Malden Island, Kiribati – Feasibility of Cat Eradication for the Recovery of Seabirds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

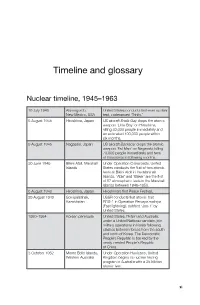

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group

Final Report for the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development Compile and Review Invasive Alien Species Information Shyama Pagad Programme Officer, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group 1 Table of Contents Glossary and Definitions ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 1 ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Alien and Invasive Species in Kiribati .............................................................................................. 7 Key Information Sources ................................................................................................................. 7 Results of information review ......................................................................................................... 8 SECTION 2 ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Pathways of introduction and spread of invasive alien species ................................................... 10 SECTION 3 ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Kiribati and its biodiversity .......................................................................................................... -

Preliminary Synopsis of Oral History Interviews at Rawaki Village And

Preliminary Synopsis of Oral History Interviews at Rawaki Village and Nikumaroro Village Solomon Islands by The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) November 26, 2011 Nikumaroro Village Preliminary Synopsis of Oral History Interviews, Solomon Islands 2011 From August 20-30, 2011, John Clauss, Nancy Farrell, Karl Kern, Baoro Laxton Koraua and Gary F. Quigg, of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR) conducted a research expedition in the Solomon Islands consisting of oral history interviews with former residents of Nikumaroro Island (Kiribati) as well as a thorough examination of relevant archival materials in the Solomon Islands National Archives. This preliminary synopsis provides an initial overview of the research conducted by TIGHAR as a part of further testing the Earhart Project’s Nikumaroro Hypothesis. A more detailed report will follow, when the audio and video recordings have been completely transcribed and analyzed. Procedures Upon arrival in Honiara (Guadalcanal), Clauss, Farrell, Kern and Quigg were met by Koraua at the airport. Mr. Koraua is a resident of Honiara and the son of Paul Laxton. Mr. Laxton, who served as Assistant Lands Commissioner for the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, was the British Colonial Service officer in charge of the settlement on Gardner Island (Nikumaroro Island) for several years following World War II. Born on Nikumaroro Island in 1960, Mr. Koraua was relocated to the Solomon Islands along with the entire population of the Nikumaroro Island colony in 1963. Mr. Koraua was crucial to the success of the expedition, acting as interpreter, logistics coordinator, ambassador and gracious host. Further, Mr. Koraua provided for our transportation between the outer islands of Kohinggo and Vaghena aboard his boat, the M/V Temauri. -

Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 97 TABLE 1

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 97 Country Name: Kiribati TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Station (include data period) September 2015 July August Total 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking 2015 2015 Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (mm) Total Total (mm) (mm) Kanton 224 165.8 - 20.1 51.5 40.0 - Kiritimati 417.3 171.7 124.9 4.0 15.4 8.0 81 Tarawa 171.9 233.1 358.5 55.1 142.8 84.3 64 Butaritari 87.8 176.7 178.6 113.3 177.3 136 52 Beru 135.8 - - 28.1 68.0 43.3 - TABLE 2: Three-monthly Rainfall July to September 2015 [Please note that the data used in this verification should be sourced from table 3 of OCOF #93] Station Three-month 33%tile 67%tile Median Ranking Forecast probs.* Verification * Total Rainfall Rainfall Rainfall (include LEPS) (Consistent, (mm) (mm) (mm) Near- consistent Inconsistent? Kanton - 138.2 219.0 170.9 - 17/ 43 /40 (0.7) - Kiritimati 713.9 42.6 101.3 72.1 88/88 26/29/ 45 (-0.1) Consistent Tarawa 763.5 195.8 543.6 335.0 56/66 6/14/ 80 (19.7) Consistent Butaritari 443.1 506.3 743.0 634.0 16/73 5/35/ 60 (13.5) Inconsistent Beru - 130.7 292.5 173.5 - 3/13/ 84 (23.8) - Period:* below normal /normal /above normal Predictors and Period used for July to September 2015 Outlooks (refer to OCOF #93): Nino 3.4 SST Anomalies extended (2mths) * Forecast is consistent when observed and predicted (tercile with the highest probability) categories coincide (are in the same tercile). -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

Participatory Diagnosis of Coastal Fisheries for North Tarawa And

Photo credit: Front cover, Aurélie Delisle/ANCORS Aurélie cover, Front credit: Photo Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Authors Aurélie Delisle, Ben Namakin, Tarateiti Uriam, Brooke Campbell and Quentin Hanich Citation This publication should be cited as: Delisle A, Namakin B, Uriam T, Campbell B and Hanich Q. 2016. Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Report: 2016-24. Acknowledgments We would like to thank the financial contribution of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research through project FIS/2012/074. We would also like to thank the staff from the Secretariat of the Pacific Community and WorldFish for their support. A special thank you goes out to staff of the Kiribati’s Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Land and Agricultural Development and to members of the five pilot Community-Based Fisheries Management (CBFM) communities in Kiribati. 2 Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 Methods 9 Diagnosis 12 Summary and entry points for CBFM 36 Notes 38 References 39 Appendices 42 3 Executive summary In support of the Kiribati National Fisheries Policy 2013–2025, the ACIAR project FIS/2012/074 Improving Community-Based -

The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 7, No.1, 2012, pp. 135-146 REVIEW ESSAY The Partition of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands W. David McIntyre Macmillan Brown Centre for Pacific Studies Christchurch, New Zealand [email protected] ABSTRACT : This paper reviews the separation of the Ellice Islands from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, in the central Pacific, in 1975: one of the few agreed boundary changes that were made during decolonization. Under the name Tuvalu, the Ellice Group became the world’s fourth smallest state and gained independence in 1978. The Gilbert Islands, (including the Phoenix and Line Islands), became the Republic of Kiribati in 1979. A survey of the tortuous creation of the colony is followed by an analysis of the geographic, ethnic, language, religious, economic, and administrative differences between the groups. When, belatedly, the British began creating representative institutions, the largely Polynesian, Protestant, Ellice people realized they were doomed to permanent minority status while combined with the Micronesian, half-Catholic, Gilbertese. To protect their identity they demanded separation, and the British accepted this after a UN-observed referendum. Keywords: Foreign and Commonwealth Office; Gilbert and Ellis islands; independence; Kiribati; Tuvalu © 2012 Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Context The age of imperialism saw most of the world divided up by colonial powers that drew arbitrary lines on maps to designate their properties. The age of decolonization involved the assumption of sovereign independence by these, often artificial, creations. Tuvalu, in the central Pacific, lying roughly half-way between Australia and Hawaii, is a rare exception. -

Kiritimati and Malden, Kiribati, Nuclear Weapons Test Sites

Kiritimati and Malden, Kiribati, Nuclear weapons test sites A total of 33 nuclear detonations were conducted on two atolls of the Republic of Kiribati by the UK and the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s. Thousands of islanders and servicemen were subjected to radioactive fallout and now su er from radiation e ects. History The Pacifi c atoll of Kiritimati (formerly the British colo- ny “Christmas Island”), served during WWII as a stop- over for the U.S. Air Force on its way to Japan. After the war, the United Kingdom used the atolls for its fi rst series of fi ssion bomb explosions. Due to agree- ments made with the Australian government, these servicemen and the indigenous population were free explosions could not be conducted at the British nu- to move around the island, consuming local water and clear testing site at Maralinga. On May 15, 1957, the fruits, bathing in contaminated lagoons and breathing fi rst British hydrogen bomb, code-named “Operation in radioactive dust.1 Grapple,” was exploded off the coast of Malden, fol- In 2006, 300 former Christmas Island residents sub- lowed by another a month later, neither of which yield- mitted a petition to the European Parliament, accus- ed the explosive power that was expected. The tests ing the UK of knowingly exposing them to radioactive reached a maximum yield of 720 kilotons, equivalent fallout despite knowing of the dangers. Declassifi ed to more than 50 times the power of the bomb that was government documents from the time warned that ra- dropped on Hiroshima. -

Geology and Geochronology of the Line Islands

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 89, NO. B13, PAGES 11,261-11,272,DECEMBER 10, 1984 Geology and Geochronologyof the Line Islands S. O. SCHLANGER,1 M. O. GARCIA,B. H. KEATING,J. J. NAUGHTON, W. W. SAGER,2 J. g. HAGGERTY,3 AND J. g. PHILPOTTS4 Hawaii Institute of Geophysics,University of Hawaii, Honolulu R. A. DUNCAN Schoolof Oceano•Iraphy,Ore,ion State University,Corvallis Geologicaland geophysicalstudies along the entire length of the Line Islands were undertakenin order to test the hot spot model for the origin of this major linear island chain. Volcanic rocks were recoveredin 21 dredge hauls and fossiliferoussedimentary rocks were recoveredin 19 dredge hauls. Volcanic rocks from the Line Islands are alkalic basalts and hawaiites. In addition, a tholeiitic basalt and a phonolite have been recoveredfrom the central part of the Line chain. Microprobe analysesof groundmassaugite in the alkalic basaltsindicate that they contain high TiO2 (1.0-4.0 wt %) and A1203 (3.4-9.1 wt %) and are of alkaline to peralkaline affinities.Major element compositionsof the Line Islandsvolcanic rocks are very comparableto Hawaiian volcanicrocks. Trace elementand rare earth elementanalyses also indicatethat the rocksare typical of oceanicisland alkalic lavas' the Line Islands lavas are very much unlike typical mid-oceanridge or fracturezone basalts.Dating of theserocks by '•øAr-39Ar,K-Ar, and paleontologicalmethods, combined with DeepSea Drilling Projectdata from sites 165, 315, and 316 and previouslydated dredgedrocks, provide ages of volcanic eventsat 20 localities along the chain from 18øN to 9øS,a distanceof almost4000 km. All of thesedates define mid-Cretaceous to late Eoceneedifice or ridge-buildingvolcanic events. -

The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography

ISSN 1031-8062 ISBN 0 7305 5592 5 The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography K. A. Rodgers and Carol' Cant.-11 Technical Reports of the Australian Museu~ Number-t TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Technical Reports of the Australian Museum is D.J.G . Griffin a series of occasional papers which publishes Editor: bibliographies, catalogues, surveys, and data bases in J.K. Lowry the fields of anthropology, geology and zoology. The journal is an adjunct to Records of the Australian Assistant Editor: J.E. Hanley Museum and the Supplement series which publish original research in natural history. It is designed for Associate Editors: the quick dissemination of information at a moderate Anthropology: cost. The information is relevant to Australia, the R.J. Lampert South-west Pacific and the Indian Ocean area. Invertebrates: Submitted manuscripts are reviewed by external W.B. Rudman referees. A reasonable number of copies are distributed to scholarly institutions in Australia and Geology: around the world. F.L. Sutherland Submitted manuscripts should be addressed to the Vertebrates: Editor, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney A.E . Greer South, N.S.W. 2000, Australia. Manuscripts should preferably be on 51;4 inch diskettes in DOS format and ©Copyright Australian Museum, 1988 should include an original and two copies. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the Editor. Technical Reports are not available through subscription. New issues will be announced in the Produced by the Australian Museum Records. Orders should be addressed to the Assistant 15 September 1988 Editor (Community Relations), Australian Museum, $16.00 bought at the Australian Museum P.O. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

Plants of Kiribati

KIRIBATI State of the Environment Report 2000-2002 Government of the Republic of Kiribati 2004 PREPARED BY THE ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION DIVISION Ministry of Environment Lands & Agricultural Development Nei Akoako MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMEN P.O. BOX 234 BIKENIBEU, TARAWA KIRIBATI PHONES (686) 28000/28593/28507 Ngkoa, FNgkaiAX: (686 ao) 283 n34/ Taaainako28425 EMAIL: [email protected] GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF KIRIBATI Acknowledgements The report has been collectively developed by staff of the Environment and Conservation Division. Mrs Tererei Abete-Reema was the lead author with Mr Kautoa Tonganibeia contributing to Chapters 11 and 14. Mrs Nenenteiti Teariki-Ruatu contributed to chapters 7 to 9. Mr. Farran Redfern (Chapter 5) and Ms. Reenate Tanua Willie (Chapters 4 and 6) also contributed. Publication of the report has been made possible through the kind financial assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. The front coverpage design was done by Mr. Kautoa Tonganibeia. Editing has been completed by Mr Matt McIntyre, Sustainable Development Adviser and Manager, Sustainable Economic Development Division of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). __________________________________________________________________________________ i Kiribati State of the Environment Report, 2000-2002 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................. I TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................