A Note on the Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Film by Tony Gatlif

A FILM BY TONY GATLIF – 1 – – 1 – PRINCES PRODUCTION presents DAPHNÉ PATAKIA INTERNATIONAL SALES - LES FILMS DU LOSANGE : BÉRÉNICE VINCENT / LAURE PARLEANI / LISE ZIPCI / JULES CHEVALIER SIMON ABKARIAN 22, Avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie - 75016 Paris MARYNE CAYON Tél. : +33 1 44 43 87 13 / 24 / 28 Bérénice Vincent: +33 6 63 74 69 10 / [email protected] Laure Parleani: +33 6 84 21 74 53 / [email protected] Lise Zipci: +33 6 75 13 05 75 / [email protected] Jules Chevalier: +33 6 84 21 74 47 / [email protected] in Cannes: Riviera - Stand J7 PRESSE: BARBARA VAN LOMBEEK www.theprfactory.com [email protected] A FILM BY TONY GATLIF Photos and press pack can be downloaded at www.filmsdulosange.fr FRANCE • 2017 • 97MN • COLOR • FORMAT 1.50 • SOUND 5.1 – 2 – JAM, a young Greek woman, is sent to Istanbul by her uncle Kakourgos, a former sailor and passionate fan of Rebetiko, on a mission to find a rare engine part for their boat. There she meets Avril, 18, who came from France to volunteer with refugees, ran out of money, and knows no one in Turkey. Generous, sassy, unpredictable and free, Djam takes Avril under her wing on the way to Mytilene—a journey made of music, encounters, sharing and hope. – 4 – – 5 – Where did the idea for this film come from? Why make a film about this style of music, From Rebetiko music, which I discovered in 1983 on and why now? a trip to Turkey to introduce a screening of my film Les Because its songs are songs of exile: the Greeks’ Princes. -

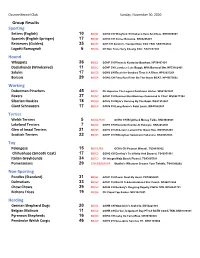

Group Results Sporting Hound Working Terrier Toy Non‐Sporting

Oconee Kennel Club Sunday, November 30, 2020 Group Results Sporting Setters (English) 10 BB/G1 GCHG CH Wingfield 'N Chebaco Here And Now. SR92506801 Spaniels (English Springer) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Cerise Bonanza. SR89255201 Retrievers (Golden) 35 BB/G3 GCH CH Gemini's Tranquil Rain CGC TKN. SR99164302 Lagotti Romagnoli 6 BB/G4 CH Kan Trace Very Cheeky Chic. SS07657803 Hound Whippets 36 BB/G1 GCHP CH Pinnacle Kentucky Bourbon. HP50403101 Dachshunds (Wirehaired) 11 BB/G2 GCHP CH Leoralees Lets Boogie With Barstool Mw. HP53162401 Salukis 17 BB/G3 GCHS CH Excelsior Sundara Time Is A River. HP52037201 Borzois 29 BB/G4 GCHG CH Fiery Run Rider On The Storm BCAT. HP49675002 Working Doberman Pinschers 45 BB/G1 CH Aquarius The Legend Continues Alcher. WS61281801 Boxers 37 BB/G2 GCHP CH Rummer Run Maximus Command In Chief. WS59471304 Siberian Huskies 18 BB/G3 GCHS CH Myla's Dancing By The Book. WS51910901 Giant Schnauzers 17 BB/G4 GCHS CH Long Grove's Saint Louis. WS53602903 Terrier Welsh Terriers 5 BB/G1/RBIS GCHG CH Brightluck Money Talks. RN29480501 Lakeland Terriers 7 BB/G2 GCHS CH Ellenside Red Ike At Eskwyre. RN32452601 Glen of Imaal Terriers 21 BB/G3 GCHS CH Abberann Lament For Owen Roe. RN30563209 Scottish Terriers 22 BB/G4 GCHP CH Whiskybae Haslemere Habanera. RN29251603 Toy Pekingese 15 BB/G1/BIS GCHS CH Pequest Wasabi. TS38696002 Chihuahuas (Smooth Coat) 17 BB/G2 GCHG CH Destiny's To Infinity And Beyond. TS46951901 Italian Greyhounds 34 BB/G3 CH Integra Maja Beach Please!. TS43095301 Pomeranians 29 1/W/BB/BW/G4 Starfire's Whatever Creams Your Twinkie. -

Listeréalisateurs

A Crossing the bridge : the sound of Istanbul (id.) 7-12 De lʼautre côté (Auf der anderen Seite) 14-14 DANIEL VON AARBURG voir sous VON New York, I love you (id.) 10-14 DOUGLAS AARNIOKOSKI Sibel, mon amour - head-on (Gegen die Wand) 16-16 Highlander : endgame (id.) 14-14 Soul kitchen (id.) 12-14 PAUL AARON MOUSTAPHA AKKAD Maxie 14 Le lion du désert (Lion of the desert) 16 DODO ABASHIDZE FEO ALADAG La légende de la forteresse de Souram Lʼétrangère (Die Fremde) 12-14 (Ambavi Suramis tsikhitsa - Legenda o Suramskoi kreposti) 12 MIGUEL ALBALADEJO SAMIR ABDALLAH Cachorro 16-16 Écrivains des frontières - Un voyage en Palestine(s) 16-16 ALAN ALDA MOSHEN ABDOLVAHAB Les quatre saisons (The four seasons) 16 Mainline (Khoon Bazi) 16-16 Sweet liberty (id.) 10 ERNEST ABDYJAPOROV PHIL ALDEN ROBINSON voir sous ROBINSON Pure coolness - Pure froideur (Boz salkyn) 16-16 ROBERT ALDRICH Saratan (id.) 10-14 Deux filles au tapis (The California Dolls - ... All the marbles) 14 DOMINIQUE ABEL TOMÁS GUTIÉRREZ ALEA voir sous GUTIÉRREZ La fée 7-10 Rumba 7-14 PATRICK ALESSANDRIN 15 août 12-16 TONY ABOYANTZ Banlieue 13 - Ultimatum 14-14 Le gendarme et les gendarmettes 10 Mauvais esprit 12-14 JIM ABRAHAMS DANIEL ALFREDSON Hot shots ! (id.) 10 Millenium 2 - La fille qui rêvait dʼun bidon dʼessence Hot shots ! 2 (Hot shots ! Part deux) 12 et dʼune allumette (Flickan som lekte med elden) 16-16 Le prince de Sicile (Jane Austenʼs mafia ! - Mafia) 12-16 Millenium 3 - La reine dans le palais des courants dʼair (Luftslottet som sprangdes) 16-16 Top secret ! (id.) 12 Y a-t-il quelquʼun pour tuer ma femme ? (Ruthless people) 14 TOMAS ALFREDSON Y a-t-il un pilote dans lʼavion ? (Airplane ! - Flying high) 12 La taupe (Tinker tailor soldier spy) 14-14 FABIENNE ABRAMOVICH JAMES ALGAR Liens de sang 7-14 Fantasia 2000 (id. -

Wandering Memories

WANDERING MEMORIES MARGINALIZING AND REMEMBERING THE PORRAJMOS Research Master Thesis Comparative Literary Studies Talitha Hunnik August 2015 Utrecht University Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Susanne Knittel Second Reader: Prof. Dr. Ann Rigney CONTENTS Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 3 A Note on Terminology ...................................................................................................................... 4 A Note on Translations ...................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Antiziganism and the Porrajmos ................................................................................................. 8 Wandering Memories ................................................................................................................. 12 Marginalized Memories: Forgetting the Porrajmos ......................................................... 19 Cultural Memory Studies: Concepts and Gaps ........................................................................ 24 Walls of Secrecy ........................................................................................................................... 34 Remembering the Holocaust and Marginalizing the Porrajmos ........................................ -

Re-Remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia

Re-remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia by Maria Konstantinov BFA, University of Victoria, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program © Maria Konstantinov, 2015 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Re-remembering Porraimos: Memories of the Roma Holocaust in Post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia by Maria Konstantinov BFA, University of Victoria, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Serhy Yekelchyk, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Co-Supervisor Dr. Margot Wilson, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Serhy Yekelchyk, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Co-Supervisor Dr. Margot Wilson, Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor This thesis explores the ways in which the Holocaust experiences and memories of Roma communities in post-Socialist Ukraine and Russia have been both remembered and forgotten. In these nations, the Porraimos, meaning the “Great Devouring” in some Romani dialects, has been largely silenced by the politics of national memory, and by the societal discrimination and ostracization of Roma communities. While Ukraine has made strides towards memorializing Porraimos in the last few decades, the Russian state has yet to do the same. I question how experiences of the Porraimos fit into Holocaust memory in these nations, why the memorialization of the Porraimos is important, what the relationship between communal and public memory is, and lastly, how communal Roma memory is instrumental in reshaping the public memory of the Holocaust. -

TAL Direct: Sub-Index S912c Index for ASIC

TAL.500.002.0503 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Appendix B: Reference to xv: A list of television programs during which TAL’s InsuranceLine Funeral Plan advertisements were aired. 1 90802531/v1 TAL.500.002.0504 TAL Direct: Sub-Index s912C Index for ASIC Section 1_xv List of TV programs FIFA Futbol Mundial 21 Jump Street 7Mate Movie: Charge Of The #NOWPLAYINGV 24 Hour Party Paramedics Light Brigade (M-v) $#*! My Dad Says 24 HOURS AFTER: ASTEROID 7Mate Movie: Duel At Diablo (PG-v a) 10 BIGGEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW IMPACT 7Mate Movie: Red Dawn (M-v l) 10 CELEBRITY REHABS EXPOSED 24 hours of le mans 7Mate Movie: The Mechanic (M- 10 HOTTEST TRACKS RIGHT NOW 24 Hours To Kill v a l) 10 Things You Need to Know 25 Most Memorable Swimsuit Mom 7Mate Movie: Touching The Void 10 Ways To Improve The Value O 25 Most Sensational Holly Melt -CC- (M-l) 10 Years Younger 28 Days in Rehab 7Mate Movie: Two For The 10 Years Younger In 10 Days Money -CC- (M-l s) 30 Minute Menu 10 Years Younger UK 7Mate Movie: Von Richthofen 30 Most Outrageous Feuds 10.5 Apocalypse And Brown (PG-v l) 3000 Miles To Graceland 100 Greatest Discoveries 7th Heaven 30M Series/Special 1000 WAYS TO DIE 7Two Afternoon Movie: 3rd Rock from the Sun 1066 WHEN THREE TRIBES WENT 7Two Afternoon Movie: Living F 3S at 3 TO 7Two Afternoon Movie: 4 FOR TEXAS 1066: The Year that Changed th Submarin 112 Emergency 4 INGREDIENTS 7TWO Classic Movie 12 Disney Tv Movies 40 Smokin On Set Hookups 7Two Late Arvo Movie: Columbo: 1421 THE YEAR CHINA 48 Hour Film Project Swan Song (PG) DISCOVERED 48 -

Romani Mobile Subjectivities and the State: Intersectionality, Genres, and Human Rights

ROMANI MOBILE SUBJECTIVITIES AND THE STATE: INTERSECTIONALITY, GENRES, AND HUMAN RIGHTS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE OFFICE OF GRADUATE EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE July 2018 By Bettina J. Brown Dissertation Committee: Michael J. Shapiro Kathy E. Ferguson Nevzat Soguk Wimal Dissanayake Robert Perkinson Keywords: Romani, intersectionality, genres, human rights, European Union Acknowledgments Diverse, pluralizing Romani articulations guide and inform Romani Mobile Subjectivities and the State: Intersectionality, Genres, and Human Rights. This dissertation presents a mosaic of Romani people, place, time, and movement. I want to note my heartfelt appreciation to all at the Documentation and Cultural Center of German Sinti and Roma, in Heidelberg, and to the many who assisted at numerous source sites in Germany and the United Kingdom, during this doctoral work. Thank you, to my advisor, Michael J. Shapiro, scholarship giant, for your kindness and inspiration, support and gentle patience. You gave me the opportunity to make this dissertation possible. I am eternally grateful. Thank you, Kathy E. Ferguson, for your scholarship among earthlings, helping to inform this dissertation and its title, and all your support. I am eternally grateful. Thank you, Nevzat Soguk, for your scholarship on communities displaced by hegemony, graciously serving on my committee, and your insightful support. Thank you, Wimal Dissanayake, for your scholarship on how worlds world, introducing me to Cultural Studies, and your helpful feedback. Thank you, Robert Perkinson, for your scholarship on civil rights, the incarceration industry, and your thoughtful encouragement. -

FILMFEST DC APRIL 7 – 17, 2011 WASHINGTON DC INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Welcome to Filmfest DC! a World of Stories

An Advertising Supplement to The Washington Post 25TH ANNUAL FILMFEST DC APRIL 7 – 17, 2011 WASHINGTON DC INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL WELCOME TO FILMFEST DC! A world of Stories... a world of filmmakers… Welcome to the 25th anniversary of Filmfest DC... for people who love movies! We are proud to reach this quarter-century landmark of introducing Washington, DC to the consistently Photo: Chad Evans Wyatt Chad Evans Photo: provocative and innovative films of international cinema. Filmmakers are storytellers — and what rich stories they have to tell! This year we have an extraordinary array of films from Scandinavia to South Korea and from Italy to Iran. They all tell us stories that perplex us with life’s riddles, dazzle us with color and song, and inspire us with quiet dignity, grace, and beauty. They let us peer into the seductive world of Spanish flamenco dance, the psyche of a Corsican hotel maid hooked on chess, the innocence of Danish recruits negotiating the battlefields of Afghanistan, the longing of the young Indian woman in search of her father, the adrenaline rush of the Austrian marathoner who robs bank as a hobby — and that’s just a small taste of the richness and variety of this year’s films! Once again, I would like to thank the many dedicated people who have shared their time and talents with Filmfest DC. The University of the District of Columbia is our major sponsor. Filmfest DC greatly appreciates the generous contributions of all our sponsors, patrons, numerous volunteers, local businesses, and diplomatic community. Their support is vital to the festival’s success and shows the enduring contribution the festival makes to our city’s cultural space. -

FOREIGN Dvds – As of July 2014

FOREIGN DVDs – as of July 2014 NRA Adrift (SDH) R After the wedding (SDH) NRA Ajami (SDH) NRA Alain Resnais: A decade in film (4v) NRA Alamar (CC) NRA Alambrista NRA Alexandra NRA Alice’s house NRA All my loved ones NRA All together NRA Almost peaceful NRA Alois Nebel NRA Altiplano NRA Amador (CC) NRA Amantes NRA Amarcord (2v) R Amelie (2v) (CC) R Amores perros (CC) PG-13 Amour R Angela NRA Anita NRA Anthony: Warrior of God R The apartment R Apocalypto (SDH) R Applause R Apres vous NRA Army of crime NRA Army of shadows (2v) NRA Around a small mountain R The artist and the model NRA As it is in heaven NRA As luck would have it (SDH) NRA El Asaltante R At the gate of the ghost (SDH) NRA L’Atalante R The attack R Attack on Leningrad NRA The attorney NRA Au revoir les enfants R L’Auberge espagnole (CC) NRA The aura (SDH) NRA Autumn sonata (2v) NRA Aviva my love R The Baader Meinhof complex (2v) G Babette’s feast (CC) NRA Bad luck NRA Bal NRA Ballad of a soldier (CC) NRA Balzac and the little Chinese seamstress PG-13 The band’s visit (CC) PG-13 Barbara R The Barbarian invasions (CC) NRA Le beau Serge NRA Beaufort NRA The beauty of the devil PG-13 Behind the sun (CC) NRA Belle de Jour FOREIGN DVDs – as of July 2014 NRA Belle Toujours (CC) NRA The best of global lens: Brazil (4v) R The best of youth (2v) (SDH) NRA Beyond the clouds (CC) NRA The bicycle thief R Big girls don’t cry (CC) NRA The big picture (SDH) R Biutiful (CC) PG Black and white in color R Black book NRA Black Orpheus (2v) NRA Blame it on Fidel! NRA Bliss R Blue (CC) NRA The -

Ancient Roma Songs Mek Me Jekhvar Kamav Kaj Zdravo Te Avav, Kaj Me Pro La Dvori Smutna Te Giľava, Kaj Man Mri Daj, Mro Dad Odoj Te Šunena

Jana BELIŠOVÁ Ancient Roma Songs Mek me jekhvar kamav kaj zdravo te avav, kaj me pro la dvori smutna te giľava, kaj man mri daj, mro dad odoj te šunena. Imar na bijina, chodz te bi merava. Phurikane giľa ancient Romany songs © Žudro Project was supported / O projektos šigitinde Next Page Foundation Open Society Foundation First edition 2005 / Jekhto avri diňipen All rights reserved / Savore resipena hine avri thode Editor / E editorka: © Jana Belišová © Jana Belišová, Zuzana Mojžišová Romany parts of book / Romane kotora andre genďi Translation / Thoviben andre aver čhib: František Godla Proofs of translation / Čhibakri korektura andro čhibakro thoviben: František Godla Proof of songs / Čhibakri korektura pal o giľutne lava: Milan Godla, Daniela Šilanová English parts of book / Angličaňika kotora andre genďi Translation / Thoviben andre aver čhib: Mária Nováková, Marián Gazdík Translation of songs / The thovel andre čhib le giľengre lava: Daniela Olejárová Proofs / Čhibakri korektura: Gail Ollsson Photos / O fotografiji: © Daniela Rusnoková, Jana Belišová Ilustrations / O ilustraciji: © Jaroslav Beliš Design / O disajnos: © Zuzana Číčelová, Calder – design community ISBN: 80-968855-5-3 Ancient Romany songs Hoj de pro cintiris bari brana, hoj de na ľigenen mri piraňa. Jaj, de ma ľigen la mek Romale, hoj de na sik avľom, na dikhľom, sovav. Jana BELIŠOVÁ Ancient Romany songs Marián VARGA lavutaris the sthovel o bašaviben Pal oda sar šilales ile lesk ro koncertos andro Manchester, the pal o dujto čho-neskro bašaviben andro Berlin, pro agor apriľiske andro 1904 berš visaľiľas o Bela Bartok pale khere Budapeštate. Leskri voďi sas nasvaľi olestar savi reakcija leske kerde o Angličana, vaš oda geľas andre gemeriko regionos kaj dživelas 5 čhona u odoj pes jekhtovar andro peskro dživipen arakhľas varesoha, so leskro forutuno intelektualno thoviben našťi diňas, oda sas autenticko folkloris. -

The Politics of Roma Expulsions in France and the European Union By

The Politics of Roma Expulsions in France and the European Union By Andrew J. Smith Honors Essay The Department of Romance Languages & Literatures University of North Carolina April 25, 2014 Approved: _____________________ In October 2013, French police intercept a local school bus en route to a field trip and make a rare, public arrest. The incident was out of the ordinary as French government circulaires - leaked government documents - prohibit publicly arresting children and the commonly held French belief maintains that public arrest, and other “perp walks”, are degrading to the accused (Valls 1) (Varela & Gauthier-Villars 1). The target of this highly unusual public arrest was fifteen-year-old Leonarda Dibrani, a Roma girl of Kosovar extraction whose family’s asylum application had been rejected. Dibrani recounts, “All my friends and my teacher were crying, some of them asked me if I had killed someone or stolen something as the police were looking for me. When the police reached the bus they told me to get out and that I had to go back to Kosovo” (“Protests”). Her arrest in front of her schoolmates ignited a subsequent outrage in France and worldwide, with thousands of Parisian high school students protesting and barricading entrances, in one instance, under the banner, “Education in danger” (“Protests”). The Dibrani case, however, is just one of the more publicized episodes in a series of actions taken against France’s foreign Roma population. The goal of these actions has been mass deportation and expulsion of the foreign Roma on the grounds that they reside in France illegally, despite the majority of the foreign Roma being European Union (EU) citizens with a right to move and live across the EU freely. -

Porrajmos. Constructing Gypsy Holocaust Memory in the Recent Cinema

Iwona Sowińska Institute of Culture, Faculty of Management and Social Communication of the Jagiellonian University Porrajmos. Constructing Gypsy Holocaust Memory in the Recent Cinema And perhaps it is so that my memory chooses what it wants for itself? And perhaps it is even better like this because if Gypsies possessed the whole memory, they would die of grief.1 Papusza Abstract: Since the 1990s, the number of films devoted to Roma issues has been increasing at an unprecedented pace. Among them, films on the extermination of the Gypsy during the Second World War can be distinguished.2 Porrajmos in the Romani language means: Romani Holocaust. These events were entirely absent from the public discourse for several decades following the end of the war. The key role in addressing the subject was played by the explosion of memory about the Jewish Holocaust observable since the 1960s. Porrajmos films are in all respects secondary to the representation of the Holocaust - they emerged later, use the same set of conven tions of representation, and their authors are often the artists who emphasize their belonging to the “community of memory” of the Holocaust: once Jewish victims, nowadays their descendants. The Holocaust discourse has thus begun to fulfill the role of “a dominant culture” which allows the story of the Gypsy genocide, providing it is its subordinate version. The passage of time paradoxically strengthens the memory of these events, gen erating an ever-growing number of new places, practices and other texts of remem brance. Nowadays the origin of excavating the Gypsy Holocaust from oblivion is the imminent threat of aggression experienced by members of this ethnic group.