Five Murders in a Fictional City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

Author Characters in Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett

Jesper Gulddal Putting People in Jail, Putting People in Books: Author Characters in Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett Abstract: The use of authors as fictional characters is a shared feature of two novels by authors who are often seen as diametrical opposites: Agatha Christie’s Death in the Clouds (1935) and Dashiell Hammett’s The Dain Curse (1928–1929). This article argues that the fictional authors have significant implications for our understanding of the two novels, not only because they serve as mediums for reflection on the detection genre and its conventions, but also, more impor- tantly, because they initiate a complex interplay between conflicting forms of authority – a game of truth and fiction that threatens the authority of the detec- tive protagonist and thereby calls into question the authoritative self-interpre- tation of the mystery plot as presented in the form of the detective’s solution. The article presents a comparative analysis of two writers who are rarely studied together and may seem to have little in common, embodying as they do two dis- tinctive styles of detective fiction. As the analysis shows, the close proximity of detectives and authors in both novels makes for an important and overlooked connection between them, bringing to light a set of shared epistemological ironies. Keywords: Agatha Christie, authors as characters, Dashiell Hammett, detective fiction, metafiction The career of crime fiction as an area of academic criticism has always been char- acterized by an ambiguous relationship to its object. On the one hand, scholars in popular fiction and cultural studies have done much to raise the status of crime fiction as a genre that is produced, bought, read, translated, and adapted on a colossal scale and is arguably the only literary genre with a truly global reach. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2017 a Conversation with Richard Layman 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2017 Morphing Bodies: Strategies of Embodiment in Contemporary US Cultural Practices A Conversation with Richard Layman Benoît Tadié Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/8961 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.8961 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Benoît Tadié, “A Conversation with Richard Layman”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2017, Online since 29 November 2018, connection on 20 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/ 8961 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.8961 This text was automatically generated on 20 May 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. A Conversation with Richard Layman 1 A Conversation with Richard Layman Benoît Tadié Transatlantica, 1 | 2017 A Conversation with Richard Layman 2 Photograph of Richard Layman The Big Book of the Continental Op, book cover Introduction 1 Richard Layman is the world’s foremost scholar on Dashiell Hammett. Among the twenty books he has written or edited are nine on Hammett, including the definitive bibliography (Dashiell Hammett, A Descriptive Bibliography, 1979), Shadow Man, the first full-length biography (1981), Hammett’s Selected Letters (with Julie M. Rivett, Hammett’s granddaughter, as Associate Editor, 2001), Discovering The Maltese Falcon and Sam Spade (2005, and The Hunter and Other Stories (2013), with Rivett. His books have twice been nominated for the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award. 2 With Rivett, he has recently edited The Big Book of the Continental Op (Vintage Crime/ Black Lizard, 2017), which for the first time gathers the complete canon of Hammett’s first detective, the nameless Continental Op (for Operative). -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

Culture-Bound Collocations in Bestsellers: a Study of Their Translations from English Into Turkish Yeşim Dinçkan

Document generated on 09/30/2021 7:54 a.m. Meta Journal des traducteurs Translators' Journal Culture-Bound Collocations in Bestsellers: A Study of Their Translations from English into Turkish Yeşim Dinçkan Volume 55, Number 3, September 2010 Article abstract This paper discusses the treatment of culture-bound collocations in URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/045065ar translations of three recent English bestsellers into Turkish. The findings are DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/045065ar categorized as per the nature of the example and translation strategy, and they are further discussed within the framework of domestication and foreignizing. See table of contents Factors that may affect translators, such as context, the demands of publishers in Turkey and the genre of the novels – bestsellers – and the relations between best-sellerization, popular fiction, and translation are also discussed. The Publisher(s) conclusion includes reflections concerning the consistency in the choices of translators, the least preferred strategies and eleven factors that may affect the Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal translators of bestsellers. It is argued that the fact that the source language is English and the source books are bestsellers have affected the choices of the ISSN translators. In conclusion, some suggestions in reference to the translation of bestsellers are made and it is emphasized that not only translations of classical 0026-0452 (print) literature, but also of popular fiction constitute a fruitful field of study for 1492-1421 (digital) translation scholars. Explore this journal Cite this article Dinçkan, Y. (2010). Culture-Bound Collocations in Bestsellers: A Study of Their Translations from English into Turkish. -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 "We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form Kendall G. Pack Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Kendall G., ""We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4247. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE WANT TO GET DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY”: THE MODERN HARDBOILED DETECTIVE IN THE NOVELLA FORM by Kendall G. Pack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in English (Literature and Writing) Approved: ____________________________ ____________________________ Charles Waugh Brian McCuskey Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ ____________________________ Benjamin Gunsberg Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Kendall Pack 2015 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “We want to get down to the nitty-gritty”: The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form by Kendall G. Pack, Master of Science Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Charles Waugh Department: English This thesis approaches the issue of the detective in the 21st century through the parodic novella form. -

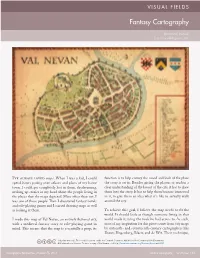

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ________________ No. 10-1743 ________________ Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros. Consumer Products, * Inc.; Turner Entertainment Co., * * Appellees, * * v. * Appeal from the United States * District Court for the X One X Productions, doing * Eastern District of Missouri. business as X One X Movie * Archives, Inc.; A.V.E.L.A., Inc., * doing business as Art & Vintage * Entertainment Licensing Agency; * Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc.; Leo * Valencia, * * Appellants. * _______________ Submitted: February 24, 2011 Filed: July 5, 2011 ________________ Before GRUENDER, BENTON, and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ________________ GRUENDER, Circuit Judge. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., X One X Productions, and Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc. (collectively, “AVELA”) appeal a permanent injunction prohibiting them from licensing certain images extracted from publicity materials for the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, as well as several animated short films featuring the cat- and-mouse duo “Tom & Jerry.” The district court issued the permanent injunction after granting summary judgment in favor of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc., Warner Bros. Consumer Products, Inc., and Turner Entertainment Co. (collectively, “Warner Bros.”) on their claim that the extracted images infringe copyrights for the films. For the reasons discussed below, we affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand for appropriate modification of the permanent injunction. I. BACKGROUND Warner Bros. asserts ownership of registered copyrights to the 1939 Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM”) films The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Before the films were completed and copyrighted, publicity materials featuring images of the actors in costume posed on the film sets were distributed to theaters and published in newspapers and magazines. -

Formulating Western Fiction in Garrett Touch of Texas

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume 2, Number 2, May 2018 Pp. 142 -155 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no2.10 Formulating Western Fiction in Garrett Touch of Texas Elisabeth Ngestirosa Endang Woro Kasih Faculty of Art and Education, Universitas Teknokrat Indonesia, Bandarlampung, Indonesia Abstract Western fiction as one of the popular novels has some common conventions such as the setting of life in frontier filled with natural ferocity and uncivilized people. This type of fiction also has a hero who is usually a ranger or cowboy. This study aims to find a Western fiction formula and look for new things that may appear in the novel Touch of Texas as a Western novel. Taking the original convention of Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, this study also looks for the invention and convention of Touch of Texas by using Cawelti’s formula theory. The study finds that Garrett's Touch of Texas not only features a natural malignancy against civilization, a ranger as a single hero, and a love story, but also shows an element of revenge and the other side of a neglected minority life. A hero or ranger in this story comes from a minority group, a mixture of white blood and Indians. The romance story also shows a different side. The woman in the novel is not the only one to be saved, but a Ranger is too, especially from the wounds and ridicule of the population as a ranger of mixed blood. The story ends with a romantic tale between Jake and Rachel. Further research can be done to find the development of western genre with other genres such as detective and mystery.