UK Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Tests Factsheet 5: UK Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

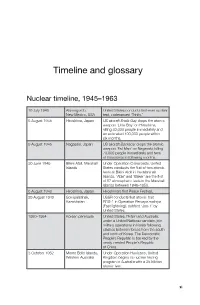

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

MARINEMARINE Life the ‘Taking Over the World’ Edition

MARINEMARINE Life The ‘taking over the world’ edition October/November 2012 ISSUE 21 Our Goal To educate, inform, have fun and share our enjoyment of the marine world with like- minded people. FeaturesFeatures andand CreaturesCreatures The Editorial Staff (and the zen bits, grasshopper) Emma Flukes, Co-Editor: Shallow understanding News from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. BREAKING: Super Trawler stopped – a summary of events & YOUR FEEDBACK 1 [I’m definitely not zen enough to understand any National & International Roundup 6 of this, but let’s run with it anyway...] State-by-state: QLD 8 Michael Jacques, Co-Editor: In the practice of WA 10 tolerance, one's enemy is the best teacher. NT 12 NT Honcho – Grant Treloar TAS 13 Tas Honchos - Phil White and Geoff Rollins SA Honcho – Peter Day WA Honcho – Mike Lee Bits & Pieces Federal marine parks cop a roasting 16 Climate change sceptics on the decline – are we finally getting through? 17 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication The imminent future of Wave Energy 18 are not necessarily the views of the editorial staff or Seaweed: the McDonald’s of the Ocean? 20 associates of this publication. We make no promise that any of this will make sense. Ugly animals need loving too! – an experiment in anthropomorphism 21 Feature Stories Cover Photo; Maori Octopus – John Smith Saving the sand of SA beaches (and more about those cuttlefish…) 24 We are now part of the wonderful The Montebello Islands (WA) - A nuclear wilderness 27 world of Facebook! Check us out, stalk our updates, and ‘like’ our Heritage and Coastal Features page to fuel our insatiable egos. -

We Envy No Man on Earth Because We Fly. the Australian Fleet Air

We Envy No Man On Earth Because We Fly. The Australian Fleet Air Arm: A Comparative Operational Study. This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Murdoch University 2016 Sharron Lee Spargo BA (Hons) Murdoch University I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………………………………………………….. Abstract This thesis examines a small component of the Australian Navy, the Fleet Air Arm. Naval aviators have been contributing to Australian military history since 1914 but they remain relatively unheard of in the wider community and in some instances, in Australian military circles. Aviation within the maritime environment was, and remains, a versatile weapon in any modern navy but the struggle to initiate an aviation branch within the Royal Australian Navy was a protracted one. Finally coming into existence in 1947, the Australian Fleet Air Arm operated from the largest of all naval vessels in the post battle ship era; aircraft carriers. HMAS Albatross, Sydney, Vengeance and Melbourne carried, operated and fully maintained various fixed-wing aircraft and the naval personnel needed for operational deployments until 1982. These deployments included contributions to national and multinational combat, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. With the Australian government’s decision not to replace the last of the aging aircraft carriers, HMAS Melbourne, in 1982, the survival of the Australian Fleet Air Arm, and its highly trained personnel, was in grave doubt. This was a major turning point for Australian Naval Aviation; these versatile flyers and the maintenance and technical crews who supported them retrained on rotary aircraft, or helicopters, and adapted to flight operations utilising small compact ships. -

Australian Radiation Laboratory R

AR.L-t*--*«. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. HOUSING & COMMUNITY SERVICES Public Health Impact of Fallout from British Nuclear Weapons Tests in Australia, 1952-1957 by Keith N. Wise and John R. Moroney Australian Radiation Laboratory r. t J: i AUSTRALIAN RADIATION LABORATORY i - PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF FALLOUT FROM BRITISH NUCLEAR WEAPONS TESTS IN AUSTRALIA, 1952-1957 by Keith N Wise and John R Moroney ARL/TR105 • LOWER PLENTY ROAD •1400 YALLAMBIE VIC 3085 MAY 1992 TELEPHONE: 433 2211 FAX (03) 432 1835 % FOREWORD This work was presented to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia in 1985, but it was not otherwise reported. The impetus for now making it available to a wider audience came from the recent experience of one of us (KNW)* in surveying current research into modelling the transport of radionuclides in the environment; from this it became evident that the methods we used in 1985 remain the best available for such a problem. The present report is identical to the submission we made to the Royal Commission in 1985. Developments in the meantime do not call for change to the derivation of the radiation doses to the population from the nuclear tests, which is the substance of the report. However the recent upward revision of the risk coefficient for cancer mortality to 0.05 Sv"1 does require a change to the assessment we made of the doses in terms of detriment tc health. In 1985 we used a risk coefficient of 0.01, so that the estimates of cancer mortality given at pages iv & 60, and in Table 7.1, need to be multiplied by five. -

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Introduction From the beginning of the nuclear age, the United States, Britain and France sought distant locations to conduct their Cold War programs of nuclear weapons testing. For 50 years between 1946 and 1996, the islands of the central and south Pacific and the deserts of Australia were used as a ‘nuclear playground’ to conduct more than 315 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests, at 10 different sites.1 These desert and ocean sites were chosen because they seemed to be vast, empty spaces. But they weren’t empty. The Western nuclear powers showed little concern for the health and wellbeing of nearby indigenous communities and the civilian and military personnel who staffed the test sites. In the late 1950s, nearly 14,000 British military personnel and scientific staff travelled to the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC) in the central Pacific to support the United Kingdom’s hydrogen bomb testing program. In this military deployment, codenamed Operation Grapple, the British personnel were joined by hundreds of NZ sailors, Gilbertese labourers and Fijian troops.2 Many witnessed the nine atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at Malden Island and Christmas (Kiritimati) Island between May 1957 and September 1958. Today, these islands are part of the independent nation of Kiribati.3 1 Stewart Firth: Nuclear Playground (Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987). 2 Between May 1956 and the end of testing in September 1958, 3,908 Royal Navy (RN) sailors, 4,032 British army soldiers and 5,490 Royal Air Force (RAF) aircrew were deployed to Christmas Island, together with 520 scientific and technical staff from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE)—a total of 13,980 personnel. -

Good News for British Nuclear Test Veterans in Parliament

CAMPAIGN AUTUMN 2020 TM Good news for British nuclear test veterans in Parliament BNTVA Memorials uncovered Media coverage of Britain’s nuclear test veterans IN REMEMBRANCE OF THOSE WHO DID NOT MAKE IT THIS FAR AND IN SUPPORT OF THOSE WHO HAVE Contents Page 1 Page 15 Page 27 A Message from our Patron BNTVA Memorial Puzzle Page from Sir John Hayes CBE MP Leeds Page 28 Page 2 Page 16 Ways to pay your annual BNTVA A Message from the Chair BNTVA Memorials membership subscription from Ceri McDade. Leicester & Liverpool Page 30 Page 4 Page 18 Contact page Why Remember? BNTVA Memorials from the Very Rev. Nicholas Manchester & Paisley Frayling KStJ. BNTVA Chaplain. TRUSTEES Page 19 Ceri McDade BNTVA Memorial Page 5 Chair Portsmouth A Message from John Lax the Revd. Sian Gasson Page 20 Secretary A nuclear test descendant and BNTVA Memorials Ron Watson Vicar of St Gabriel & St Cleopas, Risca & Spalding Treasurer Liverpool. Wesley Perriman Page 21 Curator & Editor Page 6 BNTVA Memorials John McDade Optimism for the British West Ham & The Don Bar Governance Officer Nuclear Test Veterans with the Shelly Grigg Overseas Operations' Bill Page 22 Fallout & Shop Manager A report from Ceri McDade Reader’s Story A meeting with the Kiribati Andi Jones Page 8 Ambassador regarding Montebello Representative National Atomic Veterans Nuclear Testing by John Lax David Bostwick Awareness Day and Ron Watson Trustee A report from Wesley Perriman Page 24 Page 9 Guinea Pig Ship BNTVA Memorial A book written National Memorial Arboretum, by Brian Marshall We want to hear Alrewas, Staffordshire Page 24 from you.. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Management Proposals for and Surrounding Waters

ManagementProposals for the Montebellolslands and SurroundingWaters CALMOccosionol Poper No. 3/91 AUCUST1991 Department of Conservationand Land Management Como, WesternAustratia srlsrFnv uasaia outoc puetauull purl pul uorts JoeuooJo auudeq e$ Iq paqqlqnd 1661pniny .oN.radu6 16l€ puolsocco I^nyC s909..v.ll .oo$uu8a I9 rof, 'o'al a4EC rlcr8eseueJIlpIl& peuaErurry purl pur uoF8l.rasmCJo lueqldeq slrroy[ 'q'x srelul\ tupuno.r.rng puc spuBIsIo11aqeluol I eql roJ qusodor4 1uerueEuuu141 oDepartmentof Conservationand Land Management,Western Australia 1991 rssN103l-4865 Mariannelrwis... SeriesEditor RaeleneHick and Jan R"yo* . Page preparation CALM Land Information Branch . , . Illustrations CALM Corporaie Relations . Production and distribution |lr .IJV 'i$uoqlny 1itnv3 eW raprm perederdeq 111,nueld lueueSsuutu u uop? Jesuoc eJnlsN prrP s{JBd IsuopEN er0 q FalseA ueaq seq prru 'Io.quoc s,erl?r1snvuelsed\ repun up8e sI eale eql ecu6| 'lueluuJe^o9 elels eql ol gJurnpJ sI loJluoc uaq.n luerueSeueurdrolcu;spus e Bq IILI SprrElsreql lsrll BIIe4snv lueNed\ uo{ eJuelnsss ue se spsodord ;o lueurelqs qq1 se4nber rnpe^\uoruruo3 eqJ '9S6I puu ZS6I uI erelp slsegsuodee,n realcnu 'ZS6I rtsplrg eql 3ur.ino11og lcv (s8uqruepun plreds) ecueJeq erp repun uere petlqlqord e 3u1eq i(q qtpe,nuouuroC eql Jo Ioruoc erp reprm fpuermc are sJg1eASqpunorrns pus spuEIsIeqJ 'spIcUJo t{llPel\uouuoC pu? elqs IIIEAoIaJuee/$Fq uossllnsuoc tuo4 Suupser 'sr4z,n Sulpunorrns pIIB splrulsl oileq4uol I eql roy spsodord s,elp4sny uatsei . Jo lueulelqs 't86I ? q tI lcv I ITVC erp repun ueld luauaSeueru? lou q sIqL accJiud .I z'''''' spuslslolleq4uol l ergJo uonB.o-I sgun9ld """ 8""" G86I) BJlsqsnvuI stsetrrDepnN qsFgfl €rll otul u)rssruuoC p,(oX eq1;o godaa aql uo.l; Eoertxq XIqNlIdiIV L'" "', sgcNsuaJnu 9" " .' ' ' ' ' rNaI{ggvNvl/tuod qgunoau sacuoosgu " " .. -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan Page 1 of 3 Book Review: Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan In Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests, Nic Maclellan gathers together oral history and archival materials to bring forth a more democratic history of the British hydrogen bomb test series Operation Grapple, conducted in the South Pacific between 1957-58. Centralising the experiences and voices of Pacific islanders still affected by the detonations and still fighting for recognition and recompense from the UK government, this book — available to download here for free — offers a textured, multi-layered story that gives urgent attention to historical legacies of nuclear harm and injustice, writes Tom Vaughan. Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests. Nic Maclellan. ANU Press. 2017. Find this book: Sixty years after the British hydrogen bomb test series Operation Grapple was conducted in the South Pacific, its remaining survivors — now octogenarians — continue to fight for recognition and recompense from the UK government. The Grapple series, running from May 1957 to September 1958, consisted of nine nuclear detonations across test sites on Malden and Christmas (Kiritimati) Islands and announced the UK’s arrival as the world’s third thermonuclear power. As a shrinking Empire trickled through Britannia’s fingers, Grapple briefly salved the rapidly developing British condition of postcolonial melancholia by anointing the UK with destructive capabilities disproportionate to its diminishing influence, and helping to secure British ‘seats at the table’ in global affairs for decades to come. -

Thesis Front 2

Nuclear New Zealand: New Zealandʼs nuclear and radiation history to 1987 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History and Philosophy of Science in the University of Canterbury by Rebecca Priestley, BSc (hons) University of Canterbury August 2010 Table of contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Chapter 1 Nuclear-free New Zealand: Reality or a myth to be debunked? 3 Chapter 2 The radiation age: Rutherford, New Zealand and the new physics 25 Chapter 3 The public are mad on radium! Applications of the new science 45 Chapter 4 Some fool in a laboratory: The atom bomb and the dawn of the nuclear age 80 Chapter 5 Cold War and red hot science: The nuclear age comes to the Pacific 110 Chapter 6 Uranium fever! Uranium prospecting on the West Coast 146 Chapter 7 Thereʼs strontium-90 in my milk: Safety and public exposure to radiation 171 Chapter 8 Atoms for Peace: Nuclear science in New Zealand in the atomic age 200 Chapter 9 Nuclear decision: Plans for nuclear power 231 Chapter 10 Nuclear-free New Zealand: The forging of a new national identity 257 Chapter 11 A nuclear-free New Zealand? The ideal and the reality 292 Bibliography 298 1 Abstract New Zealand has a paradoxical relationship with nuclear science. We are as proud of Ernest Rutherford, known as the father of nuclear science, as of our nuclear-free status. Early enthusiasm for radium and X-rays in the first half of the twentieth century and euphoria in the 1950s about the discovery of uranium in a West Coast road cutting was countered by outrage at French nuclear testing in the Pacific and protests against visits from American nuclear-powered warships.