Brahms, Johannes (B Hamburg, 7 May 1833; D Vienna, 3 April 1897)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brahms Horn Trio

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Student Recitals Concert and Recital Programs 11-23-2019 Brahms Horn Trio Chloë Sodonis Caroline Beckman Stephen Estep Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/student_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons This Program is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Recitals by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chloë Sodonis is a junior French horn performance major at Cedarville University. She is principal horn in the University Wind Symphony and Orchestra as well as an active member in the broader south Ohio music community, performing as a substitute musician for the Kettering Praise Orchestra, Dayton Philharmonic Concert Band, and Springfield Symphony Orchestra. She loves chamber music and has experience playing in brass quintets, woodwind quintets, a horn choir, a horn quartet, a horn and harp duet, and an oboe trio. Chloë has thoroughly enjoyed preparing this trio for horn, violin and piano, and she loves the range of emotions evoked through this piece. She hopes to continue her studies in graduate school and earn a position as a member of an esteemed symphony orchestra. Caroline Beckman, a Kansas native, is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Music with concentrations in violin performance and piano pedagogy at Cedarville University, where she serves as a concertmaster of the Cedarville University Orchestra. Beginning formal music instruction at age six, Caroline went on to win numerous awards in piano and violin at State KMTA and KMFA competitions, the Bethany Oratorio Society Festival Apprenticeship Chair, and 2015 Salina Youth Symphony Concerto Competition. -

Journal of Romanian Literary Studies Issue No

2013 Journal of Romanian Literary Studies Issue no. 3 http://www.upm.ro/jrls/ E-ISSN: 2248-3304 Published by Petru Maior University Press, Nicolae Iorga Street No. 1, 540088, Târgu-Mureș, Romania Email: [email protected]; (c) 2011-2013 Petru Maior University of Târgu-Mureș SCIENTIFIC BOARD: Prof. Virgil NEMOIANU, PhD Prof. Nicolae BALOTĂ, PhD Prof. Nicolae MANOLESCU, PhD Prof. Eugen SIMION, PhD Prof. George BANU, PhD Prof. Alexandru NICULESCU, PhD EDITORIAL BOARD: Editorial Manager: Prof. Iulian BOLDEA, PhD Executive Editor: Prof. Al. CISTELECAN, PhD Editors: Prof. Cornel MORARU, PhD Prof. Andrei Bodiu, PhD Prof. Mircea A. DIACONU, PhD Assoc. Prof. DORIN STEFANESCU, PhD Assoc. Prof. Luminița CHIOREAN, PhD Lecturer Dumitru-Mircea BUDA, PhD CONTACT: [email protected], [email protected] Table of Contents AL. CISTELECAN Faith Testimonials ...................................................................................................................... 3 ȘTEFAN BORBELY The Literary Pursuit of a Historian of Religions: The Case of Ioan Petru Culianu ................ 13 CAIUS DOBRESCU Sphinx Riddles for Zamolxes. Ethno-Politics, Archaic Mythologies and Progressive Rock in Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania ................................................................................................. 21 MIRCEA A. DIACONU The Critical Spirit in ”România Literară” in 1989 ................................................................. 31 LIVIU MALIȚA 1918: One Nation and Two Memories .................................................................................... -

Programme Notes by Chris Darwin. Use Freely for Non-Commercial Purposes Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Horn Trio in E Op 40 (1865)

Programme notes by Chris Darwin. Use freely for non-commercial purposes Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Horn Trio in E♭ Op 40 (1865) Andante Scherzo (Allegro) Adagio mesto Allegro con brio For Brahms the early 1860s were a productive time for chamber music: 2 string sextets, 2 piano quartets, a piano quintet and a cello sonata as well as this horn trio. As a child Brahms learned piano, cello and natural horn, so perhaps this work, written shortly after the death of his mother, involved the instruments of his youth (he specified that the horn part could be played by the cello). The quality of the notes produced by hand-stopping a natural horn are significantly different from those of a valve horn, and Brahms exploits these particular qualities in the piece. The overall structure of the work is unusual for Brahms since it echoes the old Church Sonata (Sonata di Chiesa) – a form much used by Corelli, with four movements alternating slow-fast-slow-fast. The first movement in turn alternates a broad, nostalgically tender Andante with a more animated section. The opening theme, though introduced by the violin (illustrated) is well-suited to the natural horn, which repeats it and later re-introduces it when the Andante section returns twice more. The rhythmically complex Scherzo leads to the emotional heart of the work, the Adagio mesto. Dark colours from the piano in the 6 flats of Eb minor, make even more sad a theme of mournful semitones to make a movement of great intensity. But, with the end of the movement, mourning passes and we can move on to the Finale. -

Spring Concert Calendar

SPRING CONCERT CALENDAR March 2019 Tuesday, April 16 | 12:30 p.m. Kim Cook, Cello; Carl Blake, Piano Tuesday, March 5 | 12:30 p.m. L. V. Beethoven: Sonatas for Cello and Piano Hope Briggs, Soprano • No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 5 Shawnette Sulker, Soprano • No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102 Carl Blake, Piano Music written by Amy Beach; Jacqueline Hairston; Tuesday, April 23 | 12:30 p.m. Margaret Bonds; Lena McLin; William Grant Still; Hall Mana Trio Johnson; Robert L. Morris • Johannes Brahms: Horn Trio in E-flat Major, Op. 40 • Johann Joachim Quantz: Sonata in C Minor Tuesday, March 12 | 12:30 p.m. • Jean Baptiste Singelée: Duo Concertante, Op. 55 Paul Galbraith, 8-string Guitar • J. S. Bach: French Suite No.2 in C Minor, BWV 813 Tuesday, April 30 | 12:30 p.m. • Alexander Scriabin: Six Preludes Trio Continentale • W. A. Mozart: Allemande, from • Amy Beach: Op. 150, Trio., 3 Baroque Suite, K. 399 • Clara Schumann: Trio in G Minor, Op. 17, 3 • W. A. Mozart: Piano Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 570 • Rebecca Clarke: Viola Sonata,1 • Fanny Mendelssohn: Op. 11, 1 Tuesday, March 19 | 12:30 p.m. • Emilie Mayer, Noturno Cristiana Pegoraro, Piano • Lili Boulanger: D’un Matin de Printemps • Rossini/Pegoraro: Overture to Il • Jennifer Higdon: Piano Trio “Pale Yellow” Barbiere di Siviglia • Cecil Chaminade: Trio No. 2 in A Minor, 3 • Pegoraro: Colors of Love • Bizet/Pegoraro: Carmen Fantasy May 2019 • Pegoraro: The Wind and the Sea • Pegoraro/Porzio: Fantasia Italiana Tuesday, May 7 | 12:30 p.m. -

The Artistic Merits of Incorporating Natural Horn Techniques Into Valve Horn Performance

The Artistic Merits of Incorporating Natural Horn Techniques into Valve Horn Performance A Portfolio of Recorded Performances and Exegesis Adam Greaves Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide March 2012 i Table of Contents Abstract i Declaration ii Acknowledgements iii List of Figures iv Recital Programmes 1 Exegesis Introduction 2 Recital One 4 Recital two 11 Conclusion 25 Appendix: Concert Programmes Recital One 26 Recital Two 30 Bibliography 34 Recordings Recital One Recital Two ii Abstract The dissertation addresses the significance of how a command of the natural horn can aid performance on its modern, valve counterpart. Building on research already conducted on the topic, the practice-led project assesses the artistic merits of utilising natural horn techniques in performances on the valve horn. The exegesis analyses aesthetic decisions made in the recitals – here disposed as two CD recordings – and assesses the necessity or otherwise of valve horn players developing a command of the natural horn. The first recital comprises a comparison of performances by the candidate of Brahms’ Horn Trio, Op.40 (1865) on the natural and valve horns. The exegesis evaluates the two performances from an aesthetic and technical standpoint. The second recital, while predominantly performed on the valve horn, contains compositions that have been written with elements of natural horn technique taken into consideration. It also contains two pieces commissioned for this project, one by a student composer and the other by a professional horn player. These two commissions are offered as case studies in the incorporation of natural horn techniques into compositional praxis. -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

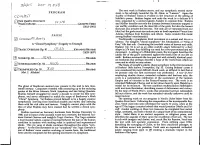

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: a Study of the Late Songs

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Casey-Ann Crutcher [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Crutcher, Natilan Casey-Ann, "Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3886. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3886 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Crutcher Dissertation submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In Voice Performance Hope Koehler, DMA, Chair Evan MacCarthy, Ph.D. William Koehler, DMA David Taddie, Ph.D. General Hambrick, BFA School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2019 Keywords: Johannes Brahms, Lieder, Late Style Copyright 2019 Natilan Crutcher Abstract Defining the Late Style of Johannes Brahms: A Study of the Late Songs Natilan Crutcher Johannes Brahms has long been viewed as a central figure in the Classical tradition during a period when the standards of this tradition were being altered and abandoned. -

Complete Piano Music • 2 Goran Filipec

includes WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS BERSA COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC • 2 TEMA CON VARIAZIONI BALLADE IN D MINOR SONATA IN C MAJOR RONDO-POLONAISE WALTZES GORAN FILIPEC BLAGOJE BERSA © Croatian Institute of Music / Hrvatski glazbeni zavodi GORAN FILIPEC BLAGOJE BERSA (1873–1934) Goran Filipec, laureate of the Grand Prix du Disque of the Ferenc Liszt Society of Budapest for his 2016 COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC • 2 recording of Liszt’s Paganini Studies (Naxos 8.573458), was born in Rijeka (Croatia) in 1981. He studied at the TEMA CON VARIAZIONI • BALLADE IN D MINOR Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, the Royal SONATA IN C MAJOR • RONDO-POLONAISE Conservatory in The Hague, the Hochschule für Musik WALTZES in Cologne and the Zagreb Academy of Music. He is a prize winner of several piano competitions including GORAN FILIPEC, Piano the Premio Mario Zanfi ‘Franz Liszt’, Concurso de Parnassos, the José Iturbi International Music Competition and the Gabala International Piano Catalogue Number: GP832 Competition. Filipec performs regularly in Europe, the Recording Dates: 15–16 October 2019 Recording Venue: Fazioli Concert Hall, Sacile, Italy United States, South America and Japan. He made his Producer: Goran Filipec © Stephany Stefan debut at Carnegie Hall in 2006, followed by Engineer: Matteo Costa performances in venues including the Mariinsky Editors: Goran Filipec, Matteo Costa Theatre, the Auditorium di Milano, Minato Mirai Hall, the Philharmonie de Paris and Piano: Fazioli, model F278 the Palace of Arts in Budapest. With the award by the Liszt Society, Goran Filipec Booklet Notes: Goran Filipec German Translation: Cris Posslac joined the list of prestigious laureates of the Grand Prix such as Vladimir Horowitz, Publisher: Croatian Institute of Music György Cziffra, Alfred Brendel, Claudio Arrau, Zoltán Kocsis and Maurizio Pollini. -

Schubert's Winterreise in Nineteenth-Century Concerts

Detours on a Winter’s Journey: Schubert’s Winterreise in Nineteenth-Century Concerts NATASHA LOGES Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/jams/article-pdf/74/1/1/465161/jams_74_1_1.pdf by American Musicological Society Membership Access user on 03 June 2021 Introduction For a time Schubert’s mood became more gloomy and he seemed upset. When I asked him what was the matter he merely said to me “Well, you will soon hear it and understand.” One day he said to me “Come to Schober’s to-day, I will sing you a cycle of awe-inspiring songs. I am anxious to know what you will say about them. They have affected me more than has been the case with any other songs.” So, in a voice wrought with emotion, he sang the whole of the “Winterreise” through to us.1 In 1858, Schubert’s friend Josef von Spaun published a memoir of Schubert that included this recollection of the composer’s own performance of his Winterreise,D.911.Spaun’s poignant account is quoted in nearly every pro- gram and recording liner note for the work, and many assume that he meant all twenty-four songs in the cycle, roughly seventy-five uninterrupted minutes of music, presented to a rapt, silent audience—in other words, a standard, modern performance.2 Spaun’s emotive recollection raises many questions, however. The first concerns what Spaun meant by “the whole of the ‘Winter- reise,’” and this depends on the date of this performance, which cannot be established. As many scholars have observed, Schubert most likely sang only the twelve songs he had initially composed.3 Susan Youens recounts that the 1. -

The First Piano Concerto of Johannes Brahms: Its History and Performance Practice

THE FIRST PIANO CONCERTO OF JOHANNES BRAHMS: ITS HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS by Mark Livshits Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Joyce Lindorff, Advisory Chair, Keyboard Studies Dr. Charles Abramovic, Keyboard Studies Dr. Michael Klein, Music Studies Dr. Maurice Wright, External Member, Temple University, Music Studies ABSTRACT In recent years, Brahms’s music has begun to occupy a larger role in the consciousness of musicologists, and with this surge of interest came a refreshingly original approach to his music. Although the First Piano Concerto op. 15 of Johannes Brahms is a beloved part of the standard piano repertoire, there is a curious under- representation of the work through the lens of historical performance practice. This monograph addresses the various aspects that comprise a thorough performance practice analysis of the concerto. These include pedaling, articulation, phrasing, and questions of tempo, an element that takes on greater importance beyond just complicating matters technically. These elements are then put into the context of Brahms’s own pianism, conducting, teaching, and musicological endeavors based on first and second-hand accounts of the composer’s work. It is the combining of these concepts that serves to illuminate the concerto in a far more detailed fashion, and ultimately enabling us to re-evaluate whether the time honored modern interpretations of the work fall within the boundaries that Brahms himself would have considered effective and accurate. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my committee and Dr. -

Jahresbericht 2010

UNION DER DEUTSCHEN AKADEMIEN DER WISSENSCHAFTEN vertreten durch die Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz Musikwissenschaftliche Editionen JAHRESBERICHT 2010 Koordination: Dr. Gabriele Buschmeier © 2011 by Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz. Alle Rechte einschließlich des Rechts zur Vervielfältigung, zur Einspeisung in elektronische Systeme sowie der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Jede Verwertung außer- halb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne ausdrückliche Geneh- migung der Akademie unzulässig und strafbar. Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, chlorfrei gebleichtem Papier. Druck: Rheinhessische Druckwerkstätte, Alzey Printed in Germany UNION DER DEUTSCHEN AKADEMIEN DER WISSENSCHAFTEN vertreten durch die Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz Musikwissenschaftliche Editionen JAHRESBERICHT 2010 1. Koordinierung der musikwissenschaftlichen Vorhaben durch die Union der deutschen Akademien der Wissenschaften .......................................................................... 3 2. Berichte der einzelnen Projekte Johannes Brahms, Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke ........................................................... 5 Christoph Willibald Gluck, Sämtliche Werke ..................................................................... 12 Georg Friedrich Händel, Hallische Händel-Ausgabe .......................................................... 15 Joseph Haydn, Werke .......................................................................................................... 17 Felix Mendelssohn