Unicode in XML and Other Markup Languages Proposed Update Unicode Technical Report #20 W3C Note XX-Xxxx-XXXX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Ng Systems Librarian the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library Agenda

Enhancing Chinese character normalization in Primo with the HKIUG TSVCC mapping table Alan Ng Systems Librarian The Chinese University of Hong Kong Library Agenda ❖ Primo out-of-box character normalization ❖ Background on CJK normalization ❖ HKIUG TSVCC mapping table ❖ Implementing TSVCC on Primo About CUHK Library ❖ established in 1963 ❖ 7 branches ❖ 200 staff ❖ 260K current patrons ❖ 130K journal subscriptions, 4.5M ebooks, 2.5M printed volumes ❖ special collections includes from oracles bones, Chinese rare books, modern Chinese literary archives … character normalization ❖ different people type differently ❖ normal to expect “Apple” will have the exact results from “aPPLE”, “ApPle”, “appLE” … ❖ before indexing, Primo will first “clean up” (normalize) the data to its lower case (e.g. A —> a, B —> b …) ❖ Primo FE will do the same for the search term typed by users, to get a match with the index Primo out-of-box normalizations ❖ Primo provides OTB normalizations for different languages at: ❖ /exlibris/primo/p4_1/ng/jaguar/home/profile/ analysis/specialCharacters/CharConversion/OTB/ OTB ❖ e.g. ❖ latin languages (non_cjk_unicode_normalization.txt) ❖ CJK (cjk_unicode_trad_to_simp_normalization.txt) OTB CJK normalization table ❖ 2700+ entries ❖ mainly for mapping Traditional Chinese into its Simplified form ❖ assume it is a 1:1 mapping, Simplified Chinese being the “lowercase” like the English language ❖ But in fact, Simplified Chinese is only one kind of variant form for Chinese character ❖ other variant forms (ideograph) of the same character need to be cover as well extract of the OTB table background on CJK ❖ Traditional Chinese characters have been used since as early as 2nd centuryBC (Han Dynasty, 漢朝) ❖ used by people in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau ❖ Simplified Chinese characters were introduced by PRC government during 1950’s ❖ used by people in PRC, SE Asia countries e.g. -

Section 18.1, Han

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Unicode in XML and Other Markup Languages

[ contents ] This document is an editor's copy. It supports markup to identify changes from a previous version. Two kinds of changes are highlighted: new, added text, and deleted text. Unicode Technical Report #20 W3C Working Group Note (Editor's Draft) 12 October 2012 This version: http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr20/tr20-9.html http://www.w3.org/International/docs/unicode-xml/ Latest version: http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr20/ http://www.w3.org/TR/unicode-xml/ Previous version: http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr20/tr20-8.html http://www.w3.org/TR/2007/NOTE-unicode-xml-20070516/ Date (Unicode): 2012-10-12 Revision (Unicode): 9 Authors: Martin Dürst ([email protected]) Asmus Freytag ([email protected]) Editor: Richard Ishida, W3C Copyright © 2012 Unicode®, and W3C® (MIT, ERCIM, Keio), All Rights Reserved. Detailed copyright information is available. Abstract This document contains guidelines on the use of the Unicode Standard in conjunction with markup languages such as XML. Status of This Document (common) This is a proposed update to a Technical Report published jointly by the Unicode Technical Committee and by the W3C Internationalization Working Group/Interest Group (W3C Members only) in the context of the W3C Internationalization Activity. This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. The base version of the Unicode Standard for this document is Version 56.2. For more information about versions of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/. -

About the Code Charts 24

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

Principles and Procedures

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N2352R 2001-09-04 Title: Principles and Procedures for Allocation of New Characters and Scripts and handling of Defect Reports on Character Names (Replaces N2352, N 2002 and N1876) Source: Ad hoc group on Principles and Procedures (Edited by: V.S. Umamaheswaran – [email protected] ) References: See References section in the document Action: To be considered by SC 2/WG 2 and all potential submitters of proposals for new characters the repertoire of ISO/IEC 10646, and for new collection identifiers Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2, ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 and Liaison Organizations This document incorporates all updates that have been approved by WG 2 up to meeting M 40 and reflecting changes to clause numbers and Annex numbers in 10646-1: 2000, and the new 10646-2: 2001. Electronic versions of this document can be found at: http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n2352r.doc, or, http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n2352r.html or, http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/n2352r.pdf. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................3 2. Allocation of New Characters and Scripts.............................................................................................................3 2.1 Goals for Encoding New Characters into the BMP 3 2.2 Character Categories 3 2.3 Procedure for Encoding New Characters and Scripts 4 2.4 WG 2 Evaluation Procedure 4 3. Handling Defect Reports on Character Names......................................................................................................5 4. -

Section 18.1, Han

The Unicode® Standard Version 12.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2019 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 12.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-22-1 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode12.0.0/) 1. -

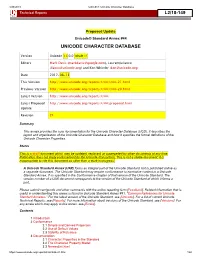

Unicode Character Database L2/18-149

4/26/2018 UAX #44: Unicode Character Database Technical Reports Proposed Update Unicode® Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 11.0.0 (draft 1) Editors Mark Davis ([email protected]), Laurențiu Iancu ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2017-08-15 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-21.html Previous Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-20.html Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Latest Proposed http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/proposed.html Update Revision 21 Summary This annex provides the core documentation for the Unicode Character Database (UCD). It describes the layout and organization of the Unicode Character Database and how it specifies the formal definitions of the Unicode Character Properties. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0--Online Edition

This PDF file is an excerpt from The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0, issued by the Unicode Consor- tium and published by Addison-Wesley. The material has been modified slightly for this online edi- tion, however the PDF files have not been modified to reflect the corrections found on the Updates and Errata page (http://www.unicode.org/errata/). For information on more recent versions of the standard, see http://www.unicode.org/standard/versions/enumeratedversions.html. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The Unicode® Consortium is a registered trademark, and Unicode™ is a trademark of Unicode, Inc. The Unicode logo is a trademark of Unicode, Inc., and may be registered in some jurisdictions. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. -

L2/10-228: Proposal to Append One CJK Unified Ideograph to The

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3885 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS 1 FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 10646TP PT Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html UTH for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.htmlUTH. See also HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html UTH for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposal to append one CJK Unified Ideograph to the URO 2. Requester's name: Joint US/UTC Contribution 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Member body 4. Submission date: 08/24/2010 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): See attached L2/10-228 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: X (or) More information will be provided later: B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: X Name of the existing block: CJK Unified Ideographs, Unified Repertoire & Ordering 2. Number of characters in proposal: 1 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary X B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Jan\Mijn Documenten\VU\Onderzoek

[23 August 2005] [SESB NA27 apparatus review for TC.wpd] 1 NA27 in SESB 1.0. A first look Jan Krans, reviewer Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam Christof Hardmeier, Eep Talsta, Alan Groves (eds.), SESB (Stuttgarter Elektronische Studienbibel / Stuttgart Electronic Study Bible), Stuttgart / Haarlem, Deutsche Bibel- gesellschaft / Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap, 2004. ISBN 3-438-01963-9 / 90-6126- 846-x. CD + Instruction Manual (ISBN 3-438-06458-8). US $ 279.95 / € 240.1 2 [1] For the first time in history, a critical apparatus to the biblical text is available in electronic form. SESB even contains the most widely used biblical texts, namely BHS and NA27, both with their apparatus. In this respect, SESB is groundbreaking.3 In this review article I will concentrate on NA27, and even further mostly on its apparatus: what are the possibilities, surprises, limitations and future prospects of the implemen- tation of NA27 in SESB 1.0? BHS and its apparatus will be regularly drawn into the discussion for comparison’s sake. Since SESB is rather limited in its documentation, quite a few examples of searches and the like will be given here. Introduction [2] Why do we have editions of the biblical text with a critical apparatus, in which variant readings are recorded? There is actually only one reason: to constantly remind us of the fact that the text we read now went through the hands (and minds) of human writers, scribes and editors before it finally reached us. Those who let this historical truth sink in, all other things shall be theirs as well. [3] Two ways could be followed to review a product such as SESB – of course, the fact that the apparatus is finally there says it all, but some questions still have to be asked –, depending on whether one is an idealist or a realist.