Beyond Beethoven LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano. -

Reger on the Web

28 reger on the web It is quite interesting to browse the internet regarding information on Max Reger, though it must be said that very few websites give really substantial accounts. Any account, however, can help retaining Reger under consideration. Several CD labels, concert organisers (http://www.chorkonzerte.de/ – Erlöserkirche München, http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/ Strasse/1945/WSB/reger.html – Washington Sängerbund, http://www.konzerte-weiden.de/ – Förderkreis für Kammermusik Weiden or http://www.max-reger-tage.de – Max-Reger-Tage Weiden) or music publishers (e.g. C. F. Peters, http://www.edition-peters.de/urtext/reger/ choralfantasien_2/) give tiny bits when advertising their stuff, and in music periodicals’ websi- tes reviews may be found (one of the best websites in this respect is http://www.gramopho- ne.co.uk/reviews/default.asp which stores past reviews of many Gramophone issues; other reviews can be found e. g. under http://www.musicweb.uk.net/). Links to commercial aspects of Reger – CDs, books, sheet music etc. can be found on http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/ reger.htm. There are several websites that are rather the only online source for one or the other spe- cific country, amongst them French, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, or Polish websites (http://mac-texier.ircam.fr/textes/c00002635/, http://www.rtve.es/rne/rc/boletin/boljun/reger.htm, http://members.tripod.lycos.co.kr/ksjpiano/reger.htm, http://www.ne.jp/asahi/piano/natsui/ S_Reger.htm – with reference to Reger’s Strauß transcription, http://wiem.onet.pl/ wiem/0039a5.html). Several Netherlands websites show how well-loved Reger is in our neigh- bouring country, and even deal with the interpretation of Reger’s organ music (http://www. -

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger’s Requiems Katherine FitzGibbon Background: Historicism and German During the nineteenth century, German Requiems composers began creating alternative German Requiems that used either German literary material, as in Schumann’s Requiem für ermans have long perceived their Mignon with texts by Goethe, or German literary and musical traditions as being theology, as in selections from Luther’s of central importance to their sense of translation of the Bible in Brahms’s Ein Gnational identity. Historians and music scholars in deutsches Requiem. The musical sources tended the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be specifically German as well; composers sought to define specifically German attributes in made use of German folk materials, German music that elevated the status of German music, spiritual materials such as the Lutheran chorale, and of particular canonic composers. and historical forms and ideas like the fugue, the pedal point, antiphony, and other devices derived from Bach’s cantatas and Schütz’s funeral music. It was the Requiem that became an ideal vehicle for transmitting these German ideals. Although there had long been a tradition of As Daniel Beller-McKenna notes, Brahms’s Ein German Lutheran funeral music, it was only in deutsches Requiem was written at the same the nineteenth century that composers began time as Germany’s move toward unification creating alternatives to the Catholic Requiem under Kaiser Wilhelm and Bismarck. While with the same monumental scope (and the same Brahms exhibited some nationalist sympathies— title). Although there were several important he owned a bust of Bismarck and wrote the examples of Latin Requiems by composers like jingoistic Triumphlied—his Requiem became Mozart, none used the German language or the Lutheran theology that were of particular importance to the Prussians. -

Max Reger Norrköping Symphony Orchestra Leif Segerstam

MAX REGER NORRKÖPING SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA LEIF SEGERSTAM LEIF SEGERSTAM BIS-9047 BIS-9047_f-b.indd 1 2013-10-17 11.46 REGER, Max (1873–1916) Orchestral Works Leif Segerstam conductor Norrköping Symphony Orchestra Total playing time: 3h 23m 54s 2 Disc 1 [64'56] Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Mozart 31'49 Op. 132 (1914) 1 Andante grazioso 2'29 2 Variation I. L’istesso tempo 2'35 3 Variation II. Poco agitato 1'52 4 Variation III. Con moto 1'21 5 Variation IV. Vivace 0'48 6 Variation V. Quasi presto 1'35 7 Variation VI. Sostenuto 2'20 8 Variation VII. Andante grazioso 2'20 9 Variation VIII. Molto sostenuto 7'13 10 Fugue. Allegretto grazioso 9'05 11 Symphonischer Prolog zu einer Tragödie 32'12 Op. 108 (1908) Grave – Allegro agitato – Molto sostenuto – Tempo I (Allegro) – Andante sostenuto – Tempo I (Allegro) – Molto sostenuto – Allegro agitato – Quasi largo – Andante sostenuto 3 Disc 2 [67'04] Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 114 (1910) 43'43 1 I. Allegro moderato 20'34 2 II. Largo con gran espressione 12'21 3 III. Allegretto con spirito 10'32 Love Derwinger piano Suite im alten Stil, Op. 93 (1906, orch. 1916) 22'21 4 I. Präludium. Allegro comodo 6'08 5 II. Largo. Largo 8'38 6 III. Fuge. Allegro con spirito, ma non troppo vivace – Meno mosso – Andante sostenuto – Quasi largo 7'25 Instrumentarium Grand Piano: Steinway D 4 Disc 3 [71'54] Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Beethoven 21'18 Op. 86 (1904, orch. -

Max Reger in Memoriam 100

MAX REGER IN MEMORIAM 100 SA 2. JULI 2016 KÖLN, TRINITATISKIRCHE 20.00 UHR SO 3. JULI 2016 ODENTHAL, ALTENBERGER DOM 14.30 UHR 2 PROGRAMM MAX REGER IN PROGRAMM MEMOR I A M 100 SA 2. JULI 2016 Max Reger Toccata und Fuge d-Moll op. 129,1 und 2 KÖLN, TRINITATISKIRCHE Toccata op. 80,11 Orgel 20.00 UHR Orgel aus: Drei Geistliche Gesänge op. 110 SO 3. JULI 2016 Choralkantate Nr. 4 Nr. 3 O Tod, wie bitter bist du ODENTHAL, ALTENBERGER DOM »Meinen Jesum lass ich nicht« WDR Rundfunkchor Köln 14.30 UHR Oratorienchöre Altenberger Dom Benedictus op. 59,9 Toccata d-Moll op. 59,5 Orgel Oratorienchöre Altenberger Dom Orgel Andreas Meisner Orgel und Leitung Choralkantate »Auferstanden, auferstanden« WDR Rundfunkchor Köln aus: Acht Geistliche Gesänge op. 138 für Alt, gemischten Chor und Orgel Hannes Reich Einstudierung Nr. 1 Der Mensch lebt und bestehet WoO V/4 Nr. 5 Stefan Parkman Einstudierung und Leitung Nr. 4 Unser lieben Frauen Traum Oratorienchöre Altenberger Dom WDR Rundfunkchor Köln WDR Rundfunkchor Köln Beate Koepp Alt aus: Drei sechsstimmige Chöre a cappella op. 39 KEINE PAUSE Nr. 3 Frühlingsblick WDR Rundfunkchor Köln SENDETERMIN WDR 3 FR 8. JULI 2016, 20.05 UHR Auf den Seiten des WDR Rundfunkchors unter wdr-rundfunkchor.de finden Sie fünf Tage vorher das Programmheft zum jeweiligen Konzert. HÖREN SIE DIESES KONZERT AUCH IM WDR 3 KONZERTPLAYER: WDR3.DE 4 5 MAX REGER IN MEMORIAM MAX REGER IN MEMORIAM MAX REGER IN MEMORIAM – EIN LEBEN ZWISCHEN PPP UND FFF Max Reger war ein Mensch ohne Maß – im Und auch die Grenzen der Konfessionen über- Arbeitsleben und auch privat. -

Programmheft Reger-Requiem 10,5Pt.Cdr

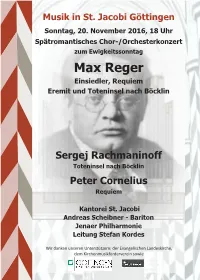

Musik in St. Jacobi Göttingen Sonntag, 20. November 2016, 18 Uhr Spätromantisches Chor-/Orchesterkonzert zum Ewigkeitssonntag Max Reger Einsiedler, Requiem Eremit und Toteninsel nach Böcklin Sergej Rachmaninoff Toteninsel nach Böcklin Peter Cornelius Requiem Kantorei St. Jacobi Andreas Scheibner - Bariton Jenaer Philharmonie Leitung Stefan Kordes Wir danken unseren Unterstützern: der Evangelischen Landeskirche, dem Kirchenmusikförderverein sowie PROGRAMM Max Reger (1873-1916) Die Toteninsel op. 128/3 (1912) aus „Vier Tondichtungen nach Arnold Böcklin” Max Reger Der Einsiedler op. 144a (1915) für Chor, Bariton und Orchester Sergej Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Die Toteninsel op. 29 (1909) nach Arnold Böcklin - Pause (ca. 15 min.) - Besichgen Sie in der Pause gerne unsere Ausstellung in den Seitenschiffen: „125 Jahre Kantorei St. Jacobi“ (Die Ausstellung ist noch bis zum 25.11. geöffnet.) Peter Cornelius (1824-1874) Requiem (1872) nach Hebbel Max Reger Der geigende Eremit op. 128/1 (1912) aus „Vier Tondichtungen nach Arnold Böcklin” Max Reger Requiem op. 144b (1915) nach Hebbel für Chor, Bariton und Orchester 2 Zum heugen Konzert Vor genau 110 Jahren, am 20.11.1906, dirigierte Max Reger im Stadheater Göngen das Städsche Orchester (verstärkt durch die Kasseler Hoapelle) mit eigenen Werken. Am 11. Mai 1916 starb er im Alter von gerade einmal 43 Jahren. Wer war dieser Komponist, der in seiner kurzen Lebenszeit weit über 1.000 Werke für nahezu alle Gaungen komponiert hat (er nannte sich scherzha „Akkordarbeiter“) und der heute hauptsächlich für seine großen Orgelwerke bekannt ist? Max Reger wurde 1873 in Weiden in der Oberpfalz geboren. Er studierte beim damali- gen „Papst der Musiktheorie“ Hugo Riemann in Sondershausen und Wiesbaden. -

Max Reger's Opus 135B and the Role of Karl Straube a Study of The

STM 1994–95 Max Reger’s Opus 135b and the Role of Karl Straube 105 Max Reger’s Opus 135b and the Role of Karl Straube A study of the intense friendship between a composer and performer that had potentially dangerous consequences upon the genesis of Reger’s work Marcel Punt Max Reger’s “Fantasie und Fuge in d-moll, op. 135b” for organ appears at a very cru- cial moment in the history of German music. Reger wrote this piece between 1914 and 1916, a period in which tonality had to give way to other principles of composi- tion, such as unity creating intervals, twelve-tone music, variable ostinato, tone co- lour-melodies, etc. With this piece, Reger stands in the middle of this “development” from Wagner to Schönberg and Webern. So although the piece is still based on tona- lity, it already shows some aspects of the music that was to supersede it, namely both the fantasy and the fugue, which are based on the interval of a small second, the first theme of the fugue which consists of 11 different tones, the second which consists of even 12 different tones, and Reger’s way of changing sound together with the phrasing and the harmonic progress of the music. Reger’s opus 135b for organ could be regar- ded as one of his most advanced and still deserves more attention than it has received to date. Most organists will still only know the piece in its definite shape, now available in the Peeters-edition. But the manuscript that was first sent to the editor Simrock in Berlin, differs quite substantially from the version that Simrock finally published. -

Cello Compositions of Max Reger

DLA doctoral thesis – a summary Péter Tamás Váray Cello compositions of Max Reger Supervisor: István Ruppert The Liszt Academy of Music 28th doctoral course classified as art, cultural, and historical sciences Budapest 2018 I. The precedents of the research I have known Max Reger mainly for his organ pieces and songs, even if he can be considered a very prolific composer with his approximately 150 works and more than 350 transcriptions, among which there are several full orchestra and chamber pieces as well. The selection of my dissertation topic was inspired by Dr Salamon Kamp, and my dedication to start the research was fueled by the support of Dr László Somfai and Dr Ferenc János Szabó. In my dissertation I have focused on a clearly delineated aspect of Reger’s work, his pieces written for the cello, which is a so far very much neglected – in Hungary practically unknown – field of research. As a first step, I scrutinized Reger’s life and oeuvre, given that in my studies I had not had the chance to familiarize myself with the career and significance of this controversial, but in Germany highly renowned, composer. Once I got my first taste of his works, it became clear that, due to their complicatedness and complexity, the analysis of the compositions will be a big challenge for a performing artist. Due to the length requirements of the dissertation, I needed to concentrate on a small yet truly exciting slice of the subject: on the solo suites and the cello- piano sonatas, and their place within the chamber music segment of Reger’s oeuvre. -

The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 Introduction Ladislav Vycpálek’S Suite for Solo Viola, Op

UNIVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Viola Stands Alone: The Rise in Sonatas and Suites for Unaccompanied Viola, 1915-1929 A document submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Music by Jacob William Adams Committee in charge: Professor Helen Callus, Chair Professor Derek Katz Professor Paul Berkowitz December 2014 The document of Jacob William Adams is approved. Paul Berkowitz Derek Katz Helen Callus, Committee Chair ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research and writing would not have been possible without tremendous support and encouragement from several important people. Firstly, I must acknowledge the UCSB faculty members that comprise my committee: Helen Callus, Derek Katz, and Paul Berkowitz. All three have provided invaluable guidance, constructive feedback, and varied points of view to consider throughout the researching and writing process, and each of them has contributed significantly to my development as a musician-scholar. Beyond my committee members, I want to thank Carly Yartz, David Holmes, Tricia Taylor, and Patrick Chose. These various staff members of the UCSB Music Department have provided much needed assistance throughout my tenure as a graduate student in the department. Finally, I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my parents, David and Martha. They instilled a passion for music and an intellectual curiosity early and often in my life. They helped me see the connections in things all around me, encouraged me to work hard and probe deeper, and to examine how seemingly disparate things can relate to one another or share commonalities. It is thanks to them and their never-ending love and support that I have been able to accomplish what I have. -

Max Reger (Geb

Max Reger (geb. Brand in der Oberpfalz, 19. März 1873 — gest. Leipzig, 11. Mai 1916) »Der Einsiedler« op. 114a (p. 1-33) für Bariton, fünfstimmigen gemischten Chor und Orchester (1914-15) auf eine Dichtung von Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857) Requiem »Seele, vergiß sie nicht« op. 144b (p. 3-37) für Altsolo, gemischten Chor und Orchester (1914-15) auf eine Dichtung von Friedrich Hebbel (1813-63) Vorwort Nach dem seinerzeit vom Verlag Lauterbach & Kuhn abgelehnten Gesang der Verklärten op. 71 (1903, Text von Busse) und direkt im Anschluß an den gigantischen 100. Psalm op. 106 (vollendet am 22. Juni 1909) waren Die Nonnen op. 112 (vollendet am 7. August 1909, Text von Martin Boelitz) das dritte großangelegte chorsymphonische Werk Max Regers, denen dann noch Die Weihe der Nacht op. 119 (1911, Text von Friedrich Hebbel), ein unvollendet gebliebenes lateinisches Requiem (1914) sowie die beiden hier erstmals in einer gemeinsamen Studienpartitur vorgelegten Werke op. 144, Der Einsiedler op. 144a und das Requiem op. 144b ‘Seele, vergiß sie nicht’, folgten. Laut Auskunft seiner Frau Elsa hatte Max Reger schon 1909 vor dem drohenden "Weltenbrand" gewarnt. Als der Erste Weltkrieg ausbrach, erwies er sich als vehementer Patriot, ersuchte sofort um Einberufung und wurde am 18. August 1914 zu seiner Verbitterung als "total untauglich nach Hause geschickt". Also leistete er seinen Tribut in Form der "dem deutschen Heere" gewidmeten Vaterländischen Ouvertüre op. 140. Am 14. Oktober 1914 schrieb Max Reger an seinen Schüler Hermann Grabner (1886-1969): "Hoffentlich bilden Sie recht viele brave Soldaten für diesen, für unsere Gegner so schmachvollen Krieg aus. Es ist unerhört, mit welcher Niederträchtigkeit und Gemeinheit dieser Krieg von England herbeigeführt und seit langer Zeit vorbereitet worden ist! — Ich arbeite an einem 'Requiem' für Soli, Chor, Orchester und Orgel 'Dem Andenken der in diesem Kriege gefallenen Helden gewidmet!'" Die Witwe berichtet (in Elsa Reger. -

Chorale Fantasia on ‘Freu Dich Sehr, O Meine Seele’ Con Espressione with the Varied Melody in the Right Hand

570960bk Reger10 US:557541bk Kelemen 3+3 24/7/10 8:42 PM Page 1 Martin Welzel The Johannes Klais Organ, Trier Cathedral, Germany (1974) Born in 1972 in Vechta, Germany, Martin Welzel received his musical training in Bremen from Michael Landsky, Hauptwerk 2. Manual C – c’’’’ Larigot 1 1/3’ Unda maris 8’ Wilfried Langosz and Käte van Tricht. He later studied Praestant 16’ Sesquialter 2fach Octave 4’ with Daniel Roth, Wolfgang Rübsam, Kristin Merscher Principal 8’ Scharf 4fach Flute octaviante 4’ and Gerald Hambitzer at the University of Music in Hohlflöte 8’ Glockencymbel 2fach Salicional 4’ Saarbrücken, where he earned Bachelor and Master of Gemshorn 8’ Dulzian 16’ Flageolett 2’ Music degrees in sacred music and organ performance, Quinte 5 1/3’ Cromorne 8’ Fourniture 6fach as well as an Artist diploma in organ performance. He Octave 4’ Cor anglais 16’ REGER holds a DMA degree in organ performance from the Nachthorn 4’ Brustwerk 3. Manual (schwellbar) Trompete 8’ University of Washington in Seattle, where he studied with Terz 3 1/5’ C – c’’’’ Clairon 4’ Carole Terry. Martin Welzel's career has included Quinte 2 2/3’ Rohrflöte 8’ Prelude and Fugue in numerous recitals in Europe and the United States, notably Superoctave 2’ Praestant 4’ Pedal C –g’ at Notre-Dame Cathedral and Saint-Sulpice in Paris, Cornett 5fach Blockflöte 4’ Untersatz 32’ E minor, Op. 85, No. 4 Washington National Cathedral, Meyerson Symphony Mixtur 5fach Nasard 2 2/3’ Principal 16’ Center and Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Cymbel 3fach Doublette 2’ Subbass 16’ Stanford University, St. -

Nur Eine Kleine Zeit

Magazin der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien Mai/Juni 2014 Nur eine kleine Zeit Max Regers „Requiem“ 1915 schrieb Max Reger sein „Requiem“ auf einen Text von Friedrich Hebbel. Die Widmung galt noch den „gefallenen deutschen Helden“ des Ersten Weltkriegs, aber die Musik straft alle Phrasen lügen und wird zum eindringlichen Klagegesang über Tod und sinnloses Opfer. „Seele, vergiss sie nicht“. „Der Mensch lebt und bestehet/ Nur eine kleine Zeit,/ Und alle Welt vergehet/ Mit ihrer Herrlichkeit./ Es ist nur einer ewig und an allen Enden/ Und wir in seinen Händen.“ Max Reger hat diese Claudius-Verse unvergleichlich zu Beginn seiner späten „Geistlichen Gesänge“ für gemischten Chor a cappella op. 138 aus dem September 1914 Musik werden lassen – als wolle er damit sein „Spätwerk“, immerhin das eines Vierzigjährigen, eröffnen: aus den kaum sechzig Takten dieses Gesangs kann man die enorme Bedeutung Regers erfassen, die immer noch, weil sein Charakterbild in der Geschichte schwankt, vielfach bezweifelt wird. Seine tiefsten Tiefen spiegeln sich hier: ein Vergänglichkeitsbewusstsein, eine Todesnähe bei aller Lebensfülle, die ihn geradezu prädestiniert hatte, das epochale „moderne“ Requiem nach und über Brahms hinaus zu schreiben. Und doch: Kaum einer spricht mehr von Regers „Requiem“ – dabei gibt es einen ganzen Komplex „Requiem“ in Regers Werk und Leben, den man sich entschlüsseln muss, will man seinen Offenbarungswert erkennen. Die geöffnete Tür Reger war gekommen zu seiner im Ersten Weltkrieg endenden „kleinen Zeit“, das Erbe der Alten, deren hohe Kunst, mit den Gefühlsinhalten seiner Gesellschaft und seiner Vision von einer Musik der Zukunft zu verbinden: neue Sprache in Musik zu schaffen, auf der Grammatik der vergangenen basierend, jedoch mit der Idiomatik eines Subjekts, das sich in dieser Periode aus dem romantischen Weltgefühl zu entfesseln sucht, um sich aufzuklären.