The Corporate Chieftain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Report Celebrations, Competitions & Community

2016 Annual Report Celebrations, Competitions & Community www.SpecialOlympicsGA.org Table of Mission Contents Special Olympics Georgia provides year-round sports training and athletic competition in a variety of Olympic-type sports for children and adults with intellectual disabilities, giving them continuing Letter from the Board opportunities to develop physical fitness, demonstrate courage, Chairman and CEO experience joy and participate in the sharing of gifts, skills and 3 friendships with their families, other Special Olympics athletes and the community. Sports Offered and State Competitions Special Olympics Georgia, a 501c3 nonprofit organization, is supported by donations 4 from individuals, events, community groups, corporations and foundations. Special Olympics Georgia does not charge athletes to participate. The state offices are located at 4000 Dekalb Technology Parkway, Building 400, Suite 400, Atlanta, GA Beyond Sports: Healthy 30340 and 1601 N. Ashley Street, Suite 88, Valdosta, GA 31602. 770-414-9390. Athletes & Unified Sports www.SpecialOlympicsGA.org. 5 Meet Our Athletes: Marcus & Elena 6 2016 Fundraising Highlights: Law Enforcement Torch Run & Special Events 7 2016 Financial Review 8 Meet Our Team 9-10 2016 Sponsors and Contributors Recognition “Let Me Win. But If I Cannot Win, 11-15 Let Me Be Brave In The Attempt.” Special Olympics Athlete Oath 2 A MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD AND CEO Dear Friends and Fans, In 1970, 500 Special Olympics Georgia (SOGA) athletes trained and participated in the first-ever competition held within our organization. 46 years later, we are in amazement at the continued growth of activity and support our organization has seen. 2016 was a year filled with celebrations of friendships and accomplishments, competitions that showcased bravery and sportsmanship, and newly formed relationships within communities across Georgia. -

Public Taste: a Comparison of Movie Popularity and Critical Opinion

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion R. Claiborne Riley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Riley, R. Claiborne, "Public taste: A comparison of movie popularity and critical opinion" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625207. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-hqz7-rj05 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLIC TASTE: A COMPARISON OF MOVIE u POPULARITY AND CRITICAL OPINION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology The College of William, and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by R. Claiborne Riley 1982 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts R. Claiborne Riley Approved, September 1982 r**1. r i m f Satoshi Ito JL R. Wayne Kernodle Marion G. Vanfossen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......... iv LIST OF TABLES . ..... .... ..................... v ABSTRACT .......... '......... vi INTRODUCTION .......... ...... 2 Chapter I. THE MOVIES: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE .............. 6 Chapter II. THE AUDIENCE ........................................ 51 Chapter III. THE C R I T I C ............ 61 Chapter IV. THE WANDERER STUDY AND DUMAZEDIER ON MOVIES AND LEISURE ....... -

Leseprobe L 9783570501061 1.Pdf

Donald R. Keough Die 10 Gebote für geschäftlichen Misserfolg Vorwort von Warren Buffett Aus dem Englischen von Helmut Dierlamm Die amerikanische Originalausgabe erschien 2008 unter dem Titel »The Ten Commandments for Business Failure« bei Portfolio, einem Unternehmen der Penguin Group (USA) Inc., New York. Dieses Buch ist den Millionen Männern und Frauen auf der ganzen Welt gewidmet, die in Vergangenheit, Gegenwart und Zukunft der Coca-Cola-Familie angehören. Umwelthinweis Dieses Buch wurde auf 100 % Recycling-Papier gedruckt, das mit dem blauen Engel ausgezeichnet ist. Die Einschrumpffolie (zum Schutz vor Verschmutzung) ist aus umweltfreundlicher und recyclingfähiger PE-Folie. 1. Auflage © 2009 der deutschsprachigen Ausgabe Riemann Verlag, München in der Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH © 2008 Donald R. Keough All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition published by arrangement with Portfolio, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Lektorat: Ralf Lay, Mönchengladbach Satz: Barbara Rabus Druck und Bindung: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck ISBN 978-3-570-50106-1 www.riemann-verlag.de Inhalt Vorwort von Warren Buffett . 7 Einleitung . 11 Das erste Gebot – ganz oben auf der Liste – Gehen Sie keine Risiken ein . 21 Das zweite Gebot Seien Sie inflexibel . 34 Das dritte Gebot Isolieren Sie sich . 53 Das vierte Gebot Halten Sie sich für unfehlbar . 66 Das fünfte Gebot Operieren Sie stets am Rand der Legalität . 73 Das sechste Gebot Nehmen Sie sich keine Zeit zum Denken . 86 Das siebte Gebot Setzen Sie Ihr ganzes Vertrauen in Experten und externe Berater . 101 Das achte Gebot Lieben Sie Ihre Bürokratie . 117 Das neunte Gebot Vermitteln Sie unklare Botschaften . -

Broadcastingaor9 ? Ci5j DETR 4, Eqgzy C ^:Y Reach the 'Thp of the World with Fitness News

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E BroadcastingAor9 ? ci5j DETR 4, EqGzY C ^:y Reach The 'Thp Of The World With fitness News. Nothing delivers Minnesota like Eyewitness News. Five stations of powerful news programming reaching 90% of the state. When you're looking for the top of the world, remember Eyewitness News. Represented nationally by Petry. Hubbard Broadcasting's Minnesota Network: KSTP-TV KSAX TV KRWF-TV WDIO -TV WIRT-TV APR. 1 1 1990 111 Lì,rJ_ ' -- . , ,. .n ..... -... ---_- -- -- ,--. Seattle KSTW Honolulu KGMB A BIGGER PAYOFF IS COMING This FALL! Anyone can say they have the "show of the '90s". But THE JOKER'S WILD is the one showing you clearances week after week. NOW 10 OF THE TOP 10! With a promotional package second to none, THE JOKER'S WILD is playing to win this Fall! PRODUCTION STARTS MAY 20th AT CBS TELEVISION CITY! JVummUNIUMI iun; Production A CAROLCO PICTURES COMPANY NEW YORK LOS ANGELES CHICAGO (212) 685 -6699 (213) 289 -7180 (312) 346-6333 Vol. 118 No. 15 Broadcasting ii Apr 9 Subcommittee Chairman 95/ PIONEER ENGINEER Daniel Inouye says that based Hilmer Swanson, senior staff 35/ NAB '90: highlights on views of committee members, telephone company scientist for Harris Corp.'s broadcast division, has from Atlanta entry "may be close call." NAB's annual convention in Atlanta provides forum for discussing competitive challenges facing 66/ TELCO BAN GOES broadcasters from cable, DBS and telcos; BACK TO GREENE "interference consequences" of TV Marti (page 43); U.S. -

Brian 73334 74470 Bank of America’S Brian Moynihan

IA.coverA1.REVISE2.qxd 7/10/09 1:15 PM Page 1 IRISHIRISHAugust/September 2009 AMERICA AMERICACanada $4.95 U.S.$3.95 THE GLORY DAYS OF IRISH IN BASEBALL JUSTICE ROBERTS’ IRISH FAMILY MEMORIES OF THE GREAT HUNGER THE WALL STREET 50 HONORING THE IRISH IN FINANCE The Life DISPLAY UNTIL SEPT. 30, 2009 08 of Brian 74470 73334 Bank of America’s Brian Moynihan on family, Ireland and 09 what the future holds > AIF-Left 7/9/09 12:08 PM Page 1 AIF-Left 7/9/09 12:08 PM Page 2 MutualofAmerica 7/6/09 11:15 AM Page 1 WaterfordAD 7/10/09 2:06 PM Page 1 IA.38-41.rev.qxd 7/10/09 7:36 PM Page 38 38 IRISH AMERICA AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2008 IA.38-41.rev.qxd 7/10/09 7:36 PM Page 39 WAL L STREET50 KEYNOTE SPEAKER THE LIFE OF Brian Bank of America’s Brian Moynihan says “It doesn’t all break your way all the time, so you’ve got to just power through it.” e has the look of an athlete, com- “He has proved in difficult environments he is pact with broad shoulders. He also very capable,” said Anthony DiNovi, co-president of has something of a pre-game Boston private-equity firm Thomas H. Lee Partners focus, a quiet intensity, and gives LP, in a Wall Street Journal article by Dan the impression, even as he Fitzpatrick and Suzanne Craig. The article addressed answers questions, that he has his Moynihan’s emergence as a right-hand man and eye on the ball and he’s not forget- potential successor to Bank of America Corp. -

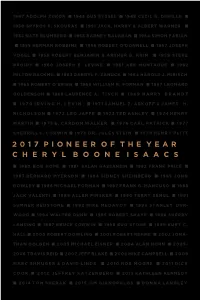

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

Coca-Cola 10-K

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ፤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2011 OR អ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 001-02217 20FEB200902055832 (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 58-0628465 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) One Coca-Cola Plaza Atlanta, Georgia 30313 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (404) 676-2121 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered COMMON STOCK, $0.25 PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ፤ No អ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes អ No ፤ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ፤ No អ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

Coca Cola Co

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 2007-02-21 | Period of Report: 2006-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001047469-07-001328 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER COCA COLA CO Mailing Address Business Address ONE COCA COLA PLAZA ONE COCA COLA PLAZA CIK:21344| IRS No.: 580628465 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 30313 ATLANTA GA 30313 Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-02217 | Film No.: 07638901 4046762121 SIC: 2080 Beverages Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT ý OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2006 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE o ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 1-2217 (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 58-0628465 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) One Coca-Cola Plaza 30313 Atlanta, Georgia (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (404) 676-2121 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered COMMON STOCK, $0.25 PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

UNIVERSAL TV-Leading Supplier of TV Series to the Itself of the Talent

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF TELEVISION 441 UNIVERSAL TV-leading supplier of TV series to the period. Robert Stack played Eliot Ness, head of the "un- networks since the mid -60s, usually having three times the touchable" government agents cracking down on the mobs. number of weekly hours on the air as the runner-up Hol- Although it was highly popular, the series was attacked lywood studio. A subsidiary of Universal Pictures, UTV has by Italian -American groups for ethnic defamation and by been responsible for such series as Ironside, Kojak, Columbo, others for the sensationalism of machine-gun murders and Baretta, Emergency, The Rockford Files, Rich Man, Poor Man acts of brutality. It was produced by Quinn Martin for and the NBC World Premiere movies, among scores of other Desilu, in association with Langford Productions. shows. Its sister company, MCA -TV, engaged in domestic and foreign syndication, habitually turns huge profits from the network hits through the sale of reruns. Universal Pictures was a foundering company when the talent agency MCA (originally, Music Corp. of America) bought control of the studio in 1962. MCA then divested itself of the talent agency and concentrated on making movies, television series and recordings (it had also pur- chased Decca Records). Earlier, MCA had bought the old Republic film studios and created Revue Productions, which turned out low -budget TV series. With Universal, MCA Inc. had the largest studio in Hollywood and the best- equipped backlot, and the show -business savvy of its princi- pal officers, Jules Stein and Lew Wasserman, quickly turned the facilities into a giant TV production source. -

Coca-Cola Company 10-K

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ፤ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 OR អ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 001-02217 20FEB200902055832 (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) DELAWARE 58-0628465 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) One Coca-Cola Plaza Atlanta, Georgia 30313 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (404) 676-2121 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered COMMON STOCK, $0.25 PAR VALUE NEW YORK STOCK EXCHANGE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ፤ No អ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes អ No ፤ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ፤ No អ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

The Journey to Democracy: 1986-1996

The Journey to Democracy: 1986-1996 The Carter Center January 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Foreword by Jimmy Carter 2. Introduction by Robert Pastor 3. Timeline 4. Chapter 1: One Journey To Democracy 5. Chapter 2: Defining a Mission 6. Chapter 3: Election Monitoring and Mediating 7. Chapter 4: The Hemispheric Agenda 8. Chapter 5: The Future Appendices I. Latin American and Caribbean Program Staff II. The Council of Freely Elected Heads of Government III. LACP, The Carter Center, and Emory University IV. Publications and Research V. Program Support VI. Some Participants in Conferences and Election-Monitoring Missions FOREWORD As president, I gave Latin America and the Caribbean high priority for several reasons. First, I believed that U.S. relations with our neighbors were among the most important we had for moral, economic, historical, and strategic reasons. Second, in the mid-1970s, the United States had a compelling interest in negotiating new Panama Canal Treaties and in working with democratic leaders and international organizations to end repression and assure respect for human rights. Third, I had a long-term personal interest in the region and had made several rewarding trips there. When I established The Carter Center, I was equally committed to the region. The Carter Center and Emory University recruited Robert Pastor to be director of our Latin American and Caribbean Program (LACP). He served as my national security advisor for Latin American and Caribbean Affairs when I was president and has been the principal advisor on the region to Rosalynn and me ever since. An Emory professor and author of 10 books and hundreds of articles on U.S. -

The Studio System and Conglomerate Hollywood

TCHC01 6/22/07 02:16 PM Page 11 PART I THE STRUCTURE OF THE INDUSTRY TCHC01 6/22/07 02:16 PM Page 12 TCHC01 6/22/07 02:16 PM Page 13 CHAPTER 1 THE STUDIO SYSTEM AND CONGLOMERATE HOLLYWOOD TOM SCHATZ Introduction In August 1995 Neal Gabler, an astute Hollywood observer, wrote an op-ed piece for The New York Times entitled “Revenge of the Studio System” in response to recent events that, in his view, signaled an industry-wide transformation (Gabler 1995). The previous year had seen the Seagram buyout of MCA-Universal, Time Warner’s purchase of the massive Turner Broadcasting System, and the launch of Dream- Works, the first new movie studio since the classical era. Then on August 1 came the bombshell that provoked Gabler’s editorial. Disney announced the acquisition of ABC and its parent conglomerate, Cap Cities, in a $19 billion deal – the second- largest merger in US history, which created the world’s largest media company. Disney CEO Michael Eisner also disclosed a quarter-billion-dollar deal with Mike Ovitz of Hollywood’s top talent agency, Creative Artists, to leave CAA and run the Disney empire. For Gabler, the Disney deals confirmed “a fundamental shift in the balance of power in Hollywood – really the third revolution in the relationship between industry forces.” Revolution I occurred nearly a century before with the formation of the Hollywood studios and the creation of a “system” that enabled them to con- trol the movie industry from the 1920s through the 1940s. Revolution II came with the postwar rise of television and the dismantling of the studio system by the courts, which allowed a new breed of talent brokers, “most notably Lew Wasserman of the Music Corporation of America [MCA],” to usurp control of the film industry.