Brahms, Robert Keller, and the Train Over the Brünig Pass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

Linthsicht 57 April20

NR. 57 / APRIL 2020 100 % Wirkung durch 100 % * Abdeckung *Amtliche Sendung in ALLE Haushaltungen LinthSichtAmtliche Mitteilungen aus Benken, Kaltbrunn, Schänis und Uznach BENKEN KALTBRUNN SCHÄNIS UZNACH «Vision Benken 2030» – Grosse Solidarität! Entlastung Verkehrs Ertragsüberschuss von Ein neues Leitbild knoten SäumergutFeld 1,54 Mio. Franken Seite 2 Seite 6 Seite 10 Seite 17 miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander mit einander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinan der miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander miteinander füreinanderCovid19: Hilfsmassnahmen miteinander in den füreinander Gemeinden miteinander füreinander miteinanderSolidarität füreinander und miteinanderUnterstützung füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander Seitenfüreinander 24 – 25 miteinander füreinander mit einander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinan der miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander mit einander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinan der miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander miteinander füreinander -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

Unc Symphony Orchestra Library

UNC ORCHESTRA LIBRARY HOLDINGS Anderson Fiddle-Faddle Anderson The Penny-Whistle Song Anderson Plink, Plank, Plunk! Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby Arensky Silhouettes, Op. 23 Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky, Op. 35a Bach, J.C. Domine ad adjuvandum Bach, J.C. Laudate pueri Bach Cantata No. 106, “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” Bach Cantata No. 140, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” Bach Cantata No. 209, “Non sa che sia dolore” Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058 Bach Concerto No. 1 in C minor for Two Claviers, BWV 1060 Bach Concerto No. 2 in C major for Three Claviers, BWV 1064 Bach Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, BWV 1041 Bach Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 Bach Komm, süsser Tod Bach Magnificat in D major, BWV 243 Bach A Mighty Fortress Is Our God Bach O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 Bach Prelude, Choral and Fugue Bach Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Bach Suite in B minor Bach Adagio from Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Barber Adagio for Strings, Op. -

Gemeinde Schänis Nr

Schänis Herausgeber: Gemeinde Schänis Nr. 30 Dezember 2008 Als Knecht und Magd zusammengefunden Am 13. November durften Josef und Elsa Steiner-Aebli ihre Diamantene Hochzeit feiern. 60 Jahre Freud und Leid gemeinsam getragen – ein solch einmaliges Jubiläum darf gebührend gefeiert werden. Schänis ist nicht China Von Irene Riget-Rüttimann «Manchmal möchte ich ein Chinese sein. Vorzugsweise Bürgermeister Zu Besuch beim Jubilarenpaar in der Untermatt, ein Ja-Wort in der Klosterkirche von Schanghai oder Kanton.» So habe ich schon gedacht; und zwar trister Novembertag, die leise tickende Wanduhr ver- ganz klar nicht aus Eitelkeit oder Grössenwahnsinn. Sondern wenn strömt Gemütlichkeit in der warmen Stube. Gerahmte Am 13. November vor 60 Jahren war es also, als sich ich im Fernsehen mitansehen konnte oder musste, wie rasch dort Bilder auf dem Stubenbuffet zeigen pausbäckige Gross- die beiden das Ja-Wort in der Klosterkirche in Ein- Städte wachsen, wie in kürzester Zeit die grössten Hochhäuser zum kinder und glückliche junge Menschen. Bilder, die siedeln gaben. «Mir händ en eifachs Hochzig gha», Himmel gezogen werden. an Geburten, Hochzeiten und Familienfeste erinnern. erinnert sich Elsa, welche für jene Zeit üblich in Und ich in Schänis habe den Stein des Sisyphus zur Federi zu rollen, Gründe zum Feiern gab es in der Kürze einige bei schwarz heiratete. Zu fünft reiste das Brautpaar mit unentwegt und immer wieder. Statt grosse Würfe zu machen, habe Steiners, genannt ‹Untermättlers›. Im Laufe des Jahres einem Chauffeur ins Klosterdorf. Als Trauzeugen ich mich mit mühsamen Kleinigkeiten abzuplagen: Mit unerlaubten wurden die beiden Urgrosskinder Marina und Nicole standen ihnen Josef’s jüngerer Bruder Fredi sowie Auffüllungen, widerrechtlich erstellten Bauten und falsch bewirt- geboren, was den Jubilaren eine besondere Freude ist. -

Charles Villiers Stanford's Experiences with and Contributions

Charles Villiers Stanford’s Experiences with and contributions to the solo piano repertoire Adèle Commins Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) has long been considered as one of the leaders of the English Musical Renaissance on account of his work as composer, conductor and pedagogue. In his earlier years he rose to fame as a piano soloist, having been introduced to the instrument at a very young age. It is no surprise then that his first attempts at composition included a march for piano in i860.1 The piano continued to play an important role in Stanford’s compositional career and his last piano work, Three Fancies, is dated 1923. With over thirty works for the instrument, not counting his piano duets, Stanford’s piano pieces can be broadly placed in three categories: (i) piano miniatures or character pieces which are in the tradition of salon or domestic music; (ii) works which have a pedagogical function; and (iii) works which are written in a more virtuosic vein. In each of these categories many of the works remain unpublished. In most cases the piano scores are not available for purchase and this has hindered performances after his death.2 The repertoire of pianists should not be limited to the music of European composers and publishers, like performers, are responsible for the exposure a composer’s works receives. New editions of Stanford’s piano music need to be created and published in order to raise awareness of the richness of Stanford’s contribution to piano literature. While there has been renewed interest in the composer’s life and music by musicologists and performers — primarily initiated by the recent Stanford biographies in 2002 by Dibble and Rodmell — the 1 Originally termed Opus 1 in Stanford’s sketch book it was reproduced in Anon., ‘Charles Villiers Stanford’, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 39 670 (1898), 785-793 (p. -

The First Piano Concerto of Johannes Brahms: Its History and Performance Practice

THE FIRST PIANO CONCERTO OF JOHANNES BRAHMS: ITS HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Mark Livshits Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Joyce Lindorff, Advisory Chair, Keyboard Studies Dr. Charles Abramovic, Keyboard Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Maurice Wright, External Member, Temple University, Music Studies ABSTRACT In recent years, Brahms’s music has begun to occupy a larger role in the consciousness of musicologists, and with this surge of interest came a refreshingly original approach to his music. Although the First Piano Concerto op. 15 of Johannes Brahms is a beloved part of the standard piano repertoire, there is a curious under- representation of the work through the lens of historical performance practice. This monograph addresses the various aspects that comprise a thorough performance practice analysis of the concerto. These include pedaling, articulation, phrasing, and questions of tempo, an element that takes on greater importance beyond just complicating matters technically. These elements are then put into the context of Brahms’s own pianism, conducting, teaching, and musicological endeavors based on first and second-hand accounts of the composer’s work. It is the combining of these concepts that serves to illuminate the concerto in a far more detailed fashion, and ultimately enabling us to re-evaluate whether the time honored modern interpretations of the work fall within the boundaries that Brahms himself would have considered effective and accurate. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my committee and Dr. -

Rangliste 300M

Regionalschützenverein See - Gaster www.rsv-see-gaster.ch Rangliste Feldschiessen 2016 300m rang namen vorname geboren kurz sektionsname waffe resultat 1 Thoma Karl 22.05.1948 V Amden Mattstockschützen Stgw 57 72 2 Gmür Peter 05.02.1974 A Amden Mattstockschützen Stgw 57 72 3 Widmer Marc 11.06.1983 A Schmerikon SV Stgw 90 71 4 Rüdisüli Anita 06.10.1997 J Benken SG Stgw 90 70 5 Stoob Hans 23.10.1959 A Gommiswald SV Stgw 57 70 6 Hämmerli Peter 04.10.1965 A Weesen SV Stgw 57 70 7 Blöchlinger Thomas 02.01.1970 A Gommiswald SV Stgw 90 70 8 Müller Ruedi 11.03.1981 A Eschenbach-Neuhaus SG Stgw 90 70 9 Schuppli Pascal 01.01.1999 J Rufi-Maseltrangen MSV Stgw 90 69 10 Bachmann Ramona 21.03.1998 J Weesen SV Stgw 90 69 11 Trümpi Jakob 18.05.1934 SV Rapperswil Stadtschützen Stgw 57 69 12 Gmür Beni 06.03.1958 A Amden SG Churfirsten Stgw 57 69 13 Duft Marcel 01.01.1960 A Rufi-Maseltrangen MSV Stgw 90 69 14 Rüegg Heiri 20.03.1961 A Walde-St.Gallenkappel SV Stgw 57 69 15 Raymann Hubert 11.10.1961 A Walde-St.Gallenkappel SV Stgw 57 69 16 Müller Marcel 01.09.1962 A Uznach SV Stgw 90 69 17 Sennhauser Beat 30.06.1970 A Ricken SG Stgw 57 69 18 Bachmann Peter 03.03.1977 A Amden Mattstockschützen Stgw 90 69 19 Gmür Ivo 01.08.1980 A Amden SG Churfirsten Stgw 90 69 20 Gmür Reto 05.04.1981 A Amden Mattstockschützen Stgw 57 69 21 Bischof Marco 20.09.1988 A Amden Mattstockschützen Stgw 90 69 22 Egli Adrian 01.01.1995 A Rufi-Maseltrangen MSV Stgw 90 69 23 Meile Thomas 01.01.1945 SV Uznach SV Stgw 90 68 24 Drexel Bruno 24.01.1948 V Kaltbrunn FSG Stgw 57 68 25 Thoma -

Performances from 1974 to 2020

Performances from 1974 to 2020 2019-20 December 1 & 2, 2018 Michael Slon, Conductor September 28 & 29, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor MOZART Symphony No. 32 February 16 & 17, 2019 ROUSTOM Ramal Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major November 16 & 17, 2019 MOYA Siempre Lunes, Siempre Marzo Benjamin Rous & Michael Slon, Conductors KODALY Variations on a HunGarian FolksonG MONTGOMERY Caught by the Wind ‘The Peacock’ RICHARD STRAUSS Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major March 23 & 24, 2019 MENDELSSOHN Psalm 42 Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRUCKNER Te Deum in C Major BARTOK Violin Concerto No. 2 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major December 6 & 7, 2019 Michael Slon, Conductor April 27 & 28, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor WAGNER Prelude from Parsifal February 15 & 16, 2020 SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A minor Benjamin Rous, Conductor SHATIN PipinG the Earth BUTTERWORTH A Shropshire Lad RESPIGHI Pines of Rome BRITTEN Nocturne GRACE WILLIAMS Elegy for String Orchestra June 1, 2019 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS On Wenlock Edge Benjamin Rous, Conductor ARNOLD Tam o’Shanter Overture Pops at the Paramount 2018-19 2017-18 September 29 & 30, 2018 September 23 & 24, 2017 Benjamin Rous, Conductor Benjamin Rous, Conductor BOWEN Concerto in C minor for Viola WALKER Lyric for StrinGs and Orchestra ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine MUSGRAVE SonG of the Enchanter MOZART Clarinet Concerto in A Major SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D Major BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major November 17 & 18, 2018 October 6, 2017 Damon Gupton, Conductor Michael Slon, Conductor ROSSINI Overture to Semiramide UVA Bicentennial Celebration BARBER Violin Concerto WALKER Lyric for StrinGs TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. -

Program Notes by Dr

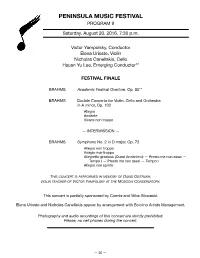

PENINSULA MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM 9 Saturday, August 20, 2016, 7:30 p.m. Victor Yampolsky, Conductor Elena Urioste, Violin Nicholas Canellakis, Cello Hsuan Yu Lee, Emerging Conductor** FESTIVAL FINALE BRAHMS Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80** BRAHMS Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 102 Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo — INTERMISSION — BRAHMS Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso (Quasi Andantino) — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I — Presto ma non assai — Tempo I Allegro con spirito THIS CONCERT IS PERFORMED IN MEMORY OF DAVID OISTRAKH, VIOLIN TEACHER OF VICTOR YAMPOLSKY AT THE MOSCOW CONSERVATORY. This concert is partially sponsored by Connie and Mike Glowacki. Elena Urioste and Nicholas Canellakis appear by arrangement with Sciolino Artists Management. Photography and audio recordings of this concert are strictly prohibited. Please, no cell phones during the concert. — 30 — PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra in A Program 9 minor, Op. 102 JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) Composed in 1887. Premiered on October 18, 1887 in Cologne, with Joseph Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Joachim and Robert Hausmann as soloists and the com- poser conducting. Composed in 1880. Premiered on January 4, 1881 in Breslau, conducted by Johannes Brahms first met the violinist Joseph the composer. Joachim in 1853. They became close friends and musi- cal allies — the Violin Concerto was not only written Artis musicae severioris in Germania nunc princeps for Joachim in 1878 but also benefited from his careful — “Now the leader in Germany of music of the more advice in many matters of string technique. -

Adelrich Steinach's Swiss Colonists: an Introduction

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 40 Number 2 Article 3 6-2004 Adelrich Steinach's Swiss Colonists: An Introduction Urspeter Schelbert Ph.D. Walchwil, Canton Zug Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Schelbert, Urspeter Ph.D. (2004) "Adelrich Steinach's Swiss Colonists: An Introduction," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 40 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol40/iss2/3 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Schelbert: Adelrich Steinach's Swiss Colonists: An Introduction ADELRICH STEINACH' S SWISS COLONISTS: AN INTRODUCTION Among the millions of immigrants to the United States the Swiss constitute only a small group. Their involvement in the emergence of the United States to date has been portrayed only selectively or in relatively brief encyclopedic entries. 1 But a vast number of essays and books on individual men and women, families, and settlements do exist.2 The book Geschichte und Leben der Schweizer Kolonien in den Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika, however, compiled in the 1880s in collaboration with the North American Griitli-Bundby the Swiss physician Adelrich Steinach residing in New York City, is an early attempt at presenting an overview of the involvement of Swiss in the history of the United States.