The Solo Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Question of the Baroque Instrumental Concerto Typology

Musica Iagellonica 2012 ISSN 1233-9679 Piotr WILK (Kraków) On the question of the Baroque instrumental concerto typology A concerto was one of the most important genres of instrumental music in the Baroque period. The composers who contributed to the development of this musical genre have significantly influenced the shape of the orchestral tex- ture and created a model of the relationship between a soloist and an orchestra, which is still in use today. In terms of its form and style, the Baroque concerto is much more varied than a concerto in any other period in the music history. This diversity and ingenious approaches are causing many challenges that the researches of the genre are bound to face. In this article, I will attempt to re- view existing classifications of the Baroque concerto, and introduce my own typology, which I believe, will facilitate more accurate and clearer description of the content of historical sources. When thinking of the Baroque concerto today, usually three types of genre come to mind: solo concerto, concerto grosso and orchestral concerto. Such classification was first introduced by Manfred Bukofzer in his definitive monograph Music in the Baroque Era. 1 While agreeing with Arnold Schering’s pioneering typology where the author identifies solo concerto, concerto grosso and sinfonia-concerto in the Baroque, Bukofzer notes that the last term is mis- 1 M. Bukofzer, Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, New York 1947: 318– –319. 83 Piotr Wilk leading, and that for works where a soloist is not called for, the term ‘orchestral concerto’ should rather be used. -

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

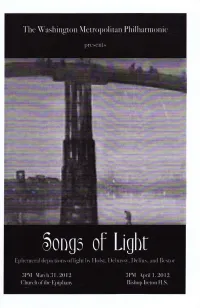

2012-0331 Program.Pdf

I\TI\OI)~I ClIO:-;~ Welcorne to Songs ofLight! JUSllikc the anists oftheir day, musicians ofthe Impressionistic CI"'J were intrigued with the cfTt.'C(S ofligtll and 50"0",11 to portray this in their music. With diminished light. the harsh cfTetts ofindustrialization were muted and these llt."\\ landst<q>cs Wert softened and made bc-Jutiful again. l1lis aftcmoon's program is filled wim ethereal depietions of light by Delius. Dehll"S)', and l-Io1st as well a~ with a sparkling new work by Charles Beslor. lei these airy musical work..<; lIallspon you to a time ofday where healilifulligiu softens the lrOublcs ofthe world bringingoullhe best ofany place. Enjo}! ,. As Illusie is lhe poetry OfSOlilld. so is paiming Ihe poclry ofsight. ~ - JUfIlt'JAblJOIf AfcNetillflllfJtler W:.ashillg'lotl Ml'tropolil.U1 rhilhanllonic. UI~"SSCS James. Music Dirt:('lOf & Condm:lor Ulys.<iCS S. James is a fonner lromhonist who studied in BOSlOll aud at Tauglcwood ..•..ith William Gibson. principal trombonist of the Bostoll Symphony On:heslra. He grddlllHcd in 1958 ....ith honurs in llIusi<: from Brown University. Mtcr a 20 yCM ~'aIttr as a surfoc-c ....~Mfare Naval Officer. followed by a second tareer as an organization and management de...e1opmem consultam. he bn-arne the music dire~1or and priocipal condtl~1or of Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic Association in 1985. The Assodation sponsors Washington Metropolitan Philharmonic. Washington ~lctropolitan YOUlh Orchestra. Washington Metropolitan Concen Orchestrd. a weekly summer chamber musie series at The Lyceum ill Old Towll Alexandria. and all anllual cOl1lpo~ition COllllletition for the Mid-Atlantic StUll'S. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Paul Jacobs, Elliott Carter, and an Overview of Selected Stylistic Aspects of Night Fantasies

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies Alan Michael Rudell University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Rudell, A. M.(2016). Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3977 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUL JACOBS, ELLIOTT CARTER, AND AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED STYLISTIC ASPECTS OF NIGHT FANTASIES by Alan Michael Rudell Bachelor of Music University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2004 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2009 _____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Joseph Rackers, Major Professor Charles L. Fugo, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Marina Lomazov, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alan Michael Rudell, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my thanks to the members of my committee, especially Joseph Rackers, who served as director, Charles L. Fugo, for his meticulous editing, J. Daniel Jenkins, who clarified certain issues pertaining to Carter’s style, and Marina Lomazov, for her unwavering support. -

Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia Or Online at Wrti.Org

Next on Discoveries from the Fleisher Collection Listen to WRTI 90.1 FM Philadelphia or online at wrti.org. Encore presentations of the entire Discoveries series every Wednesday at 7:00 p.m. on WRTI-HD2 Saturday, November 1st, 2014, 5:00-6:00 p.m. The Taste of Bach Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Concerto for Flute, Violin, Harpsichord in A minor, BWV 1044. Andrew Manze, violin (conductor), Rachel Brown, flute, Richard Egarr, harpsichord, Academy of Ancient Music. Harmonia Mundi 907283, Tr 7–9. 22:25 Bach. Concerto for Two Harpsichords and Strings in C, BWV 1061. Hank Knox, Luc Beauséjour, harpsichords, Arion, Jaap ter Linden. Early Music 7753, Tr 14–16. 16:46 Bach. Concerto for Four Harpsichords and Strings in A minor, BWV 1065. Raymond Leppard (conductor), An- drew Davies, Philip Ledger, Blandine Verlet, harpsichords, English Chamber Orchestra. Philips 4784614, Tr 13–15. 9:32 Let’s face it, the harpsichord is an acquired taste. In popular culture, never help- ful for appreciating the fine or unusual, the harpsichord is shorthand for—at best—stuffy, rich, out-of-touch, let-them-eat-cake. That’s at best. At worst, it’s sinister. And that doesn’t even count Lurch on The Addams Family. The harpsichord is a beautiful instrument that has often been misapplied. It has a delicate, refined sound, yet can help to keep the players onstage together. Indeed, before we stood conductors on their feet in front of everyone, they were often in the middle of the orches- tra, seated at and playing the harpsichord. -

557242Bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12

557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 12 DDD Tintner Memorial Edition Vol.10 8.557242 DELIUS Violin Concerto and other orchestral music Philippe Djokic, Violin Symphony Nova Scotia • Georg Tintner 557242bk Delius EC Sono 26/2/04 8:39 PM Page 2 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • VOLUME 10 TINTNER MEMORIAL EDITION • 12 VOLUMES Frederick Delius (1862-1934) Vol.1 MOZART Symphonies Nos. 31 ‘Paris’, 35 ‘Haffner’ & 40 8.557233 Violin Concerto • Irmelin Prelude • La Calinda • The Walk to the Paradise Garden Vol. 2 SCHUBERT Symphonies Nos. 8 ‘Unfinished’ & 9 ‘The Great’ 8.557234 Intermezzo from ‘Fennimore and Gerda’ • On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner Summer Night on the River • Sleigh Ride Performances recorded 5-6th December 1991 Vol. 3 BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 / SCHUMANN Symphony No.2 8.557235 Though Delius was born (as Fritz Theodore Albert, on amanuensis Eric Fenby in 1931. With spoken introductions by Georg Tintner 29th January 1862) in Bradford, England, of German In 1897 Delius completed his third opera, Koanga, Vol. 4 HAYDN Symphonies Nos.103 ‘Drumroll’ & 104 ‘London’ 8.557236 parents, he was the true cosmopolitan. He lived most of about Creole society in Louisiana and thus the first With spoken introduction by Georg Tintner his life in France, Scandinavia and America, and his African-American opera. The dance La Calinda, which music shows traces of them all. After a rather stern appeared in an earlier version in the Florida Suite, is Vol. 5 BRAHMS Symphony No. 3 & Serenade No. 2 8.557237 upbringing Delius was compelled to join the family one of Delius’ best-known and loveliest pieces. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

The Italian Double Concerto: a Study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy

The Italian Double Concerto: A study of the Italian Double Concerto for Trumpet at the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna, Italy a document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Performance Studies Division – The University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Jason A. Orsen M.M., Kent State University, 2003 B.M., S.U.N.Y Fredonia, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. Vivian Montgomery Prof. Alan Siebert Dr. Mark Ostoich © 2013 Jason A. Orsen All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents Chapter I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto………………………………………5 II. The Basilica of San Petronio……………………………………………………11 III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio…………………………………………….18 IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio……………………………………...29 V. Italian Double Concerto…………………………………………………………34 VI. Performance practice issues……………………………………………………..37 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..48 3 Outline I. Introduction: The Italian Double Concerto A. Background of Bologna, Italy B. Italian Baroque II. The Basilica of San Petronio A. Background information on the church B. Explanation of physical dimensions, interior and effect it had on a composer’s style III. Maestri di Cappella at San Petronio A. Maurizio Cazzati B. Giovanni Paolo Colonna C. Giacomo Antonio Perti IV. Composers and musicians at San Petronio A. Giuseppe Torelli B. Petronio Franceschini C. Francesco Onofrio Manfredini V. Italian Double Concerto A. Description of style and use B. Harmonic and compositional tendencies C. Compare and contrast with other double concerti D. Progression and development VI. Performance practice issues A. Ornamentation B. Orchestration 4 I. -

Unc Symphony Orchestra Library

UNC ORCHESTRA LIBRARY HOLDINGS Anderson Fiddle-Faddle Anderson The Penny-Whistle Song Anderson Plink, Plank, Plunk! Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby Arensky Silhouettes, Op. 23 Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky, Op. 35a Bach, J.C. Domine ad adjuvandum Bach, J.C. Laudate pueri Bach Cantata No. 106, “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” Bach Cantata No. 140, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” Bach Cantata No. 209, “Non sa che sia dolore” Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058 Bach Concerto No. 1 in C minor for Two Claviers, BWV 1060 Bach Concerto No. 2 in C major for Three Claviers, BWV 1064 Bach Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, BWV 1041 Bach Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 Bach Komm, süsser Tod Bach Magnificat in D major, BWV 243 Bach A Mighty Fortress Is Our God Bach O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 Bach Prelude, Choral and Fugue Bach Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Bach Suite in B minor Bach Adagio from Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Barber Adagio for Strings, Op. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No.