The Influence of Budi-Islam Values on Tunku Abdul Rahman (Tunku) Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

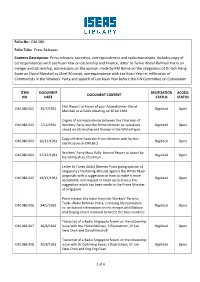

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Coral Reefs in the Coastal Waters of the South China Sea MALAYSIA Mr. Abdul Rahim Bin Gor Yaman Focal Point for Coral Reefs Marine Park Section, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Level 11, Lot 4G3, Precinct 4, Federal Government Administrative Centre 62574 Putrajaya, Selangor, Malaysia NATIONAL REPORT ON CORAL REEF IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – MALAYSIA 37 MALAYSIA Zahaitun Mahani Zakariah, Ainul Raihan Ahmad, Tan Kim Hooi, Mohd Nisam Barison and Nor Azlan Yusoff Maritime Institute of Malaysia INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s coral reefs extend from the renowned “Coral Triangle” connecting it with Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. Coral reef types in Malaysia are mostly shallow fringing reefs adjacent to the offshore islands. The rest are small patch reefs, atolls and barrier reefs. The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Atlas of Coral Reefs prepared by the Coral Reef Unit, estimated the size of Malaysia’s coral reef area at 3,600sq. km which is 1.27 percent of world total coverage (Spalding et al., 2001). Coral reefs support an abundance of economically important coral fishes including groupers, parrotfishes, rabbit fishes, snappers and fusiliers. Coral fish species from Serranidae, Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae contributed between 10 to 30 percent of marine catch in Malaysia (Wan Portiah, 1990). In Sabah, coral reefs support artisanal fisheries but are adversely affected by unsustainable fishing practices, including bombing and cyanide fishing. Almost 30 percent of Sabah’s marine fish catch comes from coral reef areas (Department of Fisheries Sabah, 1997). -

Factors Influencing Purchase Intention Towards Dietary Supplement Products Among Young

Running head: FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 1 Factors Influencing Purchase Intention towards Dietary Supplement Products among Young Adults Lee Jia Hou, Lim Kwoh Fronn, and Yong Kai Yun Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 2 Abstract This study aimed to explore the factors affecting young adults‟ purchase intention towards dietary supplement products. These factors included attitude towards consuming dietary supplements, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, as well as demographic characteristics such as gender, income, and residential area. 300 respondents were equally recruited from the internet and also UTAR, Kampar campus to complete the questionnaire. Findings concluded that perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitude significantly predicted the purchase intention of dietary supplement products. Among these variables, subjective norms was the strongest predictor. Besides that, demographic characteristic such as gender difference was found significant in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. In contrast, there was no significant difference found between types of residential area in purchase intention of dietary supplement products. A significant and positive relationship between income and purchase intention was discovered. The findings strengthened the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) of predicting purchase intention of dietary supplement products among young adults. Subjective norms, being the most significant predictor of purchase intention could also be constructive for marketers to effectively publicize dietary supplement use. Keywords: young adults, purchase intention, dietary supplement products, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control FACTORS INFLUENCING PURCHASE INTENTION 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Background of study Health care related issues, ranging from increasing rates of chronic diseases, reduced life expectancy and growing health care expenses are common globally. -

Attachment As a Predictor of University Adjustment Among Freshmen: Evidence from a Malaysian Public University

Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 111 ATTACHMENT AS A PREDICTOR OF UNIVERSITY ADJUSTMENT AMONG FRESHMEN: EVIDENCE FROM A MALAYSIAN PUBLIC UNIVERSITY 1Walton Wider, 2Mazni Mustapha, 3Murnizam Halik & 4Ferlis Bahari 1Faculty of Arts and Social Science Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia 2-3Faculty of Psychology and Education Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 4Psychology and Social Health Research Unit Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia 1Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Purpose – Building upon attachment theory and emerging theory, the current study was aimed at examining the effect of peer attachment in predicting adjustment to life in university among freshmen in a public unirvsity in East Malaysia. Furthermore, it sought to examine the influence of gender and perceived-adult status as moderators of the relationship between student attachment and student adjustment. Methodology – Data was collected from 557 freshmen in one of the public universities in East Malaysia. Two questionnaires, namely The Inventory of Parent and Peers Attachment (IPPA) and The Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ) were used in this study. Partial Least Square (PLS) analysis was employed to examine the hypothesized relationships. Findings – The findings of the study showed that peer trust positively influenced academic and social adjustment. Meanwhile, peer communication positively influenced social adjustment, but negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment. Lastly, peer alienation negatively influenced personal-emotional adjustment, but positively influenced institutional attachment. The Partial Least 112 Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction: Vol. 14 No. 1 (2017): 111-144 Square - Multi Group Analysis (PLS-MGA) results indicated no significant differences in peer attachment and university adjustment across gender and perceived-adult status. -

Malaysian Parliament 1965

Official Background Guide Malaysian Parliament 1965 Model United Nations at Chapel Hill XVIII February 22 – 25, 2018 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director ………………………………………………………………… 3 Letter from the Chair ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Background Information ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Background: Singapore ……………………………………………………… 5 Background: Malaysia ……………………………………………………… 9 Identity Politics ………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Radical Political Parties ………………………………………………………………………… 14 Race Riots ……………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Positions List …………………………………………………………………………………… 18 Endnotes ……………………………………………………………………………………… 22 Parliament of Malaysia 1965 Page 2 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to the Malaysian Parliament of 1965 Committee at the Model United Nations at Chapel Hill 2018 Conference! My name is Annah Bachman and I have the honor of serving as your Crisis Director. I am a third year Political Science and Philosophy double major here at UNC-Chapel Hill and have been involved with MUNCH since my freshman year. I’ve previously served as a staffer for the Democratic National Committee and as the Crisis Director for the Security Council for past MUNCH conferences. This past fall semester I studied at the National University of Singapore where my idea of the Malaysian Parliament in 1965 was formed. Through my experience of living in Singapore for a semester and studying its foreign policy, it has been fascinating to see how the “traumatic” separation of Singapore has influenced its current policies and relations with its surrounding countries. Our committee is going back in time to just before Singapore’s separation from the Malaysian peninsula to see how ethnic and racial tensions, trade policies, and good old fashioned diplomacy will unfold. Delegates should keep in mind that there is a difference between Southeast Asian diplomacy and traditional Western diplomacy (hint: think “ASEAN way”). -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools MACAU 001199 Univ Asia

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools MACAU 001199 Univ Asia Oriental 001199 Univ East Asia 001199 University Of Macau MADAGASCAR 003655 Gim Koco Racin 003655 Koco Racin Gymnasium 000228 Univ Bitola 000239 Univ Kiril Metodij Skopju 001190 Univ Madagascar 000239 Univ Skopje 001190 University Of Madagascar 000228 Univerzitet Bitola MALAWI 000747 Bunda Col Agri 000747 Chancellor Col 000747 Kamuzu Col Nursing 005074 Malamulo School 000747 Pol Blantyre 000747 Univ Malawi MALAYSIA 004835 Alam Shah 004820 Assunta Secondary Sch 004333 Bbgs Seconary School 004154 Bukit Mertajam High School 004836 Clifford Secondary School 000748 Col Agri Malaya 004315 College Damansara Utama 003358 Damansara Jaya Sec School 004340 Datuk Abdul Razak School 003871 Disted College 004656 Federal Islamic Hs 003586 Higher Education Learn Progamm 002083 Inst Tech Mara 002083 Inst Teknologi Mara 002083 Institut Teknologi Mara 002083 Itm 003088 Jalan Mengkibol High School 004838 Johore Science Secondary 004315 Kolej Damansara Utama 003871 Kolej Disted 004338 Kolej Tunku Kurshiah 004438 La Salle School 004151 Maktab Rendah Sains Mara Serti 004341 Malacca High School 003423 Mara Community College 002083 Mara Inst Tech 003448 Mara Jr Science College Bantin 005128 Mara Junior College 004334 Mara Junior Science College International Schools 004349 Methodist Secondary School 004331 Muar Science Secondary Sch 004339 Muslim College Klang 000750 Na Univ Malaysia 000751 Northern Univ Malaysia 004971 Petaling Garden Girls Sec Sch 004331 Science Secondary School 004332 Science Selangor -

Parliamentary Debates

Volume III Tuesday No. 41 30 January, 1962 ~J*\ PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RA'AYAT (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES) OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENTS EXEMPTED BUSINESS (MOTION) [Col. 4320] BILL- The Constitution (Amendment) Bill (continuation) [Col. 4269] OI~TERBITKAN OLER THOR BENG CHONG, A.M.N., PEMANGKU PENCHETAIC ICEIVJAAN PERSEKlM'UAN TANAH MELA.YU 1962 Harga: $1 FEDERATION OF MALAYA DEWAN RA'AYAT (HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES) Official Report Third Session of the First Dewan Ra'ayat Tuesday, 30th January, 1962 The House met at Ten o'clock a.m. PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. Speaker, DATO' HAJI MOHAMED NOAH BIN OMAR, S.P.M.J., D.P.M.B., P.I.S., J.P. the Prime Minister and Minister of External Affairs, Y.T.M. TuNKU ABDUL RAHMAN PuTRA AL-HAJ, K.O.M. (Kuala Kedah). the Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Defence and Minister of Rural Development, TuN HAn ABDUL RAZAK BIN DATO' HUSSAIN, S.M.N. (Pekan). the Minister of Internal Security and Minister of the Interior. DATO' DR. ISMAIL BIN DATO' HAJI ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N. (Johor Timor). the Minister of Finance, ENCHE' TAN Srnw SIN. J.P. (Melaka Tengah). the Minister of Works, Posts and Telecommunications, DATO' v. T. SAMBANTHAN, P.M.N. (Sungai Siput). the Minister without Portfolio, DATO' SULEIMAN BIN DATO' HAJI ABDUL RAHMAN, P.M.N. (Muar Selatan). the Minister of Transport, DATO' SARDON BIN HAJI JuBIR, P.M.N. (Pontian Utara). the Minister of Commerce and Industry, ENCHE' MOHAMED KHIR mN JoHARI (Kedah Tengah). the Minister of Labour, ENcHE' BAHAMAN BlN SAMSUDIN (Kuala Pilah). the Minister of Education, ENCHE' ABDUL RAHMAN BIN HAJI TALIB (Kuantan). -

Text and Screen Representations of Puteri Gunung Ledang

‘The legend you thought you knew’: text and screen representations of Puteri Gunung Ledang Mulaika Hijjas Abstract: This article traces the evolution of narratives about the supernatural woman said to live on Gunung Ledang, from oral folk- View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE lore to sixteenth-century courtly texts to contemporary films. In provided by SOAS Research Online all her instantiations, the figure of Puteri Gunung Ledang can be interpreted in relation to the legitimation of the state, with the folk- lore preserving her most archaic incarnation as a chthonic deity essential to the maintenance of the ruling dynasty. By the time of the Sejarah Melayu and Hikayat Hang Tuah, two of the most impor- tant classical texts of Malay literature, the myth of Puteri Gunung Ledang had been desacralized. Nevertheless, a vestigial sense of her importance to the sultanate of Melaka remains. The first Malaysian film that takes her as its subject, Puteri Gunung Ledang (S. Roomai Noor, 1961), is remarkably faithful to the style and sub- stance of the traditional texts, even as it reworks the political message to suit its own time. The second film, Puteri Gunung Ledang (Saw Teong Hin, 2004), again exemplifies the ideology of its era, depoliticizing the source material even as it purveys Barisan Nasional ideology. Keywords: myth; invention of tradition; Malay literature; Malaysian cinema Author details: Mulaika Hijjas is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fel- low in the Department of South East Asia, SOAS, Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. -

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: the Fall of Marcos

ASEAN-Philippine Relations: The Fall of Marcos Selena Gan Geok Hong A sub-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Relations) in the Department of International Relations, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra. June 1987 1 1 certify that this sub-thesis is my own original work and that all sources used have been acknowledged Selena Gan Geok Hong 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 Chapter One 14 Chapter Two 33 Chapter Three 47 Conclusion 62 Bibliography 68 2 Acknowledgements 1 would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Ron May and Dr Harold Crouch, both from the Department of Political and Social Change of the Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, for their advice and criticism in the preparation of this sub-thesis. I would also like to thank Dr Paul Real and Mr Geoffrey Jukes for their help in making my time at the Department of International Relations a knowledgeable one. I am also grateful to Brit Helgeby for all her help especially when I most needed it. 1 am most grateful to Philip Methven for his patience, advice and humour during the preparation of my thesis. Finally, 1 would like to thank my mother for all the support and encouragement that she has given me. Selena Gan Geok Hong, Canberra, June 1987. 3 Abbreviations AFP Armed Forces of the Philippines ASA Association of Southeast Asia ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations CG DK Coalition Government of Democratic -

Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (Kampar Campus)

UNIVERSITI TUNKU ABDUL RAHMAN (KAMPAR CAMPUS) FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION (HONS) PUBLIC RELATIONS UAMP3013 FINAL YEAR PROJECT II SEMESTER: JANUARY 2019 RESEARCH TITLE: MOTIVATIONS AND SATISFACTION: A STUDY ON YOUTUBE USE AMONG CHILDREN SUPERVISOR: MR CHIN YING SHIN INTERNAL EXAMINER: MR PONG KOK SHIONG G22 Name Student ID 1. LIEN KIM YEAN 1503483 2. LIEW SWET LI 1500907 3. WONG CHUN SIONG 1503296 4. YEE AN LI 1500677 5. YOON CHEE CONG 1504349 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, we would like to express our special appreciation to Mr Chin Ying Shin, our research supervisors. We would like to thank you for his valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and development of this research work. Also, his patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work was greatly appreciated. Besides, we would like to extend our thanks to the headmasters of the two primary schools – Madam Lee Fong Foon, headmaster of SJK (C) Kampung Bali and En Hamdzan Bin Osman, headmaster of SK Methodist ACS Kampar. We would like to thank you for being welcoming for us to do the research work in the both primary schools. Moreover, we are deeply thankful to the respondents who were helped us to complete the questionnaires of this research work. Without them, we does not have the data for our research work. Last but not least, we would like to expand our gratitude to our family who encouraged and supported for us throughout the time of our research work. Thank you to those who have directly and indirectly helped us in this research work. -

Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions

NHBB A-Set Bee 2016-2017 Bee Final Round Bee Final Round Regulation Questions (1) A letter by Leonel Sharp provides this work's most widely accepted text, including the promises \you have deserved rewards and crowns" and \we shall shortly have a famous victory." In this speech, the speaker thinks \foul scorn that Parma or Spain [...] should dare to invade the borders of my realm" before promising to take up arms, despite having a \weak, feeble" body. For the point, name this 1588 speech delivered to an army awaiting the landing of the Spanish Armada by a leader who had the \heart and stomach of a King," Elizabeth I. ANSWER: Tilbury Speech (accept descriptions that use the name Tilbury; prompt on descriptions that don't, such as \Queen Elizabeth's speech to her army about the incoming Spanish Armada" or portions thereof, so long as the player includes something that the tossup hasn't gotten to yet) (2) This man represented holders of the Wentworth Grants in a New York court case; protecting his interests in those grants led this man and his family to form the Onion River Company. Late in life, this man published the deist book Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. After a meeting at Catamount Tavern, this man organized a militia group that went on to aid Benedict Arnold in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga. For the point, name this man who advocated independence for Vermont and who led the Green Mountain Boys. ANSWER: Ethan Allen (3) This activity was re-affirmed to not be interstate commerce by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. -

Education and Nation-Building in Plural Societies: the West Malaysian Experience

The Ausrrolion Development Studies Centre Norionol Universiry Monograph no. 6 Education and nation-buildingin plural societies: The West Malaysian experience The Development Studies Centre has been set up within the Australian National University to help foster and co-ordinate development studies within the University and with other Institutions. The work of the Centre is guided by an Executive Committee under the chairmanship of the Vice Chancellor. The Deputy Chairman is the Director of the Research School of Pacific Studies. The other members of the Committee are: Professor H.W. Arndt Dr W. Kasper Dr C. Barlow Professor D.A. Low Professor J.C. Caldwell (Chairman) Mr E.C. Chapman Dr T .G. McGee Dr R.K. Darroch Dr R.C. Manning Dr C.T. Edwards Dr R.J. May Mr E.K. Fisk Mr D. Mentz Professor J. Fox Dr S.S. Richardson Mr J.L. Goldring Dr L. T. Ruzicka Professor D.M. Griffin Professor T.H. Silcock Mr D.O. Hay Dr R.M. Sundrum Mr J. Ingram Professor Wang Gungwu Professor B.LC. Johnson (Dep. Chairm�n) Dr G.W. Jones Professor R.G. Ward Development Studies Centre Monograph no. 6 Education and nation-building in plural societies: The West Malaysian experience Chai Hon-Chan Series editor E.K Fisl� The Australian National University Canberra 1977 © Chai Hon-Chan 1977 This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries may be made to the publisher.