Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

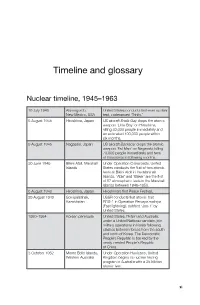

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E

ROUNDTABLE: NONPROLIFERATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E. C. Hymans* uclear weapons proliferation is at the top of the news these days. Most recent reports have focused on the nuclear efforts of Iran and North N Korea, but they also typically warn that those two acute diplomatic headaches may merely be the harbingers of a much darker future. Indeed, foreign policy sages often claim that what worries them most is not the small arsenals that Tehran and Pyongyang could build for themselves, but rather the potential that their reckless behavior could catalyze a process of runaway nuclear proliferation, international disorder, and, ultimately, nuclear war. The United States is right to be vigilant against the threat of nuclear prolifer- ation. But such vigilance can all too easily lend itself to exaggeration and overreac- tion, as the invasion of Iraq painfully demonstrates. In this essay, I critique two intellectual assumptions that have contributed mightily to Washington’s puffed-up perceptions of the proliferation threat. I then spell out the policy impli- cations of a more appropriate analysis of that threat. The first standard assumption undergirding the anticipation of rampant pro- liferation is that states that abstain from nuclear weapons are resisting the dictates of their narrow self-interest—and that while this may be a laudable policy, it is also an unsustainable one. According to this line of thinking, sooner or later some external shock, such as an Iranian dash for the bomb, can be expected to jolt many states out of their nuclear self-restraint. -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

The Fallacy of Nuclear Deterrence

THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet JCSP 41 PCEMI 41 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2015. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2015. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 41 – PCEMI 41 2014 – 2015 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

Science, Technology and Medicine In

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/9781139044301.012 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Edgerton, D., & Pickstone, J. V. (2020). The United Kingdom. In H. R. Slotten, R. L. Numbers, & D. N. Livingstone (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Science: Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context (Vol. 8, pp. 151-191). (Cambridge History of Science; Vol. 8). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139044301.012 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17

Contents Part 1: Foreword Susan Denyer 3 Part 2: Context for the Thematic Study Anita Smith 5 - Purpose of the thematic study 5 - Background to the thematic study 6 - ICOMOS 2005 “Filling the Gaps - An Action Plan for the Future” 10 - Pacific Island Cultural Landscapes: making use of this study 13 Part 3: Thematic Essay: The Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17 The Pacific Islands: a Geo-Cultural Region 17 - The environments and sub-regions of the Pacific 18 - Colonization of the Pacific Islands and the development of Pacific Island societies 22 - European contact, the colonial era and decolonisation 25 - The “transported landscapes” of the Pacific 28 - Principle factors contributing to the diversity of cultural Landscapes in the Pacific Islands 30 Organically Evolved Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific 31 - Pacific systems of horticulture – continuing cultural landscapes 32 - Change through time in horticultural systems - relict horticultural and agricultural cultural landscapes 37 - Arboriculture in the Pacific Islands 40 - Land tenure and settlement patterns 40 - Social systems and village structures 45 - Social, ceremonial and burial places 47 - Relict landscapes of war in the Pacific Islands 51 - Organically evolved cultural landscapes in the Pacific Islands: in conclusion 54 Cultural Landscapes of the Colonial Era 54 Associative Cultural Landscapes and Seascapes 57 - Storied landscapes and seascapes 58 - Traditional knowledge: associations with the land and sea 60 1 Part 4: Cultural Landscape Portfolio Kevin L. Jones 63 Part 5: The Way Forward Susan Denyer, Kevin L. Jones and Anita Smith 117 - Findings of the study 117 - Protection, conservation and management 119 - Recording and documentation 121 - Recommendations for future work 121 Annexes Annex I - References 123 Annex II - Illustrations 131 2 PART 1: Foreword Cultural landscapes have the capacity to be read as living records of the way societies have interacted with their environment over time. -

Malden Island, Kiribati – Feasibility of Cat Eradication for the Recovery of Seabirds

MALDEN ISLAND, KIRIBATI – FEASIBILITY OF CAT ERADICATION FOR THE RECOVERY OF SEABIRDS By Ray Pierce, Derek Brown, Aataieta Ioane and Kautabuki Kamatie December 2015 Frontispiece - Grey backed Terns at a colony in Sesuvium and Portulaca near the main Malden lagoon. 1 CONTENTS MAP OF KIRIBATI 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 ACRONYMS AND KEY DEFIMITIONS 4 MAP OF MALDEN 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF MALDEN ISLAND 5 2.1 Geology and landforms 5 2.2 Climate and weather 6 2.3 Human use 6 2.4 Vegetation and flora 7 3 FAUNA 10 3.1 Breeding seabirds 10 3.2 Visiting seabirds 13 3.3 Shorebirds 13 3.4 Other indigenous fauna 14 4. INVASIVE SPECIES AND THEIR IMPACTS 15 4.1 Past invasives 15 4.2 House mouse 16 4.3 Feral house cat 17 5 ERADICATION BENEFITS, RISKS, COSTS AND FEASIBILITY 20 5.1 Benefits of cat eradication 20 5.2 Benefits of mouse eradication 20 5.3 Eradication Feasibility 21 5.4 Risks 24 5.5 Estimated Costs 25 6. Preliminary Recommendations 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 28 REFERENCES 28 APPENDICES – Flora species, Seabird status, Fly-ons, Pelagic counts 32 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study describes the biodiversity values of Malden Island, Kiribati, and assesses the potential benefits, feasibility and costs of removing key invasive species. Malden is relatively pest-free, but two significant invasive species are present - feral house cats and house mice. We believe that the most cost-effective and beneficial conservation action in the short term for Kiribati is to undertake a cat eradication programme. This would take pressure off nearly all of the 11 species of seabirds which currently breed at Malden, and allow for the natural and/or enhanced recovery of a further 5-6 species, including the Phoenix Petrel (EN). -

Kiribati (A.K.A. Gilbertese) Helps for Reading Vital Records

Kiribati (a.k.a. Gilbertese) Helps for Reading Vital Records Alan Marchant, 29 January 2021 Alphabet • Kiribati uses only the following letters. All other letters are rare before the late 20th century, except in foreign names. A B E I K M N NG O R T U W • The letter T is very common, especially at the beginning of names. The uppercase cursive T can sometimes be confused with the unlikely P or S. Lower-case t is often written with the cross-bar shifted right, detached from the vertical stroke. • Lower-case g is the only letter with a down-stroke. It exists only in the combination ng (equivalent to ñ). • The cursive lower-case n and u are about equally common and are not easily distinguished; lower-case n and r are more distinguishable. Months English and Kiribati forms may exist in the same document. January Tianuari July Turai February Beberuare August Aokati March Mati September Tebetembwa April Eberi October Okitobwa May Mei November Nobembwa June Tun December Ritembwa Terminology Kiribati words can have many alternate meanings. This list identifies usages encountered in the headings of vital records. aba makoro island ma and abana resident maiu life aika of, who makuri occupation aine female mane, mwane male akea none (n.b. not mare married a name) aki not mate dead ana her, his matena death ao and, with mwenga home araia list na. item number aran name namwakina month are that natin children atei children nei, ne, N female title auti home ngkana, ñkana when boki book ni of bongina date o n aoraki hospital buki cause raure divorced bun, buna spouse ririki year, age bung birth tabo place buniaki born tai date e he, she taman father iai was, did te article (a, an, the) iein married tei child I-Kiribati native islander ten, te, T male title I-Matang foreigner tenua three karerei authorization teuana one karo parent tinan mother kawa town tuai not yet ke or ua, uoua two korobokian register Names • Strings of vowels (3 or more) are common.