Small Episodes, Big Detectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BKCG Wins $80 Million in Hollywood Accounting Trial. . . So

SPRING 2019 EDITION “Just One More Thing . .” Ninth Circuit Delivers Justice, And A Serving BKCG Wins $80 Million in Hollywood Accounting Trial. So Far Of Cold Pizza, In Latest ADA Ruling BKCG’s trial team of Alton Burkhalter, Dan Kessler and Keith Butler have now completed two phases The Americans with Disabilities Act (the “ADA”) established a national of a three-phase trial for the creators of the television series Columbo. BKCG’s clients are William mandate for the elimination of discrimination against individuals Link and Christine Levinson Wilson, the daughter of the late Richard Levinson. Link and Levinson with disabilities. Title III of the ADA entitles all individuals to the “full created, wrote and produced a number of award-winning TV shows for Universal Studios, including and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, Murder She Wrote, Mannix, and Columbo. advantages, or accommodations of any place of public accommodation by any person who owns, leases (or leases to), or operates a place of Alton Burkhalter extended his jury trial win streak with Phase 1, where the jury returned unanimous public accommodation.” 12-0 verdicts in less than 90 minutes on all questions put to them. This was significant because it established a baseline of substantial damages and dispelled Universal’s affirmative defense based In a ruling that could only be surprising to those who have not been following recent trends in the law, the Ninth Circuit of the U.S. Court on statute of limitations. of Appeal decided that the ADA also applies to the internet and Dan Kessler led the team to victory on Phase 2, in which a number of other high stakes issues were cyberspace! In 2016, a blind man named Guillermo Robles filed a tried in a bench trial before the Honorable Judge Richard Burdge. -

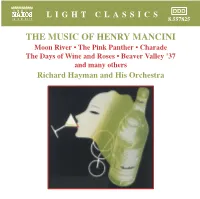

THE MUSIC of HENRY MANCINI the Boston Pops Orchestra During Arthur Fiedler’S Tenure, Providing Special Arrangements for Dozens of Their Hit Albums and Famous Singles

557825 bk ManciniUS 2/11/05 09:48 Page 4 Richard Hayman LIGHT CLASSICS DDD One of America’s favourite “Pops” conductors, Richard Hayman was Principal “Pops” conductor of the Saint 8.557825 Louis, Hartford and Grand Rapids symphony orchestras, of Orchestra London Canada and the Calgary Philharmonic Orchestra, and also held the post with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra for many years. His original compositions are standards in the repertoire of these ensembles as well as frequently performed selections by many orchestras and bands throughout the world. For over thirty years, Richard Hayman served as the chief arranger for THE MUSIC OF HENRY MANCINI the Boston Pops Orchestra during Arthur Fiedler’s tenure, providing special arrangements for dozens of their hit albums and famous singles. Under John Williams’ direction, the orchestra continues to programme his award- winning arrangements and orchestrations. Though more involved with the symphony orchestra circuit, Richard Moon River • The Pink Panther • Charade Hayman served as musical director and/or master of ceremonies for the tour shows of many popular entertainers: Kenny Rogers, Johnny Cash, Olivia Newton-John, Tom Jones, Englebert Humperdinck, The Carpenters, The The Days of Wine and Roses • Beaver Valley ’37 Osmonds, Al Hirt, Andy Williams and many others. Richard Hayman and His Orchestra recorded 23 albums and 27 hit singles for Mercury Records, for which he and many others served as musical director for twelve years. Dozens of his original compositions have been recorded by various artists all over the world. He has also arranged and conducted recordings for more than 50 stars of the motion Richard Hayman and His Orchestra picture, stage, radio and television worlds, and has also scored Broadway shows and numerous motion pictures. -

Music from Peter Gunn

“The Music from ‘Peter Gunn’”--Henry Mancini (1958) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Mark A. Robinson (guest post)* Henry Mancini Henry Mancini (1924-1994) was the celebrated composer of a parade of song standards, particularly remembered for his work in television and film composition. Among his sparkling array of memorable melodies are the music for “The Pink Panther” films, the “Love Theme from ‘Romeo and Juliet’,” and his two Academy Award-winning collaborations with lyricist Johnny Mercer, “Moon River” for the 1961 film “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” and the title song for the 1962 feature “Days of Wine and Roses.” Born Enrico Nicola Mancini in the Little Italy neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio, Henry Mancini was raised in West Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. Though his father wished his son to become a teacher, Mancini was inspired by the music of Hollywood, particularly that of the 1935 Cecil B. DeMille film “The Crusades.” This fascination saw him embark on a lifelong journey into composition. His first instrument of choice was the piccolo, but soon he drifted toward the piano, studying under Pittsburgh concert pianist and Stanley Theatre conductor Max Adkins. Upon graduating high school, Mancini matriculated at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, but quickly transferred to the Julliard School of Music, concentrating his studies in piano, orchestration, and composition. When America entered World War II, Mancini enlisted in the United States Army in 1943. Assigned to the 28th Air Force Band, he made many connections in the music industry that would serve him well in the post-war years. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Putting National Party Convention

CONVENTIONAL WISDOM: PUTTINGNATIONAL PARTY CONVENTION RATINGS IN CONTEXT Jill A. Edy and Miglena Daradanova J&MC This paper places broadcast major party convention ratings in the broad- er context of the changing media environmentfrom 1976 until 2008 in order to explore the decline in audience for the convention. Broadcast convention ratings are contrasted with convention ratingsfor cable news networks, ratings for broadcast entertainment programming, and ratings Q for "event" programming. Relative to audiences for other kinds of pro- gramming, convention audiences remain large, suggesting that profit- making criteria may have distorted representations of the convention audience and views of whether airing the convention remains worth- while. Over 80 percent of households watched the conventions in 1952 and 1960.... During the last two conventions, ratings fell to below 33 percent. The ratings reflect declining involvement in traditional politics.' Oh, come on. At neither convention is any news to be found. The primaries were effectively over several months ago. The public has tuned out the election campaign for a long time now.... Ratings for convention coverage are abysmal. Yet Shales thinks the networks should cover them in the name of good cit- izenship?2 It has become one of the rituals of presidential election years to lament the declining television audience for the major party conven- tions. Scholars like Thomas Patterson have documented year-on-year declines in convention ratings and linked them to declining participation and rising cynicism among citizens, asking what this means for the future of mass dem~cracy.~Journalists, looking at conventions in much the same way, complain that conventions are little more than four-night political infomercials, devoid of news content and therefore boring to audiences and reporters alike.4 Some have suggested that they are no longer worth airing. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

“The Masterpiece” PRODUCTION BIOS MARTHA WILLIAMSON

‘SIGNED, SEALED, DELIVERED’ 1004 “The Masterpiece” PRODUCTION BIOS MARTHA WILLIAMSON (Executive Producer and Creator) - Martha Williamson made television history when her CBS series, "Touched By An Angel" set a new standard for an inspirational family drama when it grew to a weekly audience of 25 million viewers and exploded into more than a billion dollar franchise during its initial 9-year run. As Executive Producer and Head Writer of the ground-breaking series, Williamson was the visionary who guided the show into previously uncharted territory with her unique brand of inspirational story telling that produced more than strong ratings; it changed lives. Correspondence from viewers reveals its continued impact as the series plays in syndication and DVD's worldwide. Williamson then sealed her place in history when she went on to become the first woman to solely executive-produce two one-hour dramas simultaneously, after creating and executive- producing “Promised Land,” which aired for three years on CBS. As the go-to creative executive for inspirational family entertainment, Williamson is consulting with companies that are expanding their brands into the growing genre of faith and family programming. Under her MoonWater Productions banner, she is developing a number of television pilots. Her “Signed, Sealed, Delivered” comic drama is scheduled to air on Hallmark Channel in October 2013. She has also returned to script doctoring and is serving as a Screenwriter and Executive Producer for the remake of Disney's classic family film “Thomasina.” She began her career in comedy, working with the producing teams for Carol Burnett and Joan Rivers and went on to write for and produce situation comedies such as "The Facts of Life," "Family Man," "Jack's Place" and "Living Dolls" for all the networks. -

Gene Kearney Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7d5nf5r2 No online items Finding Aid for the Gene Kearney Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207) Finding aid prepared by J. Vera and J. Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Gene Kearney PASC.207 1 Papers, 1932-1979 (Collection PASC.207) Title: Gene Kearney papers Collection number: PASC.207 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 7.5 linear ft.(15 boxes.) Date (inclusive): 1932-1979 Abstract: Gene Kearney was a writer, director, producer, and actor in various television programs and motion pictures. Collection consists of scripts, production information and clippings related to his career. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Kearney, Gene R Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Portions of this collection are restricted. Consult finding aid for additional information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris, We, the undersigned, are writing to urge your administration to reconsider the United States Army Corps of Engineers’ use of Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP12) to construct large fossil fuel pipelines. In Memphis, Tennessee, this “fast-tracked” permitting process has given the green light to the Byhalia pipeline, despite the process wholly ignoring significant environmental justice issues and the threat the project potentially poses to a local aquifer which provides drinking water to one million people. The pipeline route cuts through a resilient, low-wealth Black community, which has already been burdened by seventeen toxic release inventory facilities. The community suffers cancer rates four times higher than the national average. Subjecting this Black community to the possible health effects of more environmental degradation is wrong. Because your administration has prioritized the creation of environmental justice, we knew knowledge of this project would resonate with you. The pipeline would also cross through a municipal well field that provides the communities drinking water. To add insult to injury, this area poses the highest seismic hazard in the Southeastern United States. The Corps purports to have satisfied all public participation obligations for use of NWP 12 on the Byhalia pipeline in 2016 – years before the pipeline was proposed. We must provide forums where communities in the path of industrial projects across the country can be heard. Neighborhoods like Boxtown and Westwood in Memphis have a right to participate in the creation of their own destinies and should never be ignored. -

ANDY D'addario Re-Recording Mixer

ANDY D'ADDARIO Re-Recording Mixer SOUNDTRACK (PILOT) Joshua Safran Netflix RRM SSE, CRAZY BITCHES Jane Clark FilmMcQueen RRM THE INBETWEEN (2 EPISODES, RRM Moira Kirland NBC SEASON 1) Stephanie Savage/Josh RRM DYNASTY The CW Schwartz THE X FILES Chris Carter Fox Network RRM SSE, BLURT (TV MOVIE) Michelle Johnston Pacific Bay Entertainment RRM MOZART IN THE JUNGLE Alex Timbers Amazon RRM Image not found or type unknown ESCAPE FROM MR. SSE, LEMONCELLO'S LIBRARY (TV Scott McAboy Nickelodeon Network RRM MOVIE) TRANSPARENT Jill Soloway Amazon RRM KINGDOM Byron Balasco DirectTV RRM I LOVE DICK (6 EPISODES, RRM Sarah Gubbins Amazon Studios SEASON 1) IMPOSTERS Paul Adelstein Bravo! RRM SSE, RUFUS-2 (TV MOVIE) Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network RRM LEGENDS OF THE HIDDEN SSE, Joe Menendez Nickelodeon Network TEMPLE (TV MOVIE) RRM SSE, LIAR, LIAR, VAMPIRE (TV MOVIE) Vince Marcello Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, ONE CRAZY CRUISE (TV MOVIE) Michael Grossman Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, SPLITTING ADAM (TV MOVIE) Scott McAboy Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, SANTA HUNTERS (TV MOVIE) Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network RRM A FAIRLY ODD SUMMER (TV SSE, Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network MOVIE) RRM HAWAII FIVE-O Peter M. Lenkov CBS RRM SWINDLE (TV MOVIE) Jonathan Judge Nickelodeon Network RRM Formosa Broadcast www.FormosaGroup.com/Broadcast 323.853.0008 [email protected] Page 1 GOLDEN BOY (PILOT) Nicholas Wootton CBS RRM CSI: NY Ann Donahue CBS RRM SECOND SIGHT (TV MOVIE) Michael Cuesta CBS RRM A FAIRLY ODD CHRISTMAS (TV RRM Savage Steve -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House