The Governor–General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Attitudes to Conscription: 1914–1918

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2016–17 27 OCTOBER 2016 Political attitudes to conscription: 1914–1918 Dr Nathan Church Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Attitudes of the Australian Labor Party ........................................................ 2 Federal government ......................................................................................... 2 New South Wales ............................................................................................. 7 Victoria ............................................................................................................. 8 Queensland ...................................................................................................... 9 Western Australia ........................................................................................... 10 South Australia ............................................................................................... 11 Political impact on the ALP ............................................................................... 11 Attitudes of the Commonwealth Liberal Party ............................................. 12 Attitudes of the Nationalist Party of Australia ............................................. 13 The second conscription plebiscite .................................................................. 14 Conclusion ................................................................................................ -

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

Ben Chifley: the True Believer1

1 Ben Chifley: the true believer John Hawkins2 Chifley was a ‘true believer’ in the Labor Party and in the role that government could play in stabilising the economy and keeping unemployment low. He was an active treasurer, initially working well with Prime Minister Curtin and then serving as both Prime Minister and Treasurer himself. He managed the war economy competently and achieved a smooth transition to a peacetime economy, although he allowed inflationary pressures to build up in the post-war years. Among his economic reforms were increased welfare payments, uniform income taxation and developing central banking powers (through direct controls rather than market mechanisms) for the Commonwealth Bank. Source: National Library of Australia.3 1 Arthur Fadden served almost a year as treasurer before Chifley, but as Chifley was Treasurer for most of the 1940s and Fadden for most of the 1950s, the essay on Chifley is being presented first in this series. 2 The author formerly worked in the Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from comments provided by Selwyn Cornish, Robin McLachlan, Sam Malloy and Richard Grant. Thanks are also extended to the staff of the Chifley Home in Bathurst. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 103 Ben Chifley: the true believer Introduction The Right Honorable Joseph Benedict Chifley was a ‘true believer’ in the Labor cause.4 While an idealist, remembered for coining the term 'light on the hill' to capture -

CHAPTER SI1 IF the Prime Minister's Assertion of The

CHAPTER SI1 THE LAST MONTHS OF THE WAR IF the Prime Minister’s assertion of the intention of his Government-to “ decline to take responsibility for the conduct of public affairs ” unless given power to secure re- inforcements by compulsion-had been less emphatic, and had contained a convenient conditional phrase, the political predicaiiient caused by the referendum of 1917 would have been avoided. But it was a peculiarly hard and fast declara- tion, without the semblance of a limitation. Similar declara- tions were made by other members of the ministry. hir. Hughes’s “ Merry Christmas,” at his country home in the Dandenong Ranges a few days after the referendum, was therefore marred by the prospect of having to carry out his pledge by placing his resignation in the hands of the Governor-General. Ministers and members of Parliament spent the traditional Season of “peace and good will,” both of which were con- spicuously deficient at this time, at their homes, but in the first week of a hot Melbourne January they began to gather at the seat of government. Parliament was to meet in the second week of that month. Speculation as to what would happen kept political circles agog. Would Mr. Hughes resign after all ? Would the Nationalist party insist upon keeping him to his undertaking? Would the whole ministry retire and give place to a fresh combination? If so, who would succeed as Prime Minister? During the opening days of thc new year there glimmered upon the horizon a streak which seemed to preqage storm. Sir John Forrest was reported--and the report was not afterwards denied--to be in disagreement with his colleagues, and there were com- mentators in the Nationalist journals who expressed doubts about Mr. -

Presentation to the Senate Modernization Committee

Presentation to the Senate Modernization Committee The Senate and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms JAMES B. KELLY Professor Department of Political Science Concordia University May 10, 2017 1 There are 4 broad reforms that should be considered to ensure a more transparent approach to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by the Minister of Justice, as well as to modernize the role of the Senate in respect to rights-based scrutiny and the legislative process. 1. Change the Minister of Justice’s reporting duty in regard to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms from simply allowing a statement of incompatibility (SOI) to also require a statement of compatibility (SOC) for all government bills modelled after the approach in the Commonwealth of Australia. For private members’ bills (PMBs), the Minister of Justice should be required to review all PMBs that progress past second reading. Because PMBs have a higher probability of being found incompatible with the Charter of Rights, as the Department of Justice does not assist in the preparation of PMBS, a revised section 4.1.1. of the Department of Justice Act should retain the ability of the Minister of Justice to issue a statement of incompatibility in this context. 2. Establish a dedicated parliamentary committee with the sole mandate to receive and review statements of compatibility, and to issue an independent assessment of Charter compatibility of all government bills, and all PMBS that progress past second reading. This committee should be a joint committee of the Parliament of Canada modelled after the Joint Committee on Human Rights (JCHR) in the United Kingdom and the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights (PJCHR) in Australia. -

John Curtin's War

backroom briefings John Curtin's war CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL backroom briefings John Curtin's WAR edited by CLEM LLOYD & RICHARD HALL from original notes compiled by Frederick T. Smith National Library of Australia Canberra 1997 Front cover: Montage of photographs of John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, 1941-45, and of Old Parliament House, Canberra Photographs from the National Library's Pictorial Collection Back cover: Caricature of John Curtin by Dubois Bulletin, 8 October 1941 Published by the National Library of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 © National Library of Australia 1997 Introduction and annotations © Clem Lloyd and Richard Hall Every reasonable endeavour has been made to contact relevant copyright holders of illustrative material. Where this has not proved possible, the copyright holders are invited to contact the publisher. National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data Backroom briefings: John Curtin's war. Includes index. ISBN 0 642 10688 6. 1. Curtin, John, 1885-1945. 2. World War, 1939-1945— Press coverage—Australia. 3. Journalism—Australia. I. Smith, FT. (Frederick T.). II. Lloyd, C.J. (Clement John), 1939- . III. Hall, Richard, 1937- . 940.5394 Editor: Julie Stokes Designer: Beverly Swifte Picture researcher/proofreader: Tony Twining Printed by Goanna Print, Canberra Published with the assistance of the Lloyd Ross Forum CONTENTS Fred Smith and the secret briefings 1 John Curtin's war 12 Acknowledgements 38 Highly confidential: press briefings, June 1942-January 1945 39 Introduction by F.T. Smith 40 Chronology of events; Briefings 42 Index 242 rederick Thomas Smith was born in Balmain, Sydney, Fon 18 December 1904, one of a family of two brothers and two sisters. -

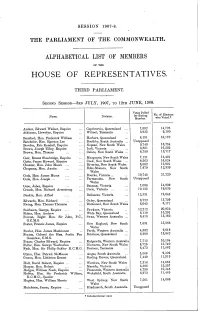

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

Prime Ministers of Australia

Prime Ministers of Australia No. Prime Minister Term of office Party 1. Edmund Barton 1.1.1901 – 24.9.1903 Protectionist Party 2. Alfred Deakin (1st time) 24.9.1903 – 27.4.1904 Protectionist Party 3. John Christian Watson 27.4.1904 – 18.8.1904 Australian Labor Party 4. George Houstoun Reid 18.8.1904 – 5.7.1905 Free Trade Party - Alfred Deakin (2nd time) 5.7.1905 – 13.11.1908 Protectionist Party 5. Andrew Fisher (1st time) 13.11.1908 – 2.6.1909 Australian Labor Party - Alfred Deakin (3rd time) 2.6.1909 – 29.4.1910 Commonwealth Liberal Party - Andrew Fisher (2nd time) 29.4.1910 – 24.6.1913 Australian Labor Party 6. Joseph Cook 24.6.1913 – 17.9.1914 Commonwealth Liberal Party - Andrew Fisher (3rd time) 17.9.1914 – 27.10.1915 Australian Labor Party 7. William Morris Hughes 27.10.1915 – 9.2.1923 Australian Labor Party (to 1916); National Labor Party (1916-17); Nationalist Party (1917-23) 8. Stanley Melbourne Bruce 9.2.1923 – 22.10.1929 Nationalist Party 9. James Henry Scullin 22.10.1929 – 6.1.1932 Australian Labor Party 10. Joseph Aloysius Lyons 6.1.1932 – 7.4.1939 United Australia Party 11. Earle Christmas Grafton Page 7.4.1939 – 26.4.1939 Country Party 12. Robert Gordon Menzies 26.4.1939 – 29.8.1941 United Australia Party (1st time) 13. Arthur William Fadden 29.8.1941 – 7.10.1941 Country Party 14. John Joseph Ambrose Curtin 7.10.1941 – 5.7.1945 Australian Labor Party 15. Francis Michael Forde 6.7.1945 – 13.7.1945 Australian Labor Party 16. -

How Federal Theory Supports States' Rights Michelle Evans

The Western Australian Jurist Vol. 1, 2010 RETHINKING THE FEDERAL BALANCE: HOW FEDERAL THEORY SUPPORTS STATES’ RIGHTS MICHELLE EVANS* Abstract Existing judicial and academic debates about the federal balance have their basis in theories of constitutional interpretation, in particular literalism and intentionalism (originalism). This paper seeks to examine the federal balance in a new light, by looking beyond these theories of constitutional interpretation to federal theory itself. An examination of federal theory highlights that in a federal system, the States must retain their powers and independence as much as possible, and must be, at the very least, on an equal footing with the central (Commonwealth) government, whose powers should be limited. Whilst this material lends support to intentionalism as a preferred method of constitutional interpretation, the focus of this paper is not on the current debate of whether literalism, intentionalism or the living constitution method of interpretation should be preferred, but seeks to place Australian federalism within the broader context of federal theory and how it should be applied to protect the Constitution as a federal document. Although federal theory is embedded in the text and structure of the Constitution itself, the High Court‟s generous interpretation of Commonwealth powers post-Engineers has led to increased centralisation to the detriment of the States. The result is that the Australian system of government has become less than a true federation. I INTRODUCTION Within Australia, federalism has been under attack. The Commonwealth has been using its financial powers and increased legislative power to intervene in areas of State responsibility. Centralism appears to be the order of the day.1 Today the Federal landscape looks very different to how it looked when the Australian Colonies originally „agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth‟2, commencing from 1 January 1901. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

Introducing John Joseph Curtin Australian Wartime Prime Minister

Introducing John Joseph Curtin, Australian war time prime minister It is my pleasure and privilege today to introduce you to the life of John Joseph Curtin-known more fully as John Joseph Ambrose Curtin but more usually as simply John Curtin.1 From my perspective there has always been a fascination in the United States with the image of a person born in a log cabin and becoming president in the White House and many years ago I remember clearly writing a biography of Abraham Lincoln with just that image to help make the story meaningful even to Australian school children. Lincoln, I seem to recall, was born in a one room log cabin in Kentucky and moved first to Indiana and then to Illinois from where his political career spiralled. Curtin was not actually born in a single room log cabin but in a small but adequate weather board home with a shingles roof in a mining town {Creswick) in Victoria. If Lincoln will always be remembered for leading his country during the American Civil War Curtin will always be remembered for leading his country when for the first and only time in its history since European settlement in 1788 there were bombing raids from the air and sea and when the threat of invasion by a hostile force was very real. In my own home (I was six years old at the time) I s till recall the air raid shelters in our backyard and the blackout on our windows and, can I add, the party staged for us by the Americans in gratitude for the hospitality we showed their sailors and airmen while they were based in Perth, (also Curtin's home town by that time).