Corowa (1893) and Bathurst (1896)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murrumbidgee Regional Fact Sheet

Murrumbidgee region Overview The Murrumbidgee region is home The river and national parks provide to about 550,000 people and covers ideal spots for swimming, fishing, 84,000 km2 – 8% of the Murray– bushwalking, camping and bird Darling Basin. watching. Dryland cropping, grazing and The Murrumbidgee River provides irrigated agriculture are important a critical water supply to several industries, with 42% of NSW grapes regional centres and towns including and 50% of Australia’s rice grown in Canberra, Gundagai, Wagga Wagga, the region. Narrandera, Leeton, Griffith, Hay and Balranald. The region’s villages Chicken production employs such as Goolgowi, Merriwagga and 350 people in the area, aquaculture Carrathool use aquifers and deep allows the production of Murray bores as their potable supply. cod and cotton has also been grown since 2010. Image: Murrumbidgee River at Wagga Wagga, NSW Carnarvon N.P. r e v i r e R iv e R v i o g N re r r e a v i W R o l g n Augathella a L r e v i R d r a W Chesterton Range N.P. Charleville Mitchell Morven Roma Cheepie Miles River Chinchilla amine Cond Condamine k e e r r ve C i R l M e a nn a h lo Dalby c r a Surat a B e n e o B a Wyandra R Tara i v e r QUEENSLAND Brisbane Toowoomba Moonie Thrushton er National e Riv ooni Park M k Beardmore Reservoir Millmerran e r e ve r i R C ir e e St George W n i Allora b e Bollon N r e Jack Taylor Weir iv R Cunnamulla e n n N lo k a e B Warwick e r C Inglewood a l a l l a g n u Coolmunda Reservoir M N acintyre River Goondiwindi 25 Dirranbandi M Stanthorpe 0 50 Currawinya N.P. -

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

Howlong News My Golf

Friday 13th March, 2020 HOWLONG NEWS MY GOLF Pictured: Some of our MyGolf participants practicing their putting skills on Sunday 1st March In case you’re wondering, the putt on the right went in! FROM PRESIDENT KIM GRAY Welcome to our March newsletter. 2020 at Clubhouse reception for absentee members who present themselves at reception. The Club’s Financial Report has been completed and externally audited, reviewed by the Board Under the triennial system three positions will and approved for the year ended 30th be vacated by rotation and any qualifying November 2019. A Profit of $52,742 has been member may nominate for a position on the reported for the year and whilst this is below Board for a three year term. I am available to our initial budget expectations we understand discuss with any prospective member any the stresses which have prevailed during the details regarding the role of a Director prior to year. An opportunity to detail our result will be the closure of nominations on Monday 16th open to members at our Information evening to April at 5:00pm. I intend re-nominating for the be held at 5pm on Monday 30th March at the President’s position. club. An important resolution has also been passed by Our Annual General Meeting is scheduled for the Board which will disallow the use of Monday 20th April 2020 and I am pleased to Members Points for the payment of advise that a change to voting process has been Membership fees with effect forthwith. We approved by the Board, which will allow pre understand this may not necessarily be popular AGM Voting. -

Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Arts Papers and Journal Articles School of Humanities and Creative Arts 6-7-2016 Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director Stephen Vagg FremantleMedia Australia, [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/arts_papers Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Vagg, S., & Reynaud, D. (2016). Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten pioneer Australian film director. Studies in Australasian Cinema, 10(2),184-198. doi:10.1080/17503175.2016.1170950 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities and Creative Arts at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Papers and Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alfred Rolfe: Forgotten Pioneer Australian Film Director Stephen Vagg Author and screenwriter, Melbourne Victoria, Australia Email: [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Faculty of Arts, Nursing & Theology, Avondale College of Higher Education, Cooranbong, NSW, Australia Email: [email protected] Daniel Reynaud Postal address: PO Box 19, Cooranbong NSW 2265 Phone: (02) 4980 2196 Bios: Stephen Vagg has a MA Honours in Screen Studies from the Australian Film, Television and Radio School and has written a full-length biography on Rod Taylor. He is also an AWGIE winning and AFI nominated screenwriter who is currently story producer on Neighbours. Daniel Reynaud is Associate Professor of History and Faculty Assistant Dean, Learning and Teaching. He has published widely on Australian war cinema and was instrumental in the partial reconstruction of Rolfe’s film The Hero of the Dardanelles, and the rediscovery of parts of How We Beat the Emden. -

Albury CLSD Minutes 26 August 2020, 1:30-3:30, Via Video Conference

Albury CLSD Minutes 26 August 2020, 1:30-3:30, via video conference Present: Winnecke Baker (Legal Aid NSW), Simon Crase (CLSD Coordinator, UMFC/HRCLS), Kerry Wright (Legal Aid NSW WDO Team), Julie Maron (Legal Aid NSW), Sue Beddowes (Interreach Albury), Jesmine Coromandel (Manager, WDVCAS), Michelle Conroy (One Door Family and Carer Mental Health Program), Susan Morris (One Door Family and Carer Mental Health Program), Diane Small (Albury City Council), Scott Boyle (Anglicare Financial Counselling), Heidi Bradbrun (Justice Conect), Nicole Stack (Legal Aid WDO Team), Julie Bye (EWON), Britt Cooksey (Amaranth Foundation Corowa), Natalie Neumann (Legal Aid NSW), Diana Elliot (Mirambeena Community Centre), Kim Andersen (Centacare South West NSW), Navinesh Nand (Legal Aid NSW), Stacey Telford (Safety Action Meeting Coordinator), Jenny Rawlings (Department of Communities and Justice – Housing), Nicole Dwyer (SIC Legal Aid NSW Riverina/Murray), Andrea Georgiou (HRCLS) Apologies: Jenny Ryder (Amaranth Foundation) Agenda Item Discussion Action/Responsibility/Time 1. Welcome, Simon acknowledged the respective Aboriginal lands that partners called in from today and welcomed purpose & everyone to the meeting. acknowledgement 2. Service check-in Susan Morris and Michelle Conroy – One Door Family and Carer Mental Health Susan: [email protected] 0488 288 707 (mon-wed) Michelle: 0481 010 728 [email protected] (tues, wed, thurs) FREE service that people can engage with as many times as they need to. Support groups are available in Albury, Corowa and Deniliquin. Both mostly working from home, but Michelle is getting back on the road. Albury CLSD Program Albury Regional Coordinator [email protected] – 0488 792 366 1 Nicole Stack and Kerry Wright – Legal Aid WDO team 4228 8299 or [email protected] Cover the NSW South Coast and Riverina/Murray. -

A Response to the Draft Guide to the Murray Darling Basin Plan

A Response to the Draft Guide to the Murray Darling Basin Plan 152 Oaklands Road Berrigan 2712 NSW ‐ 03 5885 2392 0416 156429 [email protected] 1 | Page A Brief History of West Corurgan P.I.D: The concept of the West Corurgan Private Irrigation District was first recorded in a document ‘The Case for Corugan’ published in 1938. From that point the commitment of the proponents of the scheme was unwavering right up to the commissioning of the West Corurgan Private Irrigation District on the 12th of April 1969. The District straddles the municipalities of Berrigan, Corowa, Jerilderie and Urana, covering a tract of land 212,000 hectares, delivering irrigation to 21,200 hectares via 565 kilometres of open channel. The Headworks is located 10 kilometres downstream of Corowa, lifting water 13 metres via 5 pumps into the Main Channel. From there the water is dispersed via gravity over the entire length and breadth of the district as far northwest as the Billabong Creek. The district is bounded by the townships of Berrigan, Corowa, Oaklands, Jerilderie and Urana. Agribusiness in the district includes but is not limited to beef, dairy, lamb and pork production, wool as well as rice, wheat, barley, potato and fodder cropping. Future agribusiness enterprises include but are not limited to fruit and vegetable production utilising open and reticulating irrigation practices together with wine grapes, flowers and aquaculture enterprises. The W.C.P.I.D is privately owned and fully funded by its membership. It does not enjoy the benefit of any funding or financial assistance by the State or Federal government. -

A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States

Buffalo Law Review Volume 4 Number 2 Article 2 1-1-1955 A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States Zelman Cowan Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Zelman Cowan, A Comparison of the Constitutions of Australia and the United States, 4 Buff. L. Rev. 155 (1955). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol4/iss2/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE CONSTITUTIONS OF AUSTRALIA AND THE UNITED STATES * ZELMAN COWAN** The Commonwealth of Australia celebrated its fiftieth birth- day only three years ago. It came into existence in January 1901 under the terms of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, which was a statute of the United Kingdom Parliament. Its origin in a 1 British Act of Parliament did not mean that the driving force for the establishment of the federation came from outside Australia. During the last decade of the nineteenth cen- tury, there had been considerable activity in Australia in support of the federal movement. A national convention met at Sydney in 1891 and approved a draft constitution. After a lapse of some years, another convention met in 1897-8, successively in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. -

Australian Federation: Its Aims and Its Possibilities

Australian Federation: Its Aims and its Possibilities Willoughby, Howard A digital text sponsored by New South Wales Centenary of Federation Committee University of Sydney Library Sydney 2001 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/fed/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by Sands & Mcdougall Limited, Collins Street Melbourne 1891 First Published: 1891 Languages: Latin Australian Etexts 1890-1909 prose nonfiction federation 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Australian Federation: Its Aims and its Possibilities With a Digest of the Proposed Constitution, Official Statistics, and a Review of the National Convention by Melbourne Sands & Mcdougall Limited, Collins Street 1891 Preface. THE first portion of this work appeared in the columns of the Melbourne Argus. The republication is at the request of many readers, and with the kind consent of the proprietors of the journal in question. The object in view has been to put principles before the public rather than details, because the subject itself is new to most of us; it has been talked about after public dinners, rather than thought out in the closet; and unless principles are grasped it may not be easy to arrange the compromises on which all federations are founded. In the following pages the writer has endeavoured to state certain vital principles as clearly as was in his power, and to strongly, though fairly, advocate their adoption. For instance, the necessity for a Customs union is maintained throughout. But as a rule his aim is to give both sides of a case, so that the problem may be grasped, and so that federalists who differ may do so with good feeling and with mutual respect, and without injury to the national cause on which so much depends. -

Frederick Fisher and the Legend of Fisher's Ghost Booklet(4MB, PDF)

Frederick Fisher and the legend of Fisher’s Ghost Your guide to Campbelltown’s most infamous resident Frederick Fisher and the legend of Fisher’s Ghost The legend of Fisher’s Ghost is one of Australia’s most well-known ghost stories. Since John Farley first told the story of his encounter with the spectre, tales of the ghost have inspired writers, artists, poets, songwriters and film producers, and captivated the imagination of generations. Who was Frederick Fisher? Frederick George James Fisher was born in London on 28 August 1792. He was the son of James and Ann Fisher, who were London bookbinders and booksellers of Cripplegate and Greenwich. Fred was of average height, had a fair complexion and brown hair. By his early 20s, he was a shopkeeper, and although unmarried, was believed to possibly be the father of two children. Either innocently or deliberately, Fred obtained forged bank notes through his business for which he was arrested and tried at the Surrey Gaol Delivery on 26 July 26 1815. He was sentenced to 14 years transportation to Australia with 194 other convicts aboard the Atlas, which set sail from England on 16 January 1816, and landed in Australia eight months later, on 16 September 1816. Fred Fisher could read and write and because literate men were rare in the colony, the crown solicitor recommended him to the colonial administrator, TJ Campbell, who attached Fred to his staff. Within two years, Fred was assigned as superintendent to the Waterloo Flour Company, which was owned and managed by ex-convicts and was the most influential and dynamic enterprise in colonial NSW. -

•B •M Abbonarsi a MUSICA Significa Sostenere Una Rivista Indipendente

PETRASSI dalla Chaconne,tuttocio` che e` pos- Piccolo Trio pianoforte Andrea Rucli sibile cavarne di interessante, dando clarinetto Nicola Bulfone violino Lucio abbonarsi a MUSICA Degani la dimostrazione della sua... consan- BONGIOVANNI GB 5180-2 guineita` con il Novecento musicale significa sostenere DDD 69:57 .M non di avanguardia. una rivista HHHH La stessa dimostrazione ci viene da- indipendente ta dalle due composizioni per pia- Si e` giu` parlato noforte e orchestra. Nato nel 1923, su queste pagine l’americano Peter Mennin (anzi, dell’attivissima italoamericano: si chiamava Menni- Associazione king, pianista molto eccitabile che ni), fu regolarmente eseguito negli CD Sergio Gaggia di Stati Uniti e pochissimo in Europa. suonava le musiche contemporanee Cividale del PETRASSI Concerto per flauto flauto curando poco la pulizia tecnica ma Friuli (www.sergiogaggia.com), re- Oggi la sopravvivenza del suo no- Mario Ancillotti Orchestra Sinfonica di me e` affidata alla Canzona per ban- Roma, direttore Francesco La Vec- con uno slancio travolgente. Pecca- censendo gli atti del convegno de- da, ma soprattutto al disco, che con chia to che la sua esecuzione non sia sta- dicato alla figura di Ella Adaı¨ewsky, lui fu assai generoso, tanto che pos- Concerto per pianoforte » pianoforte ta registrata. Per un motivo. Oltre nonche´ il suo « Un voyage a` Re´- siamo ascoltare tutte le sue nove Bruno Canino Orchestra Sinfonica di alle indicazioni di metronomo la sia », fondamentale testo etnomusi- Roma, direttore Francesco La Vec- partitura reca l’indicazione di dura- Sinfonie.IlConcerto per pianoforte fu chia cologico ritrovato nel 2009 e pub- commissionato a Mennin dall’Or- Suite sinfonica dal balletto « La Follia ta:«25’circa».Inquestodiscoil blicato poi da Lim. -

Australian Federation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVES' ASSOCIATION. VICTORIAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS. AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION: LECTURE ON The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia Bill, AS ADOPTED BY THE NATIONAL AUSTRALASIAN CONVENTION AT SYDNEY, 9th April, 1891. Jr. H- TvL«,.J (1*PJ F. W. Niven & Co., Printers, &c., Melbourne and Ballarat. AUSTRALIAN FEDERATION. THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. Although now brought within the range of practical politics for the first time, the Federation of Australia is no new subject. Indeed one is surprised on going through the records of Australian politics to find how old it is. It appears almost simultaneously ^vith the foundation in Australia of other colonies than New South Wales. For just as clearly as the early colonists saw that the division of our island continent into separate self-governing colonies was absolutely necessary for the proper development of the material resources of its vast territory, so clearly did they see that the re-union of these separate colonies under a federation, wherebjr they would be united under one national Government without their separate administrations, legislatures, and local patriotisms being extinguished, would be as necessary for the full development of the national life of their people. The first move in the matter was in 1849, when a committee of the British Privy Council, appointed at the instance of Earl Grey, reported on the subject. At that time there were only jthree colonies on the mainland, viz., New South Wales, South Australia, and Western Australia. The report of the committee was adopted by Earl Grey, and a bill to give effect thereto was introduced into the British Parliament in the following year, but meeting with opposition was abandoned. -

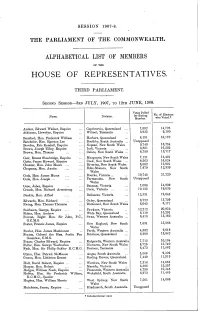

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G.