111 Historical Notes on Whooping Cranes at White

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masked Bobwhite (Colinus Virginianus Ridgwayi) 5-Year Review

Masked Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus ridgwayi) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photograph by Paul Zimmerman U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge Sasabe, AZ March 2014 5-YEAR REVIEW Masked Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus ridgwayi) 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Reviewers Lead Regional Office Southwest Region, Region 2, Albuquerque, NM Susan Jacobsen, Chief, Division of Classification and Restoration, 505-248-6641 Wendy Brown, Chief, Branch of Recovery and Restoration, 505-248-6664 Jennifer Smith-Castro, Recovery Biologist, 505-248-6663 Lead Field Office: Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge (BANWR) Sally Gall, Refuge Manager, 520-823-4251 x 102 Juliette Fernandez, Assistant Refuge Manager, 520-823-4251 x 103 Dan Cohan, Wildlife Biologist, 520-823-4351 x 105 Mary Hunnicutt, Wildlife Biologist, 520-823-4251 Cooperating Field Office(s): Arizona Ecological Services Tucson Field Office Jean Calhoun, Assistant Field Supervisor, 520-670-6150 x 223 Mima Falk, Senior Listing Biologist, 520-670-6150 x 225 Scott Richardson, Supervisory Fish and Wildlife Biologist, 520-670-6150 x 242 Mark Crites, Fish and Wildlife Biologist, 520-670-6150 x 229 Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Steve Spangle, Field Supervisor, 602-242-0210 x 244 1.2 Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service or USFWS) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). -

Wisconsin Bird Nesting Dates for Species Tracked by the Natural

Introduction to the “Wisconsin Bird Nesting Dates (Avoidance Period) for Species Tracked by the Natural Heritage Inventory” The table “Wisconsin Bird Nesting Dates (Avoidance Period) for Species Tracked by the Natural Heritage Inventory” below, provides guidance to DNR staff and external certified reviewers who use the NHI Portal for Endangered Resources reviews. This guidance was developed by a team of Natural Heritage Conservation program staff from DNR using the best available information for species on the Natural Heritage Working List. The Nesting Dates (Avoidance Period) table was developed to help customers comply with State and Federal laws and thus avoid “intentional taking, killing, or possession” of bird nests, eggs, and body parts. For each species, the avoidance dates are the period each year when birds are most vulnerable because there are eggs or flightless chicks in nests. Species tracked by the Natural Heritage Inventory include endangered, threatened and special concern species. Avoidance of these nesting dates is required for endangered and threatened species and recommended (voluntary) for special concern species. For more information on rare bird species, see the Rare Bird webpage. Revised 10/18/2019 https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/endangeredresources/documents/wisbirdnestingcalendar.pdf Wisconsin Bird Avoidance Dates for Species Tracked by the Natural Heritage Inventory Common Name Scientific Name Status Avoidance Dates Acadian Flycatcher Empidonax virescens THR 25 May - 20 Aug American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus SC/M -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Recovery Strategy for the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus Virginianus) in Canada

PROPOSED Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) in Canada Northern Bobwhite 2017 Recommended citation: Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2017. Recovery Strategy for the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. ix + 37 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry1. Cover illustration: © Dr. George K. Peck Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du Colin de Virginie (Colinus virginianus) au Canada [Proposition] » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2017. All rights reserved. ISBN Catalogue no. Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. 1 http://sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=24F7211B-1 Recovery Strategy for the Northern Bobwhite 2017 Preface The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry. -

252 Bird Species

Appendix 5: Fauna Known to Occur on Fort Drum LIST OF FAUNA KNOWN TO OCCUR ON FORT DRUM as of January 2017. Federally listed species are noted with FT (Federal Threatened) and FE (Federal Endangered); state listed species are noted with SSC (Species of Special Concern), ST (State Threatened, and SE (State Endangered); introduced species are noted with I (Introduced). BIRD SPECIES (Taxonomy based on The American Ornithologists’ Union’s 7th Edition Checklist of North American birds.) ORDER ANSERIFORMES ORDER CUCULIFORMES FAMILY ANATIDAE - Ducks & Geese FAMILY CUCULIDAE - Cuckoos Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Coccyzus americanus Yellow-billed Cuckoo Chen caerulescens Snow Goose Coccyzus erthropthalmusBlack-billed Cuckoo Chen rossii Ross’s Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose ORDER CAPRIMULGIFORMES Branta canadensis Canada Goose FAMILY CARPIMULGIDAE - Nightjars Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Chordeiles minor Common Nighthawk (SSC) Aix sponsa Wood Duck Antrostomus carolinensis Eastern Whip-poor-will Anas strepera Gadwall (SSC) Anas americana American Wigeon Anas rubripes American Black Duck ORDER APODIFORMES Anas platyrhynchos Mallard FAMILY APODIDAE – Swifts Anas discors Blue-winged Teal Chaetura pelagica Chimney Swift Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Anas acuta Northern Pintail FAMILY TROCHILIDAE – Hummingbirds Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Archilochus colubris Ruby-throated Hummingbird Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead ORDER GRUIFORMES Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck FAMILY RALLIDAE -

<I>Colinus Virginianus</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Natural Resources Natural Resources, School of 2012 Patterns of Incubation Behavior in Northern Bobwhites (Colinus virginianus) Jonathan S. Burnam University of Georgia, [email protected] Gretchen Turner University of Georgia, [email protected] Susan Ellis-Felege University of North Dakota, [email protected] William E. Palmer Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida, [email protected] D. Clay Sisson Albany Quail Project & Dixie Plantation Research, Albany, GA, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Ornithology Commons Burnam, Jonathan S.; Turner, Gretchen; Ellis-Felege, Susan; Palmer, William E.; Sisson, D. Clay; and Carroll, John P., "Patterns of Incubation Behavior in Northern Bobwhites (Colinus virginianus)" (2012). Papers in Natural Resources. 487. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/487 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Jonathan S. Burnam, Gretchen Turner, Susan Ellis-Felege, William E. Palmer, D. Clay Sisson, and John P. Carroll This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/487 CHAPTER SEVEN Patterns of Incubation Behavior in Northern Bobwhites Jonathan S. Burnam, Gretchen Turner, Susan N. Ellis-Felege, William E. Palmer, D. Clay Sisson, and John P. Carroll Abstract. Patterns of incubation and nesting parents took 0 – 3 recesses per day. -

Northern Bobwhite Colinus Virginianus Photo by SC DNR

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus Photo by SC DNR Contributor (2005): Billy Dukes (SCDNR) Reviewed and Edited (2012): Billy Dukes (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description In 1748, Catesby gave the Bobwhite quail the name Perdix sylvestris virginiana. In 1758, Linnaeus dropped the generic name Perdix and substituted Tetrao. The generic name Colinus was first used by Goldfuss in 1820 and, despite several ensuing name changes, became the accepted nomenclature (Rosene 1984). Bobwhite quail are members of the family Odontophoridae, the New World quail. Bobwhite quail are predominantly reddish-brown, with lesser amounts of white, brown, gray and black throughout. Both sexes have a dark stripe that originates at the beak and runs through the eye to the base of the skull. In males, the stripe above and below the eye is white, as is the throat patch. In females, this stripe and throat patch are light brown or tan. Typical weights for Bobwhites in South Carolina range from 160 to 180 g (5.6 to 6.3 oz.). Overall length throughout the range of the species is between 240 and 275 mm (9.5 and 10.8 in.) (Rosene 1984). Status Bobwhite quail are still widely distributed throughout their historic range. However, North American Breeding Bird Survey data indicate a significant range-wide decline of 3.8% annually between the years 1966 and 2009 (Sauer et al. 2004). In South Carolina, quail populations have declined at a rate of 6.1% annually since 1966 (Sauer et al. 2011). While not on the Partners in Flight Watch List, the concern for Northern Bobwhite is specifically mentioned Figure 1: Average summer distribution of northern bobwhite quail due to significant population declines 1994-2003. -

Bird Species

BIRD SPECIES Order: Podicipediformes Family: Podicipedidae Podilymbus podiceps pied-billed grebe Order: Ciconiiformes Family: Ardeidae Ardea herodias great blue heron Casmerodius albus great egret Egretta thula snowy egret Egretta caerulea little blue egret Bubulcus ibis cattle egret Butorides virescens green-backed heron Nycticorax nycticorax black-crowned night-heron Nyctanassa violacea yellow-crowned night-heron Order: Anseriformes Family: Anatidae Aix sponsa wood duck Anas crecca green-winged teal Anas rubripes American black duck Anas platyrhynchos mallard Anas acuta northern pintail Anas discors blue-winged teal Anas clypeata northern shoveler Anas strepera gadwall Anas americana American wigeon Aythya valisineria canvasback Aythya americana redhead Aythya collaris ring-necked duck Aythya marila greater scaup Aythya affinis lesser scaup Branta canadensis Canada goose Bucephla clangula common goldeneye Bucephala albeola bufflehead Lophodytes cucullatus hooded merganser Mergus merganser common merganser Mergus serrator red-breasted merganser Oxyura jamaicensis ruddy duck Chen caerulescens snow goose Order: Falconiformes Family: Cathartidae Coragyps atratus black vulture Cathartes aura turkey vulture Order: Falconiformes Family: Accipitridae Elanoides forficatus American swallow-tailed kite Haliaeetus leucocephalus bald eagle Circus cyaneus northern harrier Accipiter striatus sharp-shinned hawk Accipiter cooperii Cooper's hawk Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk Buteo platypterus broad-winged hawk Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk Aquila -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Birds Accipitridae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Osprey Pandion

Birds Accipitridae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Osprey Pandion haliaetus Northern Harrier Hawk Circus cyaneus Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus Sharp-shinned Hawk Accipiter striatus Cooper’s Hawk Accipiter cooperii Red-shoulder Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Red-tailed Hawk Buteo jamaicensis Alcedinidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon Anatidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus Snow Goose Chen caerulescens Canada Goose Branta canadensis Wood Duck Aix sponsa Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata Mallard Anas platyrhynchos American Black Duck Anas rubripes Gadwall Anas strepera Green-winged Teal Anas crecca American Wigeon Anas americana Northern Pintail Anas acuta Northern Shoveler Anas clypeata Blue-winged Teal Anas discors Canvasback Aythya valisineria Redhead Aythya americana Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Greater Scaup Aythya marila Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator Hooded Merganser Lophodytes cucullatus Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Anhingidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Apodidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Chimney Swift Chaetura pelagica Ardeidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Black-crowned Night-Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Green Heron Butorides virescens Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis Snowy Egret Egretta thula Great Egret Ardea alba Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Bombycillidae COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME Cedar Waxwing Bombycilla cedrorum Caprimulgidae -

Bird Checklist

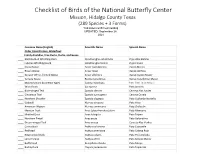

Checklist of Birds of the National Butterfly Center Mission, Hidalgo County Texas (289 Species + 3 Forms) *indicates confirmed nesting UPDATED: September 28, 2021 Common Name (English) Scientific Name Spanish Name Order Anseriformes, Waterfowl Family Anatidae, Tree Ducks, Ducks, and Geese Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis Pijije Alas Blancas Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Pijije Canelo Snow Goose Anser caerulescens Ganso Blanco Ross's Goose Anser rossii Ganso de Ross Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons Ganso Careto Mayor Canada Goose Branta canadensis Ganso Canadiense Mayor Muscovy Duck (Domestic type) Cairina moschata Pato Real (doméstico) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Pato Arcoíris Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors Cerceta Alas Azules Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cerceta Canela Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata Pato Cucharón Norteño Gadwall Mareca strepera Pato Friso American Wigeon Mareca americana Pato Chalcuán Mexican Duck Anas (platyrhynchos) diazi Pato Mexicano Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula Pato Tejano Northern Pintail Anas acuta Pato Golondrino Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Cerceta Alas Verdes Canvasback Aythya valisineria Pato Coacoxtle Redhead Aythya americana Pato Cabeza Roja Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris Pato Pico Anillado Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis Pato Boludo Menor Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Pato Monja Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis Pato Tepalcate Order Galliformes, Upland Game Birds Family Cracidae, Guans and Chachalacas Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula Chachalaca Norteña Family Odontophoridae, -

Version 8.0.5 - 12/19/2018 • 1112 Species • the ABA Checklist Is a Copyrighted Work Owned by American Birding Association, Inc

Version 8.0.5 - 12/19/2018 • 1112 species • The ABA Checklist is a copyrighted work owned by American Birding Association, Inc. and cannot be reproduced without the express written permission of American Birding Association, Inc. • 93 Clinton St. Ste. ABA, PO BOX 744 Delaware City, DE 19706, USA • (800) 850-2473 / (719) 578-9703 • www.aba.org The comprehensive ABA Checklist, including detailed species accounts, and the pocket-sized ABA Trip List can be purchased from ABA Sales at http:// www.buteobooks.