Country Profile Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazin 70 Jahre Kultusministerkonferenz

WÜRTTEMBERG BAYERN BADEN- BRANDENBURG BERLIN BREMEN MECKLENBURG-HAMBURG VORPOMMERNHESSEN NIEDERSACHSEN NORDRHEIN- WESTFALEN RHEINLAND-PFALZ SAARLAND SACHSEN SACHSEN-ANHALT SCHLESWIG- HOLSTEIN THÜRINGEN 26 — Prof. Dr. Olaf Köller / Robert Rauh Interview: Von Daten zu Taten – PISA, Bildungsstandards und Bildungstrends 29 — Uta-Micaela Dürig / Winfried Kneip / Dr. Jörg Dräger / Dr. Ekkehard Winter Stiftungen: Warum arbeiten Sie gerne mit der KMK zusammen? 6 — Helmut Holter 30 — Dr. Birgitta Ringbeck 68 — Anja Schöpe Weltkulturerbe – „Zukunft für unsere Vergangenheit“ Leistungsstarke Schülerinnen und Vorwort Schüler fördern 32 — Anthony Mackay 6th International Summit on the 70 — Dr. Jens-Peter Gaul / Ulrich Steinbach / Teaching Profession Uwe Gaul „Mächtiger als ein Staat: Eine gut — Ties Rabe 34 koordinierte KMK“ Gleich wertige Schulab schlüsse — Martine Reicherts — Karl-Heinz Reith — Henry Tesch 72 10 36 Europa und Erasmus+ Kulturzentrali smus oder Föderalismus? Erfahrungsbericht: Vom Schulleiter zum KMK-Präsidenten und zurück — Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hubert Esser — Prof. Dr. Rita Süssmuth 73 12 Interview: „Der Wurm muss dem Fisch schme- Kooperativer Bildungsföderalismus: — Detlef Ernst 38 WAS cken“ – Zur Zukunft der Beruflichen Bildung Vielfalt statt Einförmigkeit Erfahrungsberichte: Warum sind Auslandsschulen unabdingbar? — Hans Peter Wollseifer — Hans Ambühl 76 14 Die Attraktivität der Berufsbildung stärken Eine helvetische Betrachtung 40 — Isabel Pfeiffer-Poensgen Provenienzforschung in Deutschland — Dirk Loßack — Prof. Dr. Hans Maier -

The New Media Economics of Video-On-Demand Markets: Lessons for Competition Policy (Updated Version)

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Budzinski, Oliver; Lindstädt-Dreusicke, Nadine Working Paper The new media economics of video-on-demand markets: Lessons for competition policy (updated version) Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers, No. 125 Provided in Cooperation with: Ilmenau University of Technology, Institute of Economics Suggested Citation: Budzinski, Oliver; Lindstädt-Dreusicke, Nadine (2019) : The new media economics of video-on-demand markets: Lessons for competition policy (updated version), Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers, No. 125, Technische Universität Ilmenau, Institut für Volkswirtschaftslehre, Ilmenau This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/197010 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Ilmenau University of Technology Institute of Economics ________________________________________________________ Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers, Vol. -

Distributionplans 2011

D I S T R I B U T I O N P L A N S 2011 as amended by the Board on 20/11/2012, 04/12/2012, 27/06/2013, 18/11/2013, 04/03/2014, 17/11/2014, 18/03/2015, 19/04/2016, 15/11/2016, and as resolved by the Assembly of Shareholders and Delegates1 on 21/06/2017, 07/12/2017, 20/11/2018, 16/06/2020, 19/08/2020 and 13/11/2020 I. GENERAL 1. As long as individual shares can be established with adequate means, each rights holder shall receive their share relating to the usage of his contribution to a performance from the amount collected after deduction of the effective costs and any allocations for cultural and social purposes. 2. In cases where the individual usage share of the collected amount cannot be established with adequate means, general evaluation and distribution rules for a general approach to this method of measuring the relevant share shall be established. The scope of the usage, the cultural or artistic significance of each rights holder’s performance shall be considered adequately. Minimum thresholds for collecting usage data and setting pay-out levels to rights holders shall be permissible. 3. Any rights holders’ remuneration entitlements, their exploitation rights or other rights assigned to GVL shall be governed by the distribution plans, even if the agreement between the rights holder and the user includes deviating provisions. 4. The distribution includes: a) remuneration collected for the 2011 financial year . for broadcasts of commercially published sound recordings2 and video clips, . -

The KOF Education System Factbook: Germany

The KOF Education System Factbook: Germany Edition 1, May 2017 ETH Zurich KOF Swiss Economic Institute LEE G 116 Leonhardstrasse 21 8092 Zurich, Switzerland Phone +41 44 632 42 39 Fax +41 44 632 12 18 www.kof.ethz.ch [email protected] Table of Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................... V EDITING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................... VI 1. The German Economy and its Political System ........................................................... 1 1.1 The German Economy ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Labor Market ....................................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Overview of the German Labor Market ............................................................... 3 1.2.2 The Youth Labor Market ..................................................................................... 5 1.2.3 The KOF Youth Labor Market Index (KOF YLMI) for Germany .......................... 6 1.3 The Political System .................................................................................................. 8 1.3.1 Overview of the German Political System .......................................................... 8 1.3.2 Politics and Goals of the Education System ....................................................... 9 2. Formal System of Education ....................................................................................... -

TV - Programme Stand: 02.06.2008

TV - Programme Stand: 02.06.2008 Decoderkanal* primatv Basis Sprache Dienste Decoderkanal* primatv Maxi Sprache Dienste 1 Das Erste deutsch TXT 60 13th STREET deutsch 2 ZDF deutsch TXT 61 Kinowelt deutsch TXT 3 Sat.1 deutsch TXT 62 Sci Fi deutsch 4 RTL deutsch TXT 63 Silverline (9.00 - 03.00) deutsch 5 ProSieben deutsch TXT 64 AXN deutsch 6 RTL 2 deutsch TXT 65 Extreme Sports Channel englisch 7 VOX deutsch TXT 66 ESPN Classic Sport englisch 8 Super RTL deutsch TXT 67 Motors TV dt. / engl. 9 Kabel 1 deutsch TXT 68 Romance TV deutsch 10 Das Vierte deutsch TXT 69 THE ADULT CHANNEL (23.00 - 5.00) englisch 11 KiKa deutsch TXT 70 blue Hustler (23.00 - 6.00) englisch 12 Nick deutsch TXT 71 The History Channel deutsch 13 Tele 5 deutsch TXT 72 National Geographic (9.00 - 2.00) deutsch 14 9Live deutsch TXT 74 Wein TV deutsch 15 MDR Sachsen deutsch TXT 75 BBC World englisch 16 hr-fernsehen deutsch TXT 76 Fashion TV englisch 17 rbb Berlin deutsch TXT 77 Club dt. / engl. 18 SWR Fernsehen RP deutsch TXT 78 Sailing Channel dt. / engl. 19 3sat deutsch TXT 79 Trace französisch 20 arte deutsch TXT 80 MEZZO französisch 21 EinsExtra deutsch TXT 22 EinsFestival deutsch TXT Decoderkanal* primatv MTV Sprache Dienste 23 EinsPlus deutsch TXT 90 MTV TWO deutsch 24 ZDFdokukanal deutsch TXT 91 MTV Dance deutsch 25 ZDFinfokanal deutsch TXT 92 MTV HITS deutsch 26 ZDFtheaterkanal deutsch TXT 93 VH-1 englisch 27 Leipzig Fernsehen deutsch TXT 94 VH-1 Classic englisch 28 Chemnitz Fernsehen deutsch 29 Dresden Fernsehen deutsch Decoderkanal* primatv arena Sprache Dienste -

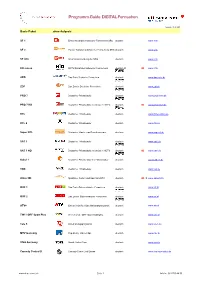

Programm-Guide DIGITAL-Fernsehen

Programm-Guide DIGITAL-Fernsehen Ausgabe Dez. 2007 Basic-Paket ohne Aufpreis SF 1 Erster Kanal des Schweizer Fernsehens SRG deutsch www.sf.tv SF 2 Zweiter Kanal des Schweizer Fernsehens SRG deutsch www.sf.tv SF info Informationssendung der SRG deutsch www.sf.tv HD suisse HDTV-Kanal des Schweizer Fernsehens deutsch./it HD www.sf.tv ARD Das Erste Deutsche Fernsehen deutsch www.daserste.de ZDF Das Zweite Deutsche Fernsehen deutsch www.zdf.de PRO 7 Deutscher Privatsender deutsch www.prosieben.de PRO 7 HD Deutscher Privatsender, teilweise in HDTV deutsch HD www.prosieben.de RTL Deutscher Privatsender deutsch www.rtl-television.de RTL 2 Deutscher Privatsender deutsch www.rtl2.de Super RTL Deutscher Kinder- und Familiensender deutsch www.superrtl.de SAT 1 Deutscher Privatsender deutsch www.sat1.de SAT 1 HD Deutscher Privatsender, teilweise in HDTV deutsch HD www.sat1.de Kabel 1 Deutscher Privatsender mit Filmklassiker deutsch www.kabel1.de VOX Deutscher Privatsender deutsch www.vox.de Anixe HD Spielfilme, Serien und Sport in HDTV deutsch HD ● www.anixehd.tv ORF 1 Das Erste Österreichische Fernsehen deutsch www.orf.at ORF 2 Das Zweite Österreichische Fernsehen deutsch www.orf.at ATV+ Österreichisches Unterhaltungsprogramm deutsch www.atv.at TW1 / ORF Sport Plus Wetterkanal / ORF Sport Highlights deutsch www.tw1.at Tele 5 Unterhaltungsprogramm deutsch www.tele5.de MTV Germany Pop-Musik, Video-Clips deutsch www.mtv.de VIVA Germany Musik, Video-Clips deutsch www.viva.tv Comedy Central D Comedy-Serien und Shows deutsch www.comedycentral.de www.rii-seez-net.ch Seite 1 Infoline 081 755 44 99 Programm-Guide DIGITAL-Fernsehen Ausgabe Dez. -

Between Reformstau and Modernisierung: the Reform Of

Between Reformstau and Modernisierung: The Reform of German Federalism since Unification Gunther M. Hega Department of Political Science Western Michigan University 1903 W. Michigan Avenue Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5346 E-mail: [email protected] 1. Draft -- October 22, 2003 Please do not quote without the author’s permission Paper to be presented at the Conference on “Europeanization and Integration” EU Center of the University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, October 24 – 25, 2003 Abstract: Between Reformstau and Modernisierung: The Reform of German Federalism since Unification This paper examines the changes of the German federal system and the role of the 16 states (Länder) in national politics and policy-making in the Federal Republic of Germany since 1990. In particular, the study focuses on the response of the German Federal Council (Bundesrat), the chamber of the national parliament which represents the Länder, to the processes of German unification and European integration in the last decade. The paper starts from the assumption that the Federal Council has been the chief beneficiary among the Federal Republic's political institutions of the trends toward "unitary federalism" at the domestic level and a "federal Europe" at the international level. Due to the evolution of cooperative federalism with its interlocking policies, the changes in the party system and coalition politics, and, in particular, the twin processes of German unification and European integration, the Bundesrat has gained additional, special powers by assuring the inclusion of the "subsidiarity principle" in both the German Constitution (the Basic Law) and the Maastricht Treaty on European Union. The amended Article 23 of the Basic Law and the Maastricht Treaty's Article 3b strengthen the participation of the Federal Council and the 16 German states in national and European policymaking. -

ANT Kabelanschluss.Pdf

ANALOGE FERNSEHPROGRAMME K5 ZDF S23 Phönix K6 NDR S24 MTV K7 Pro 7 S25 QVC K8 Eurosport S39 SIXX K9 ARD S41 Sport 1 K10 Sat 1 K21 K-TV K11 MDR K22 TW 1 K12 CNN K23 Hitradio Ö3 (Testsendung) S6 Anixe SD K24 Hitradio Ö3 (Testsendung) S7 KiKa K25 de luxe Musik S8 Super RTL K26 Nick S9 Kabel 1 K27 imusic TV S10 Rudolstadt TV K28 SF Info (Testsendung) S11 RTL Televison K29 SF Info (Testsendung) S12 WDR K30 arte S13 VIVA K31 Go TV S14 SW 3 Baden-Württemberg K32 HSE24 S15 Das Vierte K33 Tele 5 S16 RTL 2 K34 Bibel TV S17 3sat K35 DMAX S18 Bayern 3 K36 Hitradio Ö3 (Testsendung) S19 Vox K37 ZDF Doku S20 n-tv K38 BR alpha S21 rbb K39 N 24 S22 Hessen 3 Aktuelle Programmänderungen finden Sie bei Rudolstadt TV (im Videotext ab Seite 120) oder im Internet unter www.rudolstadt-net.de Digitaler Kabelanschluss TV TV International ARM 1, BET, BBC World, S3 121 MHz TV1 Rusia-Europe, CNNi, verschlüsselt mit CTW: JSTV 1 MTV networks MTV Germ., Viva, Comedy Central/NICK, S4 129 MHz verschlüsselt mit CTW : MTV Music, MTV NL, MTV Premium, MTV Idol ARD digital MDR, rbb Be, SWR-Fernsehen Rheinland-Pfalz S 26 346 MHz rbb Brdbg., NDR MV, NDR HH, NDR NDS, NDR Symbolrate 6900 MDR Sa, MDR Sa-An, MDR Th, ZDF Vision ZDF, 3sat, KiKa, ZDFinfokanal, ZDFdokukanal, S 27 354 MHz ZDFtheaterkanal Sky* Sky Transponder 81 S 28 362 MHz Sky* Sky Transponder 69 S 29 370 MHz Sky* Sky Transponder 67 S 30 378 MHz Sky* Sky Transponder 65 S 31 386 MHz Sky* Sky Transponder 83 S 32 394 MHz RTL Group RTL, RTL II, Super RTL, VOX, S 33 402 MHz n-tv, RTL Shop, Channel 21 Shop ARD digital Das Erste, Bayrisches Fernsehen Süd, hr-fernsehen, Bayr. -

Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag Umdruck 18/2788

ZWEITES DEUTSCHES FERNSEHEN Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts DER INTENDANT Bericht über die wirtschaftliche und finanzielle April 2014 Lage des ZDF ZDFPresse_vorOrt-Produktionen-allgemein.indd 2 22.06.12 16:14 I. GEMEINSAME ERKLÄRUNG VON ARD, DEUTSCHLANDRADIO UND ZDF 1 II. BERICHT ÜBER DIE WIRTSCHAFTLICHE LAGE DES ZDF 4 1. Kennzeichen der Finanzpolitik des ZDF 4 1.1 Grundsätzliche Überlegungen 4 1.2 Einsparleistungen des ZDF 5 1.3 Wirtschaftlichkeit und Sparsamkeit 7 1.3.1 Gebührenperiode 2009 - 2012 8 1.3.2 Beitragsperiode 2013 - 2016 8 1.4 Umsetzung der KEF-Vorgaben 10 2. Ergebnisse des 19. KEF-Berichts und Bewertung 12 2.1 Vorbemerkungen 12 2.2 Ergebnisse des 19. KEF-Berichts 12 2.2.1 Empfehlungen der KEF zur Höhe des Rundfunkbeitrags 12 2.2.2 Anerkannter Finanzbedarf 13 2.3 Zusammenfassende Bewertung 14 2.4 Übersicht über die Haushaltsentwicklung in den Jahren 2011 - 2014 14 2.4.1 Geschäftsjahr 2011 17 2.4.2 Geschäftsjahr 2012 18 2.4.3 Geschäftsjahr 2013 19 2.4.4 Geschäftsjahr 2014 20 2.5 Übersicht über die mittelfristige Finanzplanung 2013 - 2016 22 2.5.1 Erträge 23 2.5.2 Personalaufwendungen 24 2.5.3 Programmaufwendungen 25 2.5.4 Geschäftsaufwendungen 26 3. Erfüllung des Programmauftrags 27 3.1 Fernsehen 27 3.1.1 ZDF 27 3.1.2 Digitale Ergänzungskanäle 37 3.1.2.1 ZDFneo 37 3.1.2.2 ZDFinfo 39 3.1.2.3 ZDFkultur 40 3.1.3 Europäischer Kulturkanal ARTE 41 3.1.4 Ereignis- und Dokumentationskanal PHOENIX 43 3.1.5 3sat 44 3.1.6 Kinderkanal (KiKA) 45 3.1.7 Multimediales Jugendangebot von ARD und ZDF 46 3.2 Online-Angebot 48 3.3 Technische Umsetzung des Programmauftrags 50 3.3.1 Terrestrik 51 3.3.2 Kabel und Satellit 51 3.3.3 Neue Übertragungswege 52 3.3.4 Aktuelle technologische Entwicklungen 53 4. -

The Education System in the Federal Republic of Germany 2017/2018

The Education System in the Federal Republic of Germany 2017/2018 A description of the responsibilities, structures and developments in education policy for the exchange of information in Europe – EXCERPT – 11. QUALITY ASSURANCE 11.1. Introduction The debate about evaluation in the education system, in other words the systematic assessment of organisational structures, teaching and learning processes and per- formance criteria with a view to improving quality, did not start in Germany until the end of the 1980s, later than in other European countries. Although the actual concept of evaluation may not yet have been institutionalised before, this does not mean that no control mechanisms existed. State supervisory authorities for schools and higher education, statistical surveys carried out by the Federal Statistical Office and by the Statistical Offices of the Länder as well as educational research in insti- tutes that are subordinate to federal or Land ministries or jointly funded by the Fed- eral Government and the Länder are used for quality assurance and evaluation pur- poses. Within the school system, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Länder (Kultusministerkonferenz – KMK), in the so-called Konstanzer Beschluss of October 1997, took up quality assurance processes that had already been introduced in several Länder in the school sector and declared these a central issue for its work. Since then the Länder have developed evaluation instru- ments in the narrower sense which may be employed depending on the objective. In 2003 and 2004, educational standards were adopted for the primary sector, the Hauptschulabschluss and the Mittlerer Schulabschluss. -

HINTERGRUNDINFORMATION Übersicht Öffentlich-Rechtlicher

HINTERGRUNDINFORMATION Übersicht öffentlich-rechtlicher Fernsehprogramme Berliner Runde\InhaltBriefingMappe 280807\Hintergrundinformation_oerr_tv_programme_280807_FINAL.doc Öffentlich-rechtliche Fernsehprogramme 2007 insgesamt = 22 Vollprogramme und 22 Regionalfenster ARD-Programme = 14 + 22 Regionalfenster ZDF-Programme = 4 ARD/ZDF-Programme = 4 ARD/ZDF-Datendienste = je 2 Terrestrische Verbreitung: o terrestrisch verbreitete Programme insgesamt = 20 + 22 Regionalfenster + 2 Datendienste o Programme über analoge Antenne = 9 o Programme über DVB-T = 19 + 22 Regionalfenster + 2 Datendienste o Programme über analoge Antenne, aber nicht DVB-T = 1 (SR Fernsehen Südwest) o Datendienste über DVB-T = 2 o Mediendienste über UMTS = 1 („tagesschau in 100 Sekunden) Kabel-Verbreitung: o über Kabel verbreitete Programme insgesamt = 22 + 22 Regionalfenster o Programme im analogen Kabel = 22 + 22 Regionalfenster o Programme im digitalen Kabel = 22 + 22 Datendienst Satelliten-Verbreitung: o über Satellit verbreitete Programme insgesamt = 22 + 22 Regionalfenster o Programme über DVB-S = 22 + 22 Regionalfenster o Programme über analogen Satelliten = 15 + 5 Regionalfenster 2 Online-Verbreitung: o Programme über IPTV = 22 + 11 Regionalfenster o Programme über Web-TV (Livetream der kompletten Sendung) = 1 (Ki.Ka) o Programme mit Livestream von Einzelsendungen = 8 o Einzelsendungen als Livestream = 44 (ARD = 7, Dritte = 25, ZDF = 7, Phoenix = 5) o reine Webchannel (Stream-Loop von Einzelsendungen) = 1 (beim NDR) On-Demand-Angebote von Programmausschnitten: o Podcasting-Portale insgesamt = 83 o Podcasting-Portale für Videocasts = 65 o Podcasting-Portale für Audiocasts = 65 o Programme, die Inhalte für Podcasts liefern = 9 o Programm-Websites die Videofiles anbieten = 15 o Zahl der Portale für Videofiles = 256 1 o Programm-Websites die Community-Portale anbieten = 1 2 1 Es gibt zwei Portal-Typen und zwei Sortierungsversionen. -

Fischer, Anikó Verjüngungsstrategien Im Öffentlich- Rechtlichen Fernsehen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver der Hochschule Mittweida !"#$%&'&(#$)*&+(&, !(-#$&'.)/,(01 2&'34,56,5--7'"7&5(&,)(8)9::&,7;(#$< '&#$7;(#$&,)!&',-&$&,)=)>9,,&,) ?,;(,&",5&%@7&)36,5&)A6-#$"6&')+"6&'$":7) ",)+(&)9::&,7;(#$<'&#$7;(#$&,)B&,+&')%(,+&,C <)D"#$&;@'"'%&(7)< E@#$-#$6;&)*(77F&(+")G!EH)=)I,(J&'-(7K)@:)/LL;(&+)B#(&,#&- >9;,)<)MNNO !"#$%&'&(#$)*&+(&, !(-#$&'.)/,(01 2&'34,56,5--7'"7&5(&,)(8)9::&,7;(#$< '&#$7;(#$&,)!&',-&$&,)=)>9,,&,) ?,;(,&",5&%@7&)36,5&)A6-#$"6&')+"6&'$":7) ",)+(&)9::&,7;(#$<'&#$7;(#$&,)B&,+&')%(,+&,C <)&(,5&'&(#$7)";-)O"#$&;@'"'%&(7)< D@#$-#$6;&)*(77E&(+")F!DG)=)H,(I&'-(7J)@:)/KK;(&+)B#(&,#&- P'-7K'4:&' AE&(7K'4:&' Q'@:R)S'R)?77@)/;7&,+@':&' *(#$"&;)O6-#$ >9;,)<)LMMN !"#$"%&'()*"+,*-.!-+,*'-"#/0& 1"+,*-'2.30"456 7-'890&/0&++:'(:-&"-0.";.<==-0:$",*>'-,*:$",*-0.1-'0+-*-0.?.@<00-0.A0$"0-(0&-#%:-. 8/0&-.B/+,*(/-'.C(/-'*(=:.(0.C"-.<==-0:$",*>'-,*:$",*-0.D-0C-'.#"0C-0E.>.FGGH.?.IG.DJ. @<$02.K%,*+,*/$-.L"::M-"C(.N1KO2.1(,*#-'-",*.L-C"-02.!(,*-$%'('#-": P-=-'(: Q0.C-'.R%'$"-&-0C-0.!(,*-$%'('#-":.&"$:.-+.*-'(/+S/="0C-02."0M"-=-'0.<==-0:$",*>'-,*:$",*-. A0$"0-(0&-#%:-.S/'.B/+,*(/-'R-'890&/0&.";.1-'0+-*-0.#-":'(&-0.4<00-0J 30*(0C.'-)'T+-0:(:"R-'.D:/C"-0.M"'C.C"-.L-C"-00/:S/0&.C-'.C-/:+,*-0.!-R<$4-'/0&. /0:-'+/,*:./0C.(/+&-M-':-:J.U-'.1%4/+.M"'C.(/=.C"-.V-0-'(:"%0.C-'./0:-'.WG>XT*'"&-0. &-$-&:J. U('(/=.=%$&-0C.M-'C-0.C"-.D:'(:-&"-0.C-'.Y'%&'(;;(0#"-:-'.S/'.B/+,*(/-'R-'890&/0&. /0C.C-'-0.A0$"0-(0&-#%:-.C('&-+:-$$:J. Z(,*.C-'.3/+M-':/0&.C-'.['&-#0"++-.=%$&:.-"0-.Q0:-')'-:(:"%02.-"0.1(S":./0C.-"0.4/'S-'.