature Date Professor M. B. Masuku, PhD Head of Department, Agricultural Economics and Management, University of Swaziland _______________ ___________________ Signature Date i COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2014 Sithole Nok’phiwa Lamie No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored, in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, and recording without prior written permission of the author or Egerton University on that behalf. All rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my dear mom Mrs. T.E. Sithole for her hard work, prayer, the role of a model and an inspiring Mother. My beloved Father, my brothers and sisters. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I give my sincere gratitude to Egerton University for allowing me to pursue Master of Science degree in Agricultural and Applied Economics, the German Academic Exchange Service – Deutscher Akadamischer Austauscdienst (DAAD) for providing me with a scholarship through the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) / Collaborative Master of Science in Agricultural and Applied Economics (CMAAE) Programme. -

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary

Swaziland Government Gazette Extraordinary VOL. XLVI] MBABANE, Friday, MAY 16th 2008 [No. 67 CONTENTS No. Page PART C - LEGAL NOTICE 104. Registration Centres For the 2008 General Elections................................................... SI PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY 442 GENERAL NOTICE NO. 25 OF 2008 VOTERS REGISTRATION ORDER, 1992 (King’s Order in Council No.3 of 1992) REGISTRATION CENTRES FOR THE 2008 GENERAL ELECTIONS (Under Section 5(4)) Short title and commencement (1) This notice shall be cited as the Registration Centres Notice, 2008. (2) This general notice shall come into force on the date of publication in the Gazette. Registration centres for the 2008general elections It is notified for general information that the registration of all eligible voters for the 2008 general elections shall be held at Imiphakatsi (chiefdoms) and at the registration centres that have been listed in this notice; REGISTRATION CENTRES HHOHHO REGION CODE CODE CODE CHIEFDOM / POLLING Sub polling REGION INKHUNDLA STATION station 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 01 Dlangeni 01 HHOHHO 01 HHUKWINI 02 Lamgabhi 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 01 Elangeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 02 Ezabeni 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 03 Ezulwini 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 04 Lobamba 01 HHOHHO 02 LOBAMBA 05 Nkhanini 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 01 Buhlebuyeza 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 02 KaGuquka 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 03 Kuphakameni/ Dvokolwako 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 04 Mzaceni 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 05 Nyonyane / KaMaguga 01 HHOHHO 03 MADLANGEMPISI 06 Zandondo 01 HHOHHO 04 MAPHALALENI 01 Edlozini 443 -

In the High Court of Swaziland

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SWAZILAND HELD AT MBABANE CASE NO. 856/15 and CASE NO. 782/15 In the matter between: THOKO DLAMINI PLAINTIFF and THE PRINCIPAL SECRETARY MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND TECHNOLOGY 1ST DEFENDANT ATTORNEY GENERAL 2ND DEFENDANT CASE NO. 856/2015 LOMGCIBELO DLAMINI PLAINTIFF AND THE PRINCIPAL SECRETARY MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND TECHNOLOGY 1ST DEFENDANT ATTORNEY GENERAL 2ND DEFENDANT CASE NO. 782/2015 Neutral Citation : Thoko Dlamini and Lomgcibelo Dlamini vs Principal Secretary, Ministry of Information and technology (856/15 & 782/15) [2018] SZHC 223 (26 FEBRUARY 2019) Coram : MABUZA – PJ Heard : 2017, 2018. Delivered : 26 FEBRUARY 2019 1 SUMMARY Civil Law – Evictions and Demolitions - Without compensation – The two Plaintiffs who are siblings seek damages from the Government of Eswatini - Suffered as a result of their eviction from their ancestral homes which were subsequently demolished - Plaintiffs were not compensated. JUDGMENT MABUZA -PJ [1] In this matter the Government of Eswatini through the Ministry of Information, Communication Technology (ICT) initiated a project for the construction of a Royal Technology Park (the Technology Park) at Nokwane in the Manzini District. [2] The Technology Park was to be constructed on certain immovable property (the Farm) at Nokwane owned by Ingwenyama in Trust for the Swazi Nation under Deed of Donation Transfer No. 176/2005 executed on the 15th March 2005 (Exhibit D (A)). [3] The Farm is described therein as: “CERTAIN : Portion 26 (a portion of Portion 1) of Farm No. 692 situate in the Manzini District, Swaziland. 2 MEASURING : 102, 2491 (One Zero Two Comma Two four nine one) Hectares. -

The Kingdom of Swaziland

THE KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND MASTERPLAN TOWARDS THE ELIMINATION OF NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES - 2015- 2020 Foreword Acknowledgements Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 1 LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................. 5 PART 1: SITUATION ANALYSIS ....................................................................................... 10 1.1 Country profile ......................................................................................................... 10 1.1.1 Geographical characteristics ............................................................................... 10 1.1 .2 PHYSICAL FEATURES AND CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ....................................... 11 1.1.3. ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURES, DEMOGRAPHY AND COMMUNITY STRUCTURES ................................................................................................................... 12 1.3.2 Population ............................................................................................................. 13 Health Information System ........................................................................................... 25 Health workforce ........................................................................................................... 26 Medical products .......................................................................................................... -

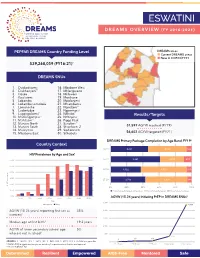

DREAMS Fact Sheet ESWATINI

ESWATINI DREAMS OVERVIEW (fy 2016-2021) PEPFAR DREAMS Country Funding Level DREAMS areas Current DREAMS areas New in COP20/FY21 $39,268,059 (FY16-21)* DREAMS SNUs 1. Dvokodvweni 16. Mbabane West 2. Ekukhanyeni** 17. Mhlangatane 3. Hosea 18. Mkhiweni 4. Kwaluseni 19. Motshane 5. Lobamba 20. Mpolonjeni 6. Lobamba Lomdzala 21. Mtsambama 7. Lomahasha 22. Ngudzeni** 8. Ludzeludze 23. Ngwempisi 9. Lugongolweni** 24. Nkhaba** Results/Targets 10. Madlangampisi** 25. Ntfonjeni 11. Mafutseni** 26. Piggs Peak ** 12. Manzini North 27. Sandleni 5 13. Manzini South 28. Shiselweni 2 31,597 AGYW reached (FY19) 14. Maseyisini 29. Siphofaneni * 15. Mbabane East 30. Sithobela 56,602 AGYW targeted (FY21) DREAMS Primary Package Completion by Age Band, FY195 Country Context 10-14 4,031 4,044 566 HIV Prevalence by Age and Sex1 15-19 60.0% 5,281 2,507 857 50.0% 20-24 3,022 4,515 510 40.0% 30.0% 25-29 2,712 3,208 344 20.0% HIV Prevalence HIV 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 10.0% Primary Package Completed and Secondary Primary Package Completed Primary Package Incomplete 0.0% 5 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 AGYW (15-24 years) Initiating PrEP in DREAMS SNUs Age 5,000 Female Male 4,755 AGYW (18-24 years) reporting first sex as 35% 4,000 coerced2 3,000 Median age at first birth3 19.2 years 2,000 AGYW of lower secondary school age 5% 4 who are not in school 1,000 704 1 99 108 SOURCES: 1. -

Press Release the Elections and Boundaries Commission Is Pleased to Report and Announce That the Primary Elections Conducted On

Press Release The Elections and Boundaries Commission is pleased to report and announce that the primary elections conducted on the 5th of June 2021 were a tremendous success. These elections are part of the by election of Members of Parliament for Shiselweni 1 and Lamgabhi Tinkhundla, Indvuna Yenkhundla of Matsanjeni South Inkhundla and Bucopho for Lomshiyo and Lomfa Imphakatsi at Ntfonjeni Inkhundlla. The commission is grateful to the electorate for being part of this exercise amidst difficult conditions such as the Covid 19 scourge and freezing weather. It is pleasing to note that by elections were held under the watchful eyes of stakeholders such as the media and internal observer missions. Candidates displayed professional conduct before, during and after the elections which gives credibility to our electoral process. The commission is very much alive to the new normal due to Covid 19 and has partnered with various institutions to ensure the safety of our polling staff and the electorate. It is humbling to note that no casualties have been recorded in all our process. Much appreciation goes the Ministry of Health, the electorate and the National Disaster Management Agency for trusting and supporting the commission in such a sensitive exercise. The primary election results are attached. The commission takes this opportunity to congratulate the successful candidates of the primary elections especially the Bucopho for Lomshiyo and Lomfa who have duly taken office. The other candidates for secondary elections are encouraged to continue with the professional conduct during processes such as the campaigns which have just started. The electorate will be continuously informed through all forms of media on the electoral processes towards the final polling day on the 3rd of July 2021. -

Original Research Article Open Access

Available online at http://www.journalijdr.com ISSN: 2230-9926 International Journal of Development Research Vol. 09, Issue, 06, pp. 28352-28357, June, 2019 REVIEW ARTICLE ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS DETERMINATION OF DDT AND ITS METABOLITE IN MARULA PRODUCTS IN ESWATINI USING A MOLECULAR IMPRINTED POLYMER *Sithole Nothando Beautiness, Thwala Justice Mandla and Bwembya Gabriel Chewe University of Eswatini, Department of Chemistry, Kwaluseni, Eswatini ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) is an effective organochlorine pesticide which is used in Received 25th March, 2019 Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) in Eswatini yet it is toxic, susceptible to long range Received in revised form environmental transport and bio-accumulate in fatty tissues. The main objective was to quantify 22nd April, 2019 the amount of DDT and its metabolites (DDE and DDD) in Marula brew and kernels. The Accepted 21st May, 2019 samples were pre-extracted with acetonitrile, extracted using a periodic mesoporousorganosilica th Published online 30 June, 2019 molecular imprinted polymer (PMO-MIP) with acetone in cyclohexane and then analyzed with GC/ECD. DDT was detectedin 88% of the samples with the highest concentrations at 0.903 ppm Key Words: in brew and 148.686 mg/kg from the kernels. DDD was detected in 86% of the Marula brew DDT, marula products, samples with the highest concentration at 0.483 ppm and 68.219 mg/kg from the kernels. mesoporous, organosilica, imprinted, polymer However, DDE was found in lower concentrations of 0.138 ppm and 30.132 mg/kg from the brew and residual. and kernels respectively. The study concluded that people and animals are at risk of DDT residual accumulation as 98% of the samples collected had the analytes detected at level above the WHO safety limit of 0.05 ppm. -

Proceedings of the National Seminar on Institutions Working on Gender, Biodiversity and Local Knowledge Systems in Swaziland

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL SEMINAR ON INSTITUTIONS WORKING ON GENDER, BIODIVERSITY AND LOCAL KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS IN SWAZILAND Edited by Phonius M. Dlamini Department of Agricultural Economics and Management University of Swaziland. E-Mail : [email protected] and Bruce R. T. Vilane Department of Land Use and Mechanization University of Swaziland. E-Mail : [email protected] April, 2001 LinKS PROJECT WORKING DOCUMENT N0. 3 HOSTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SWAZILAND – FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE [CONFERENCE ROOM] : 16 – 17 MARCH 2001. COPYRIGHT This document is a collective sharing of ideas and experiences and thus copyright does not reside either with the editors, anyone of the contributors or their parent institutions. However, usage of any material or reproduction, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, as a matter of courtesy, acknowledgement of the source should be given. The views expressed are those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Copyright © FAO, 2001. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Copyright ...................................................................................................………………. iii List of Tables .....................................................................................................…………. v Preface.................................................................................................................…………. vi 1.0 KEYNOTE ADDRESS By The Honourable Minister of Tourism, Environment and Communication (Mrs. Stella Lukhele...................…......... 1 2.0 DAY ONE : PAPER PRESENTATIONS……………………………….…… 3 2.1 Gender Papers :…………………………………………………………………….. 3 2.1.1 Gender, Biodiversity and Local Knowledge Systems : Highlights and Submissions of the Seminar Discussions :………………………… 3 2.1.2 Gender and Food Security by Dr. P.E. Zwane :……………………………………. 13 2.2 Biodiversity Papers :.……………………………………………………………… 26 2.2.1 Biodiversity Management in Swaziland by Mr. -

SWAZILAND Vulnerability Assessment Committee Results 2015

SWAZILAND Vulnerability Assessment Committee Results 2015 Regional Socio - Economic Context Population at risk of food and livelihoods insecurity trend Malnutrition Rates (%) 2014/15 Population 1,12 million people Stunting Underweight Wasting Life expectancy 47.8 years 262,000 223,249 28.7 31 Population Growth Rate 1.0% 160,989 201,000 29 115,713 Human Development Index 0.148 (2013) 88,511 25.5 Adult Literacy 87.8% (2012) Employment Rate 71.9% (2014) Average GDP Growth 2.3% (2013) 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 Under 5 Mortality Rate 67 per 1,000 live births May 2015 to April 2016 Projected Livelihood Outcomes 9.6 Inflation 5.70% (2015, CSO) 5.8 HIV and AIDS 26.0% (2009) Timphisini Proportion of Children (%) 5.4 5.8 Ntfonjeni Mayiwane 2.5 2 1.2 0.8 Objectives of Assessment 2014/15 Mhlangatane Pigg's Peak 2000 2007 2010 2014 • To assess the status of livelihoods and vulnerability in rural households and provide timely Ndzingeni information for programming and decision making. 201,000 Lomahasha population at risk of food • To understand the different capabilities (assets) of households to cope with crises such as Mandlangempisi Mhlume Key Recommendations and livelihoods Nkhaba droughts, floods, economic fluctuations, plant or animal pests and diseases. • Crop diversification (not only maize) especially in the Lubombo region and production of insecurity Maphalaleni • Use the Household Economy Approach to get the numbers of people food insecure for the drought resistant crops in this region. consumption period 2015-2016. Mbabane Mkhiweni Hlane • Use of the existing irrigation infrastructure for sugar cane plantations. -

Annex 1: AIR CONDITIONER REQUIREMENTS

Annex 1: AIR CONDITIONER REQUIREMENTS Facility Geo coordinates Telephone Region Facility Name Size of room Size of room Dispensary Storeroom Number Point of Contact Non-Functional Not Available Non-Functional Not Available Longitude Lattitude Hhohho South Hhukwini Clinic √ 5mx4m 5mx4m 31.36056 -25.86526 2437 1516 Hhohho South Motshane Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.26676 -26.07466 2442 4289 Hhohho South Maphalaleni Clinic √ 5mx4m 5mx4m 7651 7393 Sifundo Zwane Hhohho South Sigangeni Clinic √ 5mx4m 5mx4m 31.1315 -26.31871 2482 9017 Hhohho South Lobamba Clinic 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.50814 -25.9018 2416 1047 Hhohho North Ntfonjeni Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.17391 -26.57164 2431 7295 Hhohho North Horo Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.32407 -26.97256 2431 5706 Hhohho North Bulandzeni Clinic 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.31638 -26.50589 2383 8036 Hhohho North Ngowane Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.19903 -27.11323 7651 7393 Sifundo Zwane Hhohho North Vusweni Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 7651 7393 Sifundo Zwane Shiselweni Nhletjeni Clinic √ 5mx4m 5mx4m 31.145089 -26.137841 2207 9031 Shiselweni Nkwene Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.892271 -26.834293 2207 8930 Shiselweni Kaphunga Government Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 30.884836 -26.578047 2207 9135 Shiselweni Mhlosheni Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.874413 -26.583063 7617 8701 Norman Malinga Shiselweni KaMfishane Clinic 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.228672 -26.771617 2207 8912 Shiselweni New Haven Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.434618 -26.004037 2207 9038 Shiselweni Ntshanini Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m 31.344746 -25.830608 2207 8929 Shiselweni Zombodze Clinic √ 5mx4m √ 5mx4m -

2019 ESWATINI VAC REPORT.Pdf

KINGDOM OF ESWATINI ANNUAL VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT & ANALYSIS REPORT 2019 July 2019 ___________________________________________________________________________ A. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The 2019 Annual Vulnerability and Livelihood Assessment covered all key sectors including; agriculture, health, nutrition and education in an effort to understand household vulnerability status in Eswatini. This multi-sectoral approach required that the Eswatini VAC team collaborates with Government departments, non-state actors and traditional structures for its success. On behalf of the Eswatini Government, I would like to recognise the Government support throughout the annual assessment process. I also want to extend my sincere appreciation for the significant financial and logistical support contributed by Government cooperating partners, World Vision Eswatini, WFP and FAO through SADC Regional Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis (SADC RVAA) Programme. Sincere gratitude is due to all the respondents and facilitators in the communities we visited, which these findings will be shared with and hope they will help to shape the development paths in their respective communities. Finally, may I also applaud the Eswatini VAC Core Team and the data collection teams that worked extremely hard to cover vast numbers of households in each region so to ensure representativeness of the 2019 Annual Assessment findings. Khangeziwe Mabuza Principal Secretary- Deputy Prime Minister’s Office ii B. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The context of the Eswatini Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis for the 2019/20 period was guided by the need to provide current food security and livelihoods information to inform policy and programming decisions in the country. Specific areas covered included agriculture, health and nutrition, water and sanitation, and education. The assessment took place at a time when there were a number of macro-economic challenges in the country, however an observable stability in consumer inflation reflected an opportunity for reduced vulnerability thus enhancing household food consumption.