Malaysian Parliament 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

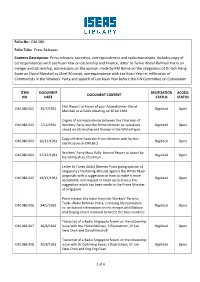

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

Malaysia's Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Malaysia’s Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern Thailand, Aceh and the Moro Region: The Ethnic Dimension Jafri Abdul Jalil A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations 2008 UMI Number: U615917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615917 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Libra British U to 'v o> F-o in andEconor- I I ^ C - 5 3 AUTHOR DECLARATION I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Jafri Abdul Jalil The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without prior consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

Vol. 81: Nov/Dec 19 | TEST Engineering & Management

8/12/2020 Vol. 81: Nov/Dec 19 | TEST Engineering & Management Register Login Current Archives About Search Home / Archives / Vol. 81: Nov/Dec 19 Vol. 81: Nov/Dec 19 Publication Issue: Vol 81: Nov/Dec 19 Issue Publication Date: 31 December 2019 Articles Implementation of Multi-object Recognition Algorithm Using Enhanced R-CNN Hyochang Ahn, June-Hwan Lee, Han-Jin Cho 01 - 08 PDF The Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Startup Performance of Technology-Based Startup Companies - Focusing on the transformational leadership mediating effect- Tae-Ho You, Yen-Yoo You 09 - 15 PDF Software-Defined ScienceDMZ Construction using SDN/ScienceDMZ/Edge Computing for High Performance Big Data Transformation Ki-Hyeon Kim, Dongkyun Kim, Yong-Hawn Kim 16 - 25 PDF Golf career or message letter type influences on the choice of take-out coffee with message appeals on golf courses testmagzine.biz/index.php/testmagzine/issue/view/6 1/116 8/12/2020 Vol. 81: Nov/Dec 19 | TEST Engineering & Management Jaeyoung Yoon, Yongchel Kwon, Gwi-Gon Kim 26 - 34 PDF An Examination on Competitiveness Analysis of Huawei Enterprise Jin-Hee Kim, Myeong-Cheol Choi 35 - 41 PDF A Semantic Classification of Images by Predicting Emotional Concepts from Visual Features Tamil Priya.D, Divya Udayan.J 42 - 70 PDF An Examination on the Effect of Customer Characteristics on Long-term Relationship Orientation for Consultants-Focusing on the mediating effect of relational embeddedness Mi-Sun Eom, Yen-Yoo You 71 - 77 PDF Tensile strength improvement of FDMed ABS parts by a WIP -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

Dewan Rakyat

Bil. 41 Khamis 25 Julai 1996 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN KESEMBILAN PENGGAL KEDUA MESYUARAT KEDUA KANDUNGAN JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 1] USUL-USUL: Menangguhkan Mesyuarat Di Bawah Peraturan Mesyuarat 18 - Peguam Negara-Pendakwaan Terhadap Menteri Perdagangan Antarabangsa dan lndustri -Y.B. Tuan Lim Guan Eng (Kota Me'iaka) [Ruangan 17] Waktu Mesyuarat dan Urusan Dibebaskan Daripada Peraturan Mesyuarat Mengikut Peraturan 16(3) [Ruangan 97] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Lembaga Kemajuan Wilayah Jengka (Pindaan) 1996 [Ruangan 20] Rang Undang-undang Pengangkutan Jalan (Pindaan) 1996 [Ruangan 60] UCAPAN PENANGGUHAN: Kempen Inflasi Sifar -Y.B. Tuan Lim Guan Eng (Kota Melaka) [Ruangan 97] Ditcrhit olch: CAWANGAN DOKUMENTASI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 2!KHl 25 JULAI 1996 AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATo' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, OATo' SERI OR. MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, D.K.I., D.U.K., S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.I.S. (Kubang Pasu). Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Kewangan, DATo' SERI ANWAR BIN IBRAHIM, D.U.P.N., S.S.A.P., S.S.S.A., D.G.S.M., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., D.M.P.N. (Permatang Pauh). -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Factors Influencing Purchase Intention Towards Dietary Supplement Products Among Young

Running head: FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 1 Factors Influencing Purchase Intention towards Dietary Supplement Products among Young Adults Lee Jia Hou, Lim Kwoh Fronn, and Yong Kai Yun Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 2 Abstract This study aimed to explore the factors affecting young adults‟ purchase intention towards dietary supplement products. These factors included attitude towards consuming dietary supplements, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, as well as demographic characteristics such as gender, income, and residential area. 300 respondents were equally recruited from the internet and also UTAR, Kampar campus to complete the questionnaire. Findings concluded that perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude significantly predicted the purchase intention of dietary supplement products. Among these variables, subjective norms was the strongest predictor. Besides that, demographic characteristic such as gender difference was found significant in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. In contrast, there was no significant difference found between types of residential area in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. A significant and positive relationship between income and purchase intention was discovered. The findings strengthened the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of predicting purchase intention of dietary supplement products among young adults. Subjective norms, being the most significant predictor of purchase intention could also be constructive for marketers to effectively publicize dietary supplement use. Keywords: young adults, purchase intention, dietary supplement products, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background of study Health care related issues, ranging from increasing rates of chronic diseases, reduced life expectancy and growing health care expenses are common globally. -

Attachment As a Predictor of University Adjustment Among Freshmen: Evidence from a Malaysian Public University

Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 111 ATTACHMENT AS A PREDICTOR OF UNIVERSITY ADJUSTMENT AMONG FRESHMEN: EVIDENCE FROM A MALAYSIAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY 1Walton Wider, 2Mazni Mustapha, 3Murnizam Halik & 4Ferlis Bahari 1Faculty of Arts and Social Science Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia 2-3Faculty of Psychology and Education Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 4Psychology and Social Health Research Unit Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 1Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Purpose – Building upon attachment theory and emerging theory, the current study was aimed at examining the effect of peer attachment in predicting adjustment to life in university among freshmen in a public unirvsity in East Malaysia. Furthermore, it sought to examine the influence of gender and perceived-adult status as moderators of the relationship between student attachment and student adjustment. Methodology – Data was collected from 557 freshmen in one of the public universities in East Malaysia. Two questionnaires, namely The Inventory of Parent and Peers Attachment (IPPA) and The Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ) were used in this study. Partial Least Square (PLS) analysis was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships. Findings – The findings of the study showed that peer trust positively influenced academic and social adjustment. Meanwhile, peer communication positively influenced social adjustment, but negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment. Lastly, peer alienation negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment, but positively influenced institutional attachment. The Partial Least 112 Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 Square - Multi Group Analysis (PLS-MGA) results indicated no significant differences in peer attachment and university adjustment across gender and perceived-adult status. -

A Abang-Adik Relationship, 85 Abdul Ghani Othman, 133 Abdul Rahman

Index 265 INDEX A ASEAN Post-Ministerial Conference abang-adik relationship, 85 (PMC), 182 Abdul Ghani Othman, 133 ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), 182 Abdul Rahman, Tunku see Tunku Asia Europe Meeting (ASEM), 222 Abdul Rahman Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Abdul Razak bin Hussein, 3, 44 (APEC), 182, 222 Abdullah Ahmad, 107 Asian Development Bank, 201 Abdullah Badawi, 4, 47 Asian Development Outlook, 201 cancellation of bridge project, 133 Asian economic crisis Abdullah Sungkar, 192 responses, 220, 221 Abu Bakar Basyir, 192 Asian financial crisis, 46, 143 Abu Bakar Association of Southeast Asian Nations son of Temenggung Ibrahim, 34 (ASEAN), 144 Abu Sayaff group, 193 avian flu, 48 Air Asia Azalina Othman Said, 131 components of, 100 use of Johor as hub, 135 B Al-Hazmi, Nawaf, 192 Baitulmal (Alms Collection Agency), Al-Midhar, Khalid, 192 188 Al-Mukmin Islamic School, 192 Bank Negara Malaysia Al-Qaeda networks, 192 allowing foreign ownership in All-Malaya Council of Joint Action Islamic Banks, 202 (AMCJA), 40 Barisan Sosialis, 65, 141 Alliance Party, 6 fear of it assuming power in UMNO-led, 41 Singapore, 102 AMCJA-PUTERA alliance formation, 101 People’s Constitional Proposal for merger campaign, 56, 57 Malaya, 40 bilateral relationship anak raja, 31 effect of leadership, 143 Anderson, John, 95 major issues, 84, 85 Anglo-Dutch Treaty, 127 bilateral trade, 213, 214 Anglo-Malayan Defence Agreement Binnell, T., 135 (AMDA), 146, 164, 171, 180 Bourdillon, H.T., 13 ASEAN Community Brassey, Lord, 41 goal of creating, 89 bridge issue, 47 ASEAN Declaration -

A Legal Framework for Outer Space Activities in Malaysia Tunku Intan Mainura Faculty of Law, University Teknologi Mara,40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM) ||Volume||06||Issue||04||Pages||SH-2018-81-90||2018|| Website: www.ijsrm.in ISSN (e): 2321-3418 Index Copernicus value (2015): 57.47, (2016):93.67, DOI: 10.18535/ijsrm/v6i4.sh03 A Legal Framework for Outer Space Activities in Malaysia Tunku Intan Mainura Faculty of Law, university teknologi Mara,40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia Introduction 7 One common similarity that Malaysia has between and space education programme . In order for itself and the international space programme1 is the Malaysia to ensure that its activities under the year 1957. For Malaysia it was the year of programme of space science and technology can be Independence2 and for the international space effectively undertaken, Malaysia has built space infrastructures, which includes the national programme, the first satellite, Sputnik 1, was 8 launched to outer space by the Soviet Union observatory and remote sensing centres . Activities (USSR)3. That was 56 years ago. Today outer space under the space science and technology programme is familiar territory to states at large and Malaysia is includes the satellite technology activities. Under one of the players in this arena4. Although it has this activity, Malaysia has participated in it by been commented by some writers that ‘Malaysia having six satellites in orbit. Nevertheless, these can be considered as new in space activities, since satellites were not launched from Malaysia’s territory, as Malaysia does not have a launching its first satellite was only launched into orbit in 9 1997’5, nevertheless, it should be highlighted here facility .