To See Music in Your Mind's Eye: the Genesis of Memorization As a Piano Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family-Memoirs – About Strategies of Creating Identity in Vienna of the 1940S

Family-Memoirs – About strategies of creating identity in Vienna of the 1940s. By example of the family of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Nicole L. Immler, University of Graz My talk will be about one of the most quoted sources concerning the biography of the well known austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who studied philosophy in Cambridge and later became professor of philosophy at Trinity- College: The family memoirs written by Hermine Wittgenstein, the sister of the philosopher, in the years 1944–49 in Vienna.1 The Typescript is so far unpublished, with the exception of the section concerning Ludwig Wittgenstein 2, and was never contextualised as a whole. To use the Familienerinnerungen as a historical source it‘s f i r s t l y necessary to picture the relevance of family memoirs from the perspective of recent theories about memory culture. S e c o n d l y it is to ask about the general historical background of the literary genre family memoirs as such, about the intentions and functions of this genre as well as its origin. Specifically related to the Wittgenstein memoirs I want to follow the thesis, if they can be read as an example of a strategy to create identity for a bourgeois family in Vienna in the nineteenforties. Finally and f o u r t h y, I want to ‚proof- read‘ one argument made by Hermine Wittgenstein by comparing it to arguments of Ludwig Wittgenstein in his writings. Owing to their differences in living conditions, character and experiences, they have different approaches towards a geographical and emotional concept of home. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Die „Turnhallenkonzerte“ in Der Fürstlich Waldeckischen Residenzstadt Arolsen Unter Der Leitung Des Militärkapellmeisters Hugo Rothe (1864–1934)

Die „Turnhallenkonzerte“ in der Fürstlich Waldeckischen Residenzstadt Arolsen unter der Leitung des Militärkapellmeisters Hugo Rothe (1864–1934) Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der Verbindung von Militärmusik und musikalischer Volksbildung im Deutschen Kaiserreich Teil 2 Katalog Stand: 03.09.2017 Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg Vorgelegt von Tobias Wunderle aus Berlin 2017 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ....................................................................................................................... 4 Einführung .................................................................................................................. 5 Verzeichnis der Signaturen ......................................................................................... 7 Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen und Siglen ................................................................. 11 R-kl ........................................................................................................................... 12 R-klE ......................................................................................................................... 75 R-gr........................................................................................................................... 78 R-grE ...................................................................................................................... 122 R-So ...................................................................................................................... -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

1 Florestan and Eusebius

FLORESTAN AND EUSEBIUS: A LOOK INTO THE CRITICAL AND CREATIVE MINDSET OF ROBERT SCHUMANN THROUGH THE STUDY OF SELECTED WRITINGS AND FANTASIESTÜCKE OP. 73 FÜR KLAVIER UND KLARINETTE By Lauren Bailey Lewis A Senior Honors Project Presented to the Honors College East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Lauren Bailey Lewis Greenville, NC May, 2018 Approved by: Dr. Douglas Moore-Monroe Associate Professor of Clarinet, School of Music, College of Fine Arts and Communication 1 Robert Schumann was an extremely influential composer and music critic during the Romantic era. Recognized for his strong connection between literature and music, musicians remember Schumann as one of the great composers of the nineteenth century. As the editor of Neue Zeitschift für Musik (New Periodical for Music) for ten years, Schumann wrote various articles critiquing distinguished and rising composers based on both technical and expressive elements in their music. Often, Schumann offered his critique through three separate characters: Eusebius, Florestan, and Master Raro. Entertaining and story-like, these character portrayals envelope aspects of Schumann’s personality and compositional style. For example, Florestan’s character is passionate, exuberant, and sometimes impulsive. On the other hand, Eusebius represents a thoughtful and reflective approach to criticism. He acts as a dreamer or romantic, and usually leaves some positive remark. These two contrasting characters are both used to describe music composed in the mid to late 1800’s. Florestan and Eusebius address separate issues and contribute to a rich understanding of the music through Schumann’s critique. Master Raro often synthesizes these conclusions into one digestible object, combining the technical and expressive elements of music. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” Concert and Lecture Series

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 5-2-1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848,” for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series. The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, , : , 1998. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © David B. Dennis 1998 “Robert Schumann and the German Revolution of 1848” David B. Dennis Paper for “Music and Revolution,” concert and lecture series arranged by The American Bach Project and supported by the Wisconsin Humanities Council as part of the State of Wisconsin Sesquicentennial Observances, All Saints Cathedral Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2 May 1998. 1 Let me open by thanking Alexander Platt and Joan Parsley of Ensemble Musical Offering, for inviting me to speak with you tonight. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions Ignat Drozdov, BS, Mark Kidd, PhD, Irvin M. Modlin, MD, PhD Electronic searches were performed to investigate the evolution of one-handed piano com- positions and one-handed music techniques, and to identify individuals responsible for the development of music meant for playing with one hand. Particularly, composers such as Liszt, Ravel, Scriabin, and Prokofiev established a new model in music by writing works to meet the demands of a variety of pianist-amputees that included Count Géza Zichy (1849– 1924), Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), and Siegfried Rapp (b. 1915). Zichy was the first to amplify the scope of the repertoire to improve the variety of one-handed music; Wittgenstein developed and adapted specific and novel performance techniques to accommodate one- handedness; and Rapp sought to promote the stature of one-handed pianists among a musically sophisticated public able to appreciate the nuances of such maestros. (J Hand Surg 2008;33A:780–786. Copyright © 2008 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. All rights reserved.) Key words Amputation, hand, history of surgery, music, piano. UCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT the creativity of EVOLUTION OF THE PIANO: OF FINGERS AND composers and the skills of musicians, and KEYS Mspecial emphases have been placed on the Pianists are graced with a rich and remarkable history of mind and the vagaries of neurosis and even madness in their instrument, which encompasses more than 850 the process of composition. Little consideration has years of development and evolution.1 From the keyed been given to physical defects and their influence on monochord in 1157, to the clavichord (late Medieval), both music and its interpretation. -

Wittgenstein's Vienna Our Aim Is, by Academic Standards, a Radical One : to Use Each of Our Four Topics As a Mirror in Which to Reflect and to Study All the Others

TOUCHSTONE Gustav Klimt, from Ver Sacrum Wittgenstein' s VIENNA Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin TOUCHSTONE A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster Copyright ® 1973 by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster A Division of Gulf & Western Corporation Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 TOUCHSTONE and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster ISBN o-671-2136()-1 ISBN o-671-21725-9Pbk. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-83932 Designed by Eve Metz Manufactured in the United States of America 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The publishers wish to thank the following for permission to repro duce photographs: Bettmann Archives, Art Forum, du magazine, and the National Library of Austria. For permission to reproduce a portion of Arnold SchOnberg's Verklarte Nacht, our thanks to As sociated Music Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., copyright by Bel mont Music, Los Angeles, California. Contents PREFACE 9 1. Introduction: PROBLEMS AND METHODS 13 2. Habsburg Vienna: CITY OF PARADOXES 33 The Ambiguity of Viennese Life The Habsburg Hausmacht: Francis I The Cilli Affair Francis Joseph The Character of the Viennese Bourgeoisie The Home and Family Life-The Role of the Press The Position of Women-The Failure of Liberalism The Conditions of Working-Class Life : The Housing Problem Viktor Adler and Austrian Social Democracy Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party Georg von Schonerer and the German Nationalist Party Theodor Herzl and Zionism The Redl Affair Arthur Schnitzler's Literary Diagnosis of the Viennese Malaise Suicide inVienna 3. -

TOCC0500DIGIBKLT.Pdf

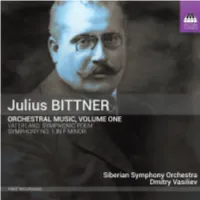

JULIUS BITTNER, FORGOTTEN ROMANTIC by Brendan G. Carroll Julius Bittner is one of music’s forgotten Romantics: his richly melodious works are never performed today and he is perhaps the last major composer of the early twentieth century to have been entirely ignored by the recording industry – until now: apart from four songs, this release marks the very first recording of any of his music in modern times. It reveals yet another colourful and individual voice among the many who came to prominence in the period before the First World War – and yet Bittner, an important and integral part of Viennese musical life before the Nazi Anschluss of 1938 subsumed Austria into the German Reich, was once one of the most frequently performed composers of contemporary opera in Austria. He wrote in a fluent, accessible and resolutely tonal style, with an undeniable melodic gift and a real flair for the stage. Bittner was born in Vienna on 9 April 1874, the same year as Franz Schmidt and Arnold Schoenberg. Both of his parents were musical, and he grew up in a cultured, middle-class home where artists and musicians were always welcomed (Brahms was a friend of the family). His father was a lawyer and later a distinguished judge, and initially young Julius followed his father into the legal profession, graduating with honours and eventually serving as a senior member of the judiciary throughout Lower Austria, until 1920. He subsequently became an important official in the Austrian Department of Justice, until ill health in the mid-1920s forced him to retire (he was diabetic).