DOCURENT RESUME ED 134 108 HE 008 589 AUTHOR Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

W W W . F E B . U N a I R . a C . I D

w w w . f e b . u n a i r . a c . i d FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA Campus B Jl. Airlangga 4, Surabaya - 60286, East Java - Indonesia Telephone : (+6231) 503 3642, 503 6584, 504 4940, 504 9480 Fax : (+6231) 502 6288 Email : [email protected] [email protected] www.feb.unair.ac.id THE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA - PROFILE THE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA - PROFILE 01 TABLE OF CONTENT 02 04 The Dean's Acknowledgement About Faculty of Economics and Business 06 08 Quality Recognition and Guarantee Faculty Leaders 10 12 Faculty of Economics and Business In Numbers Partnerships 14 15 Facilities Students' Awards 17 20 Department of Economics Department of Management 24 28 Department of Accounting Department of Islamic Economics 30 32 Research Institutions Scholarships and Admission THE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA - PROFILE 02 THE FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA - PROFILE 03 DEAN'S ACKNOWLEDGEMENT he Faculty of Economics and Business at Universitas Airlangga (FEB Unair) Twhich was founded in 1961 has had qualified experiences and capabilities in the field of education, researches, and social services especially in terms of economics and business. As one of the prominent faculties of economics in Indonesia, FEB Unair has been consistently determined to be an independent, innovative, and leading Faculty of Economics and Business both in national and international levels based on religious morality. In 2016, FEB Unair has been recorded to yield 1,075 graduates out of 10 study programs. In total, FEB Unair has had more than 25,000 alumni who have successfully become leading individuals, either in Prof. -

Chulalongkorn University Sustainability Report 2013-2014

Chulalongkorn University Sustainability Report 2013-2014 Based on ISCN-GULF Sustainable Campus Charter Contact Information Assoc.Prof. Boonchai Stitmannaithum, D.Eng. Vice President for Physical Resources Management Chulalongkorn University 254 Phaya Thai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330 THAILAND E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 02-218-3341 Table of Contents President's Statement 2 Introduction 6 About Chulalongkorn University 8 Sustainability at Chulalongkorn University 12 Principle 1 – Sustainability Performance of Buildings on Campus 15 Principle 2 – Campus-Wide Master Planning and Target Setting 23 Principle 3 – Integration of Facilities, Research and Education 32 Appendix A: Academic Programs with the Focus on Sustainability and Environment 36 Appendix B: Example of Courses with the Focus on Sustainability 37 Appendix C: Research Center and Initiatives on Sustainability and Environment 39 Appendix D: Related Activities, Projects and Programs on sustainability 42 Appendix E: Chemical Consumed by UN Class 2013-2014 44 Appendix F: Chulalongkorn University Chemical Waste Management Flow Chart 45 Appendix G: Faculty and Researcher Data 2013-2014 46 Appendix H: Student Data 2013-2014 47 President's Statement In recent years, "sustainability" has become the term whose meaning is critical to the development of Chulalongkorn University. From a segregated sustainable operation in the beginning stage that only focused on one operational area at one time, nowadays, Chulalongkorn University lays emphasis on an integrated sustainable operation concept which is not solely limited to energy and environment, but also to the understanding of interconnections between society, technology, culture, and the viability of future campus development. In 2014, many sustainable projects and programs were initiated. -

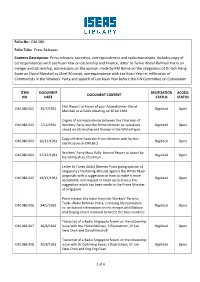

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

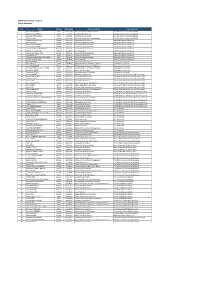

SHARE Scholarship - Batch 5 List of Awardees

SHARE Scholarship - Batch 5 List of Awardees No Name Gender Nationality Home university Host university 1 Thang CHERMENG Male Cambodia Royal University of Phnom Penh Bina Nusantara University (BINUS) 2 Vanhsay SILIPHOKHA Female Lao PDR Champasak University Bina Nusantara University (BINUS) 3 Souliyan KEOHAVONG Male Lao PDR Champasak University Bina Nusantara University (BINUS) 4 Yea Mouykea Female Cambodia National University of Management Bina Nusantara University (BINUS) 5 Khaing Yamoun KYAW Female Myanmar University of Mandalay Bogor Agricultural University 6 Ng YUEN MUN Female Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 7 Calley Debra YASING Female Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 8 Putri Naeila AMRAN Female Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 9 Cassandra Renee ANAK DAN Female Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 10 Nhi Thị Dao NGUYỄN Female Viet Nam Hue University Bogor Agricultural University 11 Lizzy Sheau Shiuan YAIK Female Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 12 Aung Khant OO Male Myanmar University of Yangon Bogor Agricultural University 13 Muhammad Izzat Safwan bin ABD Male Malaysia University Malaysia Sabah Bogor Agricultural University 14 Huyen Thị Ngọc MAI Female Viet Nam Hue University Bogor Agricultural University 15 Than Sin HTAIK Female Myanmar University of Mandalay Diponegoro University 16 Ngọc Hồng TA Male Viet Nam Vietnam National University, Hanoi Diponegoro University 17 Fatini -

CAMPUS Asia Program Overview FY2017 Budget: 650 Million Yen

CAMPUS Asia Program Overview FY2017 budget: 650 million yen CAMPUS Asia is a program that promotes quality-assured student exchanges through cooperation among the governments, quality assurance organizations, and universities of Japan, China, and Korea. From FY2011, ten pilot programs were selected through joint screening by the three countries and conducted. Since FY2016, in addition to eight programs that applied from among the ten pilot programs, nine new programs by the university consortium participating in CAMPUS Asia have been added for a total of 17 programs that have begun the full-fledged implementation of their activities. Record/plan of exchanges (no. of Japanese students sent abroad, foreign students received in Japan) - FY 2011-2015 (actual): Sent: 1,392, received: 1,485 - FY 2016-2020 (planned): Sent: 2,199; received: 2,076 Details At the 2nd Japan-China-Korea Summit in October 2009, Japan proposed, and agreement was reached on, trilateral high-quality inter- university exchanges. In April 2010, the trilateral 1st Experts Meeting was held in Tokyo (Japan side chairman: Yuichiro Anzai, President, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science). Agreement was reached on “CAMPUS Asia”* as the name for the program. *Stands for: “Collective Action for Mobility Program of University Students in Asia” In April 2015, at the 5th China-Japan-Korea Committee for Promoting Exchange and Cooperation among Universities, the three countries agreed that, with the end of the pilot program period, from FY2016, they would: 1) increase the number of trilateral inter- university collaboration programs, including the exchanges carried out as pilot programs, 2) make efforts to expand the collaborative framework of the Program (in the mid- and long-term) to the ASEAN countries. -

SHARE Scholarship Programme Awardees - Batch 2

SHARE Scholarship Programme Awardees - Batch 2 Student Country of No Awardee Name Gender Home University Study Programme Host University Number Citizenship 1 2-20160019 Amelia Yolanda Female Indonesia Bina Nusantara University Computer Science Taylor's University 2 2-20160032 Metta Handika Female Indonesia Bina Nusantara University Mobile Application and Technology Taylor's University 3 2-20160067 Muhammad Dwiki Hermawan Male Indonesia Bina Nusantara University Industrial Engineering and Information Systems Hanoi University of Science and Technology 4 2-20160105 Yvonne Michelle Chen Female Indonesia Bina Nusantara University Computer Science University of Cambodia 5 2-20160033 Fernando Male Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Fisheries and Marine Science Viet Nam National University, Ha Noi 6 2-20160042 Fera Wahyuni Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Agribusiness Payap University 7 2-20160081 Nur Aini Lukitasari Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Resources and Environmental Economics University of Cambodia 8 2-20160083 Reffi Dewi Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Resources and Environmental Economics University of Cambodia 9 2-20160144 Vindy Dwi Paramitha Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Agribusiness University of Santo Tomas 10 2-20160157 Yanti Octaviani Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Resources and Environmental Economics Hue University 11 2-20160162 Maulida Nurul Fatkhiyatut Taufiqoh Female Indonesia Bogor Agricultural University Management Hue University 12 2-20160241 -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

JSS 075 0A Front

JOURNAL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY 1987 VOLUME 75 THE SIAM SOCIETY PATRON His Majesty the King VICE-PATRONS Her Majesty th e Queen Her Royal Highness the Princess Mother Her Royal Highn ess Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn HON. PRESIDENT Her Royal Highness Princess Galyani Vadhana HON . VICE~PRESIDENTS Mr. Alexander B. G riswold Mom Kobkaew Abhakara Na Ayudhaya H .S.H. Prince Subhadradis Disk ul HON. MEMBERS The Yen. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu The Yen. Phra Rajavaramuni (Payutto) Mr. Fua Haripitak Dr. Mary R . Haas Dr. Puey Ungphakorn Soedjatmoko Dr. Sood Saengvichien H.S .H. Prince Chand Chirayu Rajani Professor William J . Gedney Professor Prawase Wasi M.D. HON. AUDITOR Mr. Yukta na Thalang HON . ARCHITECT Mr. Sirichai Narumit COUNCIL OF THE SIAM SOCIETY FOR 1987/88 M.R. Patanachai Jayant President Dr. Tern Smitinand Vice President Mr. Dacre F.A. Raikes Vice President Mrs. Katherine Buri Vice President & Honorary Treasurer Mrs. Virginia M. Di Crocco Honorary Secretary Mr. Jitkasem Sangsingkeo Honorary Librarian Mr. Sulak Sivaraksa / Honorary Editor of the JSS Dr. Rachit Buri ;y Honorary Leader of the Natural History Section Dr. Warren Brockelman .,. Honorary Editor of the NHB Mr. James Stent Honorary Officer (Asst. Honorary Treasurer) Mrs. Bonnie Davis -? Honorary Officer (Asst. Honorary Librarian) Mrs. Yarasee Rattakunjara Honorary Officer (Asst. Honorary Secretary) M.R . Narisa Chakrabongse ?' Honorary Officer (Associate Editor of the JSS) Mrs. Juliette Muscat Honorary Officer (for Special Project) Mrs. Nongyao Narumit -:J' Honorary Officer (for Public Relations) Dr. Paul P. Blackburn Dr. Thawatchai Santisuk Dr. Chak Dhanasiri Mr. Hartmut W. Schneider ' Mr. Patt Djaratbhart (P.R .N. -

Factors Influencing Purchase Intention Towards Dietary Supplement Products Among Young

Running head: FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 1 Factors Influencing Purchase Intention towards Dietary Supplement Products among Young Adults Lee Jia Hou, Lim Kwoh Fronn, and Yong Kai Yun Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 2 Abstract This study aimed to explore the factors affecting young adults‟ purchase intention towards dietary supplement products. These factors included attitude towards consuming dietary supplements, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, as well as demographic characteristics such as gender, income, and residential area. 300 respondents were equally recruited from the internet and also UTAR, Kampar campus to complete the questionnaire. Findings concluded that perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude significantly predicted the purchase intention of dietary supplement products. Among these variables, subjective norms was the strongest predictor. Besides that, demographic characteristic such as gender difference was found significant in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. In contrast, there was no significant difference found between types of residential area in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. A significant and positive relationship between income and purchase intention was discovered. The findings strengthened the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of predicting purchase intention of dietary supplement products among young adults. Subjective norms, being the most significant predictor of purchase intention could also be constructive for marketers to effectively publicize dietary supplement use. Keywords: young adults, purchase intention, dietary supplement products, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background of study Health care related issues, ranging from increasing rates of chronic diseases, reduced life expectancy and growing health care expenses are common globally. -

Attachment As a Predictor of University Adjustment Among Freshmen: Evidence from a Malaysian Public University

Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 111 ATTACHMENT AS A PREDICTOR OF UNIVERSITY ADJUSTMENT AMONG FRESHMEN: EVIDENCE FROM A MALAYSIAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY 1Walton Wider, 2Mazni Mustapha, 3Murnizam Halik & 4Ferlis Bahari 1Faculty of Arts and Social Science Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia 2-3Faculty of Psychology and Education Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 4Psychology and Social Health Research Unit Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 1Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Purpose – Building upon attachment theory and emerging theory, the current study was aimed at examining the effect of peer attachment in predicting adjustment to life in university among freshmen in a public unirvsity in East Malaysia. Furthermore, it sought to examine the influence of gender and perceived-adult status as moderators of the relationship between student attachment and student adjustment. Methodology – Data was collected from 557 freshmen in one of the public universities in East Malaysia. Two questionnaires, namely The Inventory of Parent and Peers Attachment (IPPA) and The Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ) were used in this study. Partial Least Square (PLS) analysis was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships. Findings – The findings of the study showed that peer trust positively influenced academic and social adjustment. Meanwhile, peer communication positively influenced social adjustment, but negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment. Lastly, peer alienation negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment, but positively influenced institutional attachment. The Partial Least 112 Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 Square - Multi Group Analysis (PLS-MGA) results indicated no significant differences in peer attachment and university adjustment across gender and perceived-adult status. -

Malaysian Parliament 1965

Official Background Guide Malaysian Parliament 1965 Model United Nations at Chapel Hill XVIII February 22 – 25, 2018 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director ………………………………………………………………… 3 Letter from the Chair ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Background Information ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Background: Singapore ……………………………………………………… 5 Background: Malaysia ……………………………………………………… 9 Identity Politics ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Radical Political Parties ………………………………………………………………………… 14 Race Riots ……………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Positions List …………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Endnotes ……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Parliament of Malaysia 1965 Page 2 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Malaysian Parliament of 1965 Committee at the Model United Nations at Chapel Hill 2018 Conference! My name is Annah Bachman and I have the honor of serving as your Crisis Director. I am a third year Political Science and Philosophy double major here at UNC-Chapel Hill and have been involved with MUNCH since my freshman year. I’ve previously served as a staffer for the Democratic National Committee and as the Crisis Director for the Security Council for past MUNCH conferences. This past fall semester I studied at the National University of Singapore where my idea of the Malaysian Parliament in 1965 was formed. Through my experience of living in Singapore for a semester and studying its foreign policy, it has been fascinating to see how the “traumatic” separation of Singapore has influenced its current policies and relations with its surrounding countries. Our committee is going back in time to just before Singapore’s separation from the Malaysian peninsula to see how ethnic and racial tensions, trade policies, and good old fashioned diplomacy will unfold. Delegates should keep in mind that there is a difference between Southeast Asian diplomacy and traditional Western diplomacy (hint: think “ASEAN way”). -

USYD Global Mobility Guide

2020 edition Global Mobility Guide Global MobilityGlobal Guide 2020 edition Why study overseas? �������������������������������������� 2 Our global mobility programs �����������������������4 Getting credit towards your course �������������9 How to apply �������������������������������������������������� 10 Our Super Exchange Partners ���������������������14 Where can I study? ����������������������������������������16 Scholarships and costs ��������������������������������22 Global Citizenship Award�����������������������������26 What’s next? ��������������������������������������������������28 #usydontour FAQs �����������������������������������������������������������������31 “Just two words: DO IT. I have not met one person who has regretted their overseas experience. It is simply not possible to live/ study overseas without gaining something out Why study overseas? of it. Whether it is new friends or important lessons learned. Usually both! Living and studying overseas is a once in a lifetime The University of Sydney has the largest global student opportunity that will change you for the better.” mobility program in Australia*� Combine study and travel to Yasmin Dowla Bachelor of Arts/Bachelor of Economics broaden your academic experience and set yourself up for University of Edinburgh, Scotland a global career� Develop the cultural competencies to work across borders, while having the experience of a lifetime� sydney.edu.au/study/overseas-programs Develop your Experience new self-confidence, ways of learning Gain a Over independence