An Interview with Dr. Richard J. Kessler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 1986 EDSA Revolution? These Are Just Some of the Questions That You Will Be Able to Answer As You Study This Module

What Is This Module About? “The people united will never be defeated.” The statement above is about “people power.” It means that if people are united, they can overcome whatever challenges lie ahead of them. The Filipinos have proven this during a historic event that won the admiration of the whole world—the 1986 EDSA “People Power” Revolution. What is the significance of this EDSA Revolution? Why did it happen? If revolution implies a struggle for change, was there any change after the 1986 EDSA Revolution? These are just some of the questions that you will be able to answer as you study this module. This module has three lessons: Lesson 1 – Revisiting the Historical Roots of the 1986 EDSA Revolution Lesson 2 – The Ouster of the Dictator Lesson 3 – The People United Will Never Be Defeated What Will You Learn From This Module? After studying this module, you should be able to: ♦ identify the reasons why the 1986 EDSA Revolution occurred; ♦ describe how the 1986 EDSA Revolution took place; and ♦ identify and explain the lessons that can be drawn from the 1986 EDSA Revolution. 1 Let’s See What You Already Know Before you start studying this module, take this simple test first to find out what you already know about this topic. Read each sentence below. If you agree with what it says, put a check mark (4) under the column marked Agree. If you disagree with what it says, put a check under the Disagree column. And if you’re not sure about your answer, put a check under the Not Sure column. -

Malacañang Says China Missiles Deployed in Disputed Seas Do Not

Warriors move on to face Rockets in West WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE SPORTS NEWS | A5 Vol. IX Issue 474 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Email: [email protected] Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 May 10 - 16, 2018 White House, some PH solons oppose China installing missiles Malacañang says China missiles deployed in Spratly By Macon Araneta in disputed seas do not target PH FilAm Star Correspondent By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent Malacañang’s reaction to the expressions of concern over the recent Chinese deploy- ment of missiles in the Spratly islands is one of nonchalance supposedly because Beijing said it would not use these against the Philippines and that China is a better source of assistance than America. Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said the improving ties between the Philippines and U.S. Press Sec. Sarah Sanders China is assurance enough that China will not use (Photo: www.newsx.com) its missiles against the Philippines. This echoed President Duterte’s earlier remarks when security The White House warned that China would experts warned that China’s installation of mis- face “consequences” for their leaders militarizing siles in the Spratly islands threatens the Philip- the illegally-reclaimed islands in the West Philip- pines’ international access in the disputed South pine Sea (WPS). China Sea. The installation of Chinese missiles were Duterte said China has not asked for any- reported on Fiery Reef, Subi Reef and Mischief thing in return for its assistance to the Philip- Reef in the Spratly archipelago that Manila claims pines as he allayed concerns of some groups over as its territory. -

Martial Law and the Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines (September 1972-February 1986): with a Case in the Province of Batangas

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No.2, September 1991 Martial Law and the Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines (September 1972-February 1986): With a Case in the Province of Batangas Masataka KIMURA* The imposition of martial lawS) by President Marcos In September 1972 I Introduction shattered Philippine democracy. The Since its independence, the Philippines country was placed under Marcos' au had been called the showcase of democracy thoritarian control until the revolution of in Asia, having acquired American political February 1986 which restored democracy. institutions. Similar to the United States, At the same time, the two-party system it had a two-party system. The two collapsed. The traditional political forces major parties, namely, the N acionalista lay dormant in the early years of martial Party (NP) and the Liberal Party (LP),1) rule when no elections were held. When had alternately captured state power elections were resumed in 1978, a single through elections, while other political dominant party called Kilusang Bagong parties had hardly played significant roles Lipunan (KBL) emerged as an admin in shaping the political course of the istration party under Marcos, while the country. 2) traditional opposition was fragmented which saw the proliferation of regional parties. * *MI§;q:, Asian Center, University of the Meantime, different non-traditional forces Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Metro Manila, such as those that operated underground the Philippines 1) The leadership of the two parties was composed and those that joined the protest movement, mainly of wealthy politicians from traditional which later snowballed after the Aquino elite families that had been entrenched in assassination in August 1983, emerged as provinces. -

Political Economy As Communication and Media Influence

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 325 685 CS 507 326 AUTHOR Oseguera, A. Anthony TITLE 1986 Philippine Elections: Political Economy as Communication and Media Influence. PUB DATE Nov 86 NOTE 75p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Speech and Communication Association (72nd, Chicago, IL, November 13-16, 1906). Best available copy. PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Elections; Foreign Countries; *Information Dissemination; *Mass Media Role; Media Research; *News Media; News Reporting; Political Issues IDENTIFIERS Filipinos; *Philippines; Political Communication; *Political Economics ABSTRACT This paper examines the Philippine transition of power as a communication event where the role of the print and electronic media is juxtaposed to cultural and political-economic determinants. The paper attempts to describe the similarities and differences between culture and communications in the Philippines and the United States. An historical-descriptive qualitative methodology is utilized. The paper uses selected stories that specify culture and political economy to glean the reality of what has transpired in the Philippines and the role the American and Philippine media, print and electronic, played both as observer and participant. Language and geography are considered principal elements of culture in the paper. The paper is taken from the content of a seminar in international broadcasting presently given at Eastern Illl.s.Ls University. (Seventy-five references are attached.) (Author/MG) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 1986 Philippine Elections 1 1986 Philippine Elections: Political Economy as Communication and Media Influence A. -

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: the Fall of Marcos

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: The Fall of Marcos Selena Gan Geok Hong A sub-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Relations) in the Department of International Relations, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra. June 1987 1 1 certify that this sub-thesis is my own original work and that all sources used have been acknowledged Selena Gan Geok Hong 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 Chapter One 14 Chapter Two 33 Chapter Three 47 Conclusion 62 Bibliography 68 2 Acknowledgements 1 would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Ron May and Dr Harold Crouch, both from the Department of Political and Social Change of the Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, for their advice and criticism in the preparation of this sub-thesis. I would also like to thank Dr Paul Real and Mr Geoffrey Jukes for their help in making my time at the Department of International Relations a knowledgeable one. I am also grateful to Brit Helgeby for all her help especially when I most needed it. 1 am most grateful to Philip Methven for his patience, advice and humour during the preparation of my thesis. Finally, 1 would like to thank my mother for all the support and encouragement that she has given me. Selena Gan Geok Hong, Canberra, June 1987. 3 Abbreviations AFP Armed Forces of the Philippines ASA Association of Southeast Asia ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations CG DK Coalition Government of Democratic -

Cardinal Jaime Sin Instrumental in the People’S Revolution

Cardinal Jaime Sin Instrumental in the People’s Revolution Jaime L. Sin (born 1928) was a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who served in the Philippines. He was instrumental in the defeat of the Marcos regime in 1986 (during the EDSA Revolution, aka People Power Revolution). Jaime L. Sin, was born in the town of New Washington, Aklan, in the Visayan Islands of the Philippines on August 21, 1928. He was the seventh of nine children of Juan Sin and Maxima Lachica. Cardinal Sin began his missionary career in Jaro, Iloilo, where he attended the Jaro Archdiocesan Seminary of St. Vincent Ferrer. He was ordained a priest on April 3, 1954. He served as priest of the Diocese of Capiz from 1954 to 1957 and became rector of St. Pius X Seminary in Roxas City from 1957 to 1967. While serving in the church he obtained a bachelor's degree in education from the Immaculate Concepcion College in 1959. He assumed several positions in archdioceses in the Visayan Islands—and subsequently became metropolitan archbishop of Manila, the capital of the Philippines, in 1974. Sin was named cardinal by Pope Paul VI on May 26, 1976. Cardinal Sin was known for his good sense of humor. He jokingly called his residence "the House of Sin" and smiled at the ironic combination of his name and title. But in a largely Catholic country plagued by a dictatorship from 1972 to 1986, Cardinal Sin often suppressed his smiles. He increasingly criticized the Marcos regime for its indifference to the plight of the poor. -

Remarks of Senator Bob Dole

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu Remarks of Senator Bob Dole AMERICAN TASK FORCE FOR LEBANON AWARDS DINNER Los Angeles, February 3, 1990 I AM TRULY HONORED TO RECEIVE THE PHILIP C. HABIB AWARD. IT HAPPENS THAT A MEMBER OF MY STAFF ONCE WORKED FOR PHIL HABIB --AL LEHN, HE'S HERE WITH ME TONIGHT. WHEN AL CAME TO WORK FOR ME, I WARNED HIM: GET READY FOR LONG HOURS, LOW PAY, NO PRAISE, AND PLENTY OF FLAK. HIS REPLY WAS: I AM READY -- I USED TO WORK FOR PHIL HABIB. Page 1 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 2 SO I DO APPRECIATE AN AWARD BEARING THIS DISTINGUISHED NAME. l'M ALSO HONORED TO BE FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF LAST YEAR'S RECIPIENT, SENATE MAJORITY LEADER GEORGE MITCHELL. HE'S A GREAT DEMOCRAT --1 HAPPEN TO BE A REPUBLICAN. EACH OF US IS PROUD OF OUR PARTY -- AND I --ADMIT IT: I WANT HIS JOB -- MAJORITY LEADER. Page 2 of 55 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 3 BUT ANY PARTISANSHIP WE HAVE IS TEMPERED BY A REAL FRIENDSHIP, AND BY MUTUAL RESPECT. AND WHEN IT COMES TO THE ISSUE OF LEBANON, GEORGE MITCHELL AND BOB DOLE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN, AND WILL CONTINUE TO BE, OF ONE MIND. 0 LIKE MANY OF YOU, l'VE COME A LONG WAY TO ATIEND TONIGHT'S DINNER. -

Since Aquino: the Philippine Tangle and the United States

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 6 - 1986 (77) SINCE AQUINO: THE PHILIPPINE • TANGLE AND THE UNITED STATES ••' Justus M. van der Kroef SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of o• MARylANd. c:. ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. -

SANCHEZ Final Defense Draft May 8

LET THE PEOPLE SPEAK: SOLIDARITY CULTURE AND THE MAKING OF A TRANSNATIONAL OPPOSITION TO THE MARCOS DICTATORSHIP, 1972-1986 BY MARK JOHN SANCHEZ DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History with a minor in Asian American Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Augusto Espiritu, Chair Professor Antoinette Burton Associate Professor Jose Bernard Capino Professor Kristin Hoganson Abstract This dissertation attempts to understand pro-democratic activism in ways that do not solely revolve around public protest. In the case of anti-authoritarian mobilizations in the Philippines, the conversation is often dominated by the EDSA "People Power" protests of 1986. This project discusses the longer histories of protest that made such a remarkable mobilization possible. A focus on these often-sidelined histories allows a focus on unacknowledged labor within social movement building, the confrontation between transnational and local impulses in political organizing, and also the democratic dreams that some groups dared to pursue when it was most dangerous to do so. Overall, this project is a history of the transnational opposition to the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines. It specifically examines the interactions among Asian American, European solidarity, and Filipino grassroots activists. I argue that these collaborations, which had grassroots activists and political detainees at their center, produced a movement culture that guided how participating activists approached their engagements with international institutions. Anti-Marcos activists understood that their material realities necessitated an engagement with institutions more known to them for their colonial and Cold War legacies such as the press, education, human rights, international law, and religion. -

Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974

Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 By Joseph Paul Scalice A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair Professor Peter Zinoman Professor Andrew Barshay Summer 2017 Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1957-1974 Copyright 2017 by Joseph Paul Scalice 1 Abstract Crisis of Revolutionary Leadership: Martial Law and the Communist Parties of the Philippines, 1959–1974 by Joseph Paul Scalice Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Jerey Hadler, Chair In 1967 the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (pkp) split in two. Within two years a second party – the Communist Party of the Philippines (cpp) – had been founded. In this work I argue that it was the political program of Stalinism, embodied in both parties through three basic principles – socialism in one country, the two-stage theory of revolution, and the bloc of four classes – that determined the fate of political struggles in the Philippines in the late 1960s and early 1970s and facilitated Marcos’ declaration of Martial Law in September 1972. I argue that the split in the Communist Party of the Philippines was the direct expression of the Sino-Soviet split in global Stalinism. The impact of this geopolitical split arrived late in the Philippines because it was initially refracted through Jakarta. -

WHAT's Inside

JULY-AUGUST• JULY-AUGUST 2009 2009 WHAT’S iNSIDE Gloria Arroyo, A Chilling After 20 Traveling Comparison Years, A Everything the The ghost of Recess Philippine head of the political past for the state does abroad has risen in the JVOAEJ is fair game for present A recess, the media not an end A DEATH LIKE NO OTHERn By Hector Bryant L. Macale HE PHILIPPINE press mirrored the nation’s collective grief over the passing of former Pres- ident Corazon “Cory” Aquino last Aug. 1. For at least a week, the death, wake and funeral of Aquino—who fought colon cancer for 16 Tmonths—overshadowed other stories such as Gloria Ma- capagal Arroyo’s recent US trip. Aquino’s death was like no other in recent history, reminding everyone not only of her role in the overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986, but also of the need to resist all forms of tyranny. Because of its significance as well as the context in which Aqui- no’s death occurred, the flood of men, women and children that filled the Manila Cathedral and the streets of the capital to catch a final glimpse of her sent not only a message of grief and gratitude. It also declared that Filipinos had not forgotten Cory Aquino’s singular role in removing a dic- tatorship, and implied that they resent the efforts by the Arroyo regime to amend the 1987 Consti- tution, thus validating the results of the numerous surveys that not Turn to page 14 Photos by LITO OCAMPO 2 • JULY-AUGUST 2009 editors’ NOTE PUBLISHED BY THE CENTER FOR MEDIA FREEDOM AND RESPONSIBILITY Melinda Quintos de Jesus Publisher Luis V. -

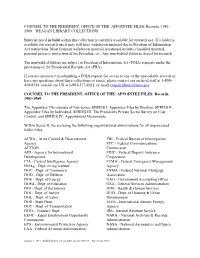

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept.