Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

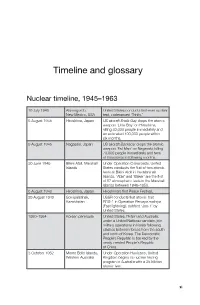

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

2002 11.2Minpro.Pdf

66 Printed 23.10.02 NORFOLK ISLAND TENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS WEDNESDAY 16 OCTOBER 2002 NORF’K AILEN DIISEM MENETS LARNEN WATHING HAEPN INAA TENTH LEJESLIETEW ‘SEMBLE WENSDI 16 OKTOEBA 2002 1 The Legislative Assembly met at 10.05 am. The Speaker (Hon D.E. Buffett) took the Chair and read the Prayer 2 CONDOLENCES Ms Nicholas recorded the passing of – Lillian May Ruth Barrett As a mark of respect to the memory of the deceased all Members stood in silence 2A WELCOME TO PUBLIC GALLERY The Speaker welcomed to the Public Gallery Mr Kilgariff, a former Speaker of the Northern Territory Parliament, and a former Australian Senator 3 QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE Deputy Speaker Nicholas took the Chair at 10.36 am Time for questions without notice have expired Mr Nobbs moved – THAT time for questions without notice be extended by 15 minutes Question put and agreed to on the voices, Mr Brown being absent from the Chamber 4 ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS ON NOTICE Answers were provided to the following questions on notice: No. 35 (Mr Brown to Minister for Finance) re. Administration policy in relation to damage to Administration vehicles when privately used No. 36 (Mr Brown to Chief Minister) re. Temporary Entry permits issued to Administration staff No. 37 (Mr Brown to Minister for Finance) re. Purchase of multi tyred road roller by the Administration 5 PRESENTATION OF PAPERS The following Papers were presented to the House: (1) Mr D. Buffett (Minister for Community Services and Tourism) – Tourist Accommodation Amendment (Safety Compliance) Regulations 2002 67 (2) Mr Donaldson (Minister for Finance) – a) tabled detail of directions given by executive member for virement of funds during period 20 September 2002 and 9 October 2002; Mrs Jack moved – THAT the House take note of the Paper Debate ensued Question put and agreed to on the voices b) Public Sector Remuneration Tribunal Act 1992 – Determination by the Tribunal in respect of Application No. -

Brisbane Grammar School Magasine

Vol. XV. APRIL, 1918. No. 45. BRI S HANEN Ej GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZIN E. 9.I 4 ritbanr : i: OI-TKI;I.;- I'RIN'ING CO., LTD.-98 Ul'K*'-N 8TREKT 1913. |i III I . ,II, I I I TheSel-tilling Outridge 5/- A Genuine I Fountain Pen. Time Save I__ Simle yrtagel Actieon, Actual alegth It inches. 14ct. Gold Nib. Masutactured Ipecially for Outridge Printing Co. Ltd. SPECIAL OFFER t IPrea Trial and Guarastee. 9le Sket Time O ly. This Pen will be lent you P etagel Paid on receipt of Postal Note for 5f- (Stamps winl be accepted if more convlient). You will be Pleased with the pen but we guarantee to send your Mosey back If you are not ktidiedt , rovided you return it within 7 days. ow to r -Just cut out this order, sign it, sad y r rees, sad send it to us with postal order. The Pen will be in your hands by the next mail; but you must Orier Neow as this offer will only lst a few days. Outridge Printing Com pany Ltd @S9 Qqe 8teeIt. ',Iebae.. U - Brisbane Grammar School Magasine. 8 Sehool Institutions. School Committee. SPORTS' MASTER ... ... ... MR. S. STEPHENSON HON. TREASURER ...... ... MR. R. E. HIIWAITES CRICKET CAPTAIN ... ... ... M. D. GRAHAM COMMITTEE ... Mi. W. R. IOWMAN, A. F. PA'TON, R C. TROUT, G. C. C. WII.so DEI.EGATE TO Q.L.T.A. ... ... MR. H. PORTEnR OTHER CAPTAINS 2nd W1RENCH ; 3rd BARN:S, C. G ; 4 th FRASER, K. B.; 5 th BRADFIEI.D, C. A.; 6th KIl ROE Librarians.-N. -

The Life and Times of the Remarkable Alf Pollard

1 FROM FARMBOY TO SUPERSTAR: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REMARKABLE ALF POLLARD John S. Croucher B.A. (Hons) (Macq) MSc PhD (Minn) PhD (Macq) PhD (Hon) (DWU) FRSA FAustMS A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology, Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2014 2 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 12 August 2014 3 INTRODUCTION Alf Pollard’s contribution to the business history of Australia is as yet unwritten—both as a biography of the man himself, but also his singular, albeit often quiet, achievements. He helped to shape the business world in which he operated and, in parallel, made outstanding contributions to Australian society. Cultural deprivation theory tells us that people who are working class have themselves to blame for the failure of their children in education1 and Alf was certainly from a low socio-economic, indeed extremely poor, family. He fitted such a child to the letter, although he later turned out to be an outstanding counter-example despite having no ‘built-in’ advantage as he not been socialised in a dominant wealthy culture. -

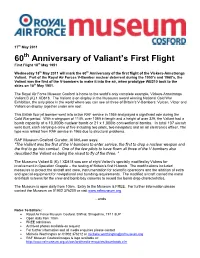

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

Community Directory Volume I 2003 - 2016

Standards Community Directory Volume I 2003 - 2016 The Standards Review Program has been developed by Museums & Galleries of NSW and Museums & Galleries Queensland and funded by Arts NSW and Arts Queensland. 2 Welcome to the Standards Community 2017 What is the Standards Review How do I use the Standards Program? Community Directory? This program, implemented by Museums & Galleries of NSW The Standards Community Directory features a profile of each (M&G NSW) in 2003, and since 2005 in partnership with museum and gallery that has gone through the Standards Review Museums & Galleries Queensland (M&G QLD), supports Program. The profile includes a description of each organisation, museums and galleries through a process of self-review and contact details and how they benefitted from participating in the external feedback. Standards Review Program. It provides an exciting opportunity for museums and galleries Each organisation listed in this directory: to assess their practices and policies against the National • Is promoting its unique profile to the “Standards Community” Standards for Australian Museums and Galleries. The program and wider audiences aims to establish a long term network for sustainable community • Is available to assist and answer any questions you may museums and galleries as well as acknowledging the hard work have as you undertake each stage of the Standards Review undertaken by volunteers and paid staff to maintain Australian Program heritage. • Is contactable via the details and hours as per their profile page What are the key components? • Will share with all other “Standards Community” members (including new members) their achievements and outcomes • Working with regional service providers to develop ongoing from participating in the Standards Review Program support for museums and galleries • Has provided words of support and encouragement to new • Self-assessment by participants guided by the National participants in the Standards Review Program. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17

Contents Part 1: Foreword Susan Denyer 3 Part 2: Context for the Thematic Study Anita Smith 5 - Purpose of the thematic study 5 - Background to the thematic study 6 - ICOMOS 2005 “Filling the Gaps - An Action Plan for the Future” 10 - Pacific Island Cultural Landscapes: making use of this study 13 Part 3: Thematic Essay: The Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17 The Pacific Islands: a Geo-Cultural Region 17 - The environments and sub-regions of the Pacific 18 - Colonization of the Pacific Islands and the development of Pacific Island societies 22 - European contact, the colonial era and decolonisation 25 - The “transported landscapes” of the Pacific 28 - Principle factors contributing to the diversity of cultural Landscapes in the Pacific Islands 30 Organically Evolved Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific 31 - Pacific systems of horticulture – continuing cultural landscapes 32 - Change through time in horticultural systems - relict horticultural and agricultural cultural landscapes 37 - Arboriculture in the Pacific Islands 40 - Land tenure and settlement patterns 40 - Social systems and village structures 45 - Social, ceremonial and burial places 47 - Relict landscapes of war in the Pacific Islands 51 - Organically evolved cultural landscapes in the Pacific Islands: in conclusion 54 Cultural Landscapes of the Colonial Era 54 Associative Cultural Landscapes and Seascapes 57 - Storied landscapes and seascapes 58 - Traditional knowledge: associations with the land and sea 60 1 Part 4: Cultural Landscape Portfolio Kevin L. Jones 63 Part 5: The Way Forward Susan Denyer, Kevin L. Jones and Anita Smith 117 - Findings of the study 117 - Protection, conservation and management 119 - Recording and documentation 121 - Recommendations for future work 121 Annexes Annex I - References 123 Annex II - Illustrations 131 2 PART 1: Foreword Cultural landscapes have the capacity to be read as living records of the way societies have interacted with their environment over time. -

Social and Economic Environment: GCCC Soer 1997

Chapter 9: Social and Economic Environment: GCCC SoER 1997 Chapter 9: Social and economic environment 9.1 Summary and Indicators 9.1.1 Summary The Gold Coast has been described as a classic sunbelt city that, in addition to tourism, has an economy based on settlement by retirees. Both of these groups come to the Gold Coast to enjoy the climate, the environment and the lifestyle. It has been long established that the environmental issues are given lower standing in times, or locations, of economic or social hardship. Consequently the social and economic basis of the City of Gold Coast, and the attitude of the community toward the environment, is fundamental to the sustainability of the City. Currently some 70% of Australians believe the environment to be at least as important as the economy. State The per capita gross regional product of the City, while significant, appears to be only around half of that of the State, or Australia. This situation is also reflected in the household income for the City which was $29,500 in 1991 and is lower than that for Queensland ($31,815) and Australia ($34,987). Conversely the cost of living on the Gold Coast is similar to that for the rest of Southeast Queensland (SEQ) and the cost of accommodation is higher than for the rest of SEQ. Most of the energy used on the Gold Coast is derived from external sources; there are few alternative renewable sources of energy used. This is despite the potential to use solar, wind and tidal/wave generators. Based on the gross regional product estimates, the Gold Coast consumes twice as much energy for every dollar produced than Australia as a whole. -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Introduction From the beginning of the nuclear age, the United States, Britain and France sought distant locations to conduct their Cold War programs of nuclear weapons testing. For 50 years between 1946 and 1996, the islands of the central and south Pacific and the deserts of Australia were used as a ‘nuclear playground’ to conduct more than 315 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests, at 10 different sites.1 These desert and ocean sites were chosen because they seemed to be vast, empty spaces. But they weren’t empty. The Western nuclear powers showed little concern for the health and wellbeing of nearby indigenous communities and the civilian and military personnel who staffed the test sites. In the late 1950s, nearly 14,000 British military personnel and scientific staff travelled to the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC) in the central Pacific to support the United Kingdom’s hydrogen bomb testing program. In this military deployment, codenamed Operation Grapple, the British personnel were joined by hundreds of NZ sailors, Gilbertese labourers and Fijian troops.2 Many witnessed the nine atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at Malden Island and Christmas (Kiritimati) Island between May 1957 and September 1958. Today, these islands are part of the independent nation of Kiribati.3 1 Stewart Firth: Nuclear Playground (Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987). 2 Between May 1956 and the end of testing in September 1958, 3,908 Royal Navy (RN) sailors, 4,032 British army soldiers and 5,490 Royal Air Force (RAF) aircrew were deployed to Christmas Island, together with 520 scientific and technical staff from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE)—a total of 13,980 personnel.