He Trusted the People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

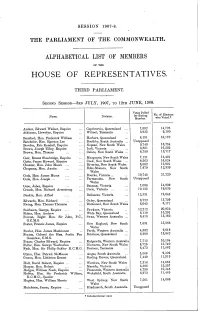

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

How Federal Theory Supports States' Rights Michelle Evans

The Western Australian Jurist Vol. 1, 2010 RETHINKING THE FEDERAL BALANCE: HOW FEDERAL THEORY SUPPORTS STATES’ RIGHTS MICHELLE EVANS* Abstract Existing judicial and academic debates about the federal balance have their basis in theories of constitutional interpretation, in particular literalism and intentionalism (originalism). This paper seeks to examine the federal balance in a new light, by looking beyond these theories of constitutional interpretation to federal theory itself. An examination of federal theory highlights that in a federal system, the States must retain their powers and independence as much as possible, and must be, at the very least, on an equal footing with the central (Commonwealth) government, whose powers should be limited. Whilst this material lends support to intentionalism as a preferred method of constitutional interpretation, the focus of this paper is not on the current debate of whether literalism, intentionalism or the living constitution method of interpretation should be preferred, but seeks to place Australian federalism within the broader context of federal theory and how it should be applied to protect the Constitution as a federal document. Although federal theory is embedded in the text and structure of the Constitution itself, the High Court‟s generous interpretation of Commonwealth powers post-Engineers has led to increased centralisation to the detriment of the States. The result is that the Australian system of government has become less than a true federation. I INTRODUCTION Within Australia, federalism has been under attack. The Commonwealth has been using its financial powers and increased legislative power to intervene in areas of State responsibility. Centralism appears to be the order of the day.1 Today the Federal landscape looks very different to how it looked when the Australian Colonies originally „agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth‟2, commencing from 1 January 1901. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

The Governor–General

CHAPTER V THE GOVERNOR-GENERALO, A MOST punctilious, prompt and copious correspondent was Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson, who presided over the Govern- ment of the Commonwealth from 1914 to 1920. His tall. perpendicular script was familiar to a host of friends in many countries, and his official letters to His Majesty the King and the four Secretaries of State during his period-Mr. Lewis Harcourt, Mr. Walter Long,2 Mr. Bonar Law3 and Lord hlilner'-would, if printed, fill several substantial volumes. His habit was to write even the longest letters with his own hand, for he had served his apprenticeship to official life in the Foreign Office at a period when the typewriter was still a new-fangled invention. He rarely dictated correspondence, but he kept typed copies of all important letters, and, being bq nature and training extremely orderly, filed them in classified, docketed packets. He was disturbed if a paper got out of its proper place. He wrote to Sir John Quick! part author oi Quick and Garran's well-known commentary on the Com- monwealth Constitution, warning him that the documents relating to the double dissolution, printed as a parliamentary paper on the 8th of October, 1914, were arranged in the wrong order. Such a fault, or anything like slovenliness or negligence in the transaction and record of official business, brought forth a gentle, but quite significant, reproof. In respect to business method, the Governor-General was one of the best trained public servants in the Commonwealth during the war years. - - 'This chapter is based upon the Novar papers at Raith. -

COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT Ca Paper Prepared by Sir John Kirwan and Read to the IVA

6 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Tke First COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT cA Paper prepared by Sir john Kirwan and read to the IVA. Historical Soci'ely on 27tlt September, /946. HE first Prime Minister of Australia, the Smith, Alexander Percival Matheson, George Right Honourable Sir Edmund Barton, Pearce, Hugh de Largie, Edward Harney and T formed his Government on 1st January, Norman Ewing. Senator Ewing resigned 1901. By that time the Commonwealth Con from the Senate in April, 1903, and H. J. stitution had been accepted by the votes of Saunders wa selected to fill the vacancy at a majority of the electors in all the six a joint sitting of the State Parliament- colonies, the Imperial Parliament had passed the necessary legislation and the essential Of these eleven members, Sir John Forrest proclamation had been signed by Her was the only one with notable or extended Majesty, Queen Victoria. parliamentary experience. He already had a distinguished career as an explorer, also he The result of the referendum, in West had worthily filled various public offices and Australia was 44,BOO in favour of federal had been Premier for more than ten years. union and 19,691 against, the majority being Of the others, Mr. Solomon and Mr. Ewing more than two to one, Perth and Fremantle had sat for some years in the Legislative gave substantial majorities for federation and Assembly and Mr. Saunders in the Legisla on the Goldfields the Yes vote was 15 to one. tive Council. Staniforth Smith at the time of his election for the Senate, was Mayor of I had taken a prominent part in further Kalgoorlie. -

The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Harry Hobbs and Andrew Trotter* THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE: MAKING SENSE OF MULTIPLE INTENTIONS ABSTRACT The delegates to the 1890s Constitutional Conventions were well aware that the amendment mechanism is the ‘most important part of a Cons titution’, for on it ‘depends the question as to whether the state shall develop with peaceful continuity or shall suffer alternations of stagnation, retrogression, and revolution’.1 However, with only 8 of 44 proposed amendments passed in the 116 years since Federation, many commen tators have questioned whether the compromises struck by the delegates are working as intended, and others have offered proposals to amend the amending provision. This paper adds to this literature by examining in detail the evolution of s 128 of the Constitution — both during the drafting and beyond. This analysis illustrates that s 128 is caught between three competing ideologies: representative and respons ible government, popular democracy, and federalism. Understanding these multiple intentions and the delicate compromises struck by the delegates reveals the origins of s 128, facilitates a broader understanding of colonial politics and federation history, and is relevant to understanding the history of referenda as well as considerations for the section’s reform. I INTRODUCTION ver the last several years, three major issues confronting Australia’s public law framework and a fourth significant issue concerning Australia’s commitment Oto liberalism and equality have been debated, but at an institutional level progress in all four has been blocked. The constitutionality of federal grants to local government remains unresolved, momentum for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution ebbs and flows, and the prospects for marriage equality and an * Harry Hobbs is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law, Lionel Murphy postgraduate scholar, and recipient of the Sir Anthony Mason PhD Award in Public Law. -

Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896)

Papers on Parliament No. 32 SPECIAL ISSUE December 1998 The People’s Conventions: Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896) Editors of this issue: David Headon (Director, Centre for Australian Cultural Studies, Canberra) Jeff Brownrigg (National Film and Sound Archive) _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1998 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Copy editor for this issue: Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3078 Email: [email protected] ISSN 1031–976X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Centre for Australian Cultural Studies The Corowa and District Historical Society Charles Sturt University (Bathurst) The Bathurst District Historical Society Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Introduction When Henry Parkes delivered his Tenterfield speech in October 1889, declaring federation’s time had come, he provided the stimulus for an eighteen-month period of lively speculation. Nationhood, it seemed, was in the air. The 1890 Australian Federation Conference in Melbourne, followed by the 1891 National Australasian Convention in Sydney, appeared to confirm genuine interest in the national cause. Yet the Melbourne and Sydney meetings brought together only politicians and those who might be politicians. These were meetings, held in the Australian continent’s two most influential cities, which only succeeded in registering the aims and ambitions of a very narrow section of the colonial population. In the months following Sydney’s Convention, the momentum of the official movement was dissipated as the big strikes and severe depression engulfed the colonies. -

The Constitution Makers

Papers on Parliament No. 30 November 1997 The Constitution Makers _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1997 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Editors of this issue: Kathleen Dermody and Kay Walsh. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3078 ISSN 1031–976X Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Cover illustration: The federal badge, Town and Country Journal, 28 May 1898, p. 14. Contents 1. Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies 1 The Hon. John Bannon 2. A Federal Commonwealth, an Australian Citizenship 19 Professor Stuart Macintyre 3. The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention 33 Professor Geoffrey Bolton 4. Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—the Senate’s First Republican 49 Dr Mark McKenna 5. The High Court and the Founders: an Unfaithful Servant 63 Professor Greg Craven 6. The 1897 Federal Convention Election: a Success or Failure? 93 Dr Kathleen Dermody 7. Federation Through the Eyes of a South Australian Model Parliament 121 Derek Drinkwater iii Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies Towards Federation: the Role of the Smaller Colonies* John Bannon s we approach the centenary of the establishment of our nation a number of fundamental Aquestions, not the least of which is whether we should become a republic, are under active debate. But after nearly one hundred years of experience there are some who believe that the most important question is whether our federal system is working and what changes if any should be made to it. -

The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949)

‘Mightier than the Sword’: The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) By Anne Partlon MA (Eng) and Grad. Dip. Ed This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2011 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ............................................................... Anne Partlon ii Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction: A Most Unsuitable Candidate 1 Chapter 1:The Kirwans of Woodfield 14 Chapter 2:‘Bound for South Australia’ 29 Chapter 3: ‘Westward Ho’ 56 Chapter 4: ‘How the West was Won’ 72 Chapter 5: The Honorable Member for Kalgoorlie 100 Chapter 6: The Great Train Robbery 120 Chapter 7: Changes 149 Chapter 8: War and Peace 178 Chapter 9: Epilogue: Last Post 214 Conclusion 231 Bibliography 238 iii Abstract John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) played a pivotal role in the Australian Federal movement. At a time when the Premier of Western Australia Sir John Forrest had begun to doubt the wisdom of his resource rich but under-developed colony joining the emerging Commonwealth, Kirwan conspired with Perth Federalists, Walter James and George Leake, to force Forrest’s hand. Editor and part- owner of the influential Kalgoorlie Miner, the ‘pocket-handkerchief’ newspaper he had transformed into one of the most powerful journals in the colony, he waged a virulent press campaign against the besieged Premier, mocking and belittling him at every turn and encouraging his east coast colleagues to follow suit. -

GETTING IT TOGETHER from Colonies to Federation

GETTING IT TOGETHER From Colonies to Federation victoria People and Places INvEStIGATIoNS oF aUSTRALIa’S JoUrNEYInvestigations of Australia’s journey TO NATIoNHOOD FOR tHE MIDDLE to nationhood for the middle years classroom YEARS cLaSSROOM GETTING IT TOGETHER vIctorIa – PEoPLE aND PLACES © COMMoNWEaLtH oF aUSTRALIa i Getting It Together: From Colonies to Federation has been funded by the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Getting It Together: From Colonies to Federation – Victoria ISBN: 978 1 74200 096 1 SCIS order number: 1427626 Full bibliographic details are available from Curriculum Corporation. PO Box 177 Carlton South Vic 3053 Australia Tel: (03) 9207 9600 Fax: (03) 9910 9800 Email: [email protected] Website: www.curriculum.edu.au Published by the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House PO Box 7088 Canberra BC ACT 2610 Tel: (02) 6270 8222 Fax: (02) 6270 8111 www.moadoph.gov.au September 2009 © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at www.ag.gov.au/cca This work is available for download from the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House: http://moadoph.gov.au/learning/resources-and-outreach Edited by Katharine Sturak and Zoe Naughten Designed by Deanna Vener GETTING IT TOGETHER vIctorIa – PEoPLE aND PLACES © COMMoNWEaLtH oF aUSTRALIa People and Places The colony of Victoria, like Queensland, was named after Queen Victoria. -

1115-Sir John Quick - He Trusted the People (Inaugural Quick Lecture).Pdf

LA TROBE UNIVERSITY BENDIGO CAMPUS Friday 29 April 1994 ~;L!: :HElW\U(}UFlALJ'fiolAUGURAL SIR JOHN QUICK BENDIGO PUBLIC LECTURE "-.<' . SIR JOHN OUICK - HE TRUSTED THE PEOPLE The Hon Michael Kirby AC CMG* -A FATHER OF THE FEDERATION "Itis customary, in a public lecture dedicated to the memory of a named 'Xf:'" p~g~"\i!1, to say something of that person's life. In an inaugural lecture, it is , "~~':" . jl~lJg*Ory. .i~;C: ~bSir John Quick was born in Cornwall, England in 1852. With his family :lf~~3JIleh£,",mle to Australia, arriving in Bendigo in 1854, then in the midst of the gold :j-~;"2' :~_, \;i)1§~;,•.His His father died soon afterwards so that, at an early age, he was cast upon ~®'\\~-"-- !i!{own talents: and great they were. :~~;ii~·-·. ,,;::;;':'; , {i~{,: .;; His formal education at the local public school finished when the young f\.~~:·': '!gllllwas... was but 10 years of age. He then went out to work in an iron foundry and l't~;\ '}tter. a newspaper printing room. From there he graduated to be a junior ;'t':.< .',- ~;~~;~t~polrtert::.;{ti.Etporter on the Bendigo Independent. His expert shorthand soon secured him a ~;N~~~~With. with the Melbourne Age. Supported by a scholarship, he matriculated to I '~f~~~' W~iive:rsiltyJiiiversity of Melbourne, graduating with Bachelor of Laws in 1877 and n!boctorD1oct,or of Laws in 1882. ,{c.' )~y!·: His unflagging energy took him into the Victorian Legislative Assembly :,~Y::' ;Mbnber\!ielnbt:r for SandburstSandhurst (Bendigo) in 1880. Upon his election, he resigned .":~~:'; '~dKthe Age and opened a practice as a solicitor in Bendigo.