Australian Constitutionalism Between Subsidiarity and Federalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Negative Implications in the Interpretation of Commonwealth Legislative Powers

THE ROLE OF NEGATIVE IMPLICATIONS IN THE INTERPRETATION OF COMMONWEALTH LEGISLATIVE POWERS MICHAEL STOKES* One of the bases for the view that Commonwealth powers should be interpreted broadly is the idea that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power. The paper argues that far from being wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power it is necessary to do so in that it is impossible to interpret such grants sensibly without drawing negative implications from them. This paper considers Isaacs J’s argument in Huddart Parker that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power, as it is the most detailed defence of that position, and the adoption of similar arguments in Work Choices. It then considers the merits of Isaacs J’s argument, rejecting it because it is impossible to interpret positive grants of power without drawing negative implications from them in any context and in the Australian constitutional context in particular. This paper looks at how the scope of such implications is to be determined and how constitutional grants of power ought to be interpreted in the light of negative implications. It concludes that it is possible to determine the scope of the negative implications implicit in the s 51 grants of power and to interpret those powers in the light of the implications while accepting that state powers are residual and that their content cannot be determined until the content of all Commonwealth powers is known. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 176 II The Origin of the Argument That It Is Wrong to Draw Negative Implications from Positive Grants of Power ....................................................... -

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: a Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon*

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: A Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon* The essential and distinctive feature of “a truly federal government” is the preservation of the separate existence and corporate life of each of the component States concurrently with that of the national government. Accepting that a number of polities are contemplated as coexisting within a federation does not, however, address the fundamental question of how legislative and executive powers are to be allocated among the constituent constitutional units inter se, nor the extent to which the various polities are immune from interference occasioned by their constitutional counterparts. These “federal” questions are fundamental as they ultimately define the prism through which one views the Constitution. Shifts in the lens have resulted in significant ramifications for intergovernmental relations. This article traces the development of the Melbourne Corporation doctrine in Australia, and undertakes a comparative analysis with the development of the cognate jurisprudence in the United States. Analysis is undertaken of the major Australian industrial relations decisions, such as the Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria, Queensland Electricity Commission v Commonwealth, and United Firefighters Union of Australia v Country Fire Authority, in this context. But one of the first and most leading principles on which the commonwealth and the laws are consecrated, is left the temporary possessors -

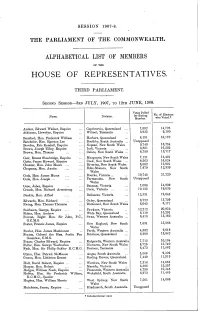

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

How Federal Theory Supports States' Rights Michelle Evans

The Western Australian Jurist Vol. 1, 2010 RETHINKING THE FEDERAL BALANCE: HOW FEDERAL THEORY SUPPORTS STATES’ RIGHTS MICHELLE EVANS* Abstract Existing judicial and academic debates about the federal balance have their basis in theories of constitutional interpretation, in particular literalism and intentionalism (originalism). This paper seeks to examine the federal balance in a new light, by looking beyond these theories of constitutional interpretation to federal theory itself. An examination of federal theory highlights that in a federal system, the States must retain their powers and independence as much as possible, and must be, at the very least, on an equal footing with the central (Commonwealth) government, whose powers should be limited. Whilst this material lends support to intentionalism as a preferred method of constitutional interpretation, the focus of this paper is not on the current debate of whether literalism, intentionalism or the living constitution method of interpretation should be preferred, but seeks to place Australian federalism within the broader context of federal theory and how it should be applied to protect the Constitution as a federal document. Although federal theory is embedded in the text and structure of the Constitution itself, the High Court‟s generous interpretation of Commonwealth powers post-Engineers has led to increased centralisation to the detriment of the States. The result is that the Australian system of government has become less than a true federation. I INTRODUCTION Within Australia, federalism has been under attack. The Commonwealth has been using its financial powers and increased legislative power to intervene in areas of State responsibility. Centralism appears to be the order of the day.1 Today the Federal landscape looks very different to how it looked when the Australian Colonies originally „agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth‟2, commencing from 1 January 1901. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

The Governor–General

CHAPTER V THE GOVERNOR-GENERALO, A MOST punctilious, prompt and copious correspondent was Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson, who presided over the Govern- ment of the Commonwealth from 1914 to 1920. His tall. perpendicular script was familiar to a host of friends in many countries, and his official letters to His Majesty the King and the four Secretaries of State during his period-Mr. Lewis Harcourt, Mr. Walter Long,2 Mr. Bonar Law3 and Lord hlilner'-would, if printed, fill several substantial volumes. His habit was to write even the longest letters with his own hand, for he had served his apprenticeship to official life in the Foreign Office at a period when the typewriter was still a new-fangled invention. He rarely dictated correspondence, but he kept typed copies of all important letters, and, being bq nature and training extremely orderly, filed them in classified, docketed packets. He was disturbed if a paper got out of its proper place. He wrote to Sir John Quick! part author oi Quick and Garran's well-known commentary on the Com- monwealth Constitution, warning him that the documents relating to the double dissolution, printed as a parliamentary paper on the 8th of October, 1914, were arranged in the wrong order. Such a fault, or anything like slovenliness or negligence in the transaction and record of official business, brought forth a gentle, but quite significant, reproof. In respect to business method, the Governor-General was one of the best trained public servants in the Commonwealth during the war years. - - 'This chapter is based upon the Novar papers at Raith. -

Chapter One the Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case

Chapter One The Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case Professor Geoffrey de Q Walker Holding the balance: 1903 to 1920 The High Court of Australia’s 1920 decision in the Engineers’ Case1 remains an event of capital importance in Australian history. It is crucial not so much for what it actually decided as for the way in which it switched the entire enterprise of Australian federalism onto a diverging track, that carried it to destinations far removed from those intended by the generation that had brought the Federation into being. Holistic beginnings. How constitutional doctrine developed through the Court’s decisions from 1903 to 1920 has been fully described elsewhere, including in a paper presented at the 1995 conference of this society by John Nethercote.2 Briefly, the original Court comprised Chief Justice Griffith and Justices Barton and O’Connor, who had been leaders in the federation movement and authors of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution. The starting-point of their adjudicative philosophy was the nature of the Constitution as an enduring instrument of government, not merely a British statute: “The Constitution Act is not only an Act of the Imperial legislature, but it embodies a compact entered into between the six Australian colonies which formed the Commonwealth. This is recited in the Preamble to the Act itself”.3 Noting that before Federation the Colonies had almost unlimited powers,4 the Court declared that: “In considering the respective powers of the Commonwealth and the States it is essential to bear in mind that each is, within the ambit of its authority, a sovereign State”.5 The founders had considered Canada’s constitutional structure too centralist,6 and had deliberately chosen the more decentralized distribution of powers used in the Constitution of the United States. -

Sumptuary Law by Any Other Name: Manifestations of Sumptuary Regulation in Australia, 1901-1927

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Sumptuary law by any other name: manifestations of sumptuary regulation in Australia, 1901-1927 Caroline Irene Dick University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Dick, Caroline Irene, Sumptuary law by any other name: manifestations of sumptuary regulation in Australia, 1901-1927, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Law, Humanities, and the Arts, University of Wollongong, 2015. -

COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT Ca Paper Prepared by Sir John Kirwan and Read to the IVA

6 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Tke First COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT cA Paper prepared by Sir john Kirwan and read to the IVA. Historical Soci'ely on 27tlt September, /946. HE first Prime Minister of Australia, the Smith, Alexander Percival Matheson, George Right Honourable Sir Edmund Barton, Pearce, Hugh de Largie, Edward Harney and T formed his Government on 1st January, Norman Ewing. Senator Ewing resigned 1901. By that time the Commonwealth Con from the Senate in April, 1903, and H. J. stitution had been accepted by the votes of Saunders wa selected to fill the vacancy at a majority of the electors in all the six a joint sitting of the State Parliament- colonies, the Imperial Parliament had passed the necessary legislation and the essential Of these eleven members, Sir John Forrest proclamation had been signed by Her was the only one with notable or extended Majesty, Queen Victoria. parliamentary experience. He already had a distinguished career as an explorer, also he The result of the referendum, in West had worthily filled various public offices and Australia was 44,BOO in favour of federal had been Premier for more than ten years. union and 19,691 against, the majority being Of the others, Mr. Solomon and Mr. Ewing more than two to one, Perth and Fremantle had sat for some years in the Legislative gave substantial majorities for federation and Assembly and Mr. Saunders in the Legisla on the Goldfields the Yes vote was 15 to one. tive Council. Staniforth Smith at the time of his election for the Senate, was Mayor of I had taken a prominent part in further Kalgoorlie. -

The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Harry Hobbs and Andrew Trotter* THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE: MAKING SENSE OF MULTIPLE INTENTIONS ABSTRACT The delegates to the 1890s Constitutional Conventions were well aware that the amendment mechanism is the ‘most important part of a Cons titution’, for on it ‘depends the question as to whether the state shall develop with peaceful continuity or shall suffer alternations of stagnation, retrogression, and revolution’.1 However, with only 8 of 44 proposed amendments passed in the 116 years since Federation, many commen tators have questioned whether the compromises struck by the delegates are working as intended, and others have offered proposals to amend the amending provision. This paper adds to this literature by examining in detail the evolution of s 128 of the Constitution — both during the drafting and beyond. This analysis illustrates that s 128 is caught between three competing ideologies: representative and respons ible government, popular democracy, and federalism. Understanding these multiple intentions and the delicate compromises struck by the delegates reveals the origins of s 128, facilitates a broader understanding of colonial politics and federation history, and is relevant to understanding the history of referenda as well as considerations for the section’s reform. I INTRODUCTION ver the last several years, three major issues confronting Australia’s public law framework and a fourth significant issue concerning Australia’s commitment Oto liberalism and equality have been debated, but at an institutional level progress in all four has been blocked. The constitutionality of federal grants to local government remains unresolved, momentum for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution ebbs and flows, and the prospects for marriage equality and an * Harry Hobbs is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law, Lionel Murphy postgraduate scholar, and recipient of the Sir Anthony Mason PhD Award in Public Law. -

Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896)

Papers on Parliament No. 32 SPECIAL ISSUE December 1998 The People’s Conventions: Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896) Editors of this issue: David Headon (Director, Centre for Australian Cultural Studies, Canberra) Jeff Brownrigg (National Film and Sound Archive) _________________________________ Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published 1998 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Copy editor for this issue: Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3078 Email: [email protected] ISSN 1031–976X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Centre for Australian Cultural Studies The Corowa and District Historical Society Charles Sturt University (Bathurst) The Bathurst District Historical Society Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Introduction When Henry Parkes delivered his Tenterfield speech in October 1889, declaring federation’s time had come, he provided the stimulus for an eighteen-month period of lively speculation. Nationhood, it seemed, was in the air. The 1890 Australian Federation Conference in Melbourne, followed by the 1891 National Australasian Convention in Sydney, appeared to confirm genuine interest in the national cause. Yet the Melbourne and Sydney meetings brought together only politicians and those who might be politicians. These were meetings, held in the Australian continent’s two most influential cities, which only succeeded in registering the aims and ambitions of a very narrow section of the colonial population. In the months following Sydney’s Convention, the momentum of the official movement was dissipated as the big strikes and severe depression engulfed the colonies.