By Chau-Yee Lo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Double Keyboard Concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

The double keyboard concertos of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Waterman, Muriel Moore, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 18:28:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318085 THE DOUBLE KEYBOARD CONCERTOS OF CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH by Muriel Moore Waterman A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: JAMES R. -

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

Paul Jacobs, Elliott Carter, and an Overview of Selected Stylistic Aspects of Night Fantasies

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies Alan Michael Rudell University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Rudell, A. M.(2016). Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3977 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUL JACOBS, ELLIOTT CARTER, AND AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED STYLISTIC ASPECTS OF NIGHT FANTASIES by Alan Michael Rudell Bachelor of Music University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2004 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2009 _____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Joseph Rackers, Major Professor Charles L. Fugo, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Marina Lomazov, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alan Michael Rudell, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my thanks to the members of my committee, especially Joseph Rackers, who served as director, Charles L. Fugo, for his meticulous editing, J. Daniel Jenkins, who clarified certain issues pertaining to Carter’s style, and Marina Lomazov, for her unwavering support. -

Programnotes Brahms Double

Please note that osmo Vänskä replaces Bernard Haitink, who has been forced to cancel his appearance at these concerts. Program One HundRed TwenTy-SeCOnd SeASOn Chicago symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 18, 2012, at 8:00 Friday, October 19, 2012, at 8:00 Saturday, October 20, 2012, at 8:00 osmo Vänskä Conductor renaud Capuçon Violin gautier Capuçon Cello music by Johannes Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in A Minor, Op. 102 (Double) Allegro Andante Vivace non troppo RenAud CApuçOn GAuTieR CApuçOn IntermIssIon Symphony no. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 un poco sostenuto—Allegro Andante sostenuto un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio—Allegro non troppo, ma con brio This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Comments by PhilliP huscher Johannes Brahms Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg, Germany. Died April 3, 1897, Vienna, Austria. Concerto for Violin and Cello in a minor, op. 102 (Double) or Brahms, the year 1887 his final orchestral composition, Flaunched a period of tying up this concerto for violin and cello— loose ends, finishing business, and or the Double Concerto, as it would clearing his desk. He began by ask- soon be known. Brahms privately ing Clara Schumann, with whom decided to quit composing for he had long shared his most inti- good, and in 1890 he wrote to his mate thoughts, to return all the let- publisher Fritz Simrock that he had ters he had written to her over the thrown “a lot of torn-up manuscript years. -

The Proms Listening Service Radio 3’S Tom Service Proposes Onward Sonic Explorations Inspired by the Music of Tonight’S Prom

The Proms Listening Service Radio 3’s Tom Service proposes onward sonic explorations inspired by the music of tonight’s Prom BACH a kaleidoscope of new forms, groups and layers. In his Indian Brandenburg Concertos summer – composing throughout his eighties and nineties until his death at the age of 103 – Carter continued to revisit and reshape Bach’s Brandenburgs are a set of wildly innovative and dizzyingly the concerto principle, from Dialogues I and II for piano and diverse answers to the question of how musical individuals relate orchestra and his Clarinet Concerto to works that take the to larger groups. Bach doesn’t come up with anything so Brandenburg principle of a group of instruments as an ensemble of straightforward as the concerto form as it became ossified in potential soloists into the present day. That’s the effervescent energy the 19th century, in which a single soloist is set against the that drives Carter’s Boston Concerto, written for the Boston massed ranks of the orchestra. Instead, each Brandenburg Symphony Orchestra in 2002, and the Asko Concerto, composed in Concerto proposes a much more fluid solution to the question 1999–2000 for the eponymous Dutch new music group. It’s not of how a solo part or multiple solo parts weave in and out of only the example of Bach that tonight’s composers are up against: the texture of the instrumental ensemble as a whole. It’s all there are the achievements of Musgrave and Carter to contend with done with such seamless invention that it’s like looking at an too! ever-active shoal of fish in the ocean, where your attention is sometimes drawn to the dazzle and glint of individuals but then flows out to the group as a whole, in and out again, in a dance of different relationships between the players and a dance of listening on which Bach leads us in each of these concertos. -

Program Notes by Jonathan Leshnoff and Dr

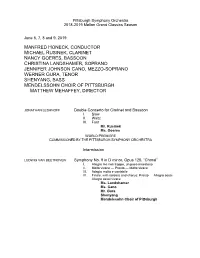

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2018-2019 Mellon Grand Classics Season June 6, 7, 8 and 9, 2019 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR MICHAEL RUSINEK, CLARINET NANCY GOERES, BASSOON CHRISTINA LANDSHAMER, SOPRANO JENNIFER JOHNSON CANO, MEZZO-SOPRANO WERNER GURA, TENOR SHENYANG, BASS MENDELSSOHN CHOIR OF PITTSBURGH MATTHEW MEHAFFEY, DIRECTOR JONATHAN LESHNOFF Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon I. Slow II. Waltz III. Fast Mr. Rusinek Ms. Goeres WORLD PREMIERE COMMISSIONED BY THE PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Intermission LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125, “Choral” I. Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso II. Molto vivace — Presto — Molto vivace III. Adagio molto e cantabile IV. Finale, with soloists and chorus: Presto — Allegro assai — Allegro assai vivace Ms. Landshamer Ms. Cano Mr. Gura Shenyang Mendelssohn Choir of Pittsburgh June 6-9, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY JONATHAN LESHNOFF AND DR. RICHARD E. RODDA JONATHAN LESHNOFF Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon (2018) Jonathan Leshnoff was born in New Brunswick, New Jersey on September 8, 1973, and resides in Baltimore, Maryland. His works have been performed by more than 65 orchestras worldwide in hundreds of orchestral concerts. He has received commissions from Carnegie Hall, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the symphony orchestras of Atlanta, Baltimore, Dallas, Kansas City, Nashville, and Pittsburgh. His Double Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon was commissioned by the Pittsburgh Symphony and co-commissioned by the Greenwich Village Orchestra and International Wolfegg Concerts of Wolfegg, Germany. These performances mark the world premiere. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, and strings. -

The Evolution of Elliott Carter's Rhythmic Practice Author(S): Jonathan W. Bernard Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 26, No

The Evolution of Elliott Carter's Rhythmic Practice Author(s): Jonathan W. Bernard Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Summer, 1988), pp. 164-203 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833189 Accessed: 07/02/2010 18:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pnm. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music. http://www.jstor.org THE EVOLUTIONOF ELLFTOTTCARTER'S RHYTHMICPRACTICE JONATHANW. BERNARD INTRODUCTION ELLIOTT CARTER'SWORK over the past forty years has made him per- haps the most eminent living American composer, and certainly one of the most important composers of art music in the Western world. -

Vincent Persichetti's Ten Sonatas for Harpsichord

STYLE AND COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUES IN VINCENT PERSICHETTI’S TEN SONATAS FOR HARPSICHORD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY MIRABELLA ANCA MINUT DISSERTATION ADVISORS: KIRBY KORIATH AND MICHAEL ORAVITZ BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 ii Copyright © 2009 by Mirabella Anca Minut All rights reserved Music examples used in this dissertation comply with Section 107, Fair Use, of the Copyright Law, Title 17 of the United States Code. Sonata for Harpsichord, Op. 52 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1973, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Second Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 146 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Third Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 149 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Fourth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 151 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Fifth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 152 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1984, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Sixth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 154 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1977, 1984 Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Seventh Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 156 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1985, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Eighth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 158 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1987, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Ninth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 163 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1987, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Tenth Harpsichord Sonata, [Op. 167] by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1994, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. First String Quartet, Op. 7 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1977, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my doctoral committee members, Dr. Kirby Koriath, Dr. Michael Oravitz, Dr. Robert Palmer, Dr. Raymond Kilburn, and Dr. Annette Leitze, as well as former committee member Dr. -

Trumpet Music by Women Composers

Trumpet Music by Women Composers Amy Dunker, DMA Professor of Music Theory, Composition and Trumpet Clarke University 1550 Clarke Drive Dubuque, IA 52001 [email protected] www.amydunker.com If you perform a composer’s work, please email them and/or send them a program. It is important to know that your work is appreciated! Trumpet Alone Beamish, Sally: Fanfare for Solo Trumpet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.warwickmusic.com/Main-Catalogue/Sheet-Music/Trumpet/Solo-Trumpet/Beamish-Fanfare- for-Solo-Trumpet-TR065 Beat, Janet: Fireworks in Steel (Trumpet Alone) http://furore-verlag.de/shop/noten/trompete/ Bernofsky, Lauren: Fantasia (Trumpet Alone) http://laurenbernofsky.com/works.php Bielawa, Lisa: Synopsis No. 5 (Trumpet Alone) http://lisabielawa.typepad.com/works_section/ Bingham, Judith: Enter Ghost Act 1, Scene 3 of Hamlet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/enter-ghost-act-1-scene-3-of-hamlet-2002-sheet-music/19110817 Bouchard, Linda: Propos (Trumpet Alone or Trumpet Ensemble) http://www.musiccentre.ca/node/21128 Campbell, Karen: Pieces (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=85460 Clarke, Rosemary: Winter’s Winds (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86228 Cronin, Tanya: Undercurrents (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86700 Dinescu, Violeta: Abendandacht (Trumpet Alone) http://www.composers21.com/compdocs/dinescuv.htm Dunker, Amy: Advanced Solos (Trumpet Alone) 1. "Distant -

Orchestral-Dialogues: Accepting Self, Accepting Others –

Orchestral-Dialogues: Accepting Self, Accepting Others – Translating Deep Listening Skills to Transformative Dialogue Skills A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Janelle S. Junkin in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Orchestral Dialogues Ethnography ii ©Copyright 2017 Janelle S. Junkin. All Rights Reserved. Orchestral Dialogues Ethnography iii Acknowledgements To my friends, family and faith community, I could not have completed this PhD journey without you. Your words of encouragement, of support, and your presence have been invaluable. To Andrea and Chantelle, our monthly spiritual direction meetings kept me grounded and reminded me who I am; I love you both and treasure our friendship and sisterhood. Karen, you are brilliant and your ability to give (and receive) is incomparable. I know that I would not have completed this process without your spiritual guidance, your encouragement and your loving support, thank you for all that you have done for me. A huge thank you to the staff, parents and guardians and children of Orchestral Dialogues. You are the reason that this dissertation is what it is. I have learned so much from each of you and I have appreciated all of you checking in about the research, asking me how I am doing and in general being a support to me through this whole process. It was a humbling experience to learn with and from you, thank you for trusting me and allowing me to be a part of this new community experience. Nathan Corbitt and Vivian Nix-Early and the staff at BuildaBridge International without you Orchestral Dialogues might have remained only a dream. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

Solo Oboe, English Horn with Band

A Nieweg Chart Solo Oboe or Solo English Horn with Band or Wind Ensemble 95 editions April 2017 The 2017 Chart is an update of the 2010 Chart. It is not a complete list of all available works for Oboe or EH and band. Works with prices listed are for sale from any music dealer. Prices current as of 2010. Look at the publisher’s website for the current prices. Works marked rental must be hired directly from the publisher listed. Sample Band Instrumentation code: 3fl[1.2.3/pic] 2ob 7cl[Eb.1.2.3.acl.bcl.cbcl] 3bn[1.2.cbn] 4sax[a.a.t.b] — 4hn 3tp 3tbn euph tuba double bass — tmp+3perc — hp, pf, cel This listing gives the number of parts used in the composition, not the number of players. ------------------ Abbado, Marcello (b. Milan, 1926; ) Concerto in C minor (complete) Arranger / Editor: Trans. Charles T. Yeago Instrumentation: Oboe solo and band Pub: BAS Publishing. SOS-217 http://www.baspublishing.com ------------------ ALBINONI, Tommaso (1674-1745) Concerto in F for TWO Oboes and Band Adapted: Paul R. Brink Grade Level: Medium Pub: Bas Publishing Co.; Score and band set SOS-226 -$65.00 | 2 oboes and piano ENS-708. $10.00 ------------------ ARENZ, Heinz (b. 1924) German wind director, administrator, and composer Concertino fur Solo Oboe und Blasorchester Dur: 7'39" Grade Level: solo 6, band 5 Pub: HeBu Music Publishing; Band score and set 113.00 € Oboe and Piano 11.00 € ------------------ ATEHORTUA, Blas Emilio (b. Medellin, Columbia, 3 October 1933) Concerto for Oboe and Wind Symphony Orchestra Instrumentation listed <http://www.edition-peters.com/pdf/Albinoni-Grieg.pdf> Dur: 15' Pub: C.