Porrajmos. Constructing Gypsy Holocaust Memory in the Recent Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded From

K. Bilby How the ýolder headsý talk: a Jamaican Maroon spirit possession language and its relationship to the creoles of Suriname and Sierra Leone In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 57 (1983), no: 1/2, Leiden, 37-88 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 11:19:53AM via free access 37 KENNETH M. BILBY HOW THE "OLDER HEADS" TALK: A JAMAICAN MAROON SPIRIT POSSESSION LANGUAGE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE CREOLES OF SURINAME AND SIERRA LEONE Introduction 37 The meaning of 'deep' language 39 Some distinctive characteristics of'deep' language 42 The question of preservation 56 Historical questions 59 Notes 62 Appendix A-C 70 References 86 In the interior of Jamaica exist four major Maroon communities, inhabited by the descendants of slaves who escaped from planta- tions during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and gained their freedom by treaty in 1739. The present-day Maroon settle- ments — Moore Town, Charles Town, and Scott's Hall in the east, and Accompong in the west — are now nearly indistin- guishable, on the surface, from other rural Jamaican villages.1 Among the things which continue to set the Maroons apart from their non-Maroon neighbors are a number of linguistic features which appear to be found only in Maroon areas. The Maroon settlements have been described by two leading authorities as "centres of linguistic conservatism" (Cassidy & Le Page 1980: xli); but very little substantial documentation has yet appeared in print to back up this claim.2 While conducting an ethnographic study among the Jamaican Maroons in 1977-8,1 encountered a number of complex linguistic phenomena which were closely tied to the traditional ceremonial sphere in the various communities. -

Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Roma and Sinti Under-Studied Victims of Nazism Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2002 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, July 2004 Copyright © 2002 by Ian Hancock, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Michael Zimmermann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Guenter Lewy, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Mark Biondich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Denis Peschanski, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by Viorel Achim, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2002 by David M. Crowe, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................i Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich Romani Americans (“Gypsies”).......................................................................................................1 Ian -

Extracted from We Are the Romani People, Chapter 4

Extracted from We Are the Romani People, Chapter 4 ROMANIES AND THE HOLOCAUST: A REEVALUATION AND AN OVERVIEW Ian Hancock --------------- "It was the wish of the all-powerful Reichsfuhrer Adolf Hitler to have the Gypsies disappear from the face of the earth" (SS Officer Percy Broad, Auschwitz Political Division)1 "The motives invoked to justify the death of the Gypsies were the same as those ordering the murder of the Jews, and the methods employed for the one were identical with those employed for the other" (Miriam Novitch, Ghetto Fighters' House, Israel)2 "The genocide of the Sinti and Roma was carried out from the same motive of racial mania, with the same premeditation, with the same wish for the systematic and total extermination as the genocide of the Jews. Complete families from the very young to the very old were systematically murdered within the entire sphere of influence of the National Socialists" (Roman Herzog, Federal President of Germany, 16 March 1997) Miriam Novitch refers above to the motives put forth to justify the murder of the Romanies, or "Gypsies," in the Holocaust, though in her small but groundbreaking book she is only partly right: both Jews and Romanies did indeed share the common status- along with the handicapped- of being targeted for elimination because of the threat they were perceived to pose to the pristine gene-pool of the German Herrenvolk or "Master Race;" but while the Jews were considered a threat on a number of other grounds as well, political, philosophical and economic, the Romanies were only ever a "racial" threat. -

The Romani Holocaust Ian Hancock

| 1 Zagreb May 2013 O Porrajmos: The Romani Holocaust Ian Hancock To understand why Hitler sought to eradicate the Romanies, a people who presented no problem numerically, politically, militarily or economically, one must interpret the underlying rationale of the holocaust as being his attempt to create a superior Germanic population, a Master Race, by eliminating what he viewed as genetic pollutants in the Nordic gene pool, and why he believed that Romanies constituted such contamination. The holocaust itself was the implementation of his Final Solution, the genocidal program intended to accomplish this vision of ethnic cleansing. Just two “racial” populations defined by what they were born were thus targeted: the Jews and the Romanies1. The very inventor of the term, Raphael Lemkin, referred to the genocide of the “gypsies” even before the Second World War was over2. It is also essential to place the holocaust of the Romanies3 in its historical context. For perhaps most Romanies today it lacks the special place it holds for Jews, being seen as just one more hate-motivated crisis— albeit an overwhelmingly terrible one—in their overall European experience. Others refuse to speak about it because of its association with death and misfortune, or to testify or accept reparation for the same reason. The first German anti-Romani law was issued in 1416 when they were accused of being foreign spies, carriers of the plague, and traitors to Christendom; In 1500 Maximilian I ordered all to be out of Germany by Easter; Ferdinand I enforced expulsion -

A Film by Tony Gatlif

A FILM BY TONY GATLIF – 1 – – 1 – PRINCES PRODUCTION presents DAPHNÉ PATAKIA INTERNATIONAL SALES - LES FILMS DU LOSANGE : BÉRÉNICE VINCENT / LAURE PARLEANI / LISE ZIPCI / JULES CHEVALIER SIMON ABKARIAN 22, Avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie - 75016 Paris MARYNE CAYON Tél. : +33 1 44 43 87 13 / 24 / 28 Bérénice Vincent: +33 6 63 74 69 10 / [email protected] Laure Parleani: +33 6 84 21 74 53 / [email protected] Lise Zipci: +33 6 75 13 05 75 / [email protected] Jules Chevalier: +33 6 84 21 74 47 / [email protected] in Cannes: Riviera - Stand J7 PRESSE: BARBARA VAN LOMBEEK www.theprfactory.com [email protected] A FILM BY TONY GATLIF Photos and press pack can be downloaded at www.filmsdulosange.fr FRANCE • 2017 • 97MN • COLOR • FORMAT 1.50 • SOUND 5.1 – 2 – JAM, a young Greek woman, is sent to Istanbul by her uncle Kakourgos, a former sailor and passionate fan of Rebetiko, on a mission to find a rare engine part for their boat. There she meets Avril, 18, who came from France to volunteer with refugees, ran out of money, and knows no one in Turkey. Generous, sassy, unpredictable and free, Djam takes Avril under her wing on the way to Mytilene—a journey made of music, encounters, sharing and hope. – 4 – – 5 – Where did the idea for this film come from? Why make a film about this style of music, From Rebetiko music, which I discovered in 1983 on and why now? a trip to Turkey to introduce a screening of my film Les Because its songs are songs of exile: the Greeks’ Princes. -

Pidgin and Creole Languages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke

Pidgin and Creole Languages JOHN E. REINECKE 1904–1982 Pidgin and Creole Languages Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke Edited by Glenn G. Gilbert Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882150 (PDF) 9780824882143 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1987 University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Preface viii Acknowledgments xii Introduction 1 John E. Reinecke: His Life and Work Charlene J. Sato and Aiko T. Reinecke 3 William Greenfield, A Neglected Pioneer Creolist John E. Reinecke 28 Theoretical Perspectives 39 Some Possible African Creoles: A Pilot Study M. Lionel Bender 41 Pidgin Hawaiian Derek Bickerton and William H. Wilson 65 The Substance of Creole Studies: A Reappraisal Lawrence D. Carrington 83 Verb Fronting in Creole: Transmission or Bioprogram? Chris Corne 102 The Need for a Multidimensional Model Robert B. Le Page 125 Decreolization Paths for Guyanese Singular Pronouns John R. -

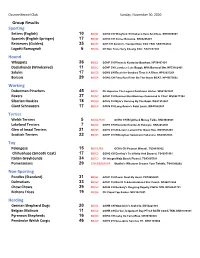

Group Results Sporting Hound Working Terrier Toy Non‐Sporting

Oconee Kennel Club Sunday, November 30, 2020 Group Results Sporting Setters (English) 10 BB/G1 GCHG CH Wingfield 'N Chebaco Here And Now. SR92506801 Spaniels (English Springer) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza. SR89255201 Retrievers (Golden) 35 BB/G3 GCH CH Gemini's Tranquil Rain CGC TKN. SR99164302 Lagotti Romagnoli 6 BB/G4 CH Kan Trace Very Cheeky Chic. SS07657803 Hound Whippets 36 BB/G1 GCHP CH Pinnacle Kentucky Bourbon. HP50403101 Dachshunds (Wirehaired) 11 BB/G2 GCHP CH Leoralees Lets Boogie With Barstool Mw. HP53162401 Salukis 17 BB/G3 GCHS CH Excelsior Sundara Time Is A River. HP52037201 Borzois 29 BB/G4 GCHG CH Fiery Run Rider On The Storm BCAT. HP49675002 Working Doberman Pinschers 45 BB/G1 CH Aquarius The Legend Continues Alcher. WS61281801 Boxers 37 BB/G2 GCHP CH Rummer Run Maximus Command In Chief. WS59471304 Siberian Huskies 18 BB/G3 GCHS CH Myla's Dancing By The Book. WS51910901 Giant Schnauzers 17 BB/G4 GCHS CH Long Grove's Saint Louis. WS53602903 Terrier Welsh Terriers 5 BB/G1/RBIS GCHG CH Brightluck Money Talks. RN29480501 Lakeland Terriers 7 BB/G2 GCHS CH Ellenside Red Ike At Eskwyre. RN32452601 Glen of Imaal Terriers 21 BB/G3 GCHS CH Abberann Lament For Owen Roe. RN30563209 Scottish Terriers 22 BB/G4 GCHP CH Whiskybae Haslemere Habanera. RN29251603 Toy Pekingese 15 BB/G1/BIS GCHS CH Pequest Wasabi. TS38696002 Chihuahuas (Smooth Coat) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Destiny's To Infinity And Beyond. TS46951901 Italian Greyhounds 34 BB/G3 CH Integra Maja Beach Please!. TS43095301 Pomeranians 29 1/W/BB/BW/G4 Starfire's Whatever Creams Your Twinkie. -

Listeréalisateurs

A Crossing the bridge : the sound of Istanbul (id.) 7-12 De lʼautre côté (Auf der anderen Seite) 14-14 DANIEL VON AARBURG voir sous VON New York, I love you (id.) 10-14 DOUGLAS AARNIOKOSKI Sibel, mon amour - head-on (Gegen die Wand) 16-16 Highlander : endgame (id.) 14-14 Soul kitchen (id.) 12-14 PAUL AARON MOUSTAPHA AKKAD Maxie 14 Le lion du désert (Lion of the desert) 16 DODO ABASHIDZE FEO ALADAG La légende de la forteresse de Souram Lʼétrangère (Die Fremde) 12-14 (Ambavi Suramis tsikhitsa - Legenda o Suramskoi kreposti) 12 MIGUEL ALBALADEJO SAMIR ABDALLAH Cachorro 16-16 Écrivains des frontières - Un voyage en Palestine(s) 16-16 ALAN ALDA MOSHEN ABDOLVAHAB Les quatre saisons (The four seasons) 16 Mainline (Khoon Bazi) 16-16 Sweet liberty (id.) 10 ERNEST ABDYJAPOROV PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON voir sous ROBINSON Pure coolness - Pure froideur (Boz salkyn) 16-16 ROBERT ALDRICH Saratan (id.) 10-14 Deux filles au tapis (The California Dolls - ... All the marbles) 14 DOMINIQUE ABEL TOMÁS GUTIÉRREZ ALEA voir sous GUTIÉRREZ La fée 7-10 Rumba 7-14 PATRICK ALESSANDRIN 15 août 12-16 TONY ABOYANTZ Banlieue 13 - Ultimatum 14-14 Le gendarme et les gendarmettes 10 Mauvais esprit 12-14 JIM ABRAHAMS DANIEL ALFREDSON Hot shots ! (id.) 10 Millenium 2 - La fille qui rêvait dʼun bidon dʼessence Hot shots ! 2 (Hot shots ! Part deux) 12 et dʼune allumette (Flickan som lekte med elden) 16-16 Le prince de Sicile (Jane Austenʼs mafia ! - Mafia) 12-16 Millenium 3 - La reine dans le palais des courants dʼair (Luftslottet som sprangdes) 16-16 Top secret ! (id.) 12 Y a-t-il quelquʼun pour tuer ma femme ? (Ruthless people) 14 TOMAS ALFREDSON Y a-t-il un pilote dans lʼavion ? (Airplane ! - Flying high) 12 La taupe (Tinker tailor soldier spy) 14-14 FABIENNE ABRAMOVICH JAMES ALGAR Liens de sang 7-14 Fantasia 2000 (id. -

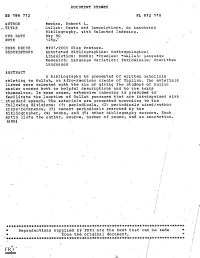

Gullah: Texts and Descriptions

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 198 712 FL 012 1,18 AUTHOR Meehan, Robert L. Gullah: Texts and Descriptions. An Annotated Bibliography, with Selected Indexing. PUB DATE May BO NOTE 125p. EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies: Anthropological Linguistics: Books; *Creoles: * Gullah; Language Research: Language Variation; Periodicals: Unwritten Languages ABSTRACT A bibli3Ography Js presented of written mtterials. relating6 to Gullah, an Afro-American creole of English_ The materials listed were selected with the aim of giving the student of Gullah easier access both to helpful descriptions and to the texts themselves. In Some cases, extensive indexing is provided to- faCilitate the location of Gullah passages that are interspersed with -7:istanderd speech._The_caterials are presented!according_to the following divisions: (1)-periodicals,(2) periodicals cited/author cross:.reference-,(3) recent periodicals Searched by: the .bibliographer, (4)books,.-and (5) other bibliography sources. Each. entry lists the authorsource, number of pages, and an annotation . '(AMH) ***************************************************.******************** * Reproductions supplied by'EDRS are the best that can ibe made from the original document. '°4********************************************************************** GULLAH:- TEXT'S AND,DESCR1RTIONSI An Annotated Bibliography, With Selective IndeScing Robert Meehan UICC May 20, 1980 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL -

Wandering Memories

WANDERING MEMORIES MARGINALIZING AND REMEMBERING THE PORRAJMOS Research Master Thesis Comparative Literary Studies Talitha Hunnik August 2015 Utrecht University Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Susanne Knittel Second Reader: Prof. Dr. Ann Rigney CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 3 A Note on Terminology ...................................................................................................................... 4 A Note on Translations ...................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Antiziganism and the Porrajmos ................................................................................................. 8 Wandering Memories ................................................................................................................. 12 Marginalized Memories: Forgetting the Porrajmos ......................................................... 19 Cultural Memory Studies: Concepts and Gaps ........................................................................ 24 Walls of Secrecy ........................................................................................................................... 34 Remembering the Holocaust and Marginalizing the Porrajmos ........................................ -

Re-Remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia

Re-remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia by Maria Konstantinov BFA, University of Victoria, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program © Maria Konstantinov, 2015 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Re-remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia by Maria Konstantinov BFA, University of Victoria, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Serhy Yekelchyk, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Co-Supervisor Dr. Margot Wilson, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Serhy Yekelchyk, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Co-Supervisor Dr. Margot Wilson, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor This thesis explores the ways in which the Holocaust experiences and memories of Roma communities in post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia have been both remembered and forgotten. In these nations, the Porraimos, meaning the “Great Devouring” in some Romani dialects, has been largely silenced by the politics of national memory, and by the societal discrimination and ostracization of Roma communities. While Ukraine has made strides towards memorializing Porraimos in the last few decades, the Russian state has yet to do the same. I question how experiences of the Porraimos fit into Holocaust memory in these nations, why the memorialization of the Porraimos is important, what the relationship between communal and public memory is, and lastly, how communal Roma memory is instrumental in reshaping the public memory of the Holocaust. -

Curriculum Vitæ

1 Curriculum Vitæ A. Personal Ian Francis Hancock (o Yanko le Redjosko) Born: London, England; US/UK/EC Citizen Marrried: Wife: Denise Davis Five children: (Marko, Imre, Melina, Malik, Chloë) Addresses: Home: Amari Avlin 58 Country Oaks Drive Buda, TX 78610-9338 Tel: (512)-295-4848 E-Mail: [email protected] Work: Department of Linguistics The University of Texas B5100 Austin, Texas 78712 512-471-1701 Department of English Parlin Hall The University of Texas B5000 Austin, Texas 78712 512-471-4991 The Romani Archives and Documentation Center Parlin Hall The University of Texas B5000 Austin, Texas 78712 512-232-7684 Fax: 512-295-7733 B. Academic and Administrative Involvement a. Education: Ph.D. (honoris causa) with distinction, awarded by Umeå University, Sweden, October, 2005. Ph.D. (honoris causa) awarded by Constantine University, Slovakia, November 2009. Ph.D. awarded by London University, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1971. b. Academic Positions: 2 Director, The Romani Archives and Documentation Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Nowlin Regents Professor in Liberal Arts since 2005. Professor (since 1984) in the Departments of Linguistics and English. Minority faculty member. Associate Professor, 1977-1983. Assistant Professor, 1972-1976. Honorary Vice-Chancellor, Sabhyata Sanskriti Roma University, New Delhi, 2012- External Examiner, Faculty of Arts & General Studies, The University of the West Indies (all campuses: Trinidad, Barbados, Jamaica), 1982-1998. Co-founder/co-editor, International Journal of Romani Language and Culture (Lincom: Berlin, 2009-) c. Service and Other Academic Work (past and present): Member, Faculty Council, 2006-2008 Member, Rapoport Center for Human Rights, 2006-2011 (UTA) Member, Center for European Studies, 2005- (UTA) Member, International Leadership Program, annually hosting European visitors to the Archives.