Attachment As a Predictor of University Adjustment Among Freshmen: Evidence from a Malaysian Public University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

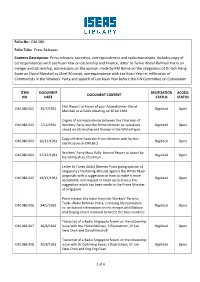

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

Factors Influencing Purchase Intention Towards Dietary Supplement Products Among Young

Running head: FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 1 Factors Influencing Purchase Intention towards Dietary Supplement Products among Young Adults Lee Jia Hou, Lim Kwoh Fronn, and Yong Kai Yun Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 2 Abstract This study aimed to explore the factors affecting young adults‟ purchase intention towards dietary supplement products. These factors included attitude towards consuming dietary supplements, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, as well as demographic characteristics such as gender, income, and residential area. 300 respondents were equally recruited from the internet and also UTAR, Kampar campus to complete the questionnaire. Findings concluded that perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude significantly predicted the purchase intention of dietary supplement products. Among these variables, subjective norms was the strongest predictor. Besides that, demographic characteristic such as gender difference was found significant in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. In contrast, there was no significant difference found between types of residential area in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. A significant and positive relationship between income and purchase intention was discovered. The findings strengthened the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of predicting purchase intention of dietary supplement products among young adults. Subjective norms, being the most significant predictor of purchase intention could also be constructive for marketers to effectively publicize dietary supplement use. Keywords: young adults, purchase intention, dietary supplement products, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background of study Health care related issues, ranging from increasing rates of chronic diseases, reduced life expectancy and growing health care expenses are common globally. -

Malaysian Parliament 1965

Official Background Guide Malaysian Parliament 1965 Model United Nations at Chapel Hill XVIII February 22 – 25, 2018 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director ………………………………………………………………… 3 Letter from the Chair ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Background Information ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Background: Singapore ……………………………………………………… 5 Background: Malaysia ……………………………………………………… 9 Identity Politics ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Radical Political Parties ………………………………………………………………………… 14 Race Riots ……………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Positions List …………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Endnotes ……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Parliament of Malaysia 1965 Page 2 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Malaysian Parliament of 1965 Committee at the Model United Nations at Chapel Hill 2018 Conference! My name is Annah Bachman and I have the honor of serving as your Crisis Director. I am a third year Political Science and Philosophy double major here at UNC-Chapel Hill and have been involved with MUNCH since my freshman year. I’ve previously served as a staffer for the Democratic National Committee and as the Crisis Director for the Security Council for past MUNCH conferences. This past fall semester I studied at the National University of Singapore where my idea of the Malaysian Parliament in 1965 was formed. Through my experience of living in Singapore for a semester and studying its foreign policy, it has been fascinating to see how the “traumatic” separation of Singapore has influenced its current policies and relations with its surrounding countries. Our committee is going back in time to just before Singapore’s separation from the Malaysian peninsula to see how ethnic and racial tensions, trade policies, and good old fashioned diplomacy will unfold. Delegates should keep in mind that there is a difference between Southeast Asian diplomacy and traditional Western diplomacy (hint: think “ASEAN way”). -

Parliamentary Debates

Volume III Tuesday No. 41 30 January, 1962 ~J*\ PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RA'AYAT (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES) OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS EXEMPTED BUSINESS (MOTION) [Col. 4320] BILL- The Constitution (Amendment) Bill (continuation) [Col. 4269] OI~TERBITKAN OLER THOR BENG CHONG, A.M.N., PEMANGKU PENCHETAIC ICEIVJAAN PERSEKlM'UAN TANAH MELA.YU 1962 Harga: $1 FEDERATION OF MALAYA DEWAN RA'AYAT (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES) Official Report Third Session of the First Dewan Ra'ayat Tuesday, 30th January, 1962 The House met at Ten o'clock a.m. PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. Speaker, DATO' HAJI MOHAMED NOAH BIN OMAR, S.P.M.J., D.P.M.B., P.I.S., J.P. the Prime Minister and Minister of External Affairs, Y.T.M. TuNKU ABDUL RAHMAN PuTRA AL-HAJ, K.O.M. (Kuala Kedah). the Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Defence and Minister of Rural Development, TuN HAn ABDUL RAZAK BIN DATO' HUSSAIN, S.M.N. (Pekan). the Minister of Internal Security and Minister of the Interior. DATO' DR. ISMAIL BIN DATO' HAJI ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N. (Johor Timor). the Minister of Finance, ENCHE' TAN Srnw SIN. J.P. (Melaka Tengah). the Minister of Works, Posts and Telecommunications, DATO' v. T. SAMBANTHAN, P.M.N. (Sungai Siput). the Minister without Portfolio, DATO' SULEIMAN BIN DATO' HAJI ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N. (Muar Selatan). the Minister of Transport, DATO' SARDON BIN HAJI JuBIR, P.M.N. (Pontian Utara). the Minister of Commerce and Industry, ENCHE' MOHAMED KHIR mN JoHARI (Kedah Tengah). the Minister of Labour, ENcHE' BAHAMAN BlN SAMSUDIN (Kuala Pilah). the Minister of Education, ENCHE' ABDUL RAHMAN BIN HAJI TALIB (Kuantan). -

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: the Fall of Marcos

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: The Fall of Marcos Selena Gan Geok Hong A sub-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Relations) in the Department of International Relations, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra. June 1987 1 1 certify that this sub-thesis is my own original work and that all sources used have been acknowledged Selena Gan Geok Hong 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 Chapter One 14 Chapter Two 33 Chapter Three 47 Conclusion 62 Bibliography 68 2 Acknowledgements 1 would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Ron May and Dr Harold Crouch, both from the Department of Political and Social Change of the Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, for their advice and criticism in the preparation of this sub-thesis. I would also like to thank Dr Paul Real and Mr Geoffrey Jukes for their help in making my time at the Department of International Relations a knowledgeable one. I am also grateful to Brit Helgeby for all her help especially when I most needed it. 1 am most grateful to Philip Methven for his patience, advice and humour during the preparation of my thesis. Finally, 1 would like to thank my mother for all the support and encouragement that she has given me. Selena Gan Geok Hong, Canberra, June 1987. 3 Abbreviations AFP Armed Forces of the Philippines ASA Association of Southeast Asia ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations CG DK Coalition Government of Democratic -

Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Kampar Campus)

UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN (KAMPAR CAMPUS) FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION (HONS) PUBLIC RELATIONS UAMP3013 FINAL YEAR PROJECT II SEMESTER: JANUARY 2019 RESEARCH TITLE: MOTIVATIONS AND SATISFACTION: A STUDY ON YOUTUBE USE AMONG CHILDREN SUPERVISOR: MR CHIN YING SHIN INTERNAL EXAMINER: MR PONG KOK SHIONG G22 Name Student ID 1. LIEN KIM YEAN 1503483 2. LIEW SWET LI 1500907 3. WONG CHUN SIONG 1503296 4. YEE AN LI 1500677 5. YOON CHEE CONG 1504349 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, we would like to express our special appreciation to Mr Chin Ying Shin, our research supervisors. We would like to thank you for his valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this research work. Also, his patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work was greatly appreciated. Besides, we would like to extend our thanks to the headmasters of the two primary schools – Madam Lee Fong Foon, headmaster of SJK (C) Kampung Bali and En Hamdzan Bin Osman, headmaster of SK Methodist ACS Kampar. We would like to thank you for being welcoming for us to do the research work in the both primary schools. Moreover, we are deeply thankful to the respondents who were helped us to complete the questionnaires of this research work. Without them, we does not have the data for our research work. Last but not least, we would like to expand our gratitude to our family who encouraged and supported for us throughout the time of our research work. Thank you to those who have directly and indirectly helped us in this research work. -

Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions

NHBB A-Set Bee 2016-2017 Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions (1) A letter by Leonel Sharp provides this work's most widely accepted text, including the promises \you have deserved rewards and crowns" and \we shall shortly have a famous victory." In this speech, the speaker thinks \foul scorn that Parma or Spain [...] should dare to invade the borders of my realm" before promising to take up arms, despite having a \weak, feeble" body. For the point, name this 1588 speech delivered to an army awaiting the landing of the Spanish Armada by a leader who had the \heart and stomach of a King," Elizabeth I. ANSWER: Tilbury Speech (accept descriptions that use the name Tilbury; prompt on descriptions that don't, such as \Queen Elizabeth's speech to her army about the incoming Spanish Armada" or portions thereof, so long as the player includes something that the tossup hasn't gotten to yet) (2) This man represented holders of the Wentworth Grants in a New York court case; protecting his interests in those grants led this man and his family to form the Onion River Company. Late in life, this man published the deist book Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. After a meeting at Catamount Tavern, this man organized a militia group that went on to aid Benedict Arnold in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. For the point, name this man who advocated independence for Vermont and who led the Green Mountain Boys. ANSWER: Ethan Allen (3) This activity was re-affirmed to not be interstate commerce by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. -

Conference Schedule

ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT CONFERENCE ABSTRACT 2019 8th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science (ICBBS 2019) October 23-25, 2019 Grand Gongda Jianguo Hotel, Beijing, China Organized by Co-organized by Published and Indexed by http://www.icbbs.org/ ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT Table of Contents Introduction 4 Conference Committee 5~6 Program at-a-Glance 7~9 Presentation Instruction 10 Keynote Speaker Introduction 11~19 Invited Speaker Introduction 20~21 Oral Session on October 24, 2019 Session 1: Feature Extraction and Image Segmentation 22~26 Session 2: Pattern Recognition and Image Classification 27~31 Session 3: Medical Image Processing and Medical Testing 32~37 Session 4: Data Analysis and Soft Computing 38~42 Session 5: Target Detection 43~47 Session 6: Image Analysis and Signal Processing 48~53 Session 7: Molecular Biology and Biomedicine 54~59 Session 8: Computer Information Technology and Application 60~64 Poster Session on October 25, 2019 65~84 Conference Venue 85~86 Note 87~88 ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT Introduction Welcome to 2019 8th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science (ICBBS 2019) which is organized by Beijing University of Technology and Biology and Bioinformatics (BBS) under Hong Kong Chemical, Biological & Environmental Engineering Society (CBEES), co-organized by Tiangong University and Hebei University of Technology. The objective of ICBBS 2019 is to provide a platform for researchers, engineers, academicians as well as industrial professionals from all over the world to present their research results and development activities in Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science. Papers will be published in the following proceedings: ACM Conference Proceedings (ISBN: 978-1-4503-7251-0): archived in ACM Digital Library, indexed by EI Compendex and SCOPUS, and submitted to be reviewed by Thomson Reuters Conference Proceedings Citation Index (ISI Web of Science). -

Winds of Change in Sarawak Politics?

The RSIS Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. If you have any comments, please send them to the following email address: [email protected]. Unsubscribing If you no longer want to receive RSIS Working Papers, please click on “Unsubscribe.” to be removed from the list. No. 224 Winds of Change in Sarawak Politics? Faisal S Hazis S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 24 March 2011 About RSIS The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. RSIS’ mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia-Pacific. To accomplish this mission, RSIS will: Provide a rigorous professional graduate education in international affairs with a strong practical and area emphasis Conduct policy-relevant research in national security, defence and strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations Collaborate with like-minded schools of international affairs to form a global network of excellence Graduate Training in International Affairs RSIS offers an exacting graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. The teaching programme consists of the Master of Science (MSc) degrees in Strategic Studies, International Relations, International Political Economy and Asian Studies as well as The Nanyang MBA (International Studies) offered jointly with the Nanyang Business School. The graduate teaching is distinguished by their focus on the Asia-Pacific region, the professional practice of international affairs and the cultivation of academic depth. -

DOCURENT RESUME ED 134 108 HE 008 589 AUTHOR Kong

DOCURENT RESUME ED 134 108 HE 008 589 AUTHOR Kong, Kee Poo TITLE Tertiary Students and Social Development: An Area for Direct Action--Student Rural Service Activities in Malaysia. INSTITUTION Regional Inst. of Higher Education and Develdpment, Singapore. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 85p.; For related studies, see HE 008 588-590 AVAILABLE FROMRegional Institute of Higher Education and Development, CCSD1 Building, Hen Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore 5 ($6.00j EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Administrative Problems; Community Development; *Community Programs; *Developing Nations; Educational Finance; Enrollment Rate; Ethnic Distribution; *Higher Education; Public Support; Rural Areas; *Rural Development; School Community Relationship; *Student Volunteers; *Universities IDENTIFIERS Kebangsaan National University of Malaysia; *Malaysia; National Institute of Technology (Malaysia); Univeristy of Malaya; University of Agriculture (Malaysia); University of Science (Malaysia) ABSTRACT The study is a survey of the different kinds of voluntary rural service (service-learning) corps of students from the institutions ot higher-laducation in-ffaraysia. Tha-lattOry, organization, and activities of the service corps are examined, and this type of student social action is viewed with reference to the role of higher education in the social development of the country. Such student service activities are also considered in the wider perspective of other developing countries throughout the world, and an overview is given of the organizational, -

Civil Society and Democracy in Southeast Asia and Turkey

CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRACY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA TURKEY CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRACY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND TURKEY Edited by N. Ganesan Colin Dürkop ISBN: 978-605-4679-10-2 www.kas.de/tuerkei CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRACY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA AND TURKEY Edited by N. Ganesan Colin Dürkop Published by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of Konrad – Adenauer – Stiftung Ahmet Rasim Sokak No: 27 06550 Çankaya-Ankara/TÜRKİYE Telephone : +90 312 440 40 80 Faks : +90 312 440 32 48 E-mail : [email protected] www.kas.de/tuerkei ISBN : 978-605-4679-10-2 Designed & Printed by : OFSET FOTOMAT +90 312 395 37 38 Ankara, 2015 5 | ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 | INTRODUCTION 12 | CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRACY: TOWARDS A TAXONOMY Mark R. Thompson 44 | CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRATIC EVOLUTION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA N. Ganesan 67 | CIVIL SOCIETY, ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIA: THE CONTRADICTORY ROLE OF NON-STATE ACTORS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION Bob S. Hadiwinata and Christoph Schuck 96 | MALAYSIA: CROSS-COMMUNAL COALITION- BUILDING TO DENOUNCE POLITICAL VIOLENCE Chin-Huat Wong 129 | PHILIPPINE CIVIL SOCIETY AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN THE CONTEXT OF LEFT POLITICS Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem 160 | THAILAND’S DIVIDED CIVIL SOCIETY AT A TIME OF CRISIS Viengrat Nethipo 198 | LIFE AND TIMES OF CIVIL SOCIETY IN TURKEY: ISSUES, ACTORS, STRUCTURES Funda Gencoglu Onbasi 231 | CONCLUSION N. Ganesan 239 | NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book has been long in the making since the first workshop on state- society relations in Southeast Asia was first held in Kuala Lumpur in 2011.