Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

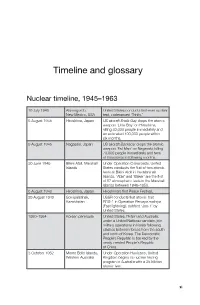

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E

ROUNDTABLE: NONPROLIFERATION IN THE 21ST CENTURY The Threat of Nuclear Proliferation: Perception and Reality Jacques E. C. Hymans* uclear weapons proliferation is at the top of the news these days. Most recent reports have focused on the nuclear efforts of Iran and North N Korea, but they also typically warn that those two acute diplomatic headaches may merely be the harbingers of a much darker future. Indeed, foreign policy sages often claim that what worries them most is not the small arsenals that Tehran and Pyongyang could build for themselves, but rather the potential that their reckless behavior could catalyze a process of runaway nuclear proliferation, international disorder, and, ultimately, nuclear war. The United States is right to be vigilant against the threat of nuclear prolifer- ation. But such vigilance can all too easily lend itself to exaggeration and overreac- tion, as the invasion of Iraq painfully demonstrates. In this essay, I critique two intellectual assumptions that have contributed mightily to Washington’s puffed-up perceptions of the proliferation threat. I then spell out the policy impli- cations of a more appropriate analysis of that threat. The first standard assumption undergirding the anticipation of rampant pro- liferation is that states that abstain from nuclear weapons are resisting the dictates of their narrow self-interest—and that while this may be a laudable policy, it is also an unsustainable one. According to this line of thinking, sooner or later some external shock, such as an Iranian dash for the bomb, can be expected to jolt many states out of their nuclear self-restraint. -

Arguing for the Death Penalty: Making the Retentionist Case in Britain, 1945-1979

Arguing for the Death Penalty: Making the Retentionist Case in Britain, 1945-1979 Thomas James Wright MA University of York Department of History September 2010 Abstract There is a small body of historiography that analyses the abolition of capital punishment in Britain. There has been no detailed study of those who opposed abolition and no history of the entire post-war abolition process from the Criminal Justice Act 1948 to permanent abolition in 1969. This thesis aims to fill this gap by establishing the role and impact of the retentionists during the abolition process between the years 1945 and 1979. This thesis is structured around the main relevant Acts, Bills, amendments and reports and looks briefly into the retentionist campaign after abolition became permanent in December 1969. The only historians to have written in any detail on abolition are Victor Bailey and Mark Jarvis, who have published on the years 1945 to 1951 and 1957 to 1964 respectively. The subject was discussed in some detail in the early 1960s by the American political scientists James Christoph and Elizabeth Tuttle. Through its discussion of capital punishment this thesis develops the themes of civilisation and the permissive society, which were important to the abolition discourse. Abolition was a process that was controlled by the House of Commons. The general public had a negligible impact on the decisions made by MPs during the debates on the subject. For this reason this thesis priorities Parliamentary politics over popular action. This marks a break from the methodology of the new political histories that study „low‟ and „high‟ politics in the same depth. -

The Fallacy of Nuclear Deterrence

THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet JCSP 41 PCEMI 41 Exercise Solo Flight Exercice Solo Flight Disclaimer Avertissement Opinions expressed remain those of the author and Les opinons exprimées n’engagent que leurs auteurs do not represent Department of National Defence or et ne reflètent aucunement des politiques du Canadian Forces policy. This paper may not be used Ministère de la Défense nationale ou des Forces without written permission. canadiennes. Ce papier ne peut être reproduit sans autorisation écrite. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, représentée par represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2015. le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2015. CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE – COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 41 – PCEMI 41 2014 – 2015 EXERCISE SOLO FLIGHT – EXERCICE SOLO FLIGHT THE FALLACY OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE LCol J.P.P. Ouellet “This paper was written by a student “La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. It does not convenables au sujet. Elle ne reflète pas necessarily reflect the policy or the nécessairement la politique ou l'opinion opinion of any agency, including the d'un organisme quelconque, y compris le Government of Canada and the gouvernement du Canada et le ministère Canadian Department of National de la Défense nationale du Canada. -

Science, Technology and Medicine In

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/9781139044301.012 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Edgerton, D., & Pickstone, J. V. (2020). The United Kingdom. In H. R. Slotten, R. L. Numbers, & D. N. Livingstone (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Science: Modern Science in National, Transnational, and Global Context (Vol. 8, pp. 151-191). (Cambridge History of Science; Vol. 8). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139044301.012 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

A Chronology of World War Two in Many Ways the Most Effective Form of Index to the Newspaper Covered In

A Chronology of World War Two In many ways the most effective form of index to the newspaper covered in this project is a chronology of the period is a chronology of the period. After all, the newspapers all focused on the same basic news stories, responding as quickly as they could to the events happening around them. Of course, there were difficulties involved in communicating between London and the far flung frontiers of the war, or to imposed censorship. As a result, some stories are reported a day or more after the events themselves. Despite the fact that the news reporters attended the same briefings and were in receipt of the same official bulletins from their own independent reporters active in the warzones (some actually active behind enemy lines), with their own unsyndicated pictures, and with special articles commissioned and copyrighted by the papers. As such, a brief chronology of events serves to direct the reader to the issues covered by all or most of the newspapers, if not to the style or substance of the coverage. The chronology for each year begins with a brief summary of the major events of the year (in bold type), and a list of the books, films and records which appeared (in italic). There then follows a more detailed calendar of the events of the year. With regard to films, the initial year of release has been given as Hollywood columns often give detail of new films released in the States. Please note, however, that many were not released in Britain for another six to twelve months. -

Duncan Sandys, Unmanned Weaponry, and the Impossibility of Defence

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository 1 Nuclear Belief Systems and Individual Policy-Makers: Duncan Sandys, Unmanned Weaponry, and the Impossibility of Defence Lewis David Betts This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of East Anglia (School of History, Faculty of Arts and Humanities) November, 2014 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 This thesis attempts to explore the influence that Duncan Sandys' experiences of the Second World War had on his policy preferences, and policy-making, in relation to British defence policy during his years in government. This is a significant period in British nuclear policy which began with thermonuclear weaponry being placed ostentatiously at the centre of British defence planning in the 1957 Defence White Paper, and ended with the British acquiring the latest American nuclear weapon technology as a consequence of the Polaris Sales Agreement. It also saw intense discussion of the nature and type of nuclear weaponry the British government sought to wield in the Cold War, with attempts to build indigenous land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, and where British nuclear policy was discussed in extreme depth in government. The thesis explores this area by focusing on Duncan Sandys and examining his interaction with prominent aspects of the defence policy-making process. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

(C) Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/128/29 Image

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/128/29 Image Reference:0004 THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HER BRITANNIC MAJESTVS GOVERNMENT Printed for the Cabinet. April 1955 SECRET Copy No. fa CM. (55) 4m CABINET CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at 10 Downing Street, S.W. 1, on Tuesday, 19th April, 1955, at 11 a.m. Present: The Right Hon. Sir ANTHONY EDEN, M.P., Prime Minister. The Right Hon. R. A. BUTLER, M.P., The Right Hon. HAROLD MACMILLAN, Chancellor of the Exchequer. M.P., Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The Right Hon. VISCOUNT KILMUIR, The Right Hon. VISCOUNT WOOLTON, Lord Chancellor. Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. The Right Hon. H. F. C. CROOKSHANK, The Right Hon. GWILYM LLOYD- M.P., Lord Privy Seal. GEORGE, M.P., Secretary of State for the Home Department and Minister for Welsh Affairs. The Right Hon. JAMES STUART, M.P., The Right Hon. the EARL OF HOME, Secretary of State for Scotland. Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations. The Right Hon. A. T. LENNOX-BOYD, The Right Hon. Sir WALTER MONCKTON, M.P., Secretary of State for the Q.C., M.P., Minister of Labour and Colonies. National Service. The Right Hon. SELWYN LLOYD, Q.C., The Right Hon. DUNCAN SANDYS, M.P., M.P., Minister of Defence. Minister of Housing and Local Government. The Right Hon. PETER THORNEYCROFT, The Right Hon. D. HEATHCOAT AMORY, M.P., President of the Board of Trade. M.P., Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. The Right Hon. OSBERT PEAKE, M.P., Minister of Pensions and National Insurance.