Small Among Giants Television Broadcasting in Smaller Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DSO — the Swedish Experience

DIGITAL SWITCHOVER DSO — the Swedish experience Per Björkman Sveriges Television AB One of the most interesting, complicated, intriguing and political questions for the upcoming years in Europe will be the question of how to handle the spectrum in the UHF band (470 - 862 MHz). Up to now, this has been the frequency space used for analogue television but with the approaching analogue switch-off, this will change. In Sweden, the last analogue transmitter was shut down a year ago and the process for a new spectrum allocation is up and running at full speed. This article takes a closer look at the situation in Sweden. In Sweden, digital terrestrial transmissions started relatively early. Sweden was actually the second European country to launch DDT services, in March 1999, just a couple of months after the UK. During the subsequent years, it was expanded to five multiplexes (muxes), providing national coverage. Mux 1 is the Public Service (PS) bouquet with an outstanding coverage of 99.8% of the Swedish population. Muxes 2 - 4 cover some 98% of the population and Mux 5 about 70%. Today there are 30+ channels in the digital terrestrial network, most of them on subscription from the pay- TV operator Boxer. However, there is also a free-to-air choice comprising the PS channels and some commercial and local channels. In 2005, the close-down of the three analogue channels started. SVT had two channels – SVT1 on VHF and SVT2 on UHF – and the commercial broadcaster TV4 had one channel in the UHF band. During the close-down period, SVT, TV4, Teracom and the “Swedish Digital Commission” joined forces and launched a massive information campaign to prepare all households for the coming switchover. -

Rte Guide Tv Listings Ten

Rte guide tv listings ten Continue For the radio station RTS, watch Radio RTS 1. RTE1 redirects here. For sister service channel, see Irish television station This article needs additional quotes to check. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Найти источники: РТЗ Один - новости газеты книги ученый JSTOR (March 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) RTÉ One / RTÉ a hAonCountryIrelandBroadcast areaIreland & Northern IrelandWorldwide (online)SloganFuel Your Imagination Stay at home (during the Covid 19 pandemic)HeadquartersDonnybrook, DublinProgrammingLanguage(s)EnglishIrishIrish Sign LanguagePicture format1080i 16:9 (HDTV) (2013–) 576i 16:9 (SDTV) (2005–) 576i 4:3 (SDTV) (1961–2005)Timeshift serviceRTÉ One +1OwnershipOwnerRaidió Teilifís ÉireannKey peopleGeorge Dixon(Channel Controller)Sister channelsRTÉ2RTÉ News NowRTÉjrTRTÉHistoryLaunched31 December 1961Former namesTelefís Éireann (1961–1966) RTÉ (1966–1978) RTÉ 1 (1978–1995)LinksWebsitewww.rte.ie/tv/rteone.htmlAvailabilityTerrestrialSaorviewChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Freeview (Northern Ireland only)Channel 52CableVirgin Media IrelandChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 135 (HD)Virgin Media UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 875SatelliteSaorsatChannel 1 (HD)Channel 11 (+1)Sky IrelandChannel 101 (SD/HD)Channel 201 (+1)Channel 801 (SD)Sky UK (Northern Ireland only)Channel 161IPTVEir TVChannel 101Channel 107 (+1)Channel 115 (HD)Streaming mediaVirgin TV AnywhereWatch liveAer TVWatch live (Ireland only)RTÉ PlayerWatch live (Ireland Only / Worldwide - depending on rights) RT'One (Irish : RTH hAon) is the main television channel of the Irish state broadcaster, Raidi'teilif's Siranne (RTW), and it is the most popular and most popular television channel in Ireland. It was launched as Telefes Siranne on December 31, 1961, it was renamed RTH in 1966, and it was renamed RTS 1 after the launch of RTW 2 in 1978. -

Campus Cable TV Listing Channel # Alt

Campus Cable TV Listing Channel # Alt. # Channel # Alt. # Channel # Alt. # Starz (Res Halls Only) 14.1 Univision 52.11 72.11 BTN Overflow 69.8 Encore (Res Halls Only) 14.2 BET 52.13 72.13 BTN Overflow 69.10 KGAN (CBS) 16.1 79.1 BRAVO 52.15 72.15 KPXR(ION 48) Cedar Rapids 80.2 KXFA (FOX) 16.4 79.4 CNBC 52.17 72.17 KWWL-DT2 CW 80.19 KCRG (ABC) 16.6 79.6 Animal Planet 52.19 72.19 KWWL NBC HD 81.1 KWKB (CW) 16.8 79.8 USA 52.21 72.21 KWWL-DT2 CW HD 81.2 BYU 16.9 79.9 Travel Channel 52.23 72.23 KWWL-DT3 ME TV 81.3 KWWL (NBC) 16.12 79.12 CNN 53.1 73.1 KGAN-DT3 COMET 81.5 KFXB (CTN) DUBUQUE 16.16 79.16 HLN 53.3 73.3 KGAN-CBS HD 81.6 KIIN (IPTV PBS) IOWA CITY 16.18 79.18 Cartoon Network 53.5 73.5 KGAN-DT2 getTV 81.8 KWKB-DT2 THE WORKS 20.2 83.5 TBS (SD) 53.7 73.7 KCRG ABC HD 82.2 TNT 53.9 73.9 KFXA-DT3 The Country Net 82.5 SPIKE 53.11 73.11 KFXA FOX HD 82.4 ESPN HD 23.1 TV Land 53.13 73.13 KCRG-DT2 MyNet 82.6 ESPN2 HD 23.2 CMT 53.15 73.15 KFXA-DT2 Grit 82.8 TBS HD 24.1 MTV 53.17 73.17 KCRG-DT3 Antenna TV 82.10 Comcast Sports HD 24.2 Nickelodeon 53.19 73.19 QVC HD 84.1 Japanese (NHK) 25.1 MSNBC 53.21 73.21 KIIN(IPTV PBS) HD 84.2 MTVU 25.3 truTV 53.23 73.23 KIIN-DT2 (IPTV PBS) Learns 84.8 Pentacrest Camera 25.4 Food Network 54.1 74.1 KIIN-DT3 (IPTV PBS) World 84.10 Channel Listing seen may vary Big Ten Network HD 26.1 HGTV 54.3 74.1 QVC 85.1 depending upon TV manufacturer CNN HD 27.1 Disney Channel 54.7 74.7 C-SPAN 85.3 Big Ten Network HD (Alt.) 27.2 TELEMUNDO 54.9 74.9 TBN 85.5 All channels will require Lifetime HD 28.1 A&E 54.11 74.11 EVINE Live 85.9 a digital ready TV for viewing. -

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents This report covers 238 international channels/networks across 152 major operators in 34 EMEA countries. From the total, 67 channels (28%) transmit in high definition (HD). The report shows the reader which international channels are carried by which operator – and which tier or package the channel appears on. The report allows for easy comparison between operators, revealing the gaps and showing the different tiers on different operators that a channel appears on. Published in September 2012, this 168-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: A 128-page PDF giving an executive summary, comparison tables and country-by-country detail. A 40-page excel workbook allowing you to manipulate the data between countries and by channel. Countries and operators covered: Country Operator Albania Digitalb DTT; Digitalb Satellite; Tring TV DTT; Tring TV Satellite Austria A1/Telekom Austria; Austriasat; Liwest; Salzburg; UPC; Sky Belgium Belgacom; Numericable; Telenet; VOO; Telesat; TV Vlaanderen Bulgaria Blizoo; Bulsatcom; Satellite BG; Vivacom Croatia Bnet Cable; Bnet Satellite Total TV; Digi TV; Max TV/T-HT Czech Rep CS Link; Digi TV; freeSAT (formerly UPC Direct); O2; Skylink; UPC Cable Denmark Boxer; Canal Digital; Stofa; TDC; Viasat; You See Estonia Elion nutitv; Starman; ZUUMtv; Viasat Finland Canal Digital; DNA Welho; Elisa; Plus TV; Sonera; Viasat Satellite France Bouygues Telecom; CanalSat; Numericable; Orange DSL & fiber; SFR; TNT Sat Germany Deutsche Telekom; HD+; Kabel -

The Reinvention of Club RTL How RTL Belgium’S Number Two Channel Is Being Modernised

24 February 2011 week 08 The reinvention of Club RTL How RTL Belgium’s number two channel is being modernised United Kingdom France FremantleMedia and Random Destination RTL heads House produce children’s formats for southern Spain Netherlands Belgium Radio 538 looks for RTL-TVI portrays Guus Meeuwis’ supporting act the ‘real’ Dr House the RTL Group intranet week 08 24 February 2011 week 08 Cover: Stéphane Rosenblatt, Director of Television, RTL Belgium The reinvention of Club RTL 2 How RTL Belgium’s number two channel is being modernised United Kingdom France FremantleMedia and Random Destination RTL heads House produce children’s formats for southern Spain Netherlands Belgium Radio 538 looks for RTL-TVI portrays Guus Meeuwis’ supporting act the ‘real’ Dr House the RTL Group intranet week 08 “As strong and diverse as possible” RTL Belgium’s Director of Television Stéphane Rosenblatt talks about the evolving Belgian family of channels. Club RTL’s new slogan: Make your choice! Belgium - 17 February 2011 What is the strategy of RTL Belgium? Over the years RTL Belgium has created a strong, tight-knit, complementary family. Strong, because it is the clear leader in the French-speaking market in Belgium, which may be small at 4 million people, but is fiercely competitive because it is also open to French channels. Consequently, the Belgian market poses a real challenge, but this did not prevent RTL Belgium from proudly attaining a combined prime time audience share of 34 per cent in 2010. Tight-knit because our family is full of team spirit. All our teams, whether involved in production or programming, have a transversal culture. -

Gender Equality Policy in the Arts, Culture and Media Comparative Perspectives

Gender Equality Policy in the Arts, Culture and Media Comparative Perspectives Principal Investigator: Prof. Helmut K. Anheier, PhD SUPPORTED BY Project team: Charlotte Koyro Alexis Heede Malte Berneaud-Kötz Alina Wandelt Janna Rheinbay Cover image: Klaus Lefebvre, 2009 La Traviata (Giuseppe Verdi) @Dutch National Opera Season 2008/09 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. 5 List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 8 Comparative Summary ............................................................................................................ 9 Introduction to Country Reports ......................................................................................... 23 Research Questions ......................................................................................................... 23 Method ............................................................................................................................... 24 Indicators .......................................................................................................................... -

Användarguide Digital-Tv

Användarguide Digital-tv HHEMEM 11358-Anv.guide_TV020-0904.indd358-Anv.guide_TV020-0904.indd 1 009-02-049-02-04 11.21.0611.21.06 Innehåll Välkommen _________________________________________________________3 Allmänt _____________________________________________________________4 Vad finns i ditt välkomstbrev? __________________________________________4 Vad finns i ditt startpaket? _____________________________________________4 Inkoppling av separat digitalbox till tv ___________________________________5 Inkoppling av inbyggd digitalbox ___________________________________5 HDTV-box med HDMI-uttag ____________________________________________6 Koppla video/dvd med inspelningsfunktion till digitalbox __________________7 Programkort och menyinställningar _________________________________8 Nätnummer _________________________________________________________9 Digital kanalplatslista ______________________________________________10 Felsökning _________________________________________________________11 Pay-per-view ______________________________________________________13 Så här beställer du ___________________________________________________13 Radio och musik ___________________________________________________14 Music Choice ger dig perfekt musikblandning! __________________________14 Vanliga frågor och svar ____________________________________________15 Kontaktuppgifter Kundservice _____________________________________15 HHEMEM 11358-Anv.guide_TV020-0904.indd358-Anv.guide_TV020-0904.indd 2 009-02-049-02-04 11.21.0611.21.06 Välkommen att titta på -

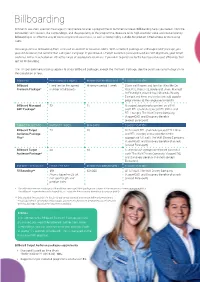

Billboarding Billboards Are Short Sponsor Messages (5 Sec) Before Or After a Programme Or Commercial Break

Billboarding Billboards are short sponsor messages (5 sec) before or after a programme or commercial break. Billboarding helps you benefit from the connection with viewers, the surroundings, and the popularity of the programme. Because of its high attention value and cost-efficiency, billboarding is an effective way of increasing brand awareness, as well as being highly suitable for product introductions or increasing sales. You can purchase billboarding from us based on content or based on GRPs. With a Content package or a Managed GRP package, you yourself decide on the content that suits your campaign. If you choose a Target Audience package based on GRP objectives, your target audience will be reached on an attractive range of appropriate channels. If you wish to purchase to the best-possible cost-efficiency, then opt for Fill boarding. The TV spot commercial policy applies to all our Billboard packages, except the Premium Package. See the purchase system diagram for the calculation of fees. CONTENT FEE/PRODUCT INDEX MINIMUM PERIOD/GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Fixed fee for the agreed Minimum period 1 week Claim well-known and familiar titles like De Premium Package* number of billboards Klok, RTL Weer, RTL Boulevard, Jinek, Married At First Sight, Weet Ik Veel, Chantals Beauty Camper and films and series (we add popular programmes to the range every month) Billboard Managed 83 15 Managed according to content on all full GRP Package* audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime and RTL Lounge), The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux (except Eurosport). TARGET AUDIENCE PRODUCT INDEX MIN GRPS CLASSIFICATION Billboard Target 78 10 All full audit RTL channels (except RTL Crime Audience Package and RTL Lounge) and a selection of the Plus* appropriate full audit The Walt Disney Company, ViacomCBS, and Discovery Benelux channels (except Eurosport). -

The World on Television Market-Driven, Public Service News

10.1515/nor-2017-0128 Nordicom Review 31 (2010) 2, pp. 31-45 The World on Television Market-driven, Public Service News Øyvind Ihlen, Sigurd Allern, Kjersti Thorbjørnsrud, & Ragnar Waldahl Abstract How does television cover foreign news? What is covered and how? The present article reports on a comparative study of a license-financed public broadcaster and an advertising- financed channel in Norway – the NRK and TV2, respectively. Both channels give priority to international news. While the NRK devotes more time to foreign news (both in absolute and relative numbers) than TV2 does, other aspects of the coverage are strikingly similar: The news is event oriented, there is heavy use of eyewitness footage, and certain regions are hardly visible. At least three explanations can be used to understand these findings: the technological platform (what footage is available, etc.) and the existence of a common news culture that is based on ratings and similar views on what is considered “good television”. A third factor is that both channels still have public service obligations. Keywords: foreign news, television news, public service Introduction The media direct attention toward events and occurrences in the world, and help to shape our thinking as well as our understanding of these events. The potentially greatest influ- ence can be expected to occur with regard to matters of which we have little or no direct experience. Foreign news is a prime example of an area where most of us are reliant on what the media report. Studies of foreign news have a long tradition (i.e., Galtung & Ruge 1965) and there is a vast body of literature focusing on the criteria for what becomes news (e.g., Harcup & O’Neill 2001; Hjarvard 1995, 1999; Shoemaker & Cohen 2006). -

Terrestrial Special

techMEDIA TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION issue-i 15 • march 2013 Terrestrial Special Plus • NEW AUDIO TECHNOLOGIES • MISSION: INTEGRATION • INTERCOM INTEROP • MEET THE TLOS • SOLVING SATELLITE JAMMING • DIGITAL AGENDA IN EUROPE and more... tech.ebu.ch viewpoint Keeping tech the digital contents-i economy Issue 15 • March 2013 on the road 3 News & Events Lieven Vermaele 4 News & Events EBU Director of Technology & Innovation 5 News & Events 6 Audio Formats ntil ten years ago the world broadband is not there only because of 7 Binaural Audio of media delivery was simple. growing public demand, but also because it Broadcast networks, whether may be a strategic asset for purchasers. 8 Member Profile: SVT Uterrestrial, satellite or cable, were Undeniably, it can be a strategy to minimize central to the delivery of media (as indeed the relevance of the terrestrial broadcast 9 IMPS they still are). Though some broadcasters platform, and by doing so, make alternative 10 700 mhz Band operated their own terrestrial transmitter but more expensive media delivery methods network, normally there was a direct the only real solution in the market. 12 SP Update: Spectrum (contractual) relationship between the media Continuing with the transport metaphor, Management organization and the network whereby the in today’s digital economy more money is 13 Media Delivery network operator’s function was simply and made with road tolls than with the services solely the transport of media services. using the roads. A fertile digital economy 14 EU Agenda With the growth of IP and broadband should be built around the services that use internet, the world of broadband media was the roads, not with the roads themselves. -

Broadcasting & Convergence

1 Namnlöst-2 1 2007-09-24, 09:15 Nordicom Provides Information about Media and Communication Research Nordicom’s overriding goal and purpose is to make the media and communication research undertaken in the Nordic countries – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – known, both throughout and far beyond our part of the world. Toward this end we use a variety of channels to reach researchers, students, decision-makers, media practitioners, journalists, information officers, teachers, and interested members of the general public. Nordicom works to establish and strengthen links between the Nordic research community and colleagues in all parts of the world, both through information and by linking individual researchers, research groups and institutions. Nordicom documents media trends in the Nordic countries. Our joint Nordic information service addresses users throughout our region, in Europe and further afield. The production of comparative media statistics forms the core of this service. Nordicom has been commissioned by UNESCO and the Swedish Government to operate The Unesco International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, whose aim it is to keep users around the world abreast of current research findings and insights in this area. An institution of the Nordic Council of Ministers, Nordicom operates at both national and regional levels. National Nordicom documentation centres are attached to the universities in Aarhus, Denmark; Tampere, Finland; Reykjavik, Iceland; Bergen, Norway; and Göteborg, Sweden. NORDICOM Göteborg -

Katso Televisiota, Maksukanavia Ja Makuunin Vuokravideoita 4/2017 Missä Ja Millä Vain

KATSO TELEVISIOTA, MAKSUKANAVIA JA MAKUUNIN VUOKRAVIDEOITA 4/2017 MISSÄ JA MILLÄ VAIN. WATSON TOIMII TIETOKONEELLA, TABLETISSA JA ÄLYPUHELIMESSA SEKÄ TV-TIKUN TAI WATSON-BOKSIN KANSSA TELEVISIOSSA. WATSON-PERUSPALVELUN KANAVAT 1 Yle TV1 12 FOX WATSONISSA 2 Yle TV2 13 AVA MYÖS 3 MTV3 14 Hero 4 Nelonen 16 Frii MAKUUNIN 5 Yle Fem / SVT World 18 TLC UUTUUSLEFFAT! 6 Sub 20 National Geographic 7 Yle Teema Channel 8 Liv 31 Yle TV1 HD 9 JIM 32 Yle TV2 HD Powered by 10 TV5 35 Yle Fem HD 11 KUTONEN 37 Yle Teema HD Live-tv-katselu. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Live-tv-katselu tv-tikun tai Watson-boksin kautta. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Live-tv-katselu Watson-boksin kautta. Ohjelma/ohjelmasarjakohtainen tallennus. Vain live-tv-katselu Watson-boksin kautta. Vain live-tv-katselu. KANAVAPAKETTI €/KK, KANAVAPAIKKA, KANAVA Next 21 Discovery Channel C 60 C More First Sports 121 Eurosport 1 HD *1 0,00 € 22 Eurosport 1 C 61 C More First HD 8,90 € 122 Eurosport 2 HD 23 MTV C 62 C More Series 123 Eurosport 2 24 Travel Channel C 63 C More Series HD 159 Fuel TV HD 25 Euronews C 64 C More Stars 160 Motors TV HD 27 TV7 C 66 C More Hits 163 Extreme Sports HD Start 33 MTV3 HD *1 C 67 SF Kanalen 200 Nautical Channel 0,00 € C 75 C More Juniori Base 126 MTV Live HD *1 C More Sport S Pakettiin sisältyy oheisella 8,90 € 150 VH1 Swedish 40 SVT1 4,30 € 41 SVT2 24,95 € tunnuksella merkityt 151 Nick Jr.