Voices of Veterans Interview with Pete Salas Rocha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots

MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots by NATHANIEL S. PATCH n the morning of September 2, 1944, the submarine USS OFinback was floating on the surface of the Pacific Ocean—on lifeguard duty for any downed pilots of carrier-based fighters at- tacking Japanese bases on Bonin and Volcano Island. The day before, the Finback had rescued three naval avi- near Haha Jima. Aircraft in the area confirmed the loca- ators—a torpedo bomber crew—from the choppy central tion of the raft, and a plane circled overhead to mark the Pacific waters near the island of Tobiishi Bana during the location. The situation for the downed pilot looked grim; strikes on Iwo Jima. the raft was a mile and a half from shore, and the Japanese As dawn broke, the submarine’s radar picked up the in- were firing at it. coming wave of American planes heading towards Chichi Williams expressed his feelings about the stranded pilot’s Jima. situation in the war patrol report: “Spirits of all hands went A short time later, the Finback was contacted by two F6F to 300 feet.” This rescue would need to be creative because Hellcat fighters, their submarine combat air patrol escorts, the shore batteries threatened to hit the Finback on the sur- which submariners affectionately referred to as “chickens.” face if she tried to pick up the survivor there. The solution The Finback and the Hellcats were starting another day was to approach the raft submerged. But then how would of lifeguard duty to look for and rescue “zoomies,” the they get the aviator? submariners’ term for downed pilots. -

American Aces Against the Kamikaze

OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES® • 109 American Aces Against the Kamikaze Edward M Young © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES • 109 American Aces Against the Kamikaze © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE THE BEGINNING 6 CHAPTER TWO OKINAWA – PRELUDE TO INVASION 31 CHAPTER THREE THE APRIL BATTLES 44 CHAPTER FOUR THE FINAL BATTLES 66 CHAPTER FIVE NIGHTFIGHTERS AND NEAR ACES 83 APPENDICES 90 COLOUR PLATES COMMENTARY 91 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE BEGINNING CHAPTER ONE t 0729 hrs on the morning of 25 October 1944, radar on the escort carriers of Task Force 77.4.1 (call sign ‘Taffy 1’), cruising Aoff the Philippine island of Mindanao, picked up Japanese aeroplanes approaching through the scattered cumulous clouds. The carriers immediately went to General Quarters on what had already been an eventful morning. Using the clouds as cover, the Japanese aircraft managed to reach a point above ‘Taffy 1’ without being seen. Suddenly, at 0740 hrs, an A6M5 Reisen dived out of the clouds directly into the escort carrier USS Santee (CVE-29), crashing through its flightdeck on the port side forward of the elevator. Just 30 seconds later a second ‘Zeke’ dived towards the USS Suwannee (CVE-27), while a third targeted USS Petrof Bay (CVE-80) – anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire managed to shoot down both fighters. Then, at 0804 hrs, a fourth ‘Zeke’ dived on the Petrof Bay, but when hit by AAA it swerved and crashed into the flightdeck of Suwanee, blowing a hole in it forward of the aft elevator. -

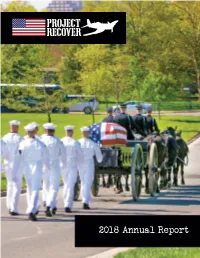

2018 Project Recover Annual Report

2018 Annual Report CONTENTS Introduction . 1. Bringing Our Heroes Home . 2. Research, Science & Technology . .6 Case File Development & Management . .8 Missions: Federated States of Micronesia . 12. Guatemala . 14. Hungary . .15 Solomon Islands . .16 Palau . .18 Kiska Island, AK . .20 Italy . .24 Kuwait . .28 Hands-on Education . .30 Communications & Media . .32 The Team . .34 Statistics Summary / Looking Ahead . .35 MISSION Project Recover is a collaborative effort to enlist 21st century science and technology in a quest to find and repatriate Americans missing in action since World War II, in order to provide recognition and closure for families and the Nation. Statement of Social Value: Project Recover is dedicated to searching for and locating American MIAs and POWs from conflicts around the world. Project Recover seeks to provide recognition, information and closure to families of these service members who have paid the ultimate sacrifice for our freedoms. More broadly, Project Recover provides a platform for educating the public about critical historical events, lost heroes who shaped our country and the importance of public service. Introduction Project Recover is a partnership among researchers Project Recover is now planning for the net phase of at the University of Delaware Scripps nstuon of operaons 2122 to connue using the best- Oceanography and Project Recover Inc. available science and technology, combined with historic and archival research, to bring American The project blends historical data from many sources service members home. to opmie search eorts with scanning sonars high denion cameras advanced diving and unmanned aerial and underwater roboc technologies. hese new methods are now being applied globally where service members are sll missing. -

Introduction August '43–February '44

Introduction DUE TO THE CRITICAL NEED FOR AIRCRAFT CARRIERS IN THE PACIFIC FORWARD AREA DURING THE EARLY PART OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, NINE SHIPS ORIGINALLY LAID DOWN FOR CONSTRUCTION AS LIGHT CRUISERS (CL) WERE REORDERED TO BE COMPLETED AS AIRCRAFT CARRIERS (CV) ON MARCH 18, 1942. THE ACTUAL DATES THAT EACH SHIP WAS CLASSIFIED CV VARIES. THE FIRST FIVE CARRIERS OF THE CLASS WERE COMMISSIONED AS CV'S. TO DISTINGUISH THEM FROM THE LARGER CARRIERS OF THE FLEET, THEY WERE AGAIN RECLASSIFIED ON JULY 15, 1943 AS CVL. THE REMAINING FOUR CARRIERS WERE COMMISSIONED AS CVL'S. THE INDEPENDENCE CLASS CARRIERS, AS THE CVL'S WERE KNOWN, WITH THEIR INTENDED LIGHT CRUISER NAMES FOLLOWS: 1. USS INDEPENDENCE CVL-22 USS AMSTERDAM CL-59 2. USS PRINCETON CVL-23 USS TALLAHASSEE CL-61 3. USS BELLEAU WOOD CVL-24 USS NEW HAVEN CL-76 4. USS COWPENS CVL-25 USS HUNTINGTON CL-77 5. USS MONTEREY CVL-26 USS DAYTON CL-78 6. USS LANGLEY CVL-27 USS FARGO CL-85 7. USS CABOT CVL -28 USS WILMINGTON CL-79 8. USS BATAAN CVL-29 USS BUFFALO CL-99 9. USS SAN JACINTO CVL-30 USS NEWARK CL-100 NOTE --- THE LANGLEY WAS FIRST CALLED CROWN POINT, AND THE SAN JACINTO WAS FIRST CALLED REPRISAL. THE INDEPENDENCE CLASS CARRIERS DISPLACED 11,000 TONS: 15,800 TONS FULL LOAD; OVERALL LENGTH, 623 FEET; BEAM, 71 1/2 FEET; WIDTH, 109 FEET; DRAFT 26 FEET; SPEED 33 + KNOTS; TWENTY-SIX 40MM AND FORTY 20MM AA MOUNTS, AIRCRAFT IN EXCESS OF 45. COMPLEMENT OF 1,569 MEN. -

February 2020 Patriot News

YYY E L L O W RRR I B B O N MMM INISTRY FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 12, ISSUE 2 CAVU Colonel Steve Martin Inside this Issue: Sitting by the sea, an old man lic service and he wanted to do thinks back over the course of his part for his country. At 18 Military Terms, Abbrevia- 1 his life – one unique in the years old, much to his parent’s tions, and Acronyms annals of history. He has chagrin, Bush became the young- lived a full life – loved and est naval aviator and was sent to CAVU 1-4 respected by many. He the Pacific. His parents thought Proposed New Dental Benefit 2, 4 watches the rhythm of the he was too young, and though sea with seagulls floating by tall, very skinny. He entered Winter Safety Tips (part 1) 2 on the ocean breeze. This is flight training to be a carrier pilot Valentine’s Day Military his favorite place in the specializing as a torpedo bomber. 3 Tribute world, out by the ocean. It’s peaceful and scenic and he CAVU – perfect flying conditions. Did You Know: Origins of Navy That was the note on the mission 3 thinks back over his life. He Terms, part 8 notices a small plaque he had board as the pilots had been briefed about their upcoming mis- This Month in Military History 4 placed at this very spot years ago. Once it was a motiva- sion on the morning of September tional symbol, pointing to 2, 1944. At 7:15 am, Lieutenant future possibilities; now it’s mostly a reminder Junior Grade (LTJG) George Bush was sitting of achievement gained, and a life well lived. -

Robert B. Stinnett Miscellaneous Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3c603258 No online items Inventory of the Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers Finding aid prepared by Jessica Lemieux and Chloe Pfendler Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008, 2014, 2021 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Robert B. 63006 1 Stinnett miscellaneous papers Title: Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers Date (inclusive): 1941-2015 Collection Number: 63006 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 120 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box(49.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Memoranda and photographs depicting the aircraft carrier San Jacinto, naval personnel, prisoner of war camps, life at sea, scenes of battle, naval artillery, Tokyo, and the Pacific Islands during World War II. Correspondence, interviews, and facsimiles of intelligence reports, dispatches, ciphers and other records related to research on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Creator: Stinnett, Robert B. Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Box 4 restricted. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1963. Additional material acquired in 2020. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Robert B. Stinnett miscellaneous papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Biographical Note Robert B. Stinnett was born March 31, 1924 in Oakland, California. During World War II, he served in the United States Navy as a photographer in the Pacific. -

Joint Force Quarterly Joint Education for the 21St Century a PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL by Robert B

0107 C1 3/4/04 7:02 AM Page 1 JOINT FORCEJFQ QUARTERLY East Asian Security Interservice Training Rwanda JFACC—The Next Step Battle for the Marianas Spring95 Uphold Democracy A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL 0207 Prelims 3/3/04 3:14 PM Page ii To have command of the air means to be in a position to prevent the enemy from flying while retaining the ability to fly oneself. —Giulio Douhet Cover 2 0207 Prelims 3/3/04 3:14 PM Page iii JFQ Page 1—no folio 0207 Prelims 3/3/04 3:14 PM Page 2 CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by John M. Shalikashvili Asia-Pacific Challenges 6 by Hans Binnendijk and Patrick M. Cronin JFQ FORUM A Commander in Chief Looks at East Asia 8 by Richard C. Macke JFQ The PLA: In Search of a Strategic Focus 16 by Ronald N. Montaperto Japan’s Emergent Security Policy 20 by Patrick M. Cronin Assessing the U.S.-North Korea 23 Agreement by Masao Okonogi South Korea’s Defense Posture 26 by Young-Koo Cha and Kang Choi Asian Multilateralism: Dialogue on Two Tracks PHOTO CREDITS 32 by Ralph A. Cossa The cover photograph shows USS San Jacinto with USS Barry (astern) transiting the Suez Canal (U.S. Navy/Dave Miller); the cover insets (from top) include Chinese honor guard (U.S. America and the Asia-Pacific Region Army/Robert W. Taylor); T–37 trainer (U.S. Air 37 by William T. Pendley Force); refugees in Goma, Zaire, during Opera- tion Support Hope (U.S. -

The Full Deck

Th e Full Deck Commander’s Message A special thanks goes out to everyone who attended Th e Valley Sail and Power Squad- ron’s Change of Watch. Th ere was great food, good company and a barrel of laughs. Th is event was extra special to me because this will be the 5th year since we were chartered. I am grateful for the nominating committee nominating me for another year and for my bridge offi cers committing to serve a full year of hard work. With their dedication and our collective team work I expect this year to be successful and full of accom- plishments. Our record has shown that anything we do we do to the best of our ability. One of the goals for this year is to have more activities planned. Th ese activities have been planned and organized according to the activities organizations calendar. Th e activities were well thought out in order to attract the interest of our members and potential new members. Th is yearly calendar may be found on our website for your perusal. We will also continue to off er an array of classes. Education is still one of our most important focuses. We understand that knowledge and confi - dence help to prevent dangerous consequences and builds up confi dence to practice safe boating. Boating is fun when it is safe. Smooth Waters, Cdr Kayenta George, S 2013 Watch Commander Kayenta George, S [email protected] Executive Offi cer Deborah Hoadley, AP [email protected] Administrative Offi cer Brian Krasnoff , P krasnoff @pacbell.net Education Offi cer Steve Dunn, AP [email protected] Treasurer Hal Hoadley, AP [email protected] Secretary Allan Lakin, SN [email protected] Executive Committee At Large Financial Review Committee Ken henry, SN Cheryl Dellepiane Reyna Henry, SN Don Dellepiane J. -

Sept. 15-21, 2020 Further Reproduction Or Distribution Is Subject to Original Copyright Restrictions

Weekly Media Report –Sept. 15-21, 2020 Further reproduction or distribution is subject to original copyright restrictions. ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… COVID-19: 1. Fit for Fight: Navies Challenged by COVID at Sea, Ashore (MarineLink 17 Sept 20) … Ned Lundquist Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, navies adjusted how they operate at home and while deployed, to keep their forces ready for any missions as they keep their Sailors, families, communities, as well as allies and partners safe from the coronavirus… the Naval War College in Newport R.I., is using tools like Zoom, Blackboard and Microsoft Teams for orientation and instruction. The summer quarter education at Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif, will be delivered via distance learning, although a small number of students will be allowed to perform lab work and research and take part in classified classes. For ships at sea, the number of safe ports to visit has been dramatically reduced. Guam in the Pacific and Rota, Spain in the Mediterranean are two examples of ports where the Navy already has a presence and can ensure compliance with COVID protocols. EDUCATION: 2. NPS Launches Distance Learning Graduate Certificate in Great Power Competition (Navy.mil 17 Sept 20) … Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Taylor Vencill The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) is launching a new distance learning graduate certificate in Great Power Competition (GPC), with the first cohort starting in January of 2021. With applications from active duty Navy and Marine Corps Officers being accepted now through September 28, School of International Graduate Studies officials anticipate the program’s open seats will fill quickly. -

Buck'' O'neil October 7, 2006 Remarks on the Situation In

Administration of George W. Bush, 2006 / Oct. 9 1767 Class John Delaney and Lieutenant JG Ted the 1836 Battle of San Jacinto. And in that White. On that day over Chichi Jima, a young battle, the free Texas forces led by Sam American became a war hero and learned Houston defeated a Mexican army that was an old lesson: With the defense of freedom much larger in size—and Sam Houston suc- comes loss and sacrifice. ceeded in capturing the Mexican general re- The George H.W. Bush honors a genera- sponsible for the slaughter of the Alamo just tion that valued service above self. Like so a few weeks before. Yet on the eve of the many who served in World War II, duty battle, the outcome was far from certain, and came naturally to our father. In the 4 years the Mexicans seemed to hold the advantage. of that war, 16 million Americans would put So Sam Houston called his Texans together, on the uniform, and the human costs were and he reminded them what they were fight- appalling. From the beaches of Normandy ing for. He told them: ‘‘Be men—be free to the jungles of Southeast Asia, more than men—that your children may bless their fa- 400,000 Americans would give their lives. ther’s name.’’ From the beginning of that war, there On this proud day, the children of George were those who argued that freedom had H.W. Bush bless their father’s name; the seen its day and that the future belonged to United States Navy honors his name; and the the hard men in Tokyo and Berlin. -

Vice President Bush Calls World War II Experience "Sobering"

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER 805 KIDDER BREESE SE -- WASHINGTON NAVY YARD WASHINGTON DC 20374-5060 Vice President Bush Calls World War II Experience "Sobering" Related Resource: LT George Bush, USNR By JO2 Timothy J Christmann Naval Aviation News 67 (March-April 1985): 12-15 Forty-one years ago, a 20-year-old Naval Aviator named George Bush embarked on a mission which he would later describe as one of the most dramatic moments of his life -- an experience which gave him a "sobering understanding of war and peace." "There's no question that it broadened my horizons," Vice President Bush said recently. "And there's no question that today it has a real impact on me as I give advice to the President." It was September 2, 1944. Lieutenant Junior Grade George Bush was a pilot with Torpedo Squadron Fifty-One (VT-51 ) aboard the aircraft carrier USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), a light carrier which was deployed in the North Pacific. Just two years earlier, on June 12, 1942, Bush had graduated from high school and joined the Navy as a seaman, second class. But, in less than a year, he completed flight training at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, was commissioned an ensign, and went on to fly TBM Avengers with VT-51. For a time, he was the youngest pilot in Naval Aviation. On that sunny morning of September, Bush woke aboard San Jacinto prepared to fly one of the 58 attack missions he would fly during the war. However, this particular mission would end a little differently than his other 57. -

2012 Summer Edition

2012 Summer Edition Commander General Commodore John Barry Memorial Report to the Order Marker Dedication In the last three months, The On May 4, 2012 the Commodore John Barry Memorial Marker Naval Order continues its was dedicated in Franklin Park, Washington DC. The Naval mission of preserving and Order teamed with the National Park Service to create a wayside promoting Naval History. marker to be placed alongside the statue of Commodore John Barry. Although the impressive statue has been standing since its dedication by President Woodrow Wilson in 1914, there has Admiral of the Navy been no interpretive marker to explain to the public who George Dewey Award Commodore John Barry was and why he is important today. Naval War College Professor John B. Hattendorf has been The statue and new marker is a memorial to Commodore Barry selected for the 2012 Admiral of the Navy George Dewey who was appointed senior captain upon the establishment of the Award. This award named for the Admiral who was the U.S. Navy, he commanded the frigate United States in the fourth Commander General of the Naval Order (1907-1917) Quasi-War is awarded to a senior civilian whose record of service sets with France. him apart among his peers. Prior awardees include President On February George H. Bush, Senator/Admiral Jeremiah Denton, 22, 1797, he Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon England, Secretary of was issued State George Shultz, Senator John Warner and Admiral Commission James Holloway. Number 1 by Professor Hattendorf is the President Ernest J. King Professor of George Maritime History at the Naval Washington, War College and is also the backdated to Chairman of the Maritime June 4, 1794.