Orchestral-Dialogues: Accepting Self, Accepting Others –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elliott Carter Works List

W O R K S Triple Duo (1982–83) Elliott Carter Collection, Paul Sacher Foundation Basel ORCHESTRA Adagio tenebroso (1994) ............................................................ 20’ (H) 3(II, III=picc).2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(4):BD/ 4bongos/glsp/4tpl.bl/cowbells/vib/2susp.cym/2tom-t/2wdbl/SD/xyl/ tam-t/marimba/wood drum/2metal block-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Allegro scorrevole (1996) ........................................................... 11’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2(II=Ebcl).bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-perc(4):timp/glsp/xyl/vib/ 4bongos/SD/2tom-t/wdbl/3susp.cym/2cowbells/guiro/2metal blocks/ 4tpl.bl/BD/marimba-harp-pft-strings (also see Symphonia: sum fluxae pretium spei) Anniversary (1989) ....................................................................... 6’ (H) 3(III=picc).2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(2):vib/marimba/xyl/ 3susp.cym-pft(=cel)-strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Boston Concerto (2002) .............................................................. 19’ (H) 3(II,III=picc).2.corA.3(III=bcl).3(III=dbn)-4.3.3.1-perc(3):I=xyl/vib/log dr/4bongos/high SD/susp.cym/wood chime; II=marimba/log dr/ 4tpl.bl/2cowbells/susp.cym; III=BD/tom-t/4wdbls/guiro/susp.cym/ maracas/med SD-harp-pft-strings A Celebration of Some 100 x 150 Notes (1986) ....................... 3’ (H) 2.picc.2.corA.2.bcl.2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp.perc(1):glsp/vib-pft(=cel)- strings(16.14.12.10.8) (also see Three Occasions for Orchestra) Concerto for Orchestra (1969) .................................................. -

By Chau-Yee Lo

Dramatizing the Harpsichord: The Harpsichord Music of Elliott Carter by Chau-Yee Lo “I regard my scores as scenarios, auditory scenarios, for performers to act out their instruments, dramatizing the players as individuals and partici- pants in the ensemble.”1 Elliott Carter has often stated that this is his creative standpoint, his works from solo to orchestral pieces growing from the dramatic possibilities inherent in the sounds of the instruments. In this article I will investigate how and to what extent this applies to Carter’s harp- sichord music. Carter has written two works for the harpsichord: Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord was completed in 1952, and Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras in 1961. Both commissions were initiated by harpsichordists: the first by Sylvia Marlowe (1908–81) and the Harpsichord Quartet of New York, for whom the Sonata was written, the latter by Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911–84), who had been Carter’s fellow student at Harvard. Both works encapsulate a significant development in Carter’s technique of composition, and bear evidence of his changing approach to music in the 1950s. Shortly after completing the Double Concerto Carter started writing down the interval combinations he had frequently been using. This exercise continued and became more systematic over the next two decades, and the result is now published as the Harmony Book.2 Carter came to write for the harpsichord for the first time in the Sonata. Here the harpsichord is the only soloist, the other instruments being used as a frame. In particular Carter emphasizes the wide range of tone colours available on the modern harpsichord, echoing these in the different musi- cal characters of the other instruments. -

Trumpet Music by Women Composers

Trumpet Music by Women Composers Amy Dunker, DMA Professor of Music Theory, Composition and Trumpet Clarke University 1550 Clarke Drive Dubuque, IA 52001 [email protected] www.amydunker.com If you perform a composer’s work, please email them and/or send them a program. It is important to know that your work is appreciated! Trumpet Alone Beamish, Sally: Fanfare for Solo Trumpet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.warwickmusic.com/Main-Catalogue/Sheet-Music/Trumpet/Solo-Trumpet/Beamish-Fanfare- for-Solo-Trumpet-TR065 Beat, Janet: Fireworks in Steel (Trumpet Alone) http://furore-verlag.de/shop/noten/trompete/ Bernofsky, Lauren: Fantasia (Trumpet Alone) http://laurenbernofsky.com/works.php Bielawa, Lisa: Synopsis No. 5 (Trumpet Alone) http://lisabielawa.typepad.com/works_section/ Bingham, Judith: Enter Ghost Act 1, Scene 3 of Hamlet (Trumpet Alone) http://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/enter-ghost-act-1-scene-3-of-hamlet-2002-sheet-music/19110817 Bouchard, Linda: Propos (Trumpet Alone or Trumpet Ensemble) http://www.musiccentre.ca/node/21128 Campbell, Karen: Pieces (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=85460 Clarke, Rosemary: Winter’s Winds (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86228 Cronin, Tanya: Undercurrents (Trumpet Alone) http://library.newmusicusa.org/library/composition.aspx?CompositionID=86700 Dinescu, Violeta: Abendandacht (Trumpet Alone) http://www.composers21.com/compdocs/dinescuv.htm Dunker, Amy: Advanced Solos (Trumpet Alone) 1. "Distant -

Solo Oboe, English Horn with Band

A Nieweg Chart Solo Oboe or Solo English Horn with Band or Wind Ensemble 95 editions April 2017 The 2017 Chart is an update of the 2010 Chart. It is not a complete list of all available works for Oboe or EH and band. Works with prices listed are for sale from any music dealer. Prices current as of 2010. Look at the publisher’s website for the current prices. Works marked rental must be hired directly from the publisher listed. Sample Band Instrumentation code: 3fl[1.2.3/pic] 2ob 7cl[Eb.1.2.3.acl.bcl.cbcl] 3bn[1.2.cbn] 4sax[a.a.t.b] — 4hn 3tp 3tbn euph tuba double bass — tmp+3perc — hp, pf, cel This listing gives the number of parts used in the composition, not the number of players. ------------------ Abbado, Marcello (b. Milan, 1926; ) Concerto in C minor (complete) Arranger / Editor: Trans. Charles T. Yeago Instrumentation: Oboe solo and band Pub: BAS Publishing. SOS-217 http://www.baspublishing.com ------------------ ALBINONI, Tommaso (1674-1745) Concerto in F for TWO Oboes and Band Adapted: Paul R. Brink Grade Level: Medium Pub: Bas Publishing Co.; Score and band set SOS-226 -$65.00 | 2 oboes and piano ENS-708. $10.00 ------------------ ARENZ, Heinz (b. 1924) German wind director, administrator, and composer Concertino fur Solo Oboe und Blasorchester Dur: 7'39" Grade Level: solo 6, band 5 Pub: HeBu Music Publishing; Band score and set 113.00 € Oboe and Piano 11.00 € ------------------ ATEHORTUA, Blas Emilio (b. Medellin, Columbia, 3 October 1933) Concerto for Oboe and Wind Symphony Orchestra Instrumentation listed <http://www.edition-peters.com/pdf/Albinoni-Grieg.pdf> Dur: 15' Pub: C. -

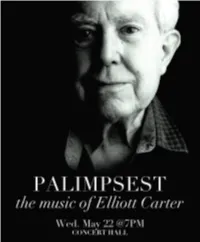

20130522-Palimpsest2.Pdf

UC San Diego • Division of Arts and Humanities • Department of Music presents Dean’s Night at the Prebys Palimpsest The Music of Elliott Carter Conducted by Donald Palma / Curated by Aleck Karis Double Trio (2011) Leah Asher, violin Judith Hamann, cello Calvin Price, trumpet Eric Starr, trombone Kyle Blair, piano Stephen Solook, percussion colla voce by Stephen Lewis (world premiere) (2013) Tiffany DuMouchelle, soprano Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Leah Asher, viola Jennifer Bewerse, cello Scott Worthington, bass Christine Tavolacci, flute Jonathan Davis, oboe Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Todd Moellenberg, piano Ryan Nestor, percussion Triple Duo (1983) Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Judith Hamann, cello Rachel Beetz, flute Curt Miller, clarinet Kyle Adam Blair, piano Jonathan Hepfer, percussion intermission Hiyoku (2001) Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Curt Miller, clarinet Elliott’s Instruments by Rand Steiger (2010) Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Judith Hamann, cello Rachel Beetz, flute Curt Miller, clarinet Kyle Adam Blair, piano Jonathan Hepfer, percussion A Mirror on Which to Dwell (1975) Alice Teyssier, soprano Batya MacAdam-Somer, violin Leah Asher, viola Jennifer Bewerse, cello Scott Worthington, bass Christine Tavolacci, flute Jonathan Davis, oboe Samuel Dunscombe, clarinet Todd Moellenberg, piano Ryan Nestor, percussion PRORGRAM NOTES Remembering Elliott Carter Composer Elliott Carter passed away November 5, 2012 just five weeks short of his 104th birthday. In recent years, from his perch above West 12th Street, flowed a most remarkable steam of works of imagination, craft, wit and humanity. It seemed the older he became the more he had to say. And the more the world wanted to listen. Many of us had the great privilege of working very closely with Elliott in numerous orchestral, chamber and solo settings. -

Howard Brubeck Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9f59r2jc No online items Finding aid of the Howard Brubeck Papers Processed by Shan Sutton and Vue Thao Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University of the Pacific Library 3601 Pacific Ave. Stockton, CA 95211 Phone: (209) 946-2404 Fax: (209) 946-2942 URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Library/Find/Holt-Atherton-Special-Collections.html © 2007 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Finding aid of the Howard MSS 43 1 Brubeck Papers Finding aid of the Howard Brubeck Papers Collection number: MSS 43 Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University of the Pacific Library Stockton, California Processed by: Processed by Shan Sutton and Vue Thao Date Completed: 2004 Encoded by: Michael Wurtz © 2007 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Howard Brubeck papers Dates: 1948-1987 Collection number: MSS 43 Creator: Brubeck, Howard, 1916-1993 Repository: University of the Pacific. Library. Holt-Atherton Dept. of Special Collections Stockton, California 95211 Abstract: The collection consists primarily of musical scores by Howard Brubeck. Several files of documents are also in the collection, including letters from Howard Brubeck to Dave and Iola Brubeck concerning various projects in 1961 and 1962. Physical location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights Permission for publication is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained by the researcher. -

A Multifaceted Approach to Analyzing Form in Elliott Carter's Boston Concerto Alan Theisen

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 A Multifaceted Approach to Analyzing Form in Elliott Carter's Boston Concerto Alan Theisen Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A MULTIFACETED APPROACH TO ANALYZING FORM IN ELLIOTT CARTER'S BOSTON CONCERTO By ALAN THEISEN A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Alan Theisen defended on June 8, 2010. ____________________________________ Michael Buchler Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Denise Von Glahn University Representative ____________________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Committee Member ____________________________________ Evan Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my dissertation advisor and good friend Michael Buchler, for his guidance on this project and throughout my stay at Florida State University. I would also like to thank my committee, Jane Piper Clendinning, Denise Von Glahn, and Evan Jones, for their encouragement and insightful comments during the writing process. My family also deserves thanks for the endless supply of support they have provided over the years; a special thanks go to my parents for insisting that I follow my passion rather than simply chasing the Almighty Dollar. I would also like to thank Joseph Brumbeloe at the University of Southern Mississippi for his support over the years and for encouraging me to continue my music theory studies, particularly those on post-tonal topics. -

Elliott Carter: Ballets

ELLIOTT CARTER: BALLETS POCAHONTAS | THE MINOTAUR POCAHONTAS (1939) THE MINOTAUR (1947) ELLIOTT CARTER 1908–2012 [1] Overture 1:59 [8] Overture 0:56 [2] John Smith and Rolfe lost in the Virginia SCENE I: King Minos’ Palace in Crete POCAHONTAS Forest 3:21 [9] Queen Pasiphae dresses for her tryst with [3] The Indians ambush John Smith 2:12 the sacred bull 4:56 THE MINOTAUR [4] Princess Pocahontas and her Ladies 3:53 [10] Pasiphae’s dance with the bulls 3:02 [5] John Smith is tortured by Indians and [11] Interlude 1:22 saved by Pocahontas 6:25 SCENE II: Before Labyrinth BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [ ] 6 John Smith presents young Rolfe to [12] Building of the Labyrinth 2:41 Gil Rose, conductor Pocahontas, Rolfe and Pocahontas [ ] dance 8:06 13 Procession and entrance of King Minos 2:07 [7] Pavane, Farewell of Indians, Pocahontas [ ] and Rolfe sail for England 5:02 14 Sacrifice of the Greek victims 1:29 [15] Ariadne dances with Theseus (Pas de Deux) 4:59 [16] The Labyrinth 2:03 [17] Theseus’ farewell as he enters the Labyrinth 1:33 [18] Ariadne’s thread unwinds 1:15 [19] The Fight with the Minotaur 1:17 [20] Ariadne rewinds her thread to lead Theseus out of the Labyrinth 2:56 [21] Greeks and Theseus emerge from Labyrinth 1:16 [22] Theseus and the Greeks prepare to leave Crete 3:06 TOTAL 65:57 COMMENT By Elliott Carter . PHOTO BY GEORGE PLATT LYNES. PLATT GEORGE BY . PHOTO FROM “THE COMPOSER’S CHOICES” (C. 1960) My first large orchestral work, written in 1938—a ballet on the subject of Pocahontas—is POCAHONTAS full of suggestions of things that were to remain important to me, as well as of others which were later rejected or completely transformed because they no longer seemed cogent. -

Molly Morkoski

NORTH CAROLINA NEWMUSIC INITIATIVE INITIATING NEW IDEAS ABOUT NEW MUSIC WWW.ECU.EDU/NEWMUSIC and the CELEBRATING OUR 20th SEASON OF NEW SOUNDS 2 0 1 9 - 2 0 2 0 NORTH CAROLINA All events free, 7:30pm in A.J. Fletcher Recital Hall, unless noted NEWMUSIC INITIATIVE à Molly Morkoski, piano ß 20th SEASON September 12, 2019 Jason Calloway, cello presents October 15, 2019 Premiere Performances Student composers/student performers November 21, 2019 The Wavefield Ensemble MOLLY MORKOSKI January 23, 2020 ECU Symphony Orchestra piano Jorge Richter, Director Matthew Ricketts’ Lilt, and much more February 8, 2020 Frequencies Student contemporary music ensemble February 13, 2020 ECU Symphony Orchestra Supported by funding from the Jorge Richter, Director 15th Annual Composition Competition Winner, Robert L. Jones Distinguished Professorship and Travis Alford’s …is the beginning is the end is… and listeners like you. March 7, 2020, Wright Auditorium The Music of Lei Liang WORLD PREMIERE NEWMUSIC INITIATIVE COMMISSION ECU NewMusic Camerata, William Staub, conductor March 20, 2020 Premiere Performances Student composers/student performers March 26, 2020 Premiere Performances Student composers/student performers Thursday, September 12, 2019, 7: 30pm April 7, 2020 A.J. Fletcher Recital Hall, Greenville, NC This evening’s program MOLLY MORKOSKI, piano NORTH CAROLINA NEWMUSIC INITIATIVE INITIATING NEW IDEAS ABOUT NEW MUSIC A Bag of Tails (codas for solo piano) (2016) John Harbison (b. 1938) The NORTH CAROLINA NEWMUSIC INITIATIVE is made possible only I. Robert Levin with the generous sponsorship of foundations, corporations and II. Gilbert Kalish individuals. We are profoundly grateful for the support they offer, and III. -

Dialogues Composer Anatolijus Šenderovas

DIALOGUES COMPOSER ANATOLIJUS ŠENDEROVAS e music of Anatolijus Šenderovas (21 August 1945–25 March 2019), one of the most famous and original Lithuanian composers, is played in many countries. It combines different means of modern musical language with the archaic traditions of Lithuanian culture and old Jewish music. In 1997, Šenderovas was awarded the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Arts. is four-chapter monograph is the first work dedicated to the creative life of Šenderovas. e first chapter is devoted to the Šenderovas family of musicians, who left an indelible imprint on the musical life of the second half of twentieth- century Lithuania, including the beginning of Šenderovas’ creative path and the key personalities who had an important influence on his worldview. e second chapter discusses the general principles of his creative work, describes what was characteristic of the two periods in the artist’s creative life and his most prominent works. e third chapter is devoted to the importance of the Jewish theme, and the fourth chapter contains conversations with the composer himself and words or texts written by his friends and fellow performers. Chapter I. IN THE BEGINNING. PERSONALITIES e Šenderovas family were Litvaks who came from the Mogilev province in Belarus. Jakov Šenderov (1893–1974) was a klezmer, a double-bass player, he also played the violin and trumpet quite well. His son, Michail Šenderov (1917– 1984), became one of the most famous Lithuanian cellists. He studied at the N. Rimsky-Korsakov State Conservatory in St. Petersburg with Professor Alexan- der Strimer and at the Belarusian State Conservatory with Associate Professor Alexander Vlasov. -

Elliott Carter's March

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Fall 12-14-2015 Elliott aC rter’s March: An Applicable Analysis Troy W. Palmer Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Palmer, Troy W., "Elliott aC rter’s March: An Applicable Analysis" (2015). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 590. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/590 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ELLIOTT CARTER’S MARCH: AN APPLICABLE ANALYSIS A Capstone Experience Thesis Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By: Troy W. Palmer ***** Western Kentucky University 2015 CE/T Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark Berry, Advisor Dr. Mary Wolinski ______________________ Advisor Dr. Victoria Lapoe Department of Music Copyright by Troy W. Palmer 2015 ABSTRACT This thesis, in summation, can be divided into two parts. The first half focuses on the story of Eight Pieces for Four Timpani, composed by Elliott Carter and published in 1968. Both its compositional and performance history are addressed. The compositional history starts with the writing of the first version of Carter’s music, Six Pieces for Kettledrums, written in 1950; next, the revision process is addressed, including the actual revisions seen in March. -

Celestial Dialogues for Voice Clarinet Strings and Percussion Sheet Music

Celestial Dialogues For Voice Clarinet Strings And Percussion Sheet Music Download celestial dialogues for voice clarinet strings and percussion sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of celestial dialogues for voice clarinet strings and percussion sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3180 times and last read at 2021-10-01 09:25:11. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of celestial dialogues for voice clarinet strings and percussion you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Voice Ensemble: String Orchestra Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Dialogues For Soprano And Percussion Performance Score Dialogues For Soprano And Percussion Performance Score sheet music has been read 2806 times. Dialogues for soprano and percussion performance score arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 14:32:16. [ Read More ] Al Hanisim For Voice Clarinet Strings And Percussion Al Hanisim For Voice Clarinet Strings And Percussion sheet music has been read 2619 times. Al hanisim for voice clarinet strings and percussion arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-30 07:00:43. [ Read More ] Celestial Light For Choir Satb And Strings Or Keyboard Celestial Light For Choir Satb And Strings Or Keyboard sheet music has been read 3565 times. Celestial light for choir satb and strings or keyboard arrangement is for Early Intermediate level.