The Wallenstein Portrait Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

Lists of Appointments CHAMBER Administration Lord Chamberlain 1660-1837

Lists of Appointments CHAMBER Administration Lord Chamberlain 1660-1837 According to The Present State of the British Court, The Lord Chamberlain has the Principal Command of all the Kings (or Queens) Servants above Stairs (except in the Bedchamber, which is wholly under the Grooms [sic] of the Stole) who are all Sworn by him, or by his Warrant to the Gentlemen Ushers. He has likewise the Inspection of all the Officers of the Wardrobe of the King=s Houses, and of the removing Wardrobes, Beds, Tents, Revels, Musick, Comedians, Hunting, Messengers, Trumpeters, Drummers, Handicrafts, Artizans, retain=d in the King=s or Queen=s Service; as well as of the Sergeants at Arms, Physicians, Apothecaries, Surgeons, &c. and finally of His Majesty=s Chaplains.1 The lord chamberlain was appointed by the Crown. Until 1783 his entry into office was marked by the reception of a staff; thereafter more usually of a key.2 He was sworn by the vice chamberlain in pursuance of a royal warrant issued for that purpose.3 Wherever possible appointments have been dated by reference to the former event; in other cases by reference to the warrant or certificate of swearing. The remuneration attached to the office consisted of an ancient fee of ,100 and board wages of ,1,100 making a total of ,1,200 a year. The lord chamberlain also received plate worth ,400, livery worth ,66 annually and fees of honour averaging between ,24 and ,48 a year early in the eighteenth century. Shrewsbury received a pension of ,2,000 during his last year of office 1714-15. -

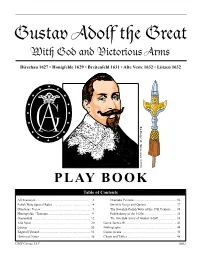

Gustavplaybook.Pdf

GustavUnder theAdolf Lily the Banners Great 11 Dirschau 1627 • Honigfelde 1629 • Breitenfeld 1631 • Alte Veste 1632 • Lützen 1632 PLAY BOOK Table of Contents All Scenarios .................................................................. 2 Dramatis Personae.................................................. 36 Polish Wars Special Rules.............................................. 4 Swedish Kings and Queens .................................... 37 Dirschau / Tczew ............................................................ 5 The Swedish-Polish Wars of the 17th Centure ...... 38 Honingfelde / Trzciano................................................... 9 Polish Army of the 1620s ....................................... 38 Breitenfeld ...................................................................... 12 The Swedish Army of Gustav Adolf ...................... 38 Alte Veste ....................................................................... 20 Game Tactics III ............................................................. 41 Lützen .......................................................................... 26 Bibliography ................................................................... 44 Edgehill Variant .............................................................. 33 Counterscans .................................................................. 45 Historical Notes .............................................................. 36 Charts and Tables ........................................................... 48 GMT Games, LLC 0602 -

![Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6001/notes-for-the-guidance-of-rep-dls-re-borough-observance-of-mourning-following-the-death-of-a-member-of-the-royal-family-not-including-the-sovereign-766001.webp)

Notes for the Guidance of Rep Dls Re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [Not Including the Sovereign]

Notes for the Guidance of Rep DLs re Borough Observance of Mourning Following the Death of a Member of the Royal Family [not including the Sovereign] The forms of Mourning are: NATIONAL MOURNING ROYAL MOURNING Following the death of a Member of The Royal Family, the Lord Chamberlain or the Earl Marshal will consult with the Prime Minister before seeking The Sovereign’s Commands with regard to mourning. No action should be taken until there is a formal announcement of the death (that is, when the media reports that Buckingham Palace or Downing Street has announced the death, not when they indicate that “reports are coming in of the death of …..”). National Mourning Observed by all, including national representatives serving abroad. Flags lowered from the day of death to the day of Funeral. Business/Sporting activities considered by Prime Minister’s Office. Royal Mourning Observed by Members of the Royal Family, Households of the Royal Family and Troops on Public Duties. Flags Flags should be flown at half-mast on the day the death is announced (or immediately following) and day of Funeral. Flags also lowered on any other occasions where Her Majesty has given special command. Half-mast means the flag is flown two-thirds of the way up the flagpole with at least the height of the flag between the top of the flag and the top of the flagpole. On flag poles that are more than 45o from the vertical, flags cannot be flown at half-mast and the pole should be left empty. When a flag is to be flown at half-mast it should first be raised all the way to the top of the mast, allowed to remain there for a second and then lowered to the half-mast position. -

The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939

THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OFARTS. By Kenna Toombs NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI AUGUST 2013 The Appeal of Fascism 2 Running Head: THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939 Kenna Toombs Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Date Dean of Graduate School Date The Appeal of Fascism 3 Abstract This thesis examines the reasons the British aristocracy became interested in fascism during the years between the First and Second World Wars. As a group the aristocracy faced a set of circumstances unique to their class. These circumstances created the fear of another devastating war, loss of Empire, and the spread of Bolshevism. The conclusion was determined by researching numerous books and articles. When events required sacrifice to save king and country, the aristocracy forfeited privilege and wealth to save England. The Appeal of Fascism 4 Contents Chapter One Background for Inter-War Years 5 Chapter Two The Lost Generation 1919-1932 25 Chapter Three The Promise of Fascism 1932-1936 44 Chapter Four The Decline of Fascism in Great Britain 71 Conclusion Fascism After 1940 83 The Appeal of Fascism 5 Chapter One: Background for Inter-War Years Most discussions of fascism include Italy, which gave rise to the movement; Spain, which adopted its principles; and Germany, which forever condemned it in the eyes of the world; but few include Great Britain. -

Wallenstein a Dramatic Poem

Open Book Classics Wallenstein A Dramatic Poem FRIEDRICH SCHILLER TRANSLATED BY FLORA KIMMICH, WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY ROGER PAULIN To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/513 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. ONLINE SURVEY In collaboration with Unglue.it we have set up a survey (only ten questions!) to learn more about how open access ebooks are discovered and used. We really value your participation, please take part! CLICK HERE Wallenstein A Dramatic Poem By Friedrich Schiller Translation and Notes to the Text by Flora Kimmich Introduction by Roger Paulin https://www.openbookpublishers.com Translation and Notes to the Text © 2017 Flora Kimmich. Introduction © 2017 Roger Paulin. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Friedrich Schiller. Wallenstein: A Dramatic Poem. Translation and Notes to the Text by Flora Kimmich. Introduction by Roger Paulin. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0101 -

Entry Task: Please Grab Your Timeline from Your Folder :)

Global Studies, December 1 Entry Task: Please grab your timeline from your folder :) Announcements: - Today: set up the Thirty Years’ War - Work on Timeline - only the top today! (Spain, England, and France) Global Studies, December 2 Entry Task: Please take out chart from yesterday - using stick figures, draw something from our notes so far on 30 Years’ War. Announcements: We’re using the white boards a few times today - keep them handy! - Today’s targets: the Thirty Years’ War - I can give a summary of the causes, key events, and effects of the 30 Years’ War. - I can organize the ideas and concepts using multimedia and graphics - Quick Review of Storyboardthat.com - Chromebooks: Please don’t pick up yet. Your drawing is not as important as your ideas! http://www.storyboardthat.com/ WHEN? 1618-1648 Thirty Years! WHERE? HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE Map by Astrokey44 Thirty Years War: Background ⦿ While the rulers of France, Spain, and Russia ruled absolutely, Central Europe was not there yet by the 1500s and 1600s Thirty Years’ War: Background ⦿ The Holy Roman Emperor had very little power since he was elected by the many German princes of his empire. France = Politically United Holy Roman Empire = Politically Divided And...don’t forget the impact of THE REFORMATION Thirty Years’ War: Background ⦿ Protestants vs. Catholics Spain= Holy Roman Religiously Empire = United Religiously Divided Read BACKGROUND chart at your table - right side Religion - how is this a factor? PEACE OF AUGSBURG 1555 Ruler of each province could decide religion Thirty Years’ War: Background ⦿ The Hapsburg family ruled the HRE since the 1450s, and they were Catholic, supported by the Pope. -

Alessandra Becucci, 2011© – Phd Candidate, European University Institute

Alessandra Becucci, 2011© – Phd candidate, European University Institute Paper presented at the 3rd Meeting of the European Network on the Theory and Practice of Biography ENTPB Biography as a Problem: New Perspectives 25-26 February 2011 – Florence, European University Institute Work in progress. Please do not quote or cite without the author’s permission A European identity: Ottavio Piccolomini (1599-1656), soldier, courtier, patron Alessandra Becucci, European University Institute The study of the cultural patronage of Ottavio Piccolomini Pieri d‟Aragona (1599-1656), Italian nobleman and soldier in the Habsburg army, as a key to understand the construction of his socio- political persona and his self fashioning1 as a soldier and a courtier at the Imperial court, accounts for the possibility to study an early modern life course in a transnational perspective. While the concept of self-fashioning as related to cultural patronage has been the object of several investigations, the study of early modern cultural investments made by Seventeenth century career soldiers has only been occasionally touched upon. As an Italian nobleman living the most of his life out of the native country, as a young pike bearer reaching the highest echelons of the imperial military hierarchy and court society, born a Sienese duke and dead an Imperial prince, Ottavio Piccolomini‟s features differentiate him from the better known typologies of art patrons, mainly by reason of the military activity, and the mobility related to it, marking his entire life2. When taking into consideration the peculiarities of his case, it is possible to try and reassess some of the ideas and conclusions drawn about Early modern cultural patronage, such as the definition of „art patron‟ itself. -

Holy Roman Empire

WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 1 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 CONTENT Historical Background Bohemian-Palatine War (1618–1623) Danish intervention (1625–1629) Swedish intervention (1630–1635) French intervention (1635 –1648) Peace of Westphalia SPECIAL RULES DEPLOYMENT Belligerents Commanders ARMY LISTS Baden Bohemia Brandenburg-Prussia Brunswick-Lüneburg Catholic League Croatia Denmark-Norway (1625-9) Denmark-Norway (1643-45) Electorate of the Palatinate (Kurpfalz) England France Hessen-Kassel Holy Roman Empire Hungarian Anti-Habsburg Rebels Hungary & Transylvania Ottoman Empire Polish-Lithuanian (1618-31) Later Polish (1632 -48) Protestant Mercenary (1618-26) Saxony Scotland Spain Sweden (1618 -29) Sweden (1630 -48) United Provinces Zaporozhian Cossacks BATTLES ORDERS OF BATTLE MISCELLANEOUS Community Manufacturers Thanks Books Many thanks to Siegfried Bajohr and the Kurpfalz Feldherren for the pictures of painted figures. You can see them and much more here: http://www.kurpfalz-feldherren.de/ Also thanks to the members of the Grimsby Wargames club for the pictures of painted figures. Homepage with a nice gallery this : http://grimsbywargamessociety.webs.com/ 2 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 3 V1V2 WAR & CONQUEST THE THIRTY YEARS WAR 1618-1648 The rulers of the nations neighboring the Holy Roman Empire HISTORICAL BACKGROUND also contributed to the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War: Spain was interested in the German states because it held the territories of the Spanish Netherlands on the western border of the Empire and states within Italy which were connected by land through the Spanish Road. The Dutch revolted against the Spanish domination during the 1560s, leading to a protracted war of independence that led to a truce only in 1609. -

The Thirty Years' War: Examining the Origins and Effects of Corpus Christianum's Defining Conflict Justin Mcmurdie George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Seminary Masters Theses Seminary 5-1-2014 The Thirty Years' War: Examining the Origins and Effects of Corpus Christianum's Defining Conflict Justin McMurdie George Fox University, [email protected] This research is a product of the Master of Arts in Theological Studies (MATS) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation McMurdie, Justin, "The Thirty Years' War: Examining the Origins and Effects of Corpus Christianum's Defining Conflict" (2014). Seminary Masters Theses. Paper 16. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/seminary_masters/16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seminary Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. A MASTER’S THESIS SUBMITTED TO GEORGE FOX EVANGELICAL SEMINARY FOR CHTH – 571-572: THESIS RESEARCH AND WRITING DR. DAN BRUNNER (PRIMARY ADVISOR) SPRING 2014 BY JUSTIN MCMURDIE THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR: EXAMINING THE ORIGINS AND EFFECTS OF CORPUS CHRISTIANUM’S DEFINING CONFLICT APRIL 4, 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Justin M. McMurdie All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART 1: THE RELIGIOUS AND POLITICAL BACKGROUND OF THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR 6 Corpus Christianum: The Religious, Social, and Political Framework of the West from Constantine to the Reformation 6 The Protestant Reformation, Catholic Counter-Reformation, and Intractable Problems for the “Holy Roman Empire of the -

Ninness on Helfferich, 'Thirty Years' War: an Anthology of Sources'

H-German Ninness on Helfferich, 'Thirty Years' War: An Anthology of Sources' Review published on Thursday, January 13, 2011 Tryntje Helfferich, ed. and trans. Thirty Years' War: An Anthology of Sources. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co., 2009. 352 pp. $42.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-87220-940-4; $14.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-87220-939-8. Reviewed by Richard J. Ninness (Touro College)Published on H-German (January, 2011) Commissioned by Benita Blessing Documenting the Thirty Years' War It is well known that we need more translations of primary sources for the early modern era. The paucity of English-language material for this period in history is a problematic lacuna. TheThirty Year War: A Documentary History responds exactly to this problem that I have often talked about. With Tryntje Helfferich's book, an instructor looking for teaching material can now turn to a collection of documents that illustrate many important aspects of the war. Helfferich's book is divided into four sections. Section 1, "Outbreak of the Thirty Years War," deals with the immediate events in 1618 that began the war and includes documents up to 1623. The second section, "The Intervention of Denmark and Sweden," covers the phase of the war when Denmark intervened and was defeated, resulting in Catholic dominance. This section includes the Edict of Restitution and documents relating to Sweden's intervention in the war along with Emperor Ferdinand's problems with Albrecht von Wallenstein--which ultimately led to the general's assassination. The Long War's third section begins with the failed Peace of Prague and demonstrates how the war dragged on. -

Round 5 2014-2015 National History Bee Varsity

ROUND 5 2015 National History Bee National Championships Round 5 - Prelims 1. In response to the growth of this group, the danka system was codified. Members of this group were burnt in straw raincoats after a successful siege of Hara castle. A practice in which icons called fumi-e were trampled was designed to identify members of this group. Members of this group were led by the teenager Amakusa Shiro in the Shimabara rebellion. For the point, name this once-persecuted Japanese religious group, which grew thanks to the activities of Francis Xavier and other Jesuits. ANSWER: Japanese Christians [or hidden Christians; or Kirishitan; prompt on "Japanese people"; prompt on "Japanese peasants"] <JB> {II} 2. During the reign of Charles VI of France, several men performing this activity while dressed in resin-soaked rags were accidentally set on fire. In a bizarre case of mass hysteria, hundreds of people compulsively performed this activity in Strasbourg during a namesake 1518 plague. A rapper sword or a longsword are sometimes used in a form of this activity known as "morris." The Black Death gave rise to an artistic motif in which skeletons engage this activity. For the point, name this activity exemplified by the minuet and the waltz. ANSWER: dancing [or dances] <JB> {II} 3. A man with this name was advised by the pope to allow marriage outside the "second degree" in the Libellus responsorium. One man of this name allied with Bertha, King Ethelbert's wife, and undertook a journey after Gregory I saw some angelic child slaves. A writer with this name described being admonished by his mother Monica after stealing some pears from a tree.