The First Piano Concerto of Johannes Brahms: Its History and Performance Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6

Concert Program V: Alla Zingarese August 5 and 6 Friday, August 5 F RANZ JOSEph HAYDN (1732–1809) 8:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Rondo all’ongarese (Gypsy Rondo) from Piano Trio in G Major, Hob. XV: 25 (1795) S Jon Kimura Parker, piano; Elmar Oliveira, violin; David Finckel, cello Saturday, August 6 8:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton HErmaNN SchULENBURG (1886–1959) AM Puszta-Märchen (Gypsy Romance and Czardas) (1936) PROgram OVERVIEW CharlES ROBERT VALDEZ A lifelong fascination with popular music of all kinds—espe- Serenade du Tzigane (Gypsy Serenade) cially the Gypsy folk music that Hungarian refugees brought to Germany in the 1840s—resulted in some of Brahms’s most ANONYMOUS cap tivating works. The music Brahms composed alla zinga- The Canary rese—in the Gypsy style—constitutes a vital dimension of his Wu Han, piano; Paul Neubauer, viola creative identity. Concert Program V surrounds Brahms’s lusty Hungarian Dances with other examples of compos- JOHANNES BrahmS (1833–1897) PROGR ERT ers drawing from Eastern European folk idioms, including Selected Hungarian Dances, WoO 1, Book 1 (1868–1869) C Hungarian Dance no. 1 in g minor; Hungarian Dance no. 6 in D-flat Major; the famous rondo “in the Gypsy style” from Joseph Haydn’s Hungarian Dance no. 5 in f-sharp minor G Major Piano Trio; the Slavonic Dances of Brahms’s pro- Wu Han, Jon Kimura Parker, piano ON tégé Antonín Dvorˇák; and Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane, a paean C to the Hun garian violin virtuoso Jelly d’Arányi. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Late Romantic Period 1850-1910 • Characteristics of Romantic Period

Late Romantic Period 1850-1910 • Characteristics of Romantic Period o Emotion design over intellectual design o Individual over society o Music increased in length and changed emotion often in the same piece • Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) o French composer o Known for writing for large orchestras, sometimes over 1000 musicians o An Episode in the Life of an Artist (Symphonie Fantastique) • Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow. • Richard Wagner (1813-1883) o German composer and theatre director o Known for opera – big dramatic works • Built his own opera house in order to be able to accommodate his works • Subjects drawn from Norse mythology o Lohengrin – Bridal Chorus o Die Walkure • Franz Liszt (1811-1886) o Hungarian composer and virtuoso pianist o Used gypsy music as basis for compositions o Created modern piano playing technique o Invented the form of Symphonic Poem or Tone Poem Music based on art, literature, or other “nonmusical” idea One movement with several ‘ideas’ that move freely throughout the piece o Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Brahms, Johannes (B Hamburg, 7 May 1833; D Vienna, 3 April 1897)

Brahms, Johannes (b Hamburg, 7 May 1833; d Vienna, 3 April 1897). German composer. The successor to Beethoven and Schubert in the larger forms of chamber and orchestral music, to Schubert and Schumann in the miniature forms of piano pieces and songs, and to the Renaissance and Baroque polyphonists in choral music, Brahms creatively synthesized the practices of three centuries with folk and dance idioms and with the language of mid and late 19thcentury art music. His works of controlled passion, deemed reactionary and epigonal by some, progressive by others, became well accepted in his lifetime. 1. Formative years. 2. New paths. 3. First maturity. 4. At the summit. 5. Final years and legacy. 6. Influence and reception. 7. Piano and organ music. 8. Chamber music. 9. Orchestral works and concertos. 10. Choral works. 11. Lieder and solo vocal ensembles. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GEORGE S. BOZARTH (1–5, 10–11, worklist, bibliography), WALTER FRISCH (6– 9, 10, worklist, bibliography) Brahms, Johannes 1. Formative years. Brahms was the second child and first son of Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen (1789–1865) and Johann Jakob Brahms (1806–72). His mother, an intelligent and thrifty woman simply educated, was a skilled seamstress descended from a respectable bourgeois family. His father came from yeoman and artisan stock that originated in lower Saxony and resided in Holstein from the mid18th century. A resourceful musician of modest talent, Johann Jakob learnt to play several instruments, including the flute, horn, violin and double bass, and in 1826 moved to the free Hanseatic port of Hamburg, where he earned his living playing in dance halls and taverns. -

The Lied of Five German Composers.Pdf

The Lied of Five German Composers A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Music Department of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts by Whitney Laine Westbrook June 2010 © 2010 Whitney Laine Westbrook The Lied of Five German Composers: List of Repertoire 1. “Fussreise” (2:54)…...………………………………..Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) 2. “Sapphische Ode” (2:30)………………………Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 3. “Urlicht” (5:13)...…………………………………Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) 4. “Erhebung”(1:13)............................................Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) 5. “Morgen” (3:50).………………………………...Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Fussreise Hugo Filipp Jakob Wolf, born on March 13, 1860, in modern day Yugoslavia, experienced an early musical upbringing under the guidance of his father and later on studied with his local school teacher, Sebastian Weixler. Wolf displayed much musical promise, primarily within the realms of violin and piano. Although music exerted an influence over Wolf, school did not. Throughout his life, Wolf exercised a rebellion against many scholastic institutions, including the Conservatory of Vienna; this was his third school from which he withdrew. Having escaped school, Hugo Wolf attempted to make a living in many trades, including teaching piano and accompanying various other artists. Although he became a “Jack of All Trades,” a steady income was not reaching Wolf, and he continued on living in poverty. Wolf did excel as a music critic, a profession that did supply a small income and yet Wolf earned resentment from his musical colleagues. The harsh criticisms that flew from the quick-witted critic alienated certain musicians who in return refused Wolf any help. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

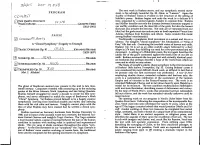

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

Charles Villiers Stanford's Experiences with and Contributions

Charles Villiers Stanford’s Experiences with and contributions to the solo piano repertoire Adèle Commins Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) has long been considered as one of the leaders of the English Musical Renaissance on account of his work as composer, conductor and pedagogue. In his earlier years he rose to fame as a piano soloist, having been introduced to the instrument at a very young age. It is no surprise then that his first attempts at composition included a march for piano in i860.1 The piano continued to play an important role in Stanford’s compositional career and his last piano work, Three Fancies, is dated 1923. With over thirty works for the instrument, not counting his piano duets, Stanford’s piano pieces can be broadly placed in three categories: (i) piano miniatures or character pieces which are in the tradition of salon or domestic music; (ii) works which have a pedagogical function; and (iii) works which are written in a more virtuosic vein. In each of these categories many of the works remain unpublished. In most cases the piano scores are not available for purchase and this has hindered performances after his death.2 The repertoire of pianists should not be limited to the music of European composers and publishers, like performers, are responsible for the exposure a composer’s works receives. New editions of Stanford’s piano music need to be created and published in order to raise awareness of the richness of Stanford’s contribution to piano literature. While there has been renewed interest in the composer’s life and music by musicologists and performers — primarily initiated by the recent Stanford biographies in 2002 by Dibble and Rodmell — the 1 Originally termed Opus 1 in Stanford’s sketch book it was reproduced in Anon., ‘Charles Villiers Stanford’, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 39 670 (1898), 785-793 (p. -

Unknown Brahms.’ We Hear None of His Celebrated Overtures, Concertos Or Symphonies

PROGRAM NOTES November 19 and 20, 2016 This weekend’s program might well be called ‘Unknown Brahms.’ We hear none of his celebrated overtures, concertos or symphonies. With the exception of the opening work, all the pieces are rarities on concert programs. Spanning Brahms’s youth through his early maturity, the music the Wichita Symphony performs this weekend broadens our knowledge and appreciation of this German Romantic genius. Hungarian Dance No. 6 Johannes Brahms Born in Hamburg, Germany May 7, 1833 in Hamburg, Germany Died April 3, 1897 in Vienna, Austria Last performed March 28/29, 1992 We don’t think of Brahms as a composer of pure entertainment music. He had as much gravitas as any 19th-century master and is widely regarded as a great champion of absolute music, music in its purest, most abstract form. Yet Brahms loved to quaff a stein or two of beer with friends and, within his circle, was treasured for his droll sense of humor. His Hungarian Dances are perhaps the finest examples of this side of his character: music for relaxation and diversion, intended to give pleasure to both performer and listener. Their music is familiar and beloved - better known to the general public than many of Brahms’s concert works. Thus it comes as a surprise to many listeners to learn that Brahms specifically denied authorship of their melodies. He looked upon these dances as arrangements, yet his own personality is so evident in them that they beg for consideration as original compositions. But if we deem them to be authentic Brahms, do we categorize them as music for one-piano four-hands, solo piano, or orchestra? Versions for all three exist in Brahms's hand. -

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger’s Requiems Katherine FitzGibbon Background: Historicism and German During the nineteenth century, German Requiems composers began creating alternative German Requiems that used either German literary material, as in Schumann’s Requiem für ermans have long perceived their Mignon with texts by Goethe, or German literary and musical traditions as being theology, as in selections from Luther’s of central importance to their sense of translation of the Bible in Brahms’s Ein Gnational identity. Historians and music scholars in deutsches Requiem. The musical sources tended the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be specifically German as well; composers sought to define specifically German attributes in made use of German folk materials, German music that elevated the status of German music, spiritual materials such as the Lutheran chorale, and of particular canonic composers. and historical forms and ideas like the fugue, the pedal point, antiphony, and other devices derived from Bach’s cantatas and Schütz’s funeral music. It was the Requiem that became an ideal vehicle for transmitting these German ideals. Although there had long been a tradition of As Daniel Beller-McKenna notes, Brahms’s Ein German Lutheran funeral music, it was only in deutsches Requiem was written at the same the nineteenth century that composers began time as Germany’s move toward unification creating alternatives to the Catholic Requiem under Kaiser Wilhelm and Bismarck. While with the same monumental scope (and the same Brahms exhibited some nationalist sympathies— title). Although there were several important he owned a bust of Bismarck and wrote the examples of Latin Requiems by composers like jingoistic Triumphlied—his Requiem became Mozart, none used the German language or the Lutheran theology that were of particular importance to the Prussians. -

The Oldest American Mennonite Church the Beginnings of Germantown

Published in the interest of the best in the religious, social, and economic phases of Mennonite culture To Our Readers WATCH YOUR EXPIRATION DATE! If your subscription expires with this issue you will find a notice to that effect enclosed, as well as a self-addressed envelope for your convenience in renewing your subscription. Note our special rates on the envelope. While you renew your subscription, why not take care of some Christmas shopping and add some subscriptions for friends and relatives? Note the special rates. Special rates apply only to orders sent in directly to Mennonite Life. Bound Volumes for Your Library or as Gifts Bound volumes of Mennonite Life are available as follows: 1. Volume I-III (1946-48).............................................................................. $6.00 2. Volume IV-V (1949-50)............................................................................. $5.00 3. Volume VI-VII (1951-52)............................. ............................................. $5.00 4. Volume VIII-IX (1953-54)........................................................................ $5.00 5. Volume X-XI (1955-56)............................................................................ $5.00 6. Volume XII-XIV (1957:58)......................................................................... $5.00 If ordered directly from Mennonite Life all six volumes are available at $27.50. Subscription rates are: 1 year—$2.00; 2 years—-$3.50; 3 years—$5.00; 5 years—$8.00. Special Issues Readers of Mennonite Life will recall that some issues have been devoted to special sub jects, such as "Peacetime Alternative Service” or the "1-W Program.’.’ The July, 1958, issue was devoted to this program. It also contained four articles on music and organs. This issue is par ticularly helpful for study groups, Sunday evening programs, and 1-W orientation sessions. Single copies of Mennonite Life cost fifty cents.