Cardinal Jaime Sin Instrumental in the People’S Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of Virata's Network: Technocracy and the Politics Of

The Rise and Fall of Virata’s Network: Technocracy and the Politics of Economic Decision Making in the Philippines Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem* The influence of a technocratic network in the Philippines that was formed around Cesar E. A. Virata, prime minister under Ferdinand Marcos, rose during the martial law period (1972–86), when technocracy was pushed to the forefront of economic policy making. Applying concepts of networks, this essay traces the rise and even- tual collapse of Virata’s network to a three-dimensional interplay of relationships— between Virata and Marcos, Virata and the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, and Marcos and the United States. Virata’s close links to social, academic, US, and business community networks initially thrust him into government, where he shared Marcos’s goal of attracting foreign investments to build an export-oriented economy. Charged with obtaining IMF and World Bank loans, Virata’s network was closely joined to Marcos as the principal political hub. Virata, however, had to contend with the networks of Marcos’s wife, Imelda, and the president’s “chief cronies.” While IMF and World Bank support offered Virata some leverage, his network could not control Imelda Marcos’s profligacy or the cronies’ sugar and coconut monopolies. In Virata’s own assessment, his network was weakened when Marcos’s health failed during an economic crisis in 1981 and after Benigno Aquino’s assassination in 1983. In those crises, Imelda Marcos’s network and Armed Forces Chief of Staff General Fabian Ver’s faction of the military network took power amidst the rise of an anti-dictatorship movement. -

The Catholic Church and the Reproductive Health Bill Debate: the Philippine Experience

bs_bs_banner HeyJ LV (2014), pp. 1044–1055 THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH BILL DEBATE: THE PHILIPPINE EXPERIENCE ERIC MARCELO O. GENILO, SJ Loyola School of Theology, Philippines The leadership of the Church in the Philippines has historically exercised a powerful influence on politics and social life. The country is at least 80% Catholic and there is a deeply ingrained cultural deference for clergy and religious. Previous attempts in the last 14 years to pass a reproductive health law have failed because of the opposition of Catholic bishops. Thus the recent passage of the ‘Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012’ (R.A. 10354) was viewed by some Filipinos as a stunning failure for the Church and a sign of its diminished influence on Philippine society. This article proposes that the Church’s engagement in the reproductive health bill (RH Bill) debate and the manner of its discourse undermined its own campaign to block the law.1 The first part of the article gives a historical overview of the Church’s opposition to government family planning programs. The second part discusses key points of conflict in the RH Bill debate. The third part will examine factors that shaped the Church’s attitude and responses to the RH Bill. The fourth part will examine the effects of the debate on the Church’s unity, moral authority, and role in Philippine society. The fifth part will draw lessons for the Church and will explore paths that the Church community can take in response to the challenges arising from the law’s implementation. -

The 1986 EDSA Revolution? These Are Just Some of the Questions That You Will Be Able to Answer As You Study This Module

What Is This Module About? “The people united will never be defeated.” The statement above is about “people power.” It means that if people are united, they can overcome whatever challenges lie ahead of them. The Filipinos have proven this during a historic event that won the admiration of the whole world—the 1986 EDSA “People Power” Revolution. What is the significance of this EDSA Revolution? Why did it happen? If revolution implies a struggle for change, was there any change after the 1986 EDSA Revolution? These are just some of the questions that you will be able to answer as you study this module. This module has three lessons: Lesson 1 – Revisiting the Historical Roots of the 1986 EDSA Revolution Lesson 2 – The Ouster of the Dictator Lesson 3 – The People United Will Never Be Defeated What Will You Learn From This Module? After studying this module, you should be able to: ♦ identify the reasons why the 1986 EDSA Revolution occurred; ♦ describe how the 1986 EDSA Revolution took place; and ♦ identify and explain the lessons that can be drawn from the 1986 EDSA Revolution. 1 Let’s See What You Already Know Before you start studying this module, take this simple test first to find out what you already know about this topic. Read each sentence below. If you agree with what it says, put a check mark (4) under the column marked Agree. If you disagree with what it says, put a check under the Disagree column. And if you’re not sure about your answer, put a check under the Not Sure column. -

Current Bus Service Operating Characteristics Along EDSA, Metro Manila

TSSP 22 nd Annual Conference of the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines Iloilo City, Philippines, 12 Sept 2014 2014 Current Bus Service Operating Characteristics Along EDSA, Metro Manila Krister Ian Daniel Z. ROQUEL Alexis M. FILLONE, Ph.D. Research Specialist Associate Professor Civil Engineering Department Civil Engineering Department De La Salle University - Manila De La Salle University - Manila 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA) has been the focal point of many transportation studies over the past decade, aiming towards the improvement of traffic conditions across Metro Manila. Countless researches have tested, suggested and reviewed proposed improvements on the traffic condition. This paper focuses on investigating the overall effects of the operational and administrative changes in the study area over the past couple of years, from the full system operation of the Mass Rail Transit (MRT) in the year 2000 to the present (2014), to the service operating characteristics of buses plying the EDSA route. It was found that there are no significant changes in the average travel and running speeds for buses running Southbound, while there is a noticeable improvement for those going Northbound. As for passenger-kilometers carried, only minor changes were found. The journey time composition percentages did not show significant changes over the two time frames as well. For the factors contributing to passenger-related time, the presence of air-conditioning and the direction of travel were found to contribute as well, aside from the number of embarking and/or disembarking passengers and number of standing passengers. -

Transportation History of the Philippines

Transportation history of the Philippines This article describes the various forms of transportation in the Philippines. Despite the physical barriers that can hamper overall transport development in the country, the Philippines has found ways to create and integrate an extensive transportation system that connects the over 7,000 islands that surround the archipelago, and it has shown that through the Filipinos' ingenuity and creativity, they have created several transport forms that are unique to the country. Contents • 1 Land transportation o 1.1 Road System 1.1.1 Main highways 1.1.2 Expressways o 1.2 Mass Transit 1.2.1 Bus Companies 1.2.2 Within Metro Manila 1.2.3 Provincial 1.2.4 Jeepney 1.2.5 Railways 1.2.6 Other Forms of Mass Transit • 2 Water transportation o 2.1 Ports and harbors o 2.2 River ferries o 2.3 Shipping companies • 3 Air transportation o 3.1 International gateways o 3.2 Local airlines • 4 History o 4.1 1940s 4.1.1 Vehicles 4.1.2 Railways 4.1.3 Roads • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 External links Land transportation Road System The Philippines has 199,950 kilometers (124,249 miles) of roads, of which 39,590 kilometers (24,601 miles) are paved. As of 2004, the total length of the non-toll road network was reported to be 202,860 km, with the following breakdown according to type: • National roads - 15% • Provincial roads - 13% • City and municipal roads - 12% • Barangay (barrio) roads - 60% Road classification is based primarily on administrative responsibilities (with the exception of barangays), i.e., which level of government built and funded the roads. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Naming the Artist, Composing the Philippines: Listening for the Nation in the National Artist Award A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Neal D. Matherne June 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Sally Ann Ness Dr. Jonathan Ritter Dr. Christina Schwenkel Copyright by Neal D. Matherne 2014 The Dissertation of Neal D. Matherne is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This work is the result of four years spent in two countries (the U.S. and the Philippines). A small army of people believed in this project and I am eternally grateful. Thank you to my committee members: Rene Lysloff, Sally Ness, Jonathan Ritter, Christina Schwenkel. It is an honor to receive your expert commentary on my research. And to my mentor and chair, Deborah Wong: although we may see this dissertation as the end of a long journey together, I will forever benefit from your words and your example. You taught me that a scholar is not simply an expert, but a responsible citizen of the university, the community, the nation, and the world. I am truly grateful for your time, patience, and efforts during the application, research, and writing phases of this work. This dissertation would not have been possible without a year-long research grant (2011-2012) from the IIE Graduate Fellowship for International Study with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I was one of eighty fortunate scholars who received this fellowship after the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Program was cancelled by the U.S. -

JEEP Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

JEEP bus time schedule & line map JEEP EDSA/Shaw Central - Kalentong/JRC View In Website Mode The JEEP bus line (EDSA/Shaw Central - Kalentong/JRC) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila →Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM (2) Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila →Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest JEEP bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next JEEP bus arriving. Direction: Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw JEEP bus Time Schedule Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw Blvd Manila →Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila →Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila Route Timetable: 10 stops VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, Philippines Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Philippine Cosmetic And Plastic Surgery, Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Friday 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Asi Automation & Security Innovation Products & Services, Shaw Blvd., Mandaluyong City, Manila Saturday 12:00 AM - 10:00 PM S. Laurel / Shaw Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila JEEP bus Info Direction: Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / Shaw Shaw Blvd / Luna Mencias Intersection, Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila →Shaw Mandaluyong City, Manila Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila 397 Shaw Boulevard, Philippines Stops: 10 Trip Duration: 16 min Shaw Blvd / Acacia Ln Intersection, Mandaluyong Line Summary: Epifanio De Los Santos Avenue / City Shaw Blvd Intersection, Mandaluyong City, Manila, 321 Shaw Boulevard, Philippines Philippine Cosmetic And Plastic Surgery, Shaw Blvd, Mandaluyong City, Manila, Asi Automation & Security L. -

Malacañang Says China Missiles Deployed in Disputed Seas Do Not

Warriors move on to face Rockets in West WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE SPORTS NEWS | A5 Vol. IX Issue 474 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Email: [email protected] Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 May 10 - 16, 2018 White House, some PH solons oppose China installing missiles Malacañang says China missiles deployed in Spratly By Macon Araneta in disputed seas do not target PH FilAm Star Correspondent By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent Malacañang’s reaction to the expressions of concern over the recent Chinese deploy- ment of missiles in the Spratly islands is one of nonchalance supposedly because Beijing said it would not use these against the Philippines and that China is a better source of assistance than America. Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said the improving ties between the Philippines and U.S. Press Sec. Sarah Sanders China is assurance enough that China will not use (Photo: www.newsx.com) its missiles against the Philippines. This echoed President Duterte’s earlier remarks when security The White House warned that China would experts warned that China’s installation of mis- face “consequences” for their leaders militarizing siles in the Spratly islands threatens the Philip- the illegally-reclaimed islands in the West Philip- pines’ international access in the disputed South pine Sea (WPS). China Sea. The installation of Chinese missiles were Duterte said China has not asked for any- reported on Fiery Reef, Subi Reef and Mischief thing in return for its assistance to the Philip- Reef in the Spratly archipelago that Manila claims pines as he allayed concerns of some groups over as its territory. -

The Filipino Ringside Community: National Identity and the Heroic

THE FILIPINO RINGSIDE COMMUNITY : NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE HEROIC MYTH OF MANNY PACQUIAO A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Margaret Louise Costello, B.A. Washington, DC April 30, 2009 THE FILIPINO RINGSIDE COMMUNITY : NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE HEROIC MYTH OF MANNY PACQUIAO Margaret Louise Costello, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Mirjana Dedaic, PhD ABSTRACT One of the main parallels between sport and national identity is that they are both maintained by ritual and symbolism. In the Philippine context, the spectator sport of boxing has grown to be a phenomenon in recent years, perhaps owing to the successive triumphs of contemporary Filipino pugilists in the international boxing scene. This thesis focuses on the case of Filipino boxer Manny Pacquiao whose matches bring together contemporary Philippine society into a “ringside community”, a collective united by its support of a single fighter bearing the brunt for the nation. I assert that Pacquiao’s stature has transcended that of the sports realm, as he is constructed as a national (i.e., not just sport) hero. As such, I study this phenomenon in two ways. The first part of my analysis focuses on how a narrative of heroism has been instilled in Philippine society through the active promotion of its past heroes. Inherent to this study’s discussion of the Filipino ringside community and heroism is the notion of the habitus. Defined by Pierre Bourdieu as a set of inculcated dispositions which generate practices and perceptions, “a present past that tends to perpetuate itself into the future by reactivation in similarly structured practices” (Bourdieu, 6), the concept of habitus can be directly applied to how the need for a heroic narrative has been inculcated within Philippine contemporary society. -

Community Driven City-Wide Process in Mongolia

SELAVIP MONGOLIA April 2010 E.J. Anzorea, SJ Community Driven City-Wide Process in Mongolia Housing Project in Tunkhel Village Project Scope Central part of the Tunkhel Village was built in • 1st kheseg of Tunkhel village, 55 residents of 1957. Maintenance period of the clay walls which are 16 households. 30 to 35 years old was ended. However, 55 persons from 16 households still live in very bad environment. Lesson Learned People who live here need to work together to We learned that in order to make city-wide improve living and housing conditions using all their change, it is more effective to start in small tasks. combined resources and capability. In order to become a city-wide process, we should have paid more attention to activities directed Project goal to benefit more communities. In Erdenet, Valentine • To support community-driven saving group SG implemented a project only within their fences, activities which did not affect other people. • To improve housing conditions of several Building bio latrines and waste classification households activities affected only people living near their • To have working asset for housing loan in fences. local level To provide sustainable operation of the SGs and 59 SELAVIP also, to build capacity, there is an essential need to develop short, medium, and long term plans. SGs also have to broaden their strategy for further development. • To find a solution to document the activities To improve cooperation between the local local area’s special characters and to create administration and SGs, there is a need to coordinate transparent reporting mechanism. -

Ready, but There Are Different Fonts Duterte Contra Deus

Ready, but there are different fonts Duterte Contra Deus Catholicism arrived in the Philippines in 1520 with Fernáo de Magãlhaes/Magellan. Almost 500 years later, the Church that helped to overthrow Ferdinand Marcos now faces two major challenges: how to fight another dictator and maintain the glory of the past in a society that is “more evangelized than catechized”? Patricia Fox, Regional Superior of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Sião Congregation, dedicated twenty- seven of her 72 years to the defense of the poor and oppressed in the Philippines. Accused of "involvement in illegal political activities", she was arrested on 16 April. On 3 November, she was expelled from the country, where she will not be able to return as a missionary. Upon arriving in Melbourne, after losing a tough legal battle, the Australian nun denounced President Rodrigo Duterte's “reign of tyranny”. “They have no right to criticize me”, said Duterte, who had ordered the deportation of Patricia Fox. He was indignant that she should have joined in a protest against the murder of farmers, but above all because she participated in an investigation of the extrajudicial executions he had ordered when he was Mayor of Davao, on the Island of Mindanao, in the south. Patricia Fox’s ordeal, and that of other members of the Catholic Church (three priests were shot in April and June of 2018, and in December 2017), shows the risk that one of the most influential institutions in the Philippines has had to face since Duterte won the elections in May 2016 to become Head of State, retaining a popularity of almost 80% despite the thousands of deaths. -

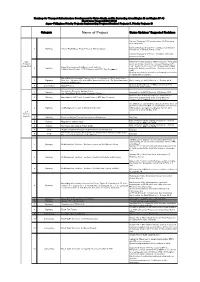

Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions

Roadmap for Transport Infrustructure Development for Metro Manila and Its Surrunding Areas(Region III and Region IV-A) Short-term Program(2014-2016) Japan-Philippines Priority Projects: Implementing Progress(Comitted Projects 5, Priority Projects 8) Category Name of Project Status Updates/ Suggested Revisions Contract Packages I & II covering about 14.65 km have been completed. Contract Package III (2.22 km + 2 bridges): Construction 1 Highways Arterial Road Bypass Project Phase II, Plaridel Bypass Progress as of 25 April 2015 is 13.02%. Contract Package IV (7.74 km + 2 bridges): Still under procurement stage. ODA Notice to Proceed Issued to CMX Consortium. The project Projects is not specifically cited in the Transport Roadmap. LRT (Committed) Line 1 South Ext and Line 2 East Ext were cited instead, Capacity Enhancement of Mass Transit Systems 2 Railways separately. Updates on LRT Line 1 South Extension and in Metro Manila Project (LRT1 Extension and LRT 2 East Extentsion) O&M: Ongoing pre-operation activities; and ongoing procurement of independent consultant. Metro Manila Interchanges Construction VI - 2 packages d. EDSA/ North Ave. - 3 Highways West Ave.- Mindanao Ave. and EDSA/ Roosevelt Ave. and f. C5: Green Meadows/ Confirmed by the NEDA Board on 17 October 2014 Acropolis/CalleIndustria Ongoing. Detailed Design is 100% accomplished. Final 4 Expressways CLLEX Phase I design plans under review. North South Commuter Railway Project 1 Railways Approved by the NEDA Board on 16 February 2015 (ex- Mega Manila North-South Commuter Railway) New Item, Line 2 West Extension not included in the 2 Railways Metro Manila CBD Transit System Project (LRT2 West Extension) short-term program (until 2016).