Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prologue to a Biography

Notes Preface and Acknowledgements 1. R. Skidelsky, ‘Introduction’, John Maynard Keynes, Vol. 3: Fighting for Britain 1937–1946 (Macmillan Papermac, 2000), p. xxii. 1 The Caribbean in Turmoil: Prologue to a Biography 1. Lewis Archive, Princeton, Box 1/10; ‘Autobiographical Account’ by Sir Arthur Lewis, prepared for Nobel Prize Committee, December 1979, p. 4. 2. Lewis (1939), p. 5. In the 1920s, the white population in St Lucia and on average across the islands, was relatively low, at about 3 per cent of the population. The proportion was higher than this on islands completely dominated by sugar cultivation, such as Barbados. 3. Lewis (1939), p. 7. On the significance of colour gradations in the social and power structures of the West Indies, see ‘The Light and the Dark’, ch.4 in James (1963) and Tignor (2005) notes: ‘In place of the rigid two-tiered racial system, there had appeared a coloured middle class … usually light skinned, well educated, professional and urban … To this generation, Lewis … belonged’ (p.11). 4. Lewis (1939), p. 5. 5. Lewis (1939), p. 9. 6. The total value of exports from St Lucia fell from £421,000 (£8.10 per cap- ita) to £207,000 (£3.91) between 1920 and 1925, and to £143,000 (£2.65) by 1930 (Armitage-Smith, 1931, p. 62). 7. These data derive from Sir Sydney Armitage-Smith’s financial mission to the Leeward Islands and St Lucia in the depths of the depression in 1931 – undertaken while Lewis was serving time in the Agricultural Department office waiting to sit his scholarship exam. -

Gender and the Development Agenda: Female Agency and Overseas Development, 1964-2018

Gender and the Development Agenda: female agency and overseas development, 1964-2018. Helen Ette | [email protected] | 160212420 | BA History | Supervisor: Dr Martin Farr Introduction Development: a token department for token women? Mainstreaming Women’s Rights With 2018 marking the centenary of the Representation of Discussion of Gender and International Development Judith Hart: ‘When I first went to the House of Commons, 100 the People Act 1918, the history of women in British politics 90 women were expected to concern themselves only with welfare 80 has been of particular public interest. Despite their 70 matters. The breakthrough into economics and foreign affairs 60 presence since its 1964 creation, the influence and 50 has only occurred during my time.’ 40 30 experience of women in the Department for International Press Releases on India visit July 1977, HART 07/02 Hart Papers, People’s History 20 10 Museum, Manchester. 0 Development (DFID) lacks scholarly attention. My project 1997 2000 2005 2010 2015 2018 provides a novel perspective to contemporary themes of Number of references to ‘women and girls’ and ‘international development’ in the House of Commons since the creation of DFID gender, diversity, and political agency. Valerie Amos: ‘I don’t consider development per se to be a • Millennium Development Goal Three, 2000-2015 feminine or feminist subject if you look at the elements of it …. • International Development (Gender Equality) Act, 2014 History of Female Cabinet Members since 1929 I know that there are notions around philanthropy … and that • Sustainable Development Goal Five, 2016-2030 women warped issues around concerns about family, women, Digital, Culture, Media, and Sport Changing language of women’s rights Leader of the House of Commons and girls, but I think it would be very simplistic to talk about Leader of the House of Lords development as a ‘female’ subject.’ ‘Family planning’ & ‘population control’ ‘poverty reduction’ Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs Interview by Helen Ette, 7 September 2018. -

Arthur Lewis at the London School of Economics 1933–1948

‘Marvellous intellectual feasts’: Arthur Lewis at the London School of Economics 1933–1948 1* Barbara Ingham 1 School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UK 2 * Corresponding author Paul Mosley [email protected] 2 University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK July 2010 [email protected] BWPI Working Paper 124 Brooks World Poverty Institute ISBN : 978-1-907247-23-1 Creating and sharing knowledge to help end poverty www.manchester.ac.uk/bwpi Abstract The paper is concerned with the decade and a half spent by the development economist, Arthur Lewis, at the London School of Economics between 1933 and 1948. It discusses the intellectual traditions of the institution that Lewis joined, and the various influences on the young economist. His research and teaching roles in London and Cambridge are covered, together with his work for the Fabian Society, and his links with the anti-imperialist movements centred in London in the 1930s and 1940s. The aim of the paper is to shed light on this highly significant but little known period in the career of the foremost development economist. Keywords: W.A. Lewis; LSE; colonial economics; development economics Barbara Ingham is Research Associate, Department of Economics, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UK. Paul Mosley is Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, University of Sheffield, UK. Acknowledgements: Research for the paper was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, with a grant awarded to Professor Paul Mosley of the University of Sheffield, UK, and Dr Barbara Ingham of the University of Salford, UK, in support of a project to produce an intellectual biography of Arthur Lewis. -

Labour Women in Power Paula Bartley Labour Women in Power

Labour Women in Power Paula Bartley Labour Women in Power Cabinet Ministers in the Twentieth Century Paula Bartley Stratford-upon-Avon, UK ISBN 978-3-030-14287-2 ISBN 978-3-030-14288-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14288-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932971 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG, part of Springer Nature 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affliations. -

The Lord Jay of Ewelme, Gcmg

BDOHP Biographical Details and Interview Index JAY, Michael Hastings GCMG (Baron Jay of Ewelme) (b. 16 June 1946) Career (with, on right, relevant pages in interview) Ministry of Overseas Development, 1969-73 p 4 UK Delegation, IMF-IBRD, Washington, 1973–75 pp 4-7 Ministry of Overseas Development, 1976–78 p 7 First Secretary (Aid), New Delhi, 1978–81 pp 7-13 Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 1981-85 pp 13-19 (Planning staff, 1981-82, pp 13-17; Private Secretary to Permanent Under-Secretary, 1982-85, pp 17-19) Counsellor: Cabinet Office, 1985–87 pp 19-25 Counsellor: (Financial and Commercial), Paris, 1987–90 pp 25-33 Assistant Under-Secretary of State for EC Affairs, FCO, 1990–93 pp 33-36 Deputy Under-Secretary of State (Director for EC and Economic pp 36-37 Affairs), FCO, 1994–96 Ambassador to France, 1996–2001 p 37 Permanent Under-Secretary of State, FCO and Head of the Diplomatic pp 37-49 Service, 2002–06 Prime Minister’s Personal Representative for G8 Summits, 2005–06 pp 50-51 1 THE LORD JAY OF EWELME GCMG (Sir Michael [Hastings] Jay) interviewed by Malcolm McBain at Ewelme, Oxon on 4 January 2007 Copyright: Lord Jay Education and family background MM: May I start by asking you a little about your family background and education, and how you came to come into the Government Service. MJ: My father spent his entire career – indeed most of his life – in the Navy. He went to Osborne in, I think, 1914 and then onto Dartmouth; he then joined the Navy where he stayed until he retired as a Captain in 1956 at the age of 52. -

A History of Force Feeding

A History of Force Feeding Ian Miller A History of Force Feeding Hunger Strikes, Prisons and Medical Ethics, 1909–1974 This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material. Ian Miller Ulster University Coleraine , United Kingdom ISBN 978-3-319-31112-8 ISBN 978-3-319-31113-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-31113-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016941754 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Reinventing Britain: British National Identity and the European Economic Community, 1967-1975

Reinventing Britain: British National Identity and the European Economic Community, 1967-1975 J. Meade Klingensmith Candidate for Senior Honors in History Leonard V. Smith, Thesis Advisor Submitted Spring 2012 Contents Preface/Acknowledgments 3 Introduction: “One Tiny, Damp Little Island” 7 Chapter One: The Two Wilsons: Harold Wilson and the 1967 EEC Application 23 Chapter Two: Keep Calm and Carry On: The 1967 EEC Debate in Public Discourse 37 Chapter Three: The Choice is Yours: The 1975 UK National Referendum 55 Chapter Four: England’s Dreaming: The 1975 Referendum in Public Discourse 69 Conclusion: The Song Remains the Same 83 Bibliography 87 2 Preface/Acknowledgments The thesis that you are now reading is substantially different from the one that I set out to write a year ago. I originally wanted to write about European integration. I, like many idealists before me, thought of regional political integration as the next step in the progression of civilization. I viewed the European Union as the first (relatively) successful experiment toward that end and wanted to conduct a study that would explore the problems associated with nations sacrificing their sovereignty and national identities in the name of integration, with the hope of exploring how those problems have been overcome in the past. Great Britain, as one of the European Union’s most prominent-yet-ambivalent members, jumped out to me as the perfect potential case study. I was fascinated by Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s attempt to convince Britons that joining with Europe was the right decision, by his potential kamikaze tactic of letting Britons decide for themselves in the country’s first-ever national referendum in 1975, and by their ultimate decision to stay in Europe despite decades of widespread resistance. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Beli & Howell Information Com pany 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 300/521-0600 Order Number 9307729 National role conceptions and foreign assistance policy behavior toward a cognitive model Breuning, Marijke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 Copyright ©1992 by Breurdng, Marÿke. -

Women and Parliaments in the UK

Women and Parliaments in the UK Revised July 2011 by Catriona Burness © The support of the JRSST Charitable Trust in producing this Handbook is gratefully acknowledged. The JRSST Charitable Trust is endowed by The Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. Front cover illustration Scottish Parliament Chamber Image © Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body – 2010 Sincere thanks to Brenda Graham for her help with proofreading and to Dr Françoise Barlet and to Kate Phillips for their comments on handbook drafts. Notes on the Author Dr Catriona Burness is an independent writer and consultant on politics. She has published many articles on the subject of women and politics and has worked at the universities of Dundee, Durham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and St Andrews. She has held study fellowships in Finland, New Zealand and Sweden and worked at the European Parliament in Brussels for ten years. Catriona Burness asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this book. The work is available on the basis that it may be used and circulated for non-commercial purposes and may not be adapted. ISBN: 978-0-9565140-3-5 Contents 4. Foreword 5. Introduction 6. House of Commons 9. Female Candidates and Elected MPs, October 1974-2010 10. Summary of Female MPs Elected 2010 11. Former Female Members of Parliament (MPs) 1918-2011 17. Current Female MPs, England 2011 21. Current Female MPs, Northern Ireland 2011 22. Current Female MPs, Scotland 2011 23. Current Female MPs, Wales 2011 24. National Assembly for Wales 27. Summary of Female Assembly Members (AMs) 1999-2011 28. Current Female Assembly Members (AMs) 2011 29. -

At Sharm El Sheikh on April 10

ANTI APARTHEID NEWS ANTI APARTHEID NEWS The hewspaper of the Anti-Apartheid Movement Vorster shops for arms in Israel 5 - at Sharm El Sheikh on April 10. In spite of official denials that war-plane plant and inspected its electronic security fence. -p1 n irua an israei are to esiaOisn a Joint milsterial committee to improve their economic relations, following Prime Minister Vorster's visit to Israel, April 9-12. The committee was set up in a ration - are covered by the formal pact s ied byVorster and Israeli pact. PnMinlstr Rabiawhich deals Israeli nuclear scientists wiU be with economcmi scientific and indus- includedinthefirstscientifictrialm ' missionwhich Israel will send to Details of Cooperation have South Africa asa result of the pact still to be worked out - but reports Other signs suggest that the suggest that South Africa could South African visit was a shopping export uranium to Israel, as well as trip for Israeli weapons. coal, iron ore; cement and semi- Vorater made a 'private visit' processedteel. fromwhichjournalistswere The trip was only the third time excluded - to the aircraft plant at that Vorster has travelied outside Lydda where Israei's Kfir (lion cub) Africa since he became Prime delta-wing warplane is manufactured. Minister - his other visits were to He visited the Golan Heights and Portugal and Spain in 1970 and to israel'stborder with Lebanot , Where Paraguay itn 195. hesawthecountry'selectronicAlthough officialson both sides security fence and defence network denied that defence issues were dis- in action. Used -

From Common Market to European Union: Creating a New Model State?

From Common Market to European Union: Creating a New Model State? Author: Peter Moloney Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/3797 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History FROM COMMON MARKET TO EUROPEAN UNION: CREATING A NEW MODEL STATE? A dissertation by PETER MOLONEY submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2014 © Copyright by PETER MOLONEY 2013 Dissertation Abstract From Common Market to European Union: Creating a New Model State? Peter Moloney Advisor: James Cronin In 1957, the Treaty of Rome was signed by six West European states to create the European Economic Community1 (EEC). Designed to foster a common internal market for a limited amount of industrial goods and to define a customs union within the Six, it did not at the time particularly stand out among contemporary international organizations.2 However, by 1992, within the space of a single generation, this initially limited trade zone had been dramatically expanded into the world’s largest trade bloc and had pooled substantial sovereignty among its member states on a range of core state responsibilities.3 Most remarkably, this transformation resulted from a thoroughly novel political experiment that combined traditional interstate cooperation among its growing membership with an unprecedented transfer of sovereignty to centralized institutions.4 Though still lacking the traditional institutions and legitimacy of a fully-fledged state, in many policy areas, the European Union (EU) that emerged in 1992 was nonetheless collectively a global force. -

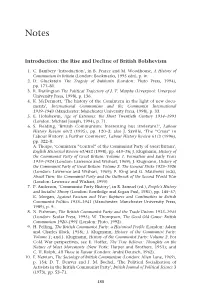

Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism

Notes Introduction: the Rise and Decline of British Bolshevism 1. C. Bambery ‘Introduction’, in B. Pearce and M. Woodhouse, A History of Communism In Britain (London: Bookmarks, 1995 edn), p. iv. 2. D. Gluckstein The Tragedy of Bukharin (London: Pluto Press, 1994), pp. 171–81. 3. R. Darlington The Political Trajectory of J. T. Murphy (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1998), p. 136. 4. K. McDermott, ‘The history of the Comintern in the light of new docu- ments’, International Communism and the Communist International 1919–1943 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 33. 5. E. Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: the Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991 (London: Michael Joseph, 1994), p. 71. 6. S. Fielding, ‘British Communism: Interesting but irrelevant?’, Labour History Review 60/2 (1995), pp. 120–3; also J. Saville, ‘The “Crisis” in Labour History: a Further Comment’, Labour History Review 61/3 (1996), pp. 322–8. A. Thorpe, ‘Comintern “Control” of the Communist Party of Great Britain’, English Historical Review 63/452 (1998), pp. 610–36; J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 1. Formation and Early Years 1919–1924 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); J. Klugmann, History of the Communist Party of Great Britain: Volume 2. The General Strike 1925–1926 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1969); F. King and G. Matthews (eds), About Turn: the Communist Party and the Outbreak of the Second World War (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1990). 7. P. Anderson, ‘Communist Party History’, in R. Samuel (ed.), People’s History and Socialist Theory (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981), pp. 145–57; K.