Universitat Autònoma De Barcelona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Deal – the Coordinators

Green Deal – The Coordinators David Sassoli S&D ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first European Parliament and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be 1 February 2020 – H1 2024 the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle President of the European Commission Head of Cabinet Secretary General Chairs and Vice-Chairs Political Group Coordinators EPP S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe ENVI Renew Committee on Europe Dan-Ştefan Motreanu César Luena Peter Liese Jytte Guteland Nils Torvalds Silvia Sardone Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator the Environment, Public Health Greens/EFA GUE/NGL Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Food Safety Pacal Canfin Chair Bas Eickhout Anja Hazekamp Bas Eickhout Alexandr Vondra Silvia Modig Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator S&D S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe EPP ITRE Patrizia Toia Lina Gálvez Muñoz Christian Ehler Dan Nica Martina Dlabajová Paolo Borchia Committee on Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Industry, Research Renew ECR Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Energy Cristian Bușoi Europe Chair Morten Petersen Zdzisław Krasnodębski Ville Niinistö Zdzisław Krasnodębski Marisa Matias Vice-Chair Vice-Chair -

Northeast Asia: Obstacles to Regional Integration the Interests of the European Union

Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Discussion Paper Ludger Kühnhardt Northeast Asia: Obstacles to Regional Integration The Interests of the European Union ISSN 1435-3288 ISBN 3-936183-52-X Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Walter-Flex-Straße 3 Tel.: +49-228-73-4952 D-53113 Bonn Fax: +49-228-73-1788 C152 Germany http: //www.zei.de 2005 Prof. Dr. Ludger Kühnhardt, born 1958, is Director at the Center for European Integration Studies (ZEI). Between 1991 and 1997 he was Professor of Political Science at Freiburg University, where he also served as Dean of his Faculty. After studies of history, philosophy and political science at Bonn, Geneva, Tokyo and Harvard, Kühnhardt wrote a dissertation on the world refugee problem and a second thesis (Habilitation) on the universality of human rights. He was speechwriter for Germany’s Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker and visiting professor at various universities all over the world. His recent publications include: Europäische Union und föderale Idee, Munich 1993; Revolutionszeiten. Das Umbruchjahr 1989 im geschichtlichen Zusammenhang, Munich 1994 (Turkish edition 2003); Von der ewigen Suche nach Frieden. Immanuel Kants Vision und Europas Wirklichkeit, Bonn 1996; Beyond divisions and after. Essays on democracy, the Germans and Europe, New York/Frankfurt a.M. 1996; (with Hans-Gert Pöttering) Kontinent Europa, Zurich 1998 (Czech edition 2000); Zukunftsdenker. Bewährte Ideen politischer Ordnung für das dritte Jahrtausend, Baden-Baden 1999; Von Deutschland nach Europa. Geistiger Zusammenhalt und außenpoliti- scher Kontext, Baden-Baden 2000; Constituting Europe, Baden- Baden 2003. -

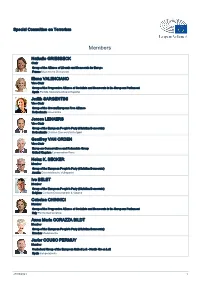

List of Members

Special Committee on Terrorism Members Nathalie GRIESBECK Chair Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe France Mouvement Démocrate Elena VALENCIANO Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Spain Partido Socialista Obrero Español Judith SARGENTINI Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Netherlands GroenLinks Jeroen LENAERS Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Netherlands Christen Democratisch Appèl Geoffrey VAN ORDEN Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group United Kingdom Conservative Party Heinz K. BECKER Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Austria Österreichische Volkspartei Ivo BELET Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Belgium Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams Caterina CHINNICI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Anna Maria CORAZZA BILDT Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Sweden Moderaterna Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente 27/09/2021 1 Edward CZESAK Member European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) France Les Républicains Gérard DEPREZ Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Belgium Mouvement Réformateur Agustín -

EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'esquerra INDEPENDENTISTA Publicació D’EndavantOSAN: La Barraqueta C

ENDAVANT OSAN endavant.org EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'ESQUERRA INDEPENDENTISTA PublicaciÓ d’EndavantOSAN: La Barraqueta C. Tordera, 30 (08012 Barcelona) RacÓ de la Corbella C. Maldonado, 46 (46001 ValÈncia) Ateneu Popular de Palma C. MissiÓ, 19 (07011 Palma) Contacte: [email protected] 1 EL PROCÉS SOBIRANISTA I L'ESQUERRA INDEPENDENTISTA El procÉs sobiranista i l'esquerra independentista Els objectius fonamentals de l'esquerra independentista 3 D'on ve l'actual procÉs sobiranista? 4 Quines sÓn les caracterÍstiques de l'independentisme majoritari avui en dia? 7 El paper de les elits econÒmiques 9 Perspectives de canvi social 12 El procÉs sobiranista i els PaÏsos Catalans 14 Objectius, etapes i lÍnies d'actuaciÓ en els propers mesos 17 endavant.org 2 Els objectius fonamentals de l'esquerra independentista L'objectiu final de l'esquerra independentista És la independÈncia, el socialisme i el feminisme als PaÏsos Catalans. És a dir, la constituciÓ d'un estat independent que englobi el conjunt de la naciÓ catalana i la construcciÓ d'una societat socialista i fe minista. Qualsevol actuaciÓ polÍtica, des de la intervenciÓ en una lluita conjuntural fins a les estratÈgies polÍtiques nacionals o territorials, ha d'anar encaminada a l'acumulaciÓ de forces per a poder assolir aquest objectiu final que És la raÓ de ser del nostre moviment. Per tant, la mobilitzaciÓ independentista que actualment viu el Principat de Catalu nya, tambÉ cal que la inserim en aquesta mateixa lÒgica d'analitzarla i intervenirhi polÍticament amb l'objectiu d'acumular forces i avanÇar cap a la consecuciÓ del nos tre projecte polÍtic. -

EU-Parlament: Ausschussvorsitzende Und Deren Stellvertreter*Innen Auf Den Konstituierenden Sitzungen Am Mittwoch, 10

EU-Parlament: Ausschussvorsitzende und deren Stellvertreter*innen Auf den konstituierenden Sitzungen am Mittwoch, 10. Juli 2019, haben die siebenundzwanzig permanenten Ausschüsse des EU-Parlaments ihre Vorsitzenden und Stellvertreter*innen gewählt. Nachfolgend die Ergebnisse (Reihenfolge analog zur Auflistung auf den Seiten des Europäischen Parlaments): Ausschuss Vorsitzender Stellvertreter Witold Jan WASZCZYKOEDKI (ECR, PL) AFET Urmas PAET (Renew, EE) David McALLISTER (EPP, DE) Auswärtige Angelegenheiten Sergei STANISHEV (S&D, BG) Željana ZOVKO (EPP, HR) Bernard GUETTA (Renew, FR) DROI Hannah NEUMANN (Greens/EFA, DE) Marie ARENA (S&D, BE) Menschenrechte Christian SAGARTZ (EPP, AT) Raphael GLUCKSMANN (S&D, FR) Nikos ANDROULAKIS (S&D, EL) SEDE Kinga GÁL (EPP, HU) Nathalie LOISEAU (RE, FR) Sicherheit und Verteidigung Özlem DEMIREL (GUE/NGL, DE) Lukas MANDL (EPP, AT) Pierrette HERZBERGER-FOFANA (Greens/EFA, DE) DEVE Norbert NEUSER (S&D, DE) Tomas TOBÉ (EPP, SE) Entwicklung Chrysoula ZACHAROPOULOU (RE, FR) Erik MARQUARDT (Greens/EFA, DE) Seite 1 14.01.2021 Jan ZAHRADIL (ECR, CZ) INTA Iuliu WINKLER (EPP, RO) Bernd LANGE (S&D, DE) Internationaler Handel Anna-Michelle ASIMAKOPOULOU (EPP, EL) Marie-Pierre VEDRENNE (RE, FR) Janusz LEWANDOWSKI (EPP, PL) BUDG Oliver CHASTEL (RE, BE) Johan VAN OVERTVELDT (ECR, BE) Haushalt Margarida MARQUES (S&D, PT) Niclas HERBST (EPP, DE) Isabel GARCÍA MUÑOZ (S&D, ES) CONT Caterina CHINNICI (S&D, IT) Monika HOHLMEIER (EPP, DE) Haushaltskontrolle Martina DLABAJOVÁ (RE, CZ) Tamás DEUTSCH (EPP, HU) Luděk NIEDERMAYER -

The European Campaign to End the Siege on Gaza (ECESG) Is an Anti-Israel, Pro-Hamas Umbrella Organization Which Participated in the Mavi Marmara Flotilla

The Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center October 5, 2010 The European Campaign to End the Siege on Gaza (ECESG) is an anti-Israel, pro-Hamas umbrella organization which participated in the Mavi Marmara flotilla. The ECESG is currently involved in organizing an upgraded flotilla, and in other projects to further isolate Israel, part of the campaign to delegitimize it. The Sfendoni 8000, the ECESG's vessel in the Mavi Marmara flotilla. The number refers to the 8000 Palestinian terrorists detained by Israel. 253-10 2 Overview 1. The European Campaign to End the Siege on Gaza (ECESG) is an anti-Israel, pro Hamas umbrella organization operating in Europe. It participated in the last flotilla (which ended with a violent confrontation aboard the Mavi Marmara) along with a coalition of four other anti-Israel organizations led by the Turkish IHH. Since then the ECESG and the other coalition members have been intensively promoting new programs with the objective of embarrassing Israel and deepening its isolation. The coalition projects include an upgraded flotilla which has been organizing for several months as Freedom Fleet 2 (its organizers hope to include more than 20 ships from various countries), and sending a plane to the Gaza Strip. 2. The ECESG was founded in 2007, the same year as Hamas' violent takeover of the Fatah and Palestinian Authority institutions in the Gaza Strip. Its declared objectives are "the complete lifting" of the so-called Israeli "siege" of the Gaza Strip and bringing humanitarian assistance to its residents. However, beyond that goal, which is supported by Western human rights organizations and activists, lie hidden its undeclared political objectives. -

Italie / Italy

ITALIE / ITALY LEGA (LIGUE – LEAGUE) Circonscription nord-ouest 1. Salvini Matteo 11. Molteni Laura 2. Andreina Heidi Monica 12. Panza Alessandro 3. Campomenosi Marco 13. Poggio Vittoria 4. Cappellari Alessandra 14. Porro Cristina 5. Casiraghi Marta 15. Racca Marco 6. Cattaneo Dante 16. Sammaritani Paolo 7. Ciocca Angelo 17. Sardone Silvia Serafina (eurodeputato uscente) 18. Tovaglieri Isabella 8. Gancia Gianna 19. Zambelli Stefania 9. Lancini Danilo Oscar 20. Zanni Marco (eurodeputato uscente) (eurodeputato uscente) 10. Marrapodi Pietro Antonio Circonscription nord-est 1. Salvini Matteo 8. Dreosto Marco 2. Basso Alessandra 9. Gazzini Matteo 3. Bizzotto Mara 10. Ghidoni Paola (eurodeputato uscente) 11. Ghilardelli Manuel 4. Borchia Paolo 12. Lizzi Elena 5. Cipriani Vallì 13. Occhi Emiliano 6. Conte Rosanna 14. Padovani Gabriele 7. Da Re Gianantonio detto Toni 15. Rento Ilenia Circonscription centre 1. Salvini Matteo 9. Pastorelli Stefano 2. Baldassarre Simona Renata 10. Pavoncello Angelo 3. Adinolfi Matteo 11. Peppucci Francesca 4. Alberti Jacopo 12. Regimenti Luisa 5. Bollettini Leo 13. Rinaldi Antonio Maria 6. Bonfrisco Anna detta Cinzia 14. Rossi Maria Veronica 7. Ceccardi Susanna 15. Vizzotto Elena 8. Lucentini Mauro Circonscription sud 1. Salvini Matteo 10. Lella Antonella 2. Antelmi Ilaria 11. Petroni Luigi Antonio 3. Calderano Daniela 12. Porpiglia Francesca Anastasia 4. Caroppo Andrea 13. Sapignoli Simona 5. Casanova Massimo 14. Sgro Nadia 6. Cerrelli Giancarlo 15. Sofo Vincenzo 7. D’Aloisio Antonello 16. Staine Emma 8. De Blasis Elisabetta 17. Tommasetti Aurelio 9. Grant Valentino 18. Vuolo Lucia Circonscription insulaire 1. Salvini Matteo 5. Hopps Maria Concetta detta Marico 2. Donato Francesca 6. Pilli Sonia 3. -

Spotlight Europe # 2009/08 – September 2009 Europe Begins at Home

spotlight europe # 2009/08 – September 2009 Europe begins at home Joachim Fritz-Vannahme Bertelsmann Stiftung, [email protected] The European policy of the forthcoming German government is bound to change, partly as a result of the new institutional framework. On the one hand there is the ruling of the German Constitutional Court. And on the other hand it will become necessary to play by the EU’s new rules of the game. Can Germany continue to support the trend to more European in- tegration and, more importantly, will it have a desire to do so? Whoever becomes the next Chancellor of I Germany will have to get used to new rules of the game in the area of European policy. They have been determined in two The Ruling in Karlsruhe – different ways. On the one hand the ruling Criticism and Praise of the German Constitutional Court on the Treaty of Lisbon redistributes the tasks The Karlsruhe ruling on 30 June 2009 led assigned to various German institutions. to fierce disputes in Germany and else- # 2009/08 And on the other hand the Treaty itself–if, where among those who sought to that is, the Irish give their assent to it on elucidate its meaning. Writing in the 02 October, for otherwise there will be a weekly newspaper “Die Zeit,” former need for crisis management for years to foreign minister Joschka Fischer criticized come–will change the distribution of the fact that it placed “national power in Brussels, partly on account of the constraints” on European integration. creation of new posts ranging from the “Karlsruhe simply does not like the EU’s permanent President of the European progress towards deeper integration,” Council to the EU foreign policy represen- writes Fischer. -

Manifesto 52 Former MEP Immunity of Carles

March 5, 2021 On February 23, the Committee on Legal Affairs of the European Parliament voted in favour (15 votes in favour including the votes of the Spanish parties PP, PSOE, Ciudadanos and the far- right VOX; 8 against and 2 abstentions), of a report that recommends to the Plenary to lift the immunity of our colleagues MEPs Carles Puigdemont, Toni Comín and Clara Ponsatí. The vote on this report will take place in the next plenary session, taking place next week.. The undersigned, former Members of the European Parliament, call on the Members of the European Parliament who are to take part in this vote, to vote against this proposal and therefore in favour of protecting the immunity of their colleagues Mr. Puigdemont, Mr. Comín and Ms. Ponsatí. First, because the court that requests the waiver of their immunity, the Spanish Supreme Court, is not the competent authority to make the request, as it was argued before the JURI Committee, and neither is it an impartial court, as recently established by the Belgian justice, since the Brussels Court of Appeals found that Lluís Puig, former Minister of the Catalan Government in exile, could not be impartially judged by this Spanish Court. Second, there is evidence that these three Members of the European Parliament are suffering political persecution. This political persecution is based on evidence, such as the judicial obstacles to prevent them from running in the European elections, the presence of up to five Spanish MEPs on the JURI Committee and their public statements on the report before, during, and after the vote; the inclusion of wrong charges in the report of Clara Ponsatí; or the leaking of the report before the vote to a far-right newspaper in Spain. -

Pierwsze Notowania Rządu Ewy Kopacz

Warszawa, październik 2014 ISSN 2353-5822 NR 145/2014 PIERWSZE NOTOWANIA RZĄDU EWY KOPACZ Znak jakości przyznany CBOS przez Organizację Firm Badania Opinii i Rynku 14 stycznia 2014 roku Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej ul. Świętojerska 5/7, 00-236 Warszawa e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] http://www.cbos.pl (48 22) 629 35 69 Okoliczności powołania rządu Ewy Kopacz są nietypowe. Dotychczas do zmiany premiera w trakcie kadencji Sejmu dochodziło zazwyczaj w efekcie negatywnych zjawisk i procesów na scenie politycznej, np. takich jak podważenie osobistej wiarygodności szefa rządu, brak stabilnej większości parlamentarnej czy wyczerpanie się społecznego poparcia dla ustępującego gabinetu. Tym razem powołanie nowego rządu nastąpiło w wyniku awansu premiera z polityki polskiej do europejskiej. Oprócz prezesa Rady Ministrów z rządu odeszła wicepremier Elżbieta Bieńkowska, która została unijnym komisarzem ds. rynku wewnętrznego i usług, przemysłu, przedsiębiorczości oraz małych i średnich przedsiębiorstw. Mimo tych zmian skład personalny nowego rządu jest zbliżony do składu poprzedniego gabinetu, większość ministrów bowiem zachowała swoje stanowiska. Wprawdzie odejście Donalda Tuska z krajowej polityki – w przekonaniu nie tylko wielu komentatorów politycznych, ale także znacznej części opinii publicznej w Polsce – osłabia Platformę Obywatelską i współtworzony przez nią rząd1, ale jednocześnie stwarza szansę na kolejne „nowe otwarcie” i odbudowanie nadwyrężonego wizerunku rządzącej partii. Rząd Ewy Kopacz budzi umiarkowanie pozytywne reakcje2. W to, że sytuacja w kraju się poprawi w wyniku działań nowego gabinetu, wierzy 36% badanych. Niepokój przed pogorszeniem wyraża 15% ankietowanych. Prawie jedna piąta (19%) uważa, że nic się nie zmieni. 1 Por. komunikat CBOS „Polska polityka po nominacji Donalda Tuska na szefa Rady Europejskiej”, wrzesień 2014 (oprac. -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

European Parliament Elections 2014

European Parliament Elections 2014 Updated 12 March 2014 Overview of Candidates in the United Kingdom Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 CANDIDATE SELECTION PROCESS ............................................................................................. 2 3.0 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS: VOTING METHOD IN THE UK ................................................................ 3 4.0 PRELIMINARY OVERVIEW OF CANDIDATES BY UK CONSTITUENCY ............................................ 3 5.0 ANNEX: LIST OF SITTING UK MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ................................ 16 6.0 ABOUT US ............................................................................................................................. 17 All images used in this briefing are © Barryob / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL © DeHavilland EU Ltd 2014. All rights reserved. 1 | 18 European Parliament Elections 2014 1.0 Introduction This briefing is part of DeHavilland EU’s Foresight Report series on the 2014 European elections and provides a preliminary overview of the candidates standing in the UK for election to the European Parliament in 2014. In the United Kingdom, the election for the country’s 73 Members of the European Parliament will be held on Thursday 22 May 2014. The elections come at a crucial junction for UK-EU relations, and are likely to have far-reaching consequences for the UK’s relationship with the rest of Europe: a surge in support for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) could lead to a Britain that is increasingly dis-engaged from the EU policy-making process. In parallel, the current UK Government is also conducting a review of the EU’s powers and Prime Minister David Cameron has repeatedly pushed for a ‘repatriation’ of powers from the European to the national level. These long-term political developments aside, the elections will also have more direct and tangible consequences.