'O Blessed Misery!': Reading Select Poems of Swami Vivekananda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

1 EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami

EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami Vivekananda declares that education is the panacea for all our evils. According to him `man-making' or `character-building' education alone is real education. Keeping this end in view, the centres of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission have been running a number of institutions solely or partly devoted to education. The Ramakrishna Math of Bangalore (known earlier as Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama) started the `Sri Ramakrishna Vidyarthi Mandiram' in 1943, as a hostel for college boys wherein the inculcating of moral and spiritual values in the minds of the inmates was given the primary importance. The hostel became popular very soon and the former inmates who are now occupying important places in public life, still remember their life at the hostel. In 1958, the Vidyarthi Mandiram was shifted to its own newly built, spacious and well- designed, premises. In 1983, the Silver Jubilee celebrations were held in commemoration of this event. During that period a Souvenir entitled ``Education: New Dimensions'' was brought out. Very soon, the copies were exhausted. However, the demand for the same, since it contained many original and thought-provoking articles, went on increasing. We are now bringing it out as a book with some modifications. Except the one article of Albert Einstein which has been taken from an old journal, all the others are by eminent monks of the Ramakrishna Order who have contributed to the field of education, in some way or the other. We earnestly hope that all those interested in the education of our younger generation, especially those in the teaching profession, will welcome this publication and give wide publicity to the ideas contained in it. -

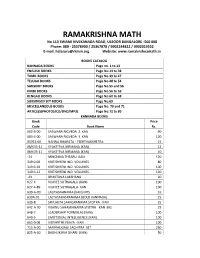

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Vivekananda College, Thiruvedakam West

VIVEKANANDA COLLEGE College with Potential for Excellence (Residential & Autonomous – A Gurukula Institute of Life-Training) (Affiliated to Madurai Kamaraj University) Reaccredited with ‘A’ Grade (CGPA 3.59 out of 4.00) by NAAC TIRUVEDAKAM WEST MADURAI DISTRICT – 625 234 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH B.A. ENGLISH LITERATURE SYLLABUS Choice Based Credit System (For those who joined in June 2015 -2016 and After) (2017-2020 Batch) ABOUT THE COLLEGE Vivekananda College was started by Founder-President Swamiji Chidhbhavanandhaji Maharaj of Sri Ramakrishna Tapovanam, Tirupparaithurai, Trichy in 1971 on the banks of the river Vaigai which is blissfully free from the noise and hurry, the crowds and distraction of the city. Vivekananda College is a residential college functioning under Gurukula pattern. It is Man-making education, that is imparted in this institution, Culture, character and curriculam are the three facets of ideal education that make man a better man. This is possible only when the teacher and taught live together, The Gurukula system of Training is therefore a humble and systematic attempt in reviving the age old GURUGRIHAVASA for wholesome education, Attention to physical culture, devotion to duty, obedience to teachers, hospitality to guests, zest for life, love for the nation, and above all, humility and faith in the presence of God etc. are the values sought to be inculcated. All steps are taken to ensure the required atmosphere for the ideal life training. Vivekananda College, Tiruvedakam West, Madurai District-625 234 is an aided college established in 1971 and offers UG and PG courses. This College is affiliated to the Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai. -

Shrines of Diverse Faiths

www.bhavanaustralia.org Let noble thoughts come to us from every side - Rigv Veda, 1-89-i Shrines of Diverse Faiths Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam “The whole world is but one family” Life | Literature | Culture May 2012 | Vol 9 No.11 | Issn 1449 - 3551 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY United States Peace Index 2012 “The last twenty years have seen a violent crime rates. Between 2000 and 2010, substantial and sustained reduction in direct New York experienced a fall in violent crime and incarceration every year, as well as falls in its violence in the United States” homicide rate. The United States Peace Index (USPI), produced Given the above findings, and the fact that 2.38% by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), of the entire population (over 7.2 million people) provides a comprehensive measure of U.S. is under some form of correctional supervision, peacefulness dating back to 1991. It also provides as well as the extent of the economic resources an analysis of the socio-economic measures that that are devoted to incarceration, it is important are associated with peace as well as estimates of to review the methods that have been used to the costs of violence and the economic benefits maintain law and order. New approaches to that would flow from increases in peace. This is the dealing with non-violent offenders, combined with second edition of the U.S. Peace Index. investments in proven recidivism programs that are cost effective hold promise in improving both This year a Metropolitan Peace Index has also the trend of crime reduction and also decreasing been produced which measures the peacefulness the rate of incarceration. -

154Th Birthday Celebration Of

154th Birthday Celebration of 15th Inter School Quiz Contest – 2016 IMPORTANT & URGENT NOTE FOR THE KIND ATTENTION OF PRINCIPALS OF SCHOOLS Std. VII to Std. IX QUIZ PLEASE PHONE & CONFIRM IN WRITING THE NUMBER OF COPIES REQUIRED : 1) QUIZ BOOKLETS : To be given in advance to interested students. 2) QUIZ QUESTION : To be kept CONFIDENTIAL until the day of PAPERS the contest at school level. 3) ANSWER SHEET : For Correction RAMAKRISHNA MATH, 12th Road, Khar (West), Mumbai - 400 052. Ph : 6181 8000, 6182 8082, 6181 8002 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.rkmkhar.org Contents Unit 1: Multiple Choice Questions(50questions) Unit 2: Fill in the Blanks 2a. Swami Vivekananda’s Utterances by theme (24 questions) 2b. Utterances of Swami Vivekananda (13 questions) 2c. Life of Swami Vivekananda (26 questions) Unit 3: Choose any one option (10 questions) Unit 4: True or False 4a. From Swamiji’s life (11 questions) 4b. From Swamiji’s utterances (8 questions) Unit 5: Who said the following 5a. Who said the following to whom (5 questions) 5b. Who said the following (10 questions) Unit 6: Answer in one line (4 questions) Unit 7: Match the following (28 questions) 7a. Events and Dates from Swamiji’s first tour to the West 7b. Incidents that demonstrate Swami Vivekananda’s power of concentration 7c. The 4 locations of the Ramakrishna Math 7d. People in Swami Vivekananda’s life who helped him in bleak situations 7e. Events in Swamiji’s life with what we can learn from them 7f. Period of Swamiji’s life with events from his life Unit 8: Identify the Pictures (16 questions) Note: Any of the questions below can be asked in any other format also. -

A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada Vivekananda

Volume 15, No. 2 • Special Edition 2009 Address all correspondence and subscription orders to: American Vedantist, Vedanta West Communications Inc. PO Box 237041 New York, NY 10023 A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada Email: [email protected] Vivekananda Movement in the Americas Volume 15 No. 2 Donation US$5.00 Special Edition 2009 (includes U.S. postage) american vedantist truth is one; sages call it variously e pluribus unum: out of many, one CONTENTS Encouraging Community among Vedantists.................2 Vivekananda’s Message to the West .............................3 Developing Vedanta in the Americas — An Interview with Swami Swahananda ..............5 A Directory of the Ramakrishna-Sarada-Vivekananda Movement in the Americas ...................................10 Reader’s Forum Question for this issue ......................................... 27 In Memoriam: Swami Sarvagatananda Swami Tathagatananda ........................................29 Response to Readers’ Forum Question in Spring 2009 issue Vivekananda and American Vedanta Sister Gayatriprana ...............................................34 The Interfaith Contemplative Order of Sarada Sister Judith, Hermit of Sarada ..............................36 MEDIA REVIEWS Basic Ideas of Hinduism and How It Is Transmitted Swami Tathagatananda Review by Swami Atmajnanananda ..................... 38 Beyond Tolerance: Searching for Interfaith Understanding in America Gustav Niebuhr Review by John Schlenck ..................................... 39 The Evolution of God Robert Wright -

Brochure-2018.Pdf

Contents About Vivekananda Human Centre 1 Editorial Board 2 Editorial 3 Programme 4-6 Message: The Queen 7 Message: Mayor of Tower Hamlets 8 Message: The High Commissioner of India 9 Message: Mr Virendra Sharma MP 10 Message: Revered President Maharaj 11 Message: Revered Swami Vagishananda 12 Message: Revered Swami Prabhananda 13 Message: Revered Swami Gautamananda 14 Message: Revered Swami Shivamayananda 15 Message: Revered Swami Suhitananda 16 Message: Revered Swami Suvirananda 17 Message: Revered Swami Ameyananda 18 Message: Revered Swami Dhruveshananda 19 The Transformation from Narendranath to Vivekananda: Revered Swami Chetanananda 20-30 Essence Of Vivekananda: Revered Swami Girishananda 31-32 Swami Vivekananda for the present - day world : Revered Swami Veetamohananda 33-34 Saints as Beacon Lights: Revered Swami Dayatmananda 35-37 Literary Genius of Swami Vivekananda: Revered Swami Bodhasarananda 38-41 Swami Vivekananda’s Message to the World – on Universal Tolerance: Revered Swami Divyananda 42-47 Swami Vivekananda As The Apostle Of World Peace: Revered Swami Atmapriyananda 48-51 Swami Vivekananda –The Monk on the Move: Revered Swami Sarvasthananda 52-55 The Dream of Peace: David Russell 56 With the Flag of Harmony: Revered Swami Sthiratmananda 57-58 Homage to Revered Swami Bhuteshanandaji Maharaj 59 Homage to Revered Swami Ranganathanandaji Maharaj 59 Homage to Revered Swami Ghananandaji Maharaj 59 Homage to Revered Swami Atmasthanandaji Maharaj 59 Homage to Revered Swami Aksharanandaji Maharaj 59 Homage to Revered Swami Prameyanandaji Maharaj 59 Vivekananda Scholarship India 60 Vivekananda Scholarship Bangladesh 60 Vivekananda Scholarship Nepal 60 Vivekananda Scholarship Gallery 61 Food Distribution 61 Photo Galleries 62-65 Advertisements 66-88 Vivekananda Human Centre “…Where should you go to seek for God? Are not all the poor, the miserable, the weak, Gods? Why not worship them first?” “…Serve as worship of the Lord Himself in the poor, the miserable, and the weak. -

In This Issue SPIRITUAL TRAILS Graceful Aging My Teacher, Swami Tapovanam

® CHINMAYA MISSION® WEST BIMONTHLY NEWSLETTER March 2010, No. 134 In This Issue SPIRITUAL TRAILS Graceful Aging My Teacher, Swami Tapovanam TraveLogUe Vande Mataram Chinmaya Dham Yatra ReFLeCTIoNS What Prayers Do Lead Me from the Unreal to the Real My Guru Is in the Driver’s Seat Pujya Gurudev’s Demand Ashtakam NewS Prabhavalis Arrive at CM Houston New Properties for CM Centers Bhumi Puja in Virginia CM Dallas/Fort Worth Family Camp Chinmaya Rameshwaram Opens CHYK Retreat CM San Diego’s Ninth Anniversary CHYK Austin Film Workshop CM New York’s CORD Walkathon Kenopanishad at CM Niagara Falls CM Minneapolis Events ANNoUNCeMeNTS Easy Sanskrit Online Course CORD USA 17th Mahasamadhi Camp Dharma Sevak Course 2010 Pujya Gurudev’s Birth Centenary Chinmaya Publications: New Arrivals CIF’s Correspondence Vedanta Courses Worship at Adi Shankara Nilayam Ottawa Awakening Canadians to India Summer CHYK Retreat CM Trinidad Summer Camp Vedanta 2010: CMW’s One-Year Course CM Chicago Summer Kids' Camps Mission Statement To provide to individuals, from any background, the wisdom of Vedanta, and the practical means for spiritual growth and happiness, enabling them to become positive contributors to society. CHINMAYA MISSION CENTERS IN NORTH AMERICA www.chinmayamission.org CENTERS in USA Arizona Minnesota Phoenix (480) 759-1541; [email protected] Minneapolis (612) 924-9172; [email protected] Arkansas New Jersey Bentonville (479) 271-0295; [email protected] Princeton (609) 655-1787; [email protected] California -

Religion Was High and He Believed in Jesus As One of the Many Christs and Not the Only Christ

THE MEHER MESSAGE [Vol. I ] December, 1929 [ No. 12] An Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook July 2020 All words of Meher Baba copyright © Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust Ahmednagar, India Source: The Meher Message THE MEHERASHRAM INSTITUTE ARANGAON AHMEDNAGAR Proprietor and Editor.—Kaikhushru Jamshedji Dastur M.A., LL.B. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust's eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust's web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba's lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects-such as lineation and font- the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. Moreover, they are often much more readable, especially in the case of older books, whose discoloration and deteriorated condition often makes them partly illegible. -

Research Scholar an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations A RIPPLE OF LOVE IN VIVEKANANDA’S POEMS Tarun Kumar Yadav Research Scholar Department of English Lalit Narayan Mithila University Darbhanga Abstract Swami Vivekananda was born in the famed Datta family of Simla, Calcutta. He was an exceptional man, well-versed in Persian and Sanskrit and had a grand penchant for law. He was a man of deep empathy and grand sympathy, and his charity very often knew no favouritism. Generally speaking, he was a monk and saint. He was not a man of singing capacity. However, he composed some unforgettable saintly poems, songs and hymns. They are a few in numbers, but they have an astounding effect. He has minutely sketched the inner exquisiteness of a man in his poems. Some of his poems are mind-boggling. His poems frankly points out the elevated aspirations of the people. The immense attachment has been shown between God and man. The internal and external beauty has been bifurcated in his poems. Since he was the devotee of the Divine Mother Kali, he has sung hymns in the love of his mother in a very impressive and earnest way. So, all his poems are teemed with pious feelings igniting the mind of readers. So the existing research paper would attempt to extract the ripple of love in Vivekananda’s poems. I would endeavour to touch most of his poems to find out the quintessence of love. Keywords: aspiration, attachment, empathy, favouritism, Kali (a powerful Goddess in Hindu religion), hymns and saintly Vivekananda, a great philanthropist, pious poet, futurist, scholar, intellect, was born on Monday 12th January 1863 in a legendary Datta family of Simla, Calcutta, India. -

LETTERS (Fifth Series)

LETTERS (Fifth Series) I Balaram Bose, February 6, 1890, Ghazipur Glory to Ramakrishna [Ghazipur February 6, 1890] Respected Sir, I have talked with Pavhari Baba. He is a wonderful saint__the embodiment of humility, devotion, and Yoga. Although he is an orthodox Vaishnava, he is not prejudiced against others of different beliefs. He has tremendous love for Mahâprabhu Chaitanya, and he [Pavhari Baba] speaks of Shri Ramakrishna as "an incarnation of God". He loves me very much, and I am going to stay here for some days at his request. Pavhari Baba can live in Samâdhi for from two to six months at a stretch. He can read Bengali and has kept a photograph of Shri Ramakrishna in his room. I have not yet seen him face to face, since he speaks from behind a door, but I have never heard such a sweet voice. I have many things to say about him but not just at present. Please try to get a copy of Chaitanya-Bhâgavata for him and send it immediately to the following address: Gagan Chandra Roy, Opium Department, Ghazipur. Please don't forget. Pavhari Baba is an ideal Vaishnava and a great scholar; but he is reluctant to reveal his learning. His elder brother acts as his attendant, but even he is not allowed to enter his room. Please send him a copy of Chaitanya-Mangala also, if it is still in print. And remember that if Pavhari Baba accepts your presents, that will be your great fortune. Ordinarily, he does not accept anything from anybody. Nobody knows what he eats or even what he does.