MISSION: LIFEGUARD American Submarines in the Pacific Recovered Downed Pilots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiral William Frederick Halsey by Ruben Pang

personality profile 69 Admiral William Frederick Halsey by Ruben Pang IntRoductIon Early Years fleet admiral William halsey was born in elizabeth, frederick halsey (30 october new Jersey to a family of naval 1882 – 16 august 1959) was a tradition. his father was a captain united states navy (USN) officer in the USN. hasley naturally who served in both the first and followed in his footsteps, second World Wars (WWi and enrolling in the united states WWII). he was commander of (US) naval academy in 1900.3 the south pacific area during as a cadet, he held several the early years of the pacific extracurricular positions. he War against Japan and became played full-back for the football http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Halsey.JPG commander of the third fleet team, became president of the Fleet Admiral William Frederick Halsey for the remainder of the war, athletic association, and as during which he supported first classman “had his name general douglas macarthur’s engraved on the thompson advance on the philippines in trophy cup as the midshipman 1944. over the course of war, who had done most during halsey earned the reputation the year for the promotion of of being one of america’s most athletics.”4 aggressive fighting admirals, often driven by instinct over from 1907 to 1909, he gained intellect. however, his record substantial maritime experience also includes unnecessary losses while sailing with the “great at leyte gulf and damage to his White fleet” in a global third fleet during the typhoon circumnavigation.5 in 1909, of 1944 or “hasley’s typhoon,” halsey received instruction in the violent tempest that sank torpedoes with the reserve three destroyers and swept torpedo flotilla in charleston, away 146 naval aircraft. -

Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700873 No online items Register of the Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Processed by Don Walker; machine-readable finding aid created by Don Walker Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library, University of the Pacific Stockton, CA 95211 Phone: (209) 946-2404 Fax: (209) 946-2810 URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Library/Find/Holt-Atherton-Special-Collections.html © 1998 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Register of the Nimitz (Chester Mss144 1 W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Register of the Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, 1885-1962 Collection number: Mss144 Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library University of the Pacific Contact Information Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections University Library, University of the Pacific Stockton, CA 95211 Phone: (209) 946-2404 Fax: (209) 946-2810 URL: http://www.pacific.edu/Library/Find/Holt-Atherton-Special-Collections.html Processed by: Don Walker Date Completed: August 1998 Encoded by: Don Walker © 1998 University of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, Date (inclusive): 1885-1962 Collection number: Mss144 Creator: Extent: 0.5 linear ft. Repository: University of the Pacific. Library. Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections Stockton, CA 95211 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Nimitz (Chester W.) Collection, Mss144, Holt-Atherton Department of Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library Biography Chester William Nimitz (1885-1966) was Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. -

Spring 2018 Newsletter

OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE NEW MEXICO COUNCIL NAUTICAL NEWS NAVY LEAGUE OF THE UNITED STATES NM MARCH 1, 2018 www.nmnavyleague.com Spring 2018 Issue First Ever Underwater Ball-Handling Routine Page 1 By Mark Schaefer; Photo courtesy of Instagram Karen Thier - USS Santa Fe (SSN-763) and What do the Harlem Globetrotters, the USS Santa Fe (SSN-763) and ESPN have in the Harlem Globetrotters common? They all teamed up in a “Hoops for the Troops” game in celebration of Page 2 th the Globetrotters’ 75 anniversary of entertaining United States servicemen and - President’s Message: women. As part of the festivities, the USS Santa Fe hosted the first ever 2018 Goals & Priorities underwater ball-handling routine. This photo shows Navy Petty Officer Blake Thier Pages 3-5 on the submarine pier, as posted to Instagram by his mom. - Namesake Ships 75 Years of USS Santa Fe As part of the game, USS New Mexico Change of the entire audience Command was composed of U.S. Page 6 military personnel - Local New Mexico News and their families. BB-40 Ship’s Bell Update The event was hosted Teddy Roosevelt and the in conjunction with Navy League Navy Entertainment, Page 7 who partners with - Nautical Items of Interest the Globetrotters to Page 8 bring joy to military - Upcoming Events bases overseas each fall. Did you know that you can get the latest issues of Sea Power The Globetrotters conducted the underwater ball-handling routine (known as the magazine in an App? Go to your “Magic Circle”) aboard the USS Santa Fe submarine, and they also played a mobile device App Store and shooting game of N-A-V-Y with sailors aboard the deck of the USS Missouri search on “Navy League”. -

PVAO-Bulletin-VOL.11-ISSUE-2.Pdf

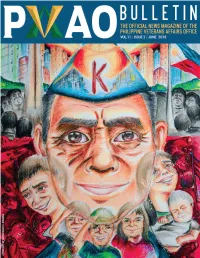

ABOUT THE COVER Over the years, the war becomes “ a reminder and testament that the Filipino spirit has always withstood the test of time.” The Official News Magazine of the - Sen. Panfilo “Ping” Lacson Philippine Veterans Affairs Office Special Guest and Speaker during the Review in Honor of the Veterans on 05 April 2018 Advisory Board IMAGINE A WORLD, wherein the Allied Forces in Europe and the Pacific LtGen. Ernesto G. Carolina, AFP (Ret) Administrator did not win the war. The very course of history itself, along with the essence of freedom and liberty would be devoid of the life that we so enjoy today. MGen. Raul Z. Caballes, AFP (Ret) Deputy Administrator Now, imagine at the blossoming age of your youth, you are called to arms to fight and defend your land from the threat of tyranny and oppression. Would you do it? Considering you have a whole life ahead of you, only to Contributors have it ended through the other end of a gun barrel. Are you willing to freely Atty. Rolando D. Villaflor give your life for the life of others? This was the reality of World War II. No Dr. Pilar D. Ibarra man deserves to go to war, but our forefathers did, and they did it without a MGen. Alfredo S. Cayton, Jr., AFP (Ret) moment’s notice, vouchsafing a peaceful and better world to live in for their children and their children’s children. BGen. Restituto L. Aguilar, AFP (Ret) Col. Agerico G. Amagna III, PAF (Ret) WWII Veteran Manuel R. Pamaran The cover for this Bulletin was inspired by Shena Rain Libranda’s painting, Liza T. -

THE HISTORY CHANNEL® and ENTERPRISE RENT-A-CAR® Partner to Bring BATTLE 360 to Viewers with Limited Commercial Interruption

THE HISTORY CHANNEL® AND ENTERPRISE RENT-A-CAR® PARTNER ON UNPRECEDENTED DEAL TO BRING BATTLE 360 TO VIEWERS WITH LIMITED COMMERCIAL INTERRUPTION Ten Episode Series Tells Story of USS Enterprise, the Historic World War II Aircraft Carrier Premieres Friday, February 29 at 10:00 p.m. ET/PT Series to Present 60 Second Messages from Jack Taylor, Founder of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, and a Veteran of the USS Enterprise All Other Battle 360 Episodes to Feature Exclusive Blended Entertainment Content Featuring In-Depth Interview with Taylor about His Experiences on USS Enterprise New York, NY, February 29, 2008 – The History Channel® and Enterprise Rent-A- Car today announced an unprecedented partnership that will allow for the entire ten- episode first season of Battle 360 to be seen with limited commercial interruption. The announcement was made by Mel Berning, Executive Vice President of Ad Sales, A&E Television Networks. Using the latest technology and animation to put viewers right in the middle of the action, Battle 360, which premieres Friday, February 29th at 10pm ET/PT, focuses on the USS Enterprise, an aircraft carrier that was front and center in nearly every major sea battle in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. The History Channel and Enterprise Rent-A- Car entered into the partnership as a unique way to honor Jack Taylor and his extraordinary life. The founder of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, Jack Taylor, flew combat missions off the decks of the USS Enterprise and earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses. Along with thousands of other members of the “Greatest Generation,” Taylor returned to civilian life and helped transform the United States into the world’s economic engine. -

August 2011 WWW

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF PERCH BASE, USSVI, PHOENIX, ARIZONA August 2011 WWW . PERCH - BASE . ORG Volume 17 - Issue 8 THE USSVI CREED GUIDES OUR EFFORTS AS PERCH BASE. SEE PAGE FOUR FOR THE FULL TEXT OF OUR CREED. A BOAT’S UNDERWATER “EYES” Featured Story It’s not a tube with prisms and mirrors any more! Page 11. What Else is “Below Decks” in the MidWatch Article Page Number Title and “What’s Below Decks”..................................................1 Less We Forget - Boats on Eternal Patrol..................................2 USSVI Creed - Our Purpose......................................................3 Perch Base Foundation Supporters...........................................3 Perch Base Offi cers...................................................................4 Sailing Orders (What’s happening with the Base)......................4 From the Wardroom - Base Commander’s Message.................5 Meeting Minutes - July 2011.......................................................5 Chaplain’s Column......................................................................8 “Binnacle List”.............................................................................8 What We’ve Been Up To.............................................................9 August Base Member Birthdays................................................10 What’s New Online....................................................................10 FEATURE: “A Boat’s Underwater Eye’s”......................................11 Lost Boat - USS Cochino (SS-345)..........................................13 -

Kamikazes! When Japanese Planes Attacked the U.S. Submarine Devilfish

KAMIKAZES! When Japanese Planes Attacked the U.S. Submarine Devilfish by NATHANIEL PATCH he image of desperate Japanese pilots purposely flying their Tplanes into American warships in the closing months of World War II figures prominently in American popular culture. When most people hear the term kamikaze, they think Fortunately, the Devilfish was close to the surface when of swarms of planes flying through a torrent of antiaircraft the explosion occurred, and the submarine took only mi fire and plowing into the decks of aircraft carriers, battle nor damage that the crew could control. ships, cruisers, and destroyers, taking the lives of sailors and The officers and crew in the control room took quick ac damaging or sinking the ships in this desperate act. tion to prevent the submarine from sinking and to mitigate Out of the hundreds of these attacks, one was quite un the damage done by the incoming saltwater. They leveled usual: the only kamikaze attack on an American subma off the submarine at 80 feet, and the drain pumps were rine, the USS Devilfish (SS 292). barely keeping up with the incoming water. The bilges of Why was this submarine attacked, and why was there the conning tower filled rapidly, and water began pouring only one attacker? The story of the attack on the Devilfish into the control room. A constant spray of saltwater from seems to be a fragment of a larger story, separated by time the conning tower splashed onto the electrical panels and and distance, occurring on March 20, 1945. If kamikazes consoles in the control room. -

Sea Poacher Association

SEA POACHER ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THOSE WHO SERVED ON THIS INCREDIBLE SUBMARINE! VOLUME 15, ISSUE 2 APRIL 2017 EDITOR: LANNY YESKE LTJG 61-63 PUBLISHER: BILL BRINKMAN EM 60-62 ____________________________________________________________________ LAST CALL NORFOLK 25 - 29 APRIL 2017 Our registered attendees as of March 1 include Lanny Yeske and Fran Zimmerman, Bill and Lin Brinkman, Deirdre Bridewell, Chuck and Bobbie Killgore, Dewey and Dottie Reed, Karl Schipper and Joan Carpenter, Robin Killgore and Ron Fischer, Joe Murdoch, Merlyn and Shirley Dorrheim, Richard Carney, Richard and Shirley Fox, Ivan and Marjorie Joslin with daughter Lessie Crosson, Ron Godwin, Larry and Arlene Weinfurter, Cecelia Thomas and Den- nis Marshall, Roy Purtell and Lisa Bereta, Jackie Wengrzyn and daughters Ranee Grady and Lyndsay Wengrzyn, Cal Cochrane and Vincent Sottile plus several dozen late signees. While there is still time, commitments are needed now so see the registration form and activities summary which follows. This promises to be another great reunion and Norfolk, as the City of Mermaids and Submarines, will certainly have some surprises. We are still very optimistic on visiting a nuclear submarine and will send out details when confirmed. Also in the loose ends department, consider bringing a contribution of whatever type for bidding at the silent auction and/or higher end items for the banquet auction which so far includes a vintage Seth Thomas 8-Day Key Wound Ship’s Bell Striking Clock graciously donated by Leo and Helen Carr. Other wise -

USSVI Thresher Base News September 2010 July 2010 Minutes the July Meeting of Thresher Base Treasurer’S Report - and Issues

USSVI Thresher Base News September 2010 July 2010 Minutes The July meeting of Thresher Base Treasurer’s Report - and issues. Due to concerns that arti- was held at the American Legion $4455.45 opening balance facts owned by many people may start Hall in Seabrook, NH on July 17. The $3490.19 current balance to disappear, he has been working on meeting was called to order followed $3229.19 Memorial Service balance details to create a nautical museum on by a silent prayer and pledge of al- special acknowledgement of $300 do- the seacoast. He has various meetings legiance. The Tolling of the Bells was nation from Vermont WWII base for scheduled and conducted for those boats lost in July memorial service and also a donation will announce and August. A silent prayer was said from Kurt Hoffman in memory of more details for those on eternal patrol. subvet James Rankin. when they are A sound off of those present was available. conducted - There were 95 people Old Business - none • John Car- present for this year’s lobsterbake. cioppolo Gary Hildreth introduced guests New Business - speaks to the Tom Shannon, D1 Commander, who • Base elections to be held at Septem- group about reminded everyone about elections ber meeting. Candidates are: his qualifica- and John Carcioppolo, Groton Base. Commander - Tom Young tions to be Special acknowledgement was given Sr. Vice Commander - Kevin Galeaz USSVI Com- to those Thresher family members in Jr. Vice Commander - Dennis mander. attendance: Jill and Lori Arsenault, O’Keeffe Mike Dinola, Sherely Abrams, Carol Treasurer - Dennis O’Keeffe continued on page 2 Norton, Paul Piva and Arlene Lelos. -

Subvets Picnic 2017 the Silent Sentinel, August 2017 2

Subvets Picnic 2017 The Silent Sentinel, August 2017 2 The Silent Sentinel, August 2017 3 USS Bullhead (SS-332) Lost on August 6,1945 with the loss of 84 crew members in the Lombok Strait while on her 3rd war patrol when sunk by a depth charge dropped by a Japanese Army p lane. Bullhead was the last submarine lost during WWII. USS Flier (SS-250) Lost on August 13,1944, with the loss of 78 crew members while on her 2nd war patrol. Flier was transiting on the surface when she was rocked by a massive explosion (probably a mine) and sank within less than a minute. 13 survivors, some injured, made it into the water and swam to shore. 8 survived and 6 days later friendly natives guided them to a Coast Watcher and they were evacuated by the USS Redfin (SS-272). USS S-39 (SS-144) Lost on August 13,1942 after grounding on a reef south of Rossel Island while on her 3rd war patrol. The entire crew was able to get off and rescued by the HMAS Katoomba. USS Harder (SS-257) Lost on August 24,1944 with the loss of 79 crew members from a depth charge attack by a minesweeper near Bataan while on her 6th war patrol. Harder had won a Presidential Unit Citation for her first 5 war patrols and CDR Dealey was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously. Harder is tied for 9th in the number of enemy ships sunk. The Silent Sentinel, August 2017 4 USS Cochino (SS-345) Lost on August 26, 1949 after being jolted by a violent polar gale off Norway caused an electrical fire and battery explosion that generated hydrogen and chlorine gasses. -

WRECK DIVING™ ...Uncover the Past Magazine

WRECK DIVING™ ...uncover the past Magazine Graf Zeppelin • La Galga • Mystery Ship • San Francisco Maru Scapa Flow • Treasure Hunting Part I • U-869 Part III • Ville de Dieppe WRECK DIVING MAGAZINE The Fate of the U-869 Reexamined Part III SanSan FranciscoFrancisco MaruMaru:: TheThe MillionMillion DollarDollar WreckWreck ofof TRUKTRUK LAGOONLAGOON Issue 19 A Quarterly Publication U-869 In In our previousour articles, we described the discovery and the long road to the identification ofU-869 off the The Fate Of New Jersey coast. We also examined the revised histories issued by the US Coast Guard Historical Center and the US Naval Historical Center, both of which claimed The U-869 the sinking was a result of a depth charge attack by two US Navy vessels in 1945. The conclusion we reached was that the attack by the destroyers was most likely Reexamined, Part on the already-wrecked U-869. If our conclusion is correct, then how did the U-869 come to be on the III bottom of the Atlantic? The Loss of the German Submarine Early Theories The most effective and successful branch of the German By John Chatterton, Richie Kohler, and John Yurga Navy in World War II was the U-boat arm. Hitler feared he would lose in a direct confrontation with the Royal Navy, so the German surface fleet largely sat idle at anchor. Meanwhile, the U-boats and their all- volunteer crews were out at sea, hunting down enemy vessels. They sank the merchant vessels delivering the Allies’ much-needed materials of war, and even were able to achieve some success against much larger enemy warships. -

American Aces Against the Kamikaze

OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES® • 109 American Aces Against the Kamikaze Edward M Young © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES • 109 American Aces Against the Kamikaze © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE THE BEGINNING 6 CHAPTER TWO OKINAWA – PRELUDE TO INVASION 31 CHAPTER THREE THE APRIL BATTLES 44 CHAPTER FOUR THE FINAL BATTLES 66 CHAPTER FIVE NIGHTFIGHTERS AND NEAR ACES 83 APPENDICES 90 COLOUR PLATES COMMENTARY 91 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com THE BEGINNING CHAPTER ONE t 0729 hrs on the morning of 25 October 1944, radar on the escort carriers of Task Force 77.4.1 (call sign ‘Taffy 1’), cruising Aoff the Philippine island of Mindanao, picked up Japanese aeroplanes approaching through the scattered cumulous clouds. The carriers immediately went to General Quarters on what had already been an eventful morning. Using the clouds as cover, the Japanese aircraft managed to reach a point above ‘Taffy 1’ without being seen. Suddenly, at 0740 hrs, an A6M5 Reisen dived out of the clouds directly into the escort carrier USS Santee (CVE-29), crashing through its flightdeck on the port side forward of the elevator. Just 30 seconds later a second ‘Zeke’ dived towards the USS Suwannee (CVE-27), while a third targeted USS Petrof Bay (CVE-80) – anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire managed to shoot down both fighters. Then, at 0804 hrs, a fourth ‘Zeke’ dived on the Petrof Bay, but when hit by AAA it swerved and crashed into the flightdeck of Suwanee, blowing a hole in it forward of the aft elevator.