Chemical Modifications of Porous Shape Memory Polymers For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study Programme for the Quality Management of Essential Medicines - Good Manufacturing Practical (GMP) and Inspection

The Study Programme for the Quality Management of Essential Medicines - Good Manufacturing Practical (GMP) and Inspection - Country Reports Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services (JICWELS) Contents 1. Cambodia 1 2. Indonesia 70 3. Malaysia 91 4. Philippines 116 5. Sri Lanka 141 6. Thailand 161 The Study Programme for the Quality Management of Essential Medicines - Good Manufacturing Practical (GMP) and Inspection - Cambodia -1- KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA Nation Religion King Ministry of Health Department of Drugs and Food Country Report The Study Program on Quality Management of Essential Medicines Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and Inspection November 4, 2012 – November 30, 2012 Sponsored by : The Government of Japan Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Department of Drugs and Food Ministry of Health, Cambodia. -2- I- COUNTRY PROFILE -3- A-Geography Cambodia is an agricultural country located in South East Asia which bordering the Gulf of Thailand, between Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos. Its approximate geographical coordinates are 13°N 105°E. Its 2,572 km border is split among Vietnam (1,228 km), Thailand (803 km) and Laos (541 km), as well as 443 km of coastline. Cambodia covers 181,035 square kilometers in the southwestern part of the Indochina, Cambodia lies completely within the tropics; its southernmost points are only slightly more than 10° above the equator. The country is bounded on the north by Thailand and by Laos, on the east and southeast by Vietnam, and on the west by the Gulf of Thailand and by Thailand. It consists of the Tonle Sap Basin and the Mekong Lowlands. To the southeast of this great basin is the Mekong Delta, which extends through Vietnam to the South China Sea. -

Drug-Induced Anaphylaxis in China: a 10 Year Retrospective Analysis of The

Int J Clin Pharm DOI 10.1007/s11096-017-0535-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Drug‑induced anaphylaxis in China: a 10 year retrospective analysis of the Beijing Pharmacovigilance Database Ying Zhao1,2,3 · Shusen Sun4 · Xiaotong Li1,3 · Xiang Ma1 · Huilin Tang5 · Lulu Sun2 · Suodi Zhai1 · Tiansheng Wang1,3,6 Received: 9 May 2017 / Accepted: 19 September 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Background Few studies on the causes of (50.1%), mucocutaneous (47.4%), and gastrointestinal symp- drug-induced anaphylaxis (DIA) in the hospital setting are toms (31.3%). A total of 249 diferent drugs were involved. available. Objective We aimed to use the Beijing Pharma- DIAs were mainly caused by antibiotics (39.3%), traditional covigilance Database (BPD) to identify the causes of DIA Chinese medicines (TCM) (11.9%), radiocontrast agents in Beijing, China. Setting Anaphylactic case reports from (11.9%), and antineoplastic agents (10.3%). Cephalospor- the BPD provided by the Beijing Center for Adverse Drug ins accounted for majority (34.5%) of antibiotic-induced Reaction Monitoring. Method DIA cases collected by the anaphylaxis, followed by fuoroquinolones (29.6%), beta- BPD from January 2004 to December 2014 were adjudi- lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitors (15.4%) and penicillins cated. Cases were analyzed for demographics, causative (7.9%). Blood products and biological agents (3.1%), and drugs and route of administration, and clinical signs and plasma substitutes (2.1%) were also important contributors outcomes. Main outcome measure Drugs implicated in DIAs to DIAs. Conclusion A variety of drug classes were impli- were identifed and the signs and symptoms of the DIA cases cated in DIAs. -

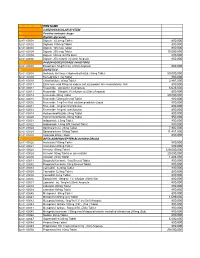

National Code Item Name 1

NATIONAL CODE ITEM NAME 1 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 1A Positive inotropic drugs 1AA Digtalis glycoside 02-01-00001 Digoxin 62.5mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00002 Digitoxin 100mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00003 Digoxin 125 mcg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00004 Digoxin 250 mcg Tablet 15,000,000 02-01-00005 Digoxin 50mcg /ml PG Elixir 800,000 02-01-00006 Digoxin 250 mcg/ml inj (2ml) Ampoule 800,000 1AB PHOSPHODIESTERASE INHIBITORS 02-01-00007 Enoximone 5mg/1ml inj (20ml) Ampoule 800,000 1B DIURETICS 02-01-00008 Amiloride Hcl 5mg + Hydrochlorthiazide 50mg Tablet 50,000,000 02-01-00009 Bumetanide 1 mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00010 Chlorthalidone 50mg Tablet 2,867,000 02-01-00011 Ethacrynic acid 50mg as sodium salt inj (powder for reconstitution) Vial 800,000 02-01-00012 Frusemide 20mg/2ml inj Ampoule 6,625,000 02-01-00013 Frusemide 10mg/ml,I.V.infusion inj (25ml) Ampoule 800,000 02-01-00014 Frusemide 40mg Tablet 20,000,000 02-01-00015 Frusemide 500mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00016 Frusemide 1mg/1ml Oral solution peadiatric Liquid 800,000 02-01-00017 Frusemide 4mg/ml Oral Solution 800,000 02-01-00018 Frusemide 8mg/ml oral Solution 800,000 02-01-00019 Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00020 Hydrochlorothiazide 50mg Tablet 950,000 02-01-00021 Indapamide 2.5mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00022 Indapamide 1.5mg S/R Coated Tablet 800,000 02-01-00023 Spironolactone 25mg Tablet 7,902,000 02-01-00024 Spironolactone 100mg Tablet 11,451,000 02-01-00025 Xipamide 20mg Tablet 800,000 1C BETA-ADRENOCEPTER BLOCKING DRUGS 02-01-00026 Acebutolol 100mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00027 Acebutolol 200mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00028 Atenolol 100mg Tablet 120,000,000 02-01-00029 Atenolol 50mg Tablet or (scored tab) 20,000,000 02-01-00030 Atenolol 25mg Tablet 1,483,000 02-01-00031 Bisoprolol fumarate 5mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00032 Bisoprolol fumarate 10mg Scored Tablet 800,000 02-01-00033 Carvedilol 6.25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00034 Carvedilol 12.5mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00035 Carvedilol 25mg Tablet 800,000 02-01-00036 Esmolol Hcl 10mg/ml I.V. -

Advisory Committee Briefing Document Medical Imaging Drugs Advisory Committee (MIDAC) September 8, 2017

Dotarem® (gadoterate meglumine) Injection – NDA# 204781 Advisory Committee Optimark® (gadoversetamide) Injection - NDAs# 020937, 020975 & 020976 Briefing Document Advisory Committee Briefing Document Medical Imaging Drugs Advisory Committee (MIDAC) September 8, 2017 DOTAREM® (gadoterate meglumine) Injection NDA 204781 Guerbet LLC, 821 Alexander Rd, Princeton, NJ 08540 OPTIMARK® (gadoversetamide) Injection NDAs 020937, 020975 & 020976 Liebel-Flarsheim Company LLC, 1034 Brentwood Blvd., Richmond Heights, MO 63117 ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING MATERIALS AVAILABLE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Information provided within this briefing document is based upon medical and scientific information available to date. ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING MATERIALS AVAILABLE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Page 1 / 168 Dotarem® (gadoterate meglumine) Injection – NDA# 204781 Advisory Committee Optimark® (gadoversetamide) Injection - NDAs# 020937, 020975 & 020976 Briefing Document EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Gadolinium-based contrast agents (GdCAs) are essential for use in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although non-contrast-enhanced MRI may be sufficient for use in some clinical conditions, contrast-enhanced MRI (CE-MRI) using GdCA provides additional vital diagnostic information in a number of diseases. It is widely recognized that CE-MRI increases diagnostic accuracy and confidence, and thus can impact the medical and/or surgical management of patients. Based on the chemical structure of the complexing ligand, GdCA are classified as linear (L-GdCA) or macrocyclic (M-GdCA) and can be ionic or nonionic and those characteristics have a dramatic influence on the stability of the GdCA. Dotarem®, a M-GdCA, was first approved in France in 1989. US-FDA approval was obtained in March 2013 for “intravenous use with MRI of the brain (intracranial), spine and associated tissues in adult and pediatric patients (2 years of age and older) to detect and visualize areas with disruption of the blood brain barrier (BBB) and/or abnormal vascularity”, at the dose of 0.1 mmol/kg BW. -

Optimisation of a New Class of Peptide-Based MRI Contrast Agent

Optimisation of a New Class of Peptide- Based MRI Contrast Agent Sarah Lauren Newton A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PSIBS Doctoral Training Centre School of Chemistry College of Engineering and Physical Sciences The University of Birmingham August 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract To determine the effect rotational correlation time (τR) has on relaxivity, peptides of different lengths were investigated. Extending the length of the peptide had a negligible impact on folding, stability and inner-sphere water coordination. The relaxivity was found to be the same indicating that τR is not the limiting factor in this class of contrast agent. A peptide was designed with the potential to increase secondary sphere water coordination to the peptide exterior. No change in relaxivity was observed, compared to MB1- 2, due secondary sphere H2O being located at too far from the paramagnetic Gd(III). Secondary sphere water coordination was further investigated when a water channel was identified. The channel allows water to come within close proximity of Gd(III), with the potential to increase relaxivity. -

Art. 31 Gadolinium

Annex I List of nationally authorised medicinal products 1 Annex IA – medicinal products containing intravenous gadobenic acid, gadobutrol, gadoteric acid, gadoteridol, gadoxetic acid and intra-articular gadopentetic acid and intra-articular gadoteric acid Member State Marketing Invented name INN + Strength Pharmaceutical form Route of EU/EEA authorisation holder administration Austria Bayer Austria GmbH Magnevist Gadopentetate solution for injection intra-aintra-articular use Dimeglumine 1.876mg/Ml Austria Bayer Austria GmbH Dotagraf Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intravenous use 279.32mg/Ml Austria Bayer Austria GmbH Gadovist Gadobutrol solution for injection intravenous use 604.72mg/Ml Austria Bayer Austria GmbH Primovist Gadoxetic Acid, solution for injection intravenous use Disodium 181.43mg/Ml Austria Bracco Imaging S.p.A. Prohance Gadoteridol solution for injection intravenous use 279.3mg/Ml Austria Guerbet Artirem Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intra-articular use 1.397mg/Ml Austria Guerbet Dotarem Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intravenous use 279.32mg/Ml Austria Sanochemia Cyclolux Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intravenous use Pharmazeutika AG 0.5mmol/Ml Austria Bracco Imaging S.p.A. Multihance Gadobenate solution for injection intravenous use Dimeglumine 529mg/Ml Belgium Agfa Healthcare Imaging Dotagita Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intravenous use Agents GmbH 279.32mg/Ml Belgium Bayer SA NV Dotagraph Gadoteric Acid solution for injection intravenous use 279.32mg/Ml 2 Member State Marketing -

Safety of Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents in Patients with Stage 4 and 5 Chronic Kidney Disease: a Radiologist's Perspective

Kidney360 Publish Ahead of Print, published on January 9, 2020 as doi:10.34067/KID.0000502019 Safety of gadolinium-based contrast agents in patients with stage 4 and 5 chronic kidney disease: a radiologist’s perspective Erik V. Soloff1 and Carolyn L. Wang1 1 University of Washington, Radiology Department Correspondence: Carolyn L. Wang University of Washington Radiology 1959 NE Pacific St Seattle, Washington 98195 [email protected] Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose. Acknowledgments: Author Contributions: Erik Soloff: Conceptualization; Writing - original draft; Writing - review and editing Carolyn Wang: Conceptualization; Writing - original draft; Writing - review and editing Copyright 2020 by American Society of Nephrology. Gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCA) have been used for contrast-enhanced MRI since 1988 with over 450 million intravenous GBCA doses administered worldwide and overall have had an excellent safety record (1, 2). Numerous studies have demonstrated the benefit of GBCAs for a variety of diagnostic indications including improving sensitivity and specificity for malignancy, demyelination, central nervous system malignancy, and infection, among others (3-7). Initially, it was thought that GBCAs would be safer than iodinated contrast media for patients with kidney disease because they are less nephrotoxic at clinically administered doses (8). Although some case reports have linked acute kidney injury (AKI) to GBCA administration, most cases involve patients with advanced renal disease or diabetes and with doses that exceed US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommendations (8). The safety of GBCAs in patients with kidney disease came into question in 2006 when a strong association was found between the use of GBCA in patients with severe kidney disease and the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) (9-11). -

How Does Contrast Media Affect Cardiac Markers And

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 January 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201901.0172.v1 1 Article 2 How Does Contrast Media Affect Cardiac Markers 3 and Coagulation Tests? Experimental Study 4 Mustafa Begenc Tascanov 1,* Ataman Gönel 2 5 1 Department of Cardiology, Harran University, Turkey; [email protected] 6 2 Department of Medical Biochemistry, Harran University, Turkey; [email protected] 7 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +90-555-7860033 8 9 Abstract: 10 Background and objectives: The fact that the results of troponin and Nt-proBNP interfere from biotin 11 caused some commercial firms to update their measurement methods. In particular, the clinical 12 incompatibility of cardiac test results may affect the risk of morbidity and mortality. The aim of this 13 study is to investigate the interference effects of 7 different contrast agents on cardiac markers 14 (Troponin-I, Nt-proBNP, Mass CK-MB, CK, AST, LDH) and coagulation tests (PT, APTT). 15 Materials and Methods: Seven different contrast medias were added into control materials by using 16 interference protocol. Concentration of PT, APTT, CK, AST, LDH, Mass CK-MB, Troponin-I, 17 Nt-proBNP were measured by Sysmex CS-2100, Abbott c16000, Siemens Centaur XP and AFİAS-6 18 analyzer. The amount of deviations from target values were calculated. 19 Results: 7 different contrast medias caused negative interference in troponin levels between 57.43% 20 and 62.87%. It was found that different contrast medias produced false negativity in the pro-BNP 21 test ranging from 6.11% to 96.01%. Enzymes and coagulation tests have been less affected. -

• Synthetic Organic Chemicals 5(F) • for Amendment

SEAC, Gujarat Page 1 of 27 • Synthetic Organic Chemicals 5(f) • For Amendment - Environmental Clearance [EC] 1. Earlier EC letter no. and Date: 2. Basic Information of the Project: i Name & Address of the Project site M/s. Unique Chemicals (Complete details with plot no./Survey (A div of J B Chemicals & no., Landmark etc. ) Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Plot no 5, Phase IV, GIDC, Panoli- 394116, and Dist.: Bharuch, Gujarat. ii Name of the Applicant Mehta Chidambar Bipinchandra iii Address for correspondence M/s. Unique Chemicals (A Div. of J B Chemicals & Pharmaceuticals Ltd) Neelam Centre, B Wing, 4th Floor, Hind Cycle Road, Worli, Mumbai-400030 iv Contact no. and e-mail ID of the Mo. no. : 9998014353 Applicant e-Mail: [email protected] v Aerial distance of nearest Habitat Panoli-5.5 Km (KM) vi Longitude & Latitude of the Project Latitude 21°33’15.62”N, Site: (4 corners of the site) Longitude 73°00’04.81” E. 1st 21°33’20.04”N, 72°59’58.52” E 2nd 21°33’19.79”N, 73°00’05.15” E 3rd 21°33’10.24”N, 73°59’56.27” E 4th 21°33’9.31”N, 73°00’3.55” E vii Category as per the Schedule to the 5 (f) Synthetic Organic Chemicals EIA Notification 2006 i.e. 1(d), 2(b), 5(f) etc. Sub-Category: Pharmaceuticals Ingredients & its Intermediates. viii Applicability of General Conditions NA of EIA Notification 2006: i.e. Ensure that (1) Protected areas notified under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972; (2) CEPI areas (3) Eco-sensitive areas and (4) Inter-state boundaries and international boundaries; are not located within 5 km or 10 km (as the case may be) area from the boundary of the proposed site. -

Drug Consumption at Wholesale Prices in 2017 - 2020

Page 1 Drug consumption at wholesale prices in 2017 - 2020 2020 2019 2018 2017 Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. Wholesale Hospit. ATC code Subgroup or chemical substance price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % price/1000 € % A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 321 590 7 309 580 7 300 278 7 295 060 8 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 2 090 9 1 937 7 1 910 7 2 128 8 A01AA Caries prophylactic agents 663 8 611 11 619 12 1 042 11 A01AA01 sodium fluoride 610 8 557 12 498 15 787 14 A01AA03 olaflur 53 1 54 1 50 1 48 1 A01AA51 sodium fluoride, combinations - - - - 71 1 206 1 A01AB Antiinfectives for local oral treatment 1 266 10 1 101 6 1 052 6 944 6 A01AB03 chlorhexidine 930 6 885 7 825 7 706 7 A01AB11 various 335 21 216 0 227 0 238 0 A01AB22 doxycycline - - 0 100 0 100 - - A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AC01 triamcinolone 113 1 153 1 135 1 143 1 A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A01AD02 benzydamine 49 0 72 0 104 0 - - A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 30 885 4 32 677 4 35 102 5 37 644 7 A02A ANTACIDS 3 681 1 3 565 1 3 357 1 3 385 1 A02AA Magnesium compounds 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AA04 magnesium hydroxide 141 22 151 22 172 22 155 19 A02AD Combinations and complexes of aluminium, 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 calcium and magnesium compounds A02AD01 ordinary salt combinations 3 539 0 3 414 0 3 185 0 3 231 0 A02B DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND 27 205 5 29 112 4 31 746 5 34 258 8 -

Application for Inclusion of Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents to the WHO

Application for inclusion of Gadolinium‐based contrast agents to the WHO Essential List of Medicines Submitted by Daniel Patiño, PhD (McMaster) Faculty of Medicine University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia Holger J. Schünemann, MD, PhD Chair and Professor, Departments of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics Co‐Director, WHO Collaborating Center for Evidence Informed Policy, McMaster University Potential conflicts of interest Dr. Patiño and Dr. Schünemann declare that they have no COI. Date: Dec 15, 2014 1 Application to add Gadolinium‐based contrast agents to the WHO Essential List of Medicines 1. Summary statement of the proposal for inclusion, change or deletion Currently the 18th edition of WHO Model List of Essential Medicines does not include gadolinium‐based contrast agents (Gd‐CAs) under 14.2 radio contrast media classification. Since the introduction of gadopentate dimeglumine in 1988, gadolinium‐based contrast agents have significantly improved the diagnostic efficacy of Magnetic Resonance Image (MRI) (1). Gadolinium‐based contrast agents are intravenous agents used for contrast enhancement with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). The Gd‐CAs are available for different types of MR scan varying from product to product, including liver, brain and whole body scan. This application proposes to add Gd‐CAs for the complementary list of WHO Essential List of Medicines to be used in the detection of lymph node metastases. It will focus on the following ‘general purpose’ Gd‐CAs: gaodopentate dimeglumine, gadodiamide, gadoversetamide, gadobenate dimeglumine, gadoteridol, gadoteric acid, gadobutrol. We will not include the ‘newer’ Gd‐CAs that are organ specific like the hepatobiliary‐specific contrast agents that are available for imaging the liver (e.g., gadoxetic acid). -

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 1/44

Estonian Statistics on Medicines 2013 DDD/1000/ ATC code ATC group / INN (rout of admin.) Quantity sold Unit DDD Unit day A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 146,8152 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01A STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 0,0760 A01AB Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment 0,0760 A01AB09 Miconazole(O) 7139,2 g 0,2 g 0,0760 A01AB12 Hexetidine(O) 1541120 ml A01AB81 Neomycin+Benzocaine(C) 23900 pieces A01AC Corticosteroids for local oral treatment A01AC81 Dexamethasone+Thymol(dental) 2639 ml A01AD Other agents for local oral treatment A01AD80 Lidocaine+Cetylpyridinium chloride(gingival) 179340 g A01AD81 Lidocaine+Cetrimide(O) 23565 g A01AD82 Choline salicylate(O) 824240 pieces A01AD83 Lidocaine+Chamomille extract(O) 317140 g A01AD86 Lidocaine+Eugenol(gingival) 1128 g A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 35,6598 A02A ANTACIDS 0,9596 Combinations and complexes of aluminium, calcium and A02AD 0,9596 magnesium compounds A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 591680 pieces 10 pieces 0,1261 A02AD81 Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium hydroxide(O) 1998558 ml 50 ml 0,0852 A02AD82 Aluminium aminoacetate+Magnesium oxide(O) 463540 pieces 10 pieces 0,0988 A02AD83 Calcium carbonate+Magnesium carbonate(O) 3049560 pieces 10 pieces 0,6497 A02AF Antacids with antiflatulents Aluminium hydroxide+Magnesium A02AF80 1000790 ml hydroxide+Simeticone(O) DRUGS FOR PEPTIC ULCER AND GASTRO- A02B 34,7001 OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE (GORD) A02BA H2-receptor antagonists 3,5364 A02BA02 Ranitidine(O) 494352,3 g 0,3 g 3,5106 A02BA02 Ranitidine(P)