The Abstract Edge Robert Davidson and Contemporary Aboriginal Arts Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Reid Gallery Re-Opens ANd Commemorates 100Th Anniversary of One of Canada's Most Renowned Indigenous Artists In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE June 9, 2020 Bill Reid Gallery Re-opens and Commemorates 100th Anniversary of One of Canada’s Most Renowned Indigenous Artists in – To Speak With a Golden Voice – Exhibition brings fresh perspective to Bill Reid’s legacy with rarely seen artworks and new commissions by Northwest Coast artists inspired by his life and practice VANCOUVER, BC — Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art re-opens the gallery and celebrates the milestone centennial birthday of Bill Reid (1920–1998) with an exhibition about his extraordinary life and legacy, To Speak With a Golden Voice, from July 16, 2020 to April 11, 2021. Guest curated by Gwaai Edenshaw — considered to be Reid’s last apprentice — the group exhibition includes rarely seen treasures by Reid and works from artists such as Robert Davidson and Beau Dick. Tracing the iconic Haida artist’s lasting influence, two new artworks by contemporary artist Cori Savard (Haida) and singer-songwriter Kinnie Starr (Mohawk/Dutch/German//Irish) will be created for this highly anticipated exhibition. “Bill Reid was a master goldsmith, sculptor, community activist, and mentor whose lasting legacy and influence has been cemented by his fusion of Haida traditions with his own modernist aesthetic,” says Edenshaw. “Just about every Northwest Coast artist working today has a connection or link to Reid. Before he became renowned for his artwork, he was a CBC radio announcer recognized for his memorable voice — in fact, one of Reid’s many Haida names was Kihlguulins, or ‘golden voice.’ His role as a public figure helped him become a pivotal force in the resurgence of Northwest Coast art, introducing the world to its importance and empowering generations of artists.” Reid was born in Victoria, BC, to a Haida mother and an American father with Scottish-German roots. -

Dick Polich in Art History

ww 12 DICK POLICH THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY BY DANIEL BELASCO > Louise Bourgeois’ 25 x 35 x 17 foot bronze Fountain at Polich Art Works, in collaboration with Bob Spring and Modern Art Foundry, 1999, Courtesy Dick Polich © Louise Bourgeois Estate / Licensed by VAGA, New York (cat. 40) ww TRANSFORMING METAL INTO ART 13 THE CONDUCTOR: DICK POLICH IN ART HISTORY 14 DICK POLICH Art foundry owner and metallurgist Dick Polich is one of those rare skeleton keys that unlocks the doors of modern and contemporary art. Since opening his first art foundry in the late 1960s, Polich has worked closely with the most significant artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. His foundries—Tallix (1970–2006), Polich of Polich’s energy and invention, Art Works (1995–2006), and Polich dedication to craft, and Tallix (2006–present)—have produced entrepreneurial acumen on the renowned artworks like Jeff Koons’ work of artists. As an art fabricator, gleaming stainless steel Rabbit (1986) and Polich remains behind the scenes, Louise Bourgeois’ imposing 30-foot tall his work subsumed into the careers spider Maman (2003), to name just two. of the artists. In recent years, They have also produced major public however, postmodernist artistic monuments, like the Korean War practices have discredited the myth Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC of the artist as solitary creator, and (1995), and the Leonardo da Vinci horse the public is increasingly curious in Milan (1999). His current business, to know how elaborately crafted Polich Tallix, is one of the largest and works of art are made.2 The best-regarded art foundries in the following essay, which corresponds world, a leader in the integration to the exhibition, interweaves a of technological and metallurgical history of Polich’s foundry know-how with the highest quality leadership with analysis of craftsmanship. -

Robert Davidson Portfolio

Robert Davidson (b.1946) ARTIST BIOGRAPHY Robert Davidson, of Haida and Tlingit descent, is one of Canada’s most respected contemporary artists and central to the renaissance of Northwest Pacific indigenous art. He has championed the rich art tradition of his native Haida Gwaii, consistently searching ‘for the “soul” he saw in the art of his Haida elders’. As he works in both classical form and contemporary minimalism, Davidson negotiates a delicate edge between the ancestral and the individual, infusing traditional forms with an evolutionary spirit. Awards include National Aboriginal Achievement Award for Art and Culture, Order of British Columbia, Order of Canada, Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal, British Columbia Aboriginal Art Lifetime Achievement Award, Governor General’s Award, and the commemorative medal marking the 60th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s accession to the throne as Queen of Canada and honouring significant achievements by Canadians. Robert Davidson CV EDUCATION: In 1966 Davidson became apprenticed to the master Haida carver Bill Reid and in 1967 he began studies at the Vancouver School of Art. EXHIBITIONS | SELECTED 2015 – Robert Davidson: Progression of Form,Gordon Smith Gallery, North Vancouver, BC 2014 – Abstract Impulse, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA Abstract Impulse, National Museum of the North American Indian, New York, NY 2011 – The Art of Robert Davidson, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA 2010 – Visions of British Columbia: A Landscape Manual, Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC Haida Art — Mapping -

Resource for English As a Second Language Teachers and Students

UBC Museum of Anthropology Resource for English Second Language Teachers & Students Credits: Cover Photos, Left to Right: The Raven and the First Men, Haida, by Bill Reid, 1980, Nb1.481; Haida Frontal Pole, Tanoo, A50000 a-d; Tsimalano House Board, Musqueam, A50004. All photographs UBC Museum of Anthropology. Produced by the Education and Public Programs offi ce of the UBC Museum of Anthropology under the direction of Jill Baird, Education Curator. Signifi cant contributions to this resource were made by: Copy editing: Jan Selman Graphic design: Joanne White Research and development: Jill Baird, Curator of Education and Public Programs Kay Grandage, MOA Volunteer Associate Christine Hoppenrath, ESL Instructor, Vancouver Community College Diane Fuladi, English Language Instructor © UBC Museum of Anthropology 6393 N.W. Marine Drive Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z2 Tel: 604-822-5087 www.moa.ubc.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS ESL RESOURCE TABLE OF CONTENTS ESL Resource Introduction ............................................................................ pg 4 ESL Resource Overview ................................................................................. pg 5 Teacher Background Information Contents ...................................................................................................pg 7 Introduction to First Nations of British Columbia ............................... pg 8-14 First Nations Vocabulary for Teachers ............................................. pg 15-19 Resources for Additional Research ................................................. -

Gareth Moore, James Hart: the Dance Screen and Emily Carr in Haida Gwaii

In Dialogue with Carr: Gareth Moore, James Hart: The Dance Screen and Emily Carr in Haida Gwaii Emily Carr Totem and Forest, 1931 oil on canvas Collection of Vancouver Art Gallery, Emily Carr Trust TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE Fall 2013 Contents Program Information and Goals ................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition In Dialogue with Carr: Gareth Moore ........................................................ 4 Background to the Exhibition James Hart: The Dance Screen................................................................. 5 Background to the Exhibition Emily Carr in Haida Gwaii .......................................................................... 6 Artists’ Background ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Northwest Coast Haida Art: A Brief Introduction ....................................................................................... 9 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. Connecting the Artists ........................................................................................................... 11 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 12 Student Worksheet................................................................................................................ 13 2. Sketch and Paint................................................................................................................... -

Grade 7-8: the Arts Haida Totem Poles

ELEMENTARY LESSON GRADE 7-8: THE ARTS HAIDA TOTEM POLES Purpose: Students will study the distinct style of Haida art various parts of the world.” Carr feared for the future of this aspect specifically focusing on the significance and purpose of totem of First Nations culture. Carr’s paintings are not photographic in poles. They will then apply their learnings by drawing their own their depiction because Carr believed it was more important totem pole. to capture the spirit of the communities she visited—both deserted and populated—in order to create an accurate historical memory. Estimated time: 90 minutes A few Canadian artists, including Bill Reid and Robert Davidson, Resources required: have revived the disappearing art style of the Haida. In 1969, o Large blank paper Robert Davidson carved and erected the first totem pole in his o Select art supplies (i.e. pencil crayons, charcoal, pastels, etc.) hometown of Masset, British Columbia—a remote fishing village on the north coast of Haida Gwaii—in nearly a century. Activity: 1. Begin the class by asking students to share what they know Once erected, totem poles are often not maintained, but are left to about totem poles (e.g., what they are, what they are made the elements to weather and age naturally. Therefore, the from, where they can be found, etc.). bright paint becomes faded and the sharp features soften as time passes. 2. Tell students that totem poles are believed to have originated with the Haida people of Haida Gwaii off the West Coast of 3. Show students some examples of Haida totem poles and Canada (also known as the Queen Charlotte Islands). -

The Black Canoe: Bill Reid and the Spirit of Haida Gawaii

Document généré le 27 sept. 2021 18:05 Espace Sculpture The Black Canoe Bill Reid and The Spirit of Haida Gawaii John K. Grande Sculpture et anthropologie Numéro 19, printemps 1992 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/10021ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Le Centre de diffusion 3D ISSN 0821-9222 (imprimé) 1923-2551 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Grande, J. K. (1992). The Black Canoe: Bill Reid and The Spirit of Haida Gawaii. Espace Sculpture, (19), 30–33. Tous droits réservés © Le Centre de diffusion 3D, 1992 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ^^ •Jjjuyjuu The Black Canoe BILL REID AND THE SPIRIT OF HAIDA GAWAII John K. Grande ooking for all the world like the last survivors from a Li grea t natural disaster, or a motley crew of mythical expatriates embarked on a journey to who knows where, the profusion of half-human, half-animal characters thatpopulate Bill Reid's The Black Canoe aren't the typical ones one would expect to meet up with in Washington D.C. -

Miniaturisation: a Study of a Material Culture Practice Among the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest

Miniaturisation: a study of a material culture practice among the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest John William Davy Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Department of Anthropology, University College London (UCL), through a Collaborative Doctoral Award partnership with The British Museum. Submitted December, 2016 Corrected May, 2017 94,297 words Declaration I, John William Davy, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where material has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. John William Davy, December 2016 i ii Table of Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Research questions 4 Thesis structure 6 Chapter 1: Theoretical frameworks 9 Theories of miniaturisation 13 Semiotics of miniaturisation 17 Elements of miniaturisation 21 Mimesis 22 Scaling 27 Simplification 31 Miniatures in circulation 34 Authenticity and Northwest Coast art 37 Summary 42 Chapter 2: Methodology 43 Museum ethnography 44 Documentary research 51 Indigenous ethnography 53 Assessment of fieldwork 64 Summary 73 Chapter 3: The Northwest Coast 75 History 75 Peoples 81 Social structures 84 Environment 86 iii Material Culture 90 Material culture typologies 95 Summary 104 Chapter 4: Pedagogy and process: Miniaturisation among the Makah 105 The Makah 107 Whaling 109 Nineteenth-century miniaturisation 113 Commercial imperatives 117 Cultural continuity and the Makah 121 Analysing Makah miniatures 123 Miniatures as pedagogical and communicative actors 129 Chapter 5: The Haida string: -

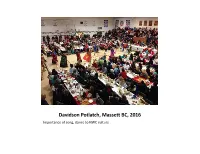

Class 5 Haida

Davidson Potlatch, Massett BC, 2016 Importance of song, dance to NWC culture Today Next Tuesday’s visit to the Canadian Museum of History Haida Art The Great Box Project Haida Gwaii: Graham Island & Moresby Island Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, Skidegate, Masset, Rose Point (NE corner) Formline elements in Northern NWC art Taken from Hilary Stewart’s book, Looking at Northwest Coast Indian Art, 1979 Thunderbird Ovoids Tension – top edge is sprung upwards as though from pressure, lower edge bulges up caused by downward & inward pull of 2 lower corners. Shape varies. Used as head of creature or human, eye socket, major joints, wing shape, tail, fluke or fin. Small ovoids: for faces, ears, to fill empty spaces & corners. U-forms & S-forms Large U-forms used as: body of bird or animal and feathers Small: fill in open spaces. Kwakwaka’wakw use for small feathers S-forms: part of leg or arm or outline or ribcage Split U-forms Bill Reid, Haida Dogfish See: Strong form line, U forms, split U forms, ovoids compressed into circles Also crescents, teeth, tri-negs… Diverse eyes with eyelids Both eyeball and eyelid are usually placed within an ovoid representing the socket From top to bottom: nose variations, animal ears, eyebrows, tongues, protruding tongues Frontal and profile faces, hands Nose – usually broad & flaring. Ears – U form on top sides of head (humans – no ears). Hands – graceful, stemming from ovoid. Also a symbol for hand-crafted. Claws, legs, feet, arms Hands, flippers & claws usually substantial but arms & legs are often minimal and difficult to locate. -

Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Ph.D. [email protected]

Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Ph.D. [email protected] Education Ph.D. 2007 Art History, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington Dissertation: Precious Metals: Silver and Gold Bracelets from the Northwest Coast M.A. 1998 Art History, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington B.A. 1993 Middlebury College, Vermont Professional Appointments 2016-present Assistant Professor, Art History, School of Art + Art History + Design, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 2016-present Curator of Northwest Native Art, Burke Museum, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 2016-present Director, Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art, Burke Museum, Seattle, WA 2015 Associate Director, Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art, Burke Museum, Seattle, WA 2010-2015 Assistant Director and Managing Editor, Bill Holm Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art, Burke Museum, Seattle, WA 2012-2015 Visiting Lecturer, American Indian Studies Department, University of Washington 2008-2015 Visiting Lecturer, Division of Art History, University of Washington 2008-2009 Managing Editor for Bill Holm Center Publications, Burke Museum 2004-2005 Visiting Instructor, Division of Art History, University of Washington 2003-2004 Curatorial Assistant, Burke Museum, University of Washington 2003 Winter Term Instructor, Middlebury College, Middlebury, VT 2002 Research Assistant, Burke Museum, University of Washington 2000-2001 Visiting Lecturer, South Seattle Community College, Seattle, WA 1997-2001 Teaching Assistant, Division of Art History, University -

Iljuwas Bill Reid

ART CANADA INSTITUTE INSTITUT DE L’ART CANADIEN CATALYST FOR CHANGE ILJUWAS BILL REID Few twentieth-century artists have been catalysts for the reclamation of a culture. In the ACI’s new art book Iljuwas Bill Reid: Life & Work, the celebrated curator and scholar Gerald McMaster makes it clear that the iconic Northwest Coast creator was one of them. Bill Reid watching memorial pole being raised in the Haida Village, 1962 This year marks the centenary of the birth of Iljuwas Bill Reid (1920–1998), one of the most ground-breaking artists in the history of our country. Although Reid’s mother was Haida, he grew up knowing little about the culture because the Indian Act denied him his heritage. Yet, overcoming adversity, Reid went on to become a leader in Northwest Coast art. His influence was unprecedented and his name was publicly confirmed by the Haida community as Iljuwas (Princely One or Manly One). Today, the Art Canada Institute proudly publishes Iljuwas Bill Reid: Life & Work, which joins our open-access digital library of books on artists who have transformed the cultural landscape. Its author, the acclaimed curator and scholar Gerald McMaster, reveals how, during Reid’s fifty-year-long career, the artist innovatively adapted Haida worldviews to the times in which he lived, creating a body of work whose legacy is a complex story of power, resilience, and strength. To celebrate this important publication, here are ten topics drawn from it that explore how Reid lived the reality of colonialism yet tenaciously forged a practice that honoured Haida ways of seeing. -

Bassnett, Susan. “When Is a Translation Not a Translation?”

Preliminary Bibliography Abley, Mark. "At Last, Canada's Natives Find Voices on the Page." The Gazette 23 Feb. 1991. Adams, Dawn, ed. The Queen Charlotte Islands Reading Series. Curriculum Resource materials. The Queen Charlotte Islands Reading Series. Vancouver: WEDGE, Faculty of Education, University of B.C, 1983-1985. Adams, Howard. A Tortured People: The Politics of Colonization. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books, 1995. Alcoff, Linda. "The Problem of Speaking for Others." Cultural Critique 20.Winter (1991- 1992): 5-32. Allen, Lillian. "Transforming the Cultural Fortress: Setting the Agenda for Anti-Racism Work in Culture." Parallelogramme 19.3 (1993-1994): 48-59. Andersen, Doris. Slave of the Haida. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1974. Armstrong, Jeannette. "The Disempowerment of First North American Native Peoples and Empowerment Through Their Writing." An Anthology of Canadian Native Literature in English. Eds. Daniel David Moses and Terry Goldie. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1992. 207-11. ---. "Editor's Note." Looking At the Words of Our People. Armstrong, ed. 7-8. ---. Looking At the Words of Our People: First Nations Analysis of Literature. Penticton, BC: Theytus Books , 1993. Baele, Nancy. "Everyone's in the Same Boat; Haida Spirit Canoe Provides Some Inescapable Truths." The Ottawa Citizen 3 Nov. 1991: C.2. Baker, Marie Annharte. “Dis Mischief: Give It Back Before I Remember I Gave It Away." Vol. 28. 1994. 204-13. Balkind, Alvin, and Robert Bringhurst. Visions: Contemporary Art in Canada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1983. Bannerji, Himani ed. Returning the Gaze: Essays on Racism, Feminism and Politics. Toronto: Sister Vision, 1993. Barbeau, Marius. Haida Carvers in Argillite. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada, 1974.