The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

MEDIA RELEASE 7 February 2017 Premier awards Tennyson Medal at SACE Merit Ceremony The Premier of South Australia, the Hon. Jay Weatherill MP, awarded the prestigious Tennyson Medal for excellence in English Studies to 2016 Year 12 graduate, Ashleigh Jones at the SACE Merit Ceremony at Government House today. The ceremony, in its twenty-ninth year, saw 996 students awarded with 1302 subject merits for outstanding achievement in SACE Stage 2 subjects. Subject merits are awarded to students who gain an overall subject grade of A+ and demonstrate exceptional achievement in that subject. As part of the Merit Ceremony, His Excellency the Hon. Hieu Van Le AC, the Governor of South Australia, presented the following awards: Governor of South Australia Commendation for outstanding overall achievement in the SACE (twenty-five recipients in 2016) Governor of South Australia Commendation — Aboriginal Student SACE Award for the Aboriginal student with the highest overall achievement in the SACE Governor of South Australia Commendation – Excellence in Modified SACE Award for the student with an identified intellectual disability who demonstrates outstanding achievement exclusively through SACE modified subjects. The Tennyson Medal dates back to 1901 when the former Governor of South Australia, Lord Tennyson, established the Tennyson Medal to encourage the study of English literature. The long list of recipients includes the late John Bannon AO, 39th Premier of South Australia, who was awarded the medal in 1961. For her Year 12 English Studies, Ashleigh studied works by Henrik Ibsen (A Doll’s House), Zhang Yimou who directed Raise the Red Lantern, and Tennessee Williams (The Glass Menagerie). -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

JHSSA Index 2014

Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Subject Index 1975-2014 Nos 1 to 42 Compiled by Brian Samuels The Historical Society of South Australia Inc PO Box 519 Kent Town 5071 South Australia JHSSA Subject Index 1975–2014 page 35 Subject Index 1975-2014: Nos 1 to 42 This index consolidates and updates the Subject Index to the Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Nos 1 - 20 (1974 [sic] - 1992) which appeared in the 1993 Journal and its successors for Nos 21 - 25 (1998 Journal) and 26 - 30 (2003 Journal). In the latter index new headings for Gardens, Forestry, Place Names and Utilities were added and some associated reindexing of the entire index database was therefore undertaken. The indexing of a few other entries was also improved, as has occurred with this latest updating, in which Heritage Conservation and Imperial Relations are new headings while Death Rituals has been subsumed into Folklife. The index has certain limitations of design. It uses a limited number of, and in many instances relatively broad, subject headings. It indexes only the main subjects of each article, judged primarily from the title, and does not index the contents – although Biography and Places have subheadings. Authors and titles are not separately indexed, but they do comprise separate fields in the index database. Hence author and title indexes could be included in future published indexes if required. Titles are cited as they appear at the head of each article. Occasionally a note in square brackets has been added to clarify or amplify a title. -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

Perth Strike 1897

1 William H ‘Bill’ Mellor and the Perth- Fremantle building trades strikes of 1896-97 11,598 words/ 16,890 with notes When Bill Mellor lost his footing on a ten-metre scaffold in 1897, that misstep cost him his life, his wife and three children their provider, the Builders’ Labourers’ Society in Western Australia its most energetic official, and socialism a champion. On Thursday, 11 June, the 35-year old Mellor had been working on the Commercial Union Assurance offices on St Georges Terrace when he tumbled backwards, breaking his back, to die in hospital a few hours later.1 In the days that followed, the labour movement rallied to support Mellor’s family. Bakers, boot-makers, printers and tailors sent subscription lists around their workplaces;2 the donations from twenty building jobs totaled £174 9s 4d, while Mellor’s employer and associates contributed £50.3 The Kalgoorlie and Boulder Workers Association forwarded their collections with notes of appreciation for Mellor’s organising in Melbourne and Sydney.4 The Perth and Fremantle Councils provided their Town Halls without charge for benefit concerts.5 The Relief Fund realised £45 from the sale of Mellor’s house and allotment, in Burt Street, Forrest Hill, a housing estate in North Perth.6 The Fund’s trustees paid out £15 on the funeral, to which a florist donated wreaths,7 while a further 1 West Australian (WA), 10 June 1897, p. 4; the building opened in December, WA, 2 December 1897, p. 3. 2 WA, 29 June 1897, p. 4, 6 July 1897, p. -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915

5 Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915. Andrew Fisher became the 5th prime minister when the Liberal- Labor coalition government headed by Alfred Deakin collapsed due to loss of parliamentary Labor support. Fisher’s first period as prime minister ended when the new Fusion Party of Deakin and Joseph Cook defeated the government in parliament. His second term resulted from an overwhelming Labor victory at elections in 1910. However, Labor lost power by one seat at the 1913 elections. Fisher was prime minister again in 1914, as a result of a double-dissolution election. Fisher resigned from office in October 1915, his health affected by the pressures of political life. Member of the Australian Labor Party c1901-28. Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Wide Bay (Queensland) 1901-15; Minister for Trade and Customs 1904; Treasurer 1908-09, 1910-13, 1914-15. Main achievements (1904-1915) Under his prime ministership, the Commonwealth Government issued its first currency which replaced bank and State currency as the only legal tender. Also, the Commonwealth Bank was established. Strengthened the Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Introduced a progressive land tax on unimproved properties. Construction began on the trans-Australian railway, linking Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. Established the Australian Capital Territory and brought the Northern Territory under Commonwealth control. Established the Royal Australian Navy. Improved access to invalid and aged pensions and brought in maternity allowances. Introduced workers’ compensation for federal public servants. -

Yet We Are Told That Australians Do Not Sympathise with Ireland’

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ‘Yet we are told that Australians do not sympathise with Ireland’ A study of South Australian support for Irish Home Rule, 1883 to 1912 Fidelma E. M. Breen This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Research in the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. September 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 4 Declaration ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 6 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 WHAT WAS THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT? ................................................................. 17 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE .................................................................................... -

Anarchism in Australia

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism in Australia Bob James Bob James Anarchism in Australia 2009 James, Bob. “Anarchism, Australia.” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present, edited by Immanuel Ness, 105–108. Vol. 1. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Gale eBooks (accessed June 22, 2021). usa.anarchistlibraries.net 2009 James, B. (Ed.) (1983) What is Communism? And Other Essays by JA Andrews. Prahran, Victoria: Libertarian Resources/ Backyard Press. James, B. (Ed.) (1986) Anarchism in Australia – An Anthology. Prepared for the Australian Anarchist Centennial Celebra- tion, Melbourne, May 1–4, in a limited edition. Melbourne: Bob James. James, B. (1986) Anarchism and State Violence in Sydney and Melbourne, 1886–1896. Melbourne: Bob James. Lane, E. (Jack Cade) (1939) Dawn to Dusk. N. P. William Brooks. Lane, W. (J. Miller) (1891/1980) Working Mans’Paradise. Syd- ney: Sydney University Press. 11 Legal Service and the Free Store movement; Digger, Living Day- lights, and Nation Review were important magazines to emerge from the ferment. With the major events of the 1960s and 1970s so heavily in- fluenced by overseas anarchists, local libertarians, in addition Contents to those mentioned, were able to generate sufficient strength “down under” to again attempt broad-scale, formal organiza- tion. In particular, Andrew Giles-Peters, an academic at La References And Suggested Readings . 10 Trobe University (Melbourne) fought to have local anarchists come to serious grips with Bakunin and Marxist politics within a Federation of Australian Anarchists format which produced a series of documents. Annual conferences that he, Brian Laver, Drew Hutton, and others organized in the early 1970s were sometimes disrupted by Spontaneists, including Peter McGre- gor, who went on to become a one-man team stirring many national and international issues. -

John Christian WATSON Prime Minister 27 April to 17 August 1904

3 John Christian WATSON Prime Minister 27 April to 17 August 1904 Chris Watson became the 3rd Prime Minister when the government of Alfred Deakin, a Protectionist, fell due to Labor’s refusal to support the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. Member of Australian Labor Party 1900-16; Nationalist Party 1917-c1922. Member for Bland (NSW) in House of Representatives 1901-06 and for South Sydney 1906-10. Treasurer 1904. Prior to 1901 he was the Member for Young in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1894-1901. Watson was replaced as prime minister by George Reid, of the Free Trade Party, when Labor’s amended Conciliation and Arbitration Bill failed to win support in parliament. Watson resigned after unsuccessfully seeking a double dissolution election. Main achievements (1904) Headed the world’s first national Labor government. The main achievement of Watson’s prime ministership was the advancement of the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, which was eventually passed in December 1904 under the Reid government. Personal life Born 9 April 1867, Valparaiso, Chile, son of Johan Christian Tanck and his wife Martha. Became Watson when Martha remarried in 1869. Reared in New Zealand. Died 18 November, 1941, Sydney. Limited formal education in New Zealand. Worked as nipper on railway construction at age of ten and on father’s farm. Became a compositor with New Zealand newspapers, active in the union, and migrated to Sydney after losing his job in 1886. Worked as compositor on Sydney newspapers and active in the Typographical Association of New South Wales. Delegate to the NSW Trades and Labor Council 1890. -

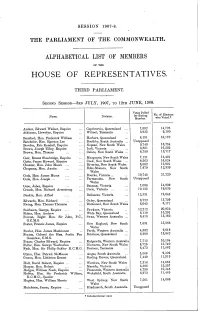

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G.