ASEAN-Philippine Relations: the Fall of Marcos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

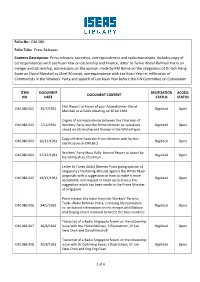

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

The 1986 EDSA Revolution? These Are Just Some of the Questions That You Will Be Able to Answer As You Study This Module

What Is This Module About? “The people united will never be defeated.” The statement above is about “people power.” It means that if people are united, they can overcome whatever challenges lie ahead of them. The Filipinos have proven this during a historic event that won the admiration of the whole world—the 1986 EDSA “People Power” Revolution. What is the significance of this EDSA Revolution? Why did it happen? If revolution implies a struggle for change, was there any change after the 1986 EDSA Revolution? These are just some of the questions that you will be able to answer as you study this module. This module has three lessons: Lesson 1 – Revisiting the Historical Roots of the 1986 EDSA Revolution Lesson 2 – The Ouster of the Dictator Lesson 3 – The People United Will Never Be Defeated What Will You Learn From This Module? After studying this module, you should be able to: ♦ identify the reasons why the 1986 EDSA Revolution occurred; ♦ describe how the 1986 EDSA Revolution took place; and ♦ identify and explain the lessons that can be drawn from the 1986 EDSA Revolution. 1 Let’s See What You Already Know Before you start studying this module, take this simple test first to find out what you already know about this topic. Read each sentence below. If you agree with what it says, put a check mark (4) under the column marked Agree. If you disagree with what it says, put a check under the Disagree column. And if you’re not sure about your answer, put a check under the Not Sure column. -

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines EDITED BY ARIES A. ARUGAY HERMAN JOSEPH S. KRAFT PUBLISHED BY University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies Diliman, Quezon City First Printing, 2020 UP CIDS No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publishers. Recommended Entry: Towards an enhanced strategic policy in the Philippines / edited by Aries A. Arugay, Herman Joseph S. Kraft. -- Quezon City : University of the Philippines, Center for Integrative Studies,[2020],©2020. pages ; cm ISBN 978-971-742-141-4 1. Philippines -- Economic policy. 2. Philippines -- Foreign economic relations. 2. Philippines -- Foreign policy. 3. International economic relations. 4. National Security -- Philippines. I. Arugay, Aries A. II. Kraft, Herman Joseph S. II. Title. 338.9599 HF1599 P020200166 Editors: Aries A. Arugay and Herman Joseph S. Kraft Copy Editors: Alexander F. Villafania and Edelynne Mae R. Escartin Layout and Cover design: Ericson Caguete Printed in the Philippines UP CIDS has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ______________________________________ i Foreword Stefan Jost ____________________________________________ iii Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem _____________________________v List of Abbreviations ___________________________________ ix About the Contributors ________________________________ xiii Introduction The Strategic Outlook of the Philippines: “Situation Normal, Still Muddling Through” Herman Joseph S. Kraft __________________________________1 Maritime Security The South China Sea and East China Sea Disputes: Juxtapositions and Implications for the Philippines Jaime B. -

Naval Reserve Command

NAVAL RESERVE OFFICER TRAINING CORPS Military Science –1 (MS-1) COURSE ORIENTATION Training Regulation A. Introduction: The conduct of this training program is embodied under the provisions of RA 9163 and RA 7077 and the following regulations shall be implemented to all students enrolled in the Military Science Training to produce quality enlisted and officer reservists for the AFP Reserve Force. B. Attendance: 1. A minimum attendance of nine (9) training days or eighty percent (80%) of the total number of ROTC training days per semester shall be required to pass the course. 2. Absence from instructions maybe excuse for sickness, injury or other exceptional circumstances. 3. A cadet/ cadette (basic/advance) who incurs an unexcused absence of more than three (3) training days or twenty percent (20%) of the total number of training during the semester shall no longer be made to continue the course during the school year. 4. Three (3) consecutive absences will automatically drop the student from the course. C. Grading: 1. The school year which is divided into two (2) semesters must conform to the school calendar as practicable. 2. Cadets/ cadettes shall be given a final grade for every semester, such grade to be computed based on the following weights: a. Attendance - - - - - - - - - - 30 points b. Military Aptitude - - - - - 30 points c. Subject Proficiency - - - - 40 points 3. Subject proficiency is forty percent (40%) apportioned to the different subjects of a course depending on the relative importance of the subject and the number of hours devoted to it. It is the sum of the weighted grades of all subjects. -

OH-323) 482 Pgs

Processed by: EWH LEE Date: 10-13-94 LEE, WILLIAM L. (OH-323) 482 pgs. OPEN Military associate of General Eisenhower; organizer of Philippine Air Force under Douglas MacArthur, 1935-38 Interview in 3 parts: Part I: 1-211; Part II: 212-368; Part III: 369-482 DESCRIPTION: [Interview is based on diary entries and is very informal. Mrs. Lee is present and makes occasional comments.] PART I: Identification of and comments about various figures and locations in film footage taken in the Philippines during the 1930's; flying training and equipment used at Camp Murphy; Jimmy Ord; building an airstrip; planes used for training; Lee's background (including early duty assignments; volunteering for assignment to the Philippines); organizing and developing the Philippine Air Unit of the constabulary (including Filipino officer assistants; Curtis Lambert; acquiring training aircraft); arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and staff (October 26, 1935); first meeting with Major Eisenhower (December 14, 1935); purpose of the constabulary; Lee's financial situation; building Camp Murphy (including problems; plans for the air unit; aircraft); Lee's interest in a squadron of airplanes for patrol of coastline vs. MacArthur's plan for seapatrol boats; Sid Huff; establishing the air unit (including determining the kind of airplanes needed; establishing physical standards for Filipino cadets; Jesus Villamor; standards of training; Lee's assessment of the success of Filipino student pilots); "Lefty" Parker, Lee, and Eisenhower's solo flight; early stages in formation -

A/64/742–S/2010/181 General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/64/742–S/2010/181 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 April 2010 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-fourth session Sixty-fifth year Agenda item 65 (a) Promotion and protection of the rights of children Children and armed conflict Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report, which covers the period from January to December 2009, is submitted pursuant to paragraph 19 of Security Council resolution 1882 (2009), by which the Council requested me to submit a report on the implementation of that resolution, resolutions 1261 (1999), 1314 (2000), 1379 (2001), 1460 (2003), 1539 (2004) and 1612 (2005), as well as its presidential statements on children and armed conflict. 2. The first part of the report (section II) includes information on measures undertaken by parties listed in the annexes to end all violations and abuses committed against children in armed conflict that serve as indicators of progress made in follow-up to the recommendations of the Security Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict. The second part (section III) contains an update on the implementation of the monitoring and reporting mechanism established by the Council in its resolution 1612 (2005). The third part (section IV) of the report focuses on information on grave violations committed against children, in particular recruitment and use of children, killing and maiming of children, rape and other sexual violence against children, abductions of children, attacks on schools and -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

Factors Influencing Purchase Intention Towards Dietary Supplement Products Among Young

Running head: FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 1 Factors Influencing Purchase Intention towards Dietary Supplement Products among Young Adults Lee Jia Hou, Lim Kwoh Fronn, and Yong Kai Yun Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 2 Abstract This study aimed to explore the factors affecting young adults‟ purchase intention towards dietary supplement products. These factors included attitude towards consuming dietary supplements, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, as well as demographic characteristics such as gender, income, and residential area. 300 respondents were equally recruited from the internet and also UTAR, Kampar campus to complete the questionnaire. Findings concluded that perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude significantly predicted the purchase intention of dietary supplement products. Among these variables, subjective norms was the strongest predictor. Besides that, demographic characteristic such as gender difference was found significant in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. In contrast, there was no significant difference found between types of residential area in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. A significant and positive relationship between income and purchase intention was discovered. The findings strengthened the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of predicting purchase intention of dietary supplement products among young adults. Subjective norms, being the most significant predictor of purchase intention could also be constructive for marketers to effectively publicize dietary supplement use. Keywords: young adults, purchase intention, dietary supplement products, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background of study Health care related issues, ranging from increasing rates of chronic diseases, reduced life expectancy and growing health care expenses are common globally. -

Malacañang Says China Missiles Deployed in Disputed Seas Do Not

Warriors move on to face Rockets in West WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE SPORTS NEWS | A5 Vol. IX Issue 474 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Email: [email protected] Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 May 10 - 16, 2018 White House, some PH solons oppose China installing missiles Malacañang says China missiles deployed in Spratly By Macon Araneta in disputed seas do not target PH FilAm Star Correspondent By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent Malacañang’s reaction to the expressions of concern over the recent Chinese deploy- ment of missiles in the Spratly islands is one of nonchalance supposedly because Beijing said it would not use these against the Philippines and that China is a better source of assistance than America. Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said the improving ties between the Philippines and U.S. Press Sec. Sarah Sanders China is assurance enough that China will not use (Photo: www.newsx.com) its missiles against the Philippines. This echoed President Duterte’s earlier remarks when security The White House warned that China would experts warned that China’s installation of mis- face “consequences” for their leaders militarizing siles in the Spratly islands threatens the Philip- the illegally-reclaimed islands in the West Philip- pines’ international access in the disputed South pine Sea (WPS). China Sea. The installation of Chinese missiles were Duterte said China has not asked for any- reported on Fiery Reef, Subi Reef and Mischief thing in return for its assistance to the Philip- Reef in the Spratly archipelago that Manila claims pines as he allayed concerns of some groups over as its territory. -

Exhibition Brochure 2

You CAn not Bite Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite Pio Abad I have thought since about this lunch a great deal. The wine was chilled and poured into crystal glasses. The fish was served on porcelain plates that bore the American eagle. The sheepdog and the crystal and the American eagle together had on me a certain anesthetic effect, temporarily deadening that receptivity to the sinister that afflicts everyone in Salvador, and I experienced for a moment the official American delusion, the illusion of plausibility, the sense that the American undertaking in El Salvador might turn out to be, from the right angle, in the right light, just another difficult but possible mission in another troubled but possible country. —Joan Didion1 SEACLIFF At my mother’s wake two years ago, I found out that she was adept 1. Joan Didion, at assembling a rifle. I have always been aware of her radical past Salvador but there are certain details that have only surfaced recently. The (Vintage: 1994), intricacies of past struggles had always surrendered to the urgen- 112, pp. 87-88. cies of present ones. My parents were both working as labor organizers when they met in the mid-70s. Armed with Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals (1971) and Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), they would head to the fishing communities on the outskirts of Manila to assist fishermen, address their livelihood issues and educate them on the political climate of the country. It was this solidarity work and their eventual involvement in the democratic socialist movement that placed them within the crosshairs of Ferdinand Marcos’ military. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

xxxui CHRONOLOGY í-i: Sudan. Elections to a Constituent Assembly (voting postponed for 37 southern seats). 4 Zambia. Basil Kabwe became Finance Minister and Luke Mwan- anshiku, Foreign Minister. 5-1: Liberia. Robert Tubman became Finance Minister, replacing G. Irving Jones. 7 Lebanon. Israeli planes bombed refugee camps near Sidon, said to contain PLO factions. 13 Israel. Moshe Nissim became Finance Minister, replacing Itzhak Moda'i. 14 European Communities. Limited diplomatic sanctions were imposed on Libya, in retaliation for terrorist attacks. Sanctions were intensified on 22nd. 15 Libya. US aircraft bombed Tripoli from UK and aircraft carrier bases; the raids were said to be directed against terrorist head- quarters in the city. 17 United Kingdom. Explosives were found planted in the luggage of a passenger on an Israeli aircraft; a Jordanian was arrested on 18 th. 23 South Africa. New regulations in force: no further arrests under the pass laws, release for those now in prison for violating the laws, proposed common identity document for all groups of the population. 25 Swaziland. Prince Makhosetive Dlamini was inaugurated as King Mswati III. 26 USSR. No 4 reactor, Chernobyl nuclear power station, exploded and caught fire. Serious levels of radio-activity spread through neighbouring states; the casualty figure was not known. 4 Afghánistán. Mohammad Najibollah, head of security services, replaced Babrak Karmal as General Secretary, People's Demo- cratic Party. 7 Bangladesh. General election; the Jatiya party won 153 out of 300 elected seats. 8 Costa Rica. Oscar Arias Sánchez was sworn in as President. Norway. A minority Labour government took office, under Gro 9 Harlem Brundtland. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ......................................................................................