Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historiography of Musical Historicism: the Case Of

A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of MUSIC by Shao Ying Ho, B.M. San Marcos, Texas May 2013 A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS Committee Members Approved: _____________________________ Kevin E. Mooney, Chair _____________________________ Nico Schüler _____________________________ John C. Schmidt Approved: ___________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Shao Ying Ho 2013 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work, I, Shao Ying Ho, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first and foremost gratitude is to Dr. Kevin Mooney, my committee chair and advisor. His invaluable guidance, stimulating comments, constructive criticism, and even the occasional chats, have played a huge part in the construction of this thesis. His selfless dedication, patience, and erudite knowledge continue to inspire and motivate me. I am immensely thankful to him for what I have become in these two years, both intellectually and as an individual. I am also very grateful to my committee members, Dr. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Brahms, Johannes (B Hamburg, 7 May 1833; D Vienna, 3 April 1897)

Brahms, Johannes (b Hamburg, 7 May 1833; d Vienna, 3 April 1897). German composer. The successor to Beethoven and Schubert in the larger forms of chamber and orchestral music, to Schubert and Schumann in the miniature forms of piano pieces and songs, and to the Renaissance and Baroque polyphonists in choral music, Brahms creatively synthesized the practices of three centuries with folk and dance idioms and with the language of mid and late 19thcentury art music. His works of controlled passion, deemed reactionary and epigonal by some, progressive by others, became well accepted in his lifetime. 1. Formative years. 2. New paths. 3. First maturity. 4. At the summit. 5. Final years and legacy. 6. Influence and reception. 7. Piano and organ music. 8. Chamber music. 9. Orchestral works and concertos. 10. Choral works. 11. Lieder and solo vocal ensembles. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GEORGE S. BOZARTH (1–5, 10–11, worklist, bibliography), WALTER FRISCH (6– 9, 10, worklist, bibliography) Brahms, Johannes 1. Formative years. Brahms was the second child and first son of Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen (1789–1865) and Johann Jakob Brahms (1806–72). His mother, an intelligent and thrifty woman simply educated, was a skilled seamstress descended from a respectable bourgeois family. His father came from yeoman and artisan stock that originated in lower Saxony and resided in Holstein from the mid18th century. A resourceful musician of modest talent, Johann Jakob learnt to play several instruments, including the flute, horn, violin and double bass, and in 1826 moved to the free Hanseatic port of Hamburg, where he earned his living playing in dance halls and taverns. -

University of Washington School of Music St. Mark's Cathedral

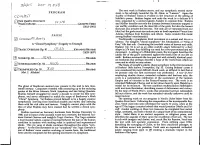

((J i\A~&!d C\I~ t \LqiJ }D10 I I . I'J. University of Washington School of Music in conjunction with St. Mark's Cathedral November 11-12, 2016 Dr. Carole Terry Wyatt Smith Co-Directors On behalfof the UW School of Music, I am delighted to welcome you to this very special Reger Symposium. Professor Carole Terry, working with her facuIty colleagues and students has planned an exciting program of recitals, lectures, and lively discussions that promise to illuminate the life and uniquely important music of Max Reger. I wish to thank all of those who are performing and presenting as well those who are attending and participating in other ways in our two-day Symposium. Richard Karpen Professor and Director School of Music, University ofWashington This year marks the lOOth anniversary of the death of Max Reger, a remarkable south German composer of works for organ and piano, as well as symphonic, chamber, and choral music. On November J ph we were pleased to present a group of stellar Seattle organists in a concert of well known organ works by Reger. On November 12, our Symposium includes a group of renowned scholars from the University of Washington and around the world. Dr. Christopher Anderson, Associate Professor of Sacred Music at Southern Methodist University, will present two lectures as a part of the Symposium: The first will be on modem performance practice of Reger's organ works, which will be followed later in the day with lecture highlighting selected chamber works. Dr. George Bozarth will present a lecture on some of Reger's early lieder. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Primary

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE PRIMARY RHETORIC AND THE STRUCTURE OF A PASSACAGLIA A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By SAMUEL R. BACKMAN Norman, Oklahoma 2020 PRIMARY RHETORIC AND THE STRUCTURE OF A PASSACAGLIA A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY A COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. John Schwandt, Chair Dr. Joyce Coleman Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Jennifer Saltzstein Dr. Jeffrey Swinkin © Copyright by SAMUEL RAY BACKMAN 2020 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my most sincere thanks to the following people: Dr. John Schwandt has broadened my perspective surrounding the pipe organ as a mechanism, as well as my understanding of its history and repertoire. Dr. Damin Spritzer, whose superb musicianship, laudable organ literature courses, and generous and congenial spirit allowed me to flourish during my studies. Furthermore her counsel was invaluable in creation of the present document. My committee members, Dr. Jennifer Saltzstein, Dr. Jeffrey Swinkin, Dr. Eugene Enrico, and Dr. Joyce Coleman, who selflessly devoted themselves to providing insightful, constructive, and timely feedback. I am honored to have had the opportunity to work with such fine scholars. Their invaluable insights had a profoundly positive impact on the quality, content, and focus of this document. My friends, family, and colleagues, who provided practical counsel and moral support throughout my years of study. My parents and sisters have been a robust and wonderful support system to me through all phases of life, and I am particularly grateful to my wife, Jessica, for her gracious support and patience. -

Calmus-Washington-Post Review April 2013.Pdf

to discover, nurture & promote young musicians Press: Calmus April 21, 2013 At Strathmore, Calmus Ensemble is stunning in its vocal variety, mastery By Robert Battey Last week, two of Germany’s best musical ensembles — one very large, one very small — visited our area. After the resplendence of the Dresden Staatskapelle on Tuesday at Strathmore, we were treated on Friday to an equally impressive display of precise, polished musicianship by the Calmus Ensemble, an a cappella vocal quintet from Leipzig. Founded in 1999 by students at the St. Thomas Church choir school (which used to be run by a fellow named Bach), Calmus presented a program both narrow and wide: all German works, but spanning more than four centuries of repertoire. The group held the audience at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria nearly spellbound with its artistry. The only possible quibble was that occasionally there was a very slight imbalance in the upper texture; Calmus has only one female member, the alto parts being taken by a countertenor who could not always match the clear projection of the soprano. But in matters of pitch, diction and musical shaping, I’ve never heard finer ensemble singing. From the lively “Italian Madrigals” of Heinrich Schütz, to a setting by Johann Hiller of “Alles Fleisch” (used by Brahms centuries later in “Ein Deutsches Requiem”), to the numinous coloratura of Bach’s “Lobet den Herrn,” to some especially lovely part-songs of Schumann, to a performance-art work written for the group by Bernd Franke in 2010, the quintet met the demands of every piece with cool perfection. -

Eftychia Papanikolaou Is Assistant Professor of Musicology and Coordinator of Music History Studies at Bowling Green State University in Ohio

Eftychia Papanikolaou is assistant professor of musicology and coordinator of music history studies at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Her research (from Haydn and Brahms to Mahler’s fi n-de-siècle Vienna), focuses on the in- terconnections of music, religion, and politics in the long nineteenth century, with emphasis on the sacred as a musical topos. She is currently completing a monograph on the genre of the Romantic Symphonic Mass <[email protected]>. famous poetic inter- it was there that the Requiem für Mignon polations from Johann (subsequently the second Abteilung, Op. The Wolfgang von Goethe’s 98b), received its premiere as an inde- Wilhelm Meisters Leh- pendent composition on November 21, rjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship], 1850. With this dramatic setting for solo especially the “Mignon” lieder, hold a voices, chorus, and orchestra Schumann’s prestigious place in nineteenth-century Wilhelm Meister project was completed. In lied literature. Mignon, the novel’s adoles- under 12 minutes, this “charming” piece, cent girl, possesses a strange personality as Clara Schumann put it in a letter, epito- whose mysterious traits will be discussed mizes Schumann’s predilection for music further later. Goethe included ten songs in that defi es generic classifi cation. This Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, eight of which article will consider the elevated status were fi rst set to music by Johann Fried- choral-orchestral compositions held in rich Reichardt (1752–1814) and were Schumann’s output and will shed light on included in the novel’s original publication tangential connections between the com- (1795–96). Four of those songs are sung poser’s musico-dramatic approach and his by the Harper, a character reminiscent of engagement with the German tradition. -

3982.Pdf (118.1Kb)

II 3/k·YC)) b,~ 1'1 ,~.>u The next work in Brahms oeuvre, and our symphonic second move . PROGRAM ment, is his achingly beautiful Op. 82, Niinie, or "Lament." Again the Ci) I~ /6':; / duality of Brahms vision is evident in the structure of the setting of Schiller's poem. Brahms begins and ends the work in a delicate 6/4 v time, separated by a central majestic Andante in common time. Brahms lD~B~=':~i.~.~~ f~.:..::.?.................... GIU~3-':;') and Schiller describe not only the distance between humanity trapped in ............. our earthly condition and the ideal life of the gods, but also the lament "" that pain also invades the heavens. Not only are we separated from our bliss, but the gods must also endure pain as death separated Venus from Adonis, Orpheus from Euridice, and others. Some consider this music PAUSE among Brahms' most beautiful. r;J ~ ~\.e;Vll> I Boe (5 Traditionally a symphonic third movement is a minuet and trio or a scherzo. For tonight's "choral symphony" the Schicksalslied, or "Song of A "Choral Symphony" -Tragedy to Triumph Fate," fills that role. Continuing the two-fold vision of heaven and earth, Brahms' Op. 54 is set as an other-worldly adagio followed by a fiery ~ TRAGIC OVERTURE Op. 81 .......... L~:.s..:>.................JOHANNES BRAHMS allegro in 3/4 time, thus fulfilling our need for a two-part minuet and trio (1833-1897) movement. A setting of a HOideriein poem, the text again describes the idyllic life of the god's contrasted against the fearful fate of our life on NANIE Op. -

Zur Reger-Rezeption Des Wiener Vereins Für Musikalische Privataufführungen

3 „in ausgezeichneten, gewissenhaften Vorbereitungen, mit vielen Proben“ Zur Reger-Rezeption des Wiener Vereins für musikalische Privataufführungen Mit Max Regers frühem Tod hatte der unermüdlichste Propagator seines Werks im Mai 1916 die Bühne verlassen. Sein Andenken in einer sich rasant verändernden Welt versuchte seine Witwe in den Sommern 1917, 1918 und 1920 abgehaltenen Reger-Festen in Jena zu wahren, während die schon im Juni 1916 gegründete Max- Reger-Gesellschaft (MRG) zwar Reger-Feste als Kern ihrer Aufgaben ansah, we- gen der schwierigen politischen und fnanziellen Lage aber nicht vor April 1922 ihr erstes Fest in Breslau veranstalten konnte. Eine kontinuierliche Auseinandersetzung zwischen diesen zwar hochkarätigen, jedoch nur sporadischen Initiativen bot Arnold Schönbergs Wiener „Verein für mu- sikalische Privataufführungen“, dessen Musiker, anders als die der Reger-Feste, in keinem persönlichen Verhältnis zum Komponisten gestanden hatten. Mit seinen idealistischen Zielen konnte der Verein zwar nur drei Jahre überleben, war aber in der kurzen Zeit seines Wirkens vom ersten Konzert am 29. Dezember 1918 bis zum letzten am 5. Dezember 1921 beeindruckend aktiv: In der ersten Saison veranstal- tete er 26, in der zweiten 35, in der dritten sogar 41 Konzerte, während die vorzeitig beendete vierte Saison nur noch elf Konzerte bringen konnte. Berücksichtigt wur- den laut Vereinsprospekt Werke aller Stilrichtungen unter dem obersten Kriterium einer eigenen Physiognomie ihres Schöpfers. Pädagogisches Ziel war es, das Pu- blikum auf -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano.