The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

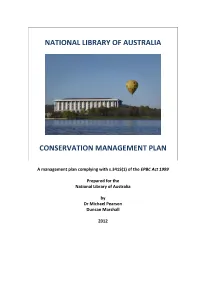

National Library of Australia Conservation Management Plan

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN A management plan complying with s.341S(1) of the EPBC Act 1999 Prepared for the National Library of Australia by Dr Michael Pearson Duncan Marshall 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Conservation Management Plan (CMP), which satisfies section 341S and 341V of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), provides the framework and basis for the conservation and good management of the National Library of Australia building, in recognition of its heritage values. The National Library of Australia’s Heritage Strategy, which details the Library’s objectives and strategic approach for the conservation of heritage values, has been prepared and accepted by the then Minister on 24 August 2006. The Heritage Strategy will be reviewed during 2012 in parallel with the endorsement of this plan. The Policies in this plan support the directions of the Heritage Strategy, and indicate the objectives for identification, protection, conservation, presentation and transmission to all generations of the Commonwealth Heritage values of the place. The CMP presents the history of the creation of the National Library of Australia and the construction of its building, describes the elements that have heritage significance, and assesses that significance using the Commonwealth Heritage List criteria. The plan outlines the obligations, opportunities and constraints affecting the management and conservation of the Library. A set of conservation policies are presented, with implementation -

Justice Richard O'connor and Federation Richard Edward O

1 By Patrick O’Sullivan Justice Richard O’Connor and Federation Richard Edward O’Connor was born 4 August 1854 in Glebe, New South Wales, to Richard O’Connor and Mary-Anne O’Connor, née Harnett (Rutledge 1988). The third son in the family (Rutledge 1988) to a highly accomplished father, Australian-born in a young country of – particularly Irish – immigrants, a country struggling to forge itself an identity, he felt driven to achieve. Contemporaries noted his personable nature and disarming geniality (Rutledge 1988) like his lifelong friend Edmund Barton and, again like Barton, O’Connor was to go on to be a key player in the Federation of the Australian colonies, particularly the drafting of the Constitution and the establishment of the High Court of Australia. Richard O’Connor Snr, his father, was a devout Roman Catholic who contributed greatly to the growth of Church and public facilities in Australia, principally in the Sydney area (Jeckeln 1974). Educated, cultured, and trained in multiple instruments (Jeckeln 1974), O’Connor placed great emphasis on learning in a young man’s life and this is reflected in the years his son spent attaining a rounded and varied education; under Catholic instruction at St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst for six years, before completing his higher education at the non- denominational Sydney Grammar School in 1867 where young Richard O’Connor met and befriended Edmund Barton (Rutledge 1988). He went on to study at the University of Sydney, attaining a Bachelor of Arts in 1871 and Master of Arts in 1873, residing at St John’s College (of which his father was a founding fellow) during this period. -

JHSSA Index 2014

Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Subject Index 1975-2014 Nos 1 to 42 Compiled by Brian Samuels The Historical Society of South Australia Inc PO Box 519 Kent Town 5071 South Australia JHSSA Subject Index 1975–2014 page 35 Subject Index 1975-2014: Nos 1 to 42 This index consolidates and updates the Subject Index to the Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia Nos 1 - 20 (1974 [sic] - 1992) which appeared in the 1993 Journal and its successors for Nos 21 - 25 (1998 Journal) and 26 - 30 (2003 Journal). In the latter index new headings for Gardens, Forestry, Place Names and Utilities were added and some associated reindexing of the entire index database was therefore undertaken. The indexing of a few other entries was also improved, as has occurred with this latest updating, in which Heritage Conservation and Imperial Relations are new headings while Death Rituals has been subsumed into Folklife. The index has certain limitations of design. It uses a limited number of, and in many instances relatively broad, subject headings. It indexes only the main subjects of each article, judged primarily from the title, and does not index the contents – although Biography and Places have subheadings. Authors and titles are not separately indexed, but they do comprise separate fields in the index database. Hence author and title indexes could be included in future published indexes if required. Titles are cited as they appear at the head of each article. Occasionally a note in square brackets has been added to clarify or amplify a title. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

Women in the Federal Parliament

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 17 September 1992 Trust the Women Women in the Federal Parliament Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Senate Department. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Senate Department Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3061 The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. First published 1992 Reprinted 1993 Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Note This issue of Papers on Parliament brings together a collection of papers given during the first half of 1992 as part of the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series and in conjunction with an exhibition on the history of women in the federal Parliament, entitled, Trust the Women. Also included in this issue is the address given by Senator Patricia Giles at the opening of the Trust the Women exhibition which took place on 27 February 1992. The exhibition was held in the public area at Parliament House, Canberra and will remain in place until the end of June 1993. Senator Patricia Giles has represented the Australian Labor Party for Western Australia since 1980 having served on numerous Senate committees as well as having been an inaugural member of the World Women Parliamentarians for Peace and, at one time, its President. Dr Marian Sawer is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Canberra, and has written widely on women in Australian society, including, with Marian Simms, A Woman's Place: Women and Politics in Australia. -

Yet We Are Told That Australians Do Not Sympathise with Ireland’

UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE ‘Yet we are told that Australians do not sympathise with Ireland’ A study of South Australian support for Irish Home Rule, 1883 to 1912 Fidelma E. M. Breen This thesis was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Research in the Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Adelaide. September 2013. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .............................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 4 Declaration ........................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. 6 ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 7 CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................ 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 WHAT WAS THE HOME RULE MOVEMENT? ................................................................. 17 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE .................................................................................... -

Process, but Also Assumes a Role in the Administration of the Court

Mason process, but also assumes a role in the administration of the Court. Frank Jones Mason, Anthony Frank (b 21 April 1925; Justice 1972–87; Chief Justice 1987–95) was a member of the High Court for 23 years and is regarded by many as one of Australia’s great- est judges, as important and influential as Dixon.The ninth Chief Justice,he presided over a period ofsignificant change in the Australian legal system, his eight years as Chief Justice having been described as among the most exciting and important in the Court’s history. Mason grew up in Sydney, where he attended Sydney Grammar School. His father was a surveyor who urged him to follow in his footsteps; however, Mason preferred to follow in the footsteps of his uncle, a prominent Sydney KC. After serving with the RAAF as a flying officer from 1944 to 1945, he enrolled at the University of Sydney, graduating with first-class honours in both law and arts. Mason was then articled with Clayton Utz & Co in Sydney, where he met his wife Patricia, with whom he has two sons. He also served as an associate to Justice David Roper of the Supreme Court of NSW. He moved to the Sydney Bar in 1951, where he was an unqualified success, becoming one of Barwick’s favourite junior counsel. Mason’s practice was primarily in equity and commercial law,but he also took on a number ofconstitutional and appellate cases. After only three years at the Bar, he appeared before the High Court in R v Davison (1954), in which he successfully persuaded the Bench that certain sections of the Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth) invalidly purported to confer Anthony Mason, Justice 1972–87, Chief Justice 1987–95 in judicial power upon a registrar of the Bankruptcy Court. -

Scènes De La Vie Australienne

PAULMAISTRE SCENES DE LA VIE AUSTRALIENNE "De mineur a ministre" Translated and introduced by C. B. Thornton-Smith Introduction "De mineur a ministre" appeared in the latter half of 1896 as the fourth in a series of five short stories set in Australia which Paul Maistre published in the Madrid-based Nouvelle Revue Internationale between 1894 and 1897. The fact that he was a vice- consul of France in Melbourne during this time made it essential that he use a pen- name, with his choice of "Paul le Franc" being particularly apt given his frank comments on the delusions and vagaries of the Anglo-Saxons, including according to him the Scots, against whom he seems to have had a particular animus. All five stories are written from a clearly French perspective, with some of them having a "beau role" for a French character. In this one, reacting to the assumed racial and moral superiority of Anglo-Saxons, he offers caustic comments on such matters as Sabbatarianism, temperance movements, long-winded and empty oratory, lack of commercial morality and obsession with symbols of status. As a consular official doing his best to assist French commercial interests in Victoria, he was particularly exercised by that colony's protectionist policies which artificially inflated the cost of French imports. Just over a century later, the climax of his story has considerable topicality given that, while not quite illustrating the "Plus ca change ..." principle, the excesses of "high-fliers" and financial crash of the 1980s have remarkable similarities in almost everything but scale to those of the 1890s, which brought about the demise of "Marvellous Melbourne". -

Stephen Wilks Review of John Murphy, Evatt: a Life

Stephen Wilks review of John Murphy, Evatt: A Life (Sydney, NSW: NewSouth Publishing, 2016), 464 pp., HB $49.99, ISBN 9781742234465 When Herbert Vere Evatt died in November 1965 he was buried at Woden cemetery in Canberra’s south. His grave proclaims him as ‘President of the United Nations’ and reinforces the point by bearing the United Nations (UN) emblem. Misleading as this is—as president of the UN General Assembly rather than secretary-general, Evatt was more presiding officer than chief executive—it broadcasts his proud internationalism. The headstone inscription is equally bold—‘Son of Australia’. The Evatt memorial in St John’s Anglican Church in inner Canberra is more subtle. This depicts a pelican drawing its own blood to feed its young, a classical symbol of self-sacrifice and devotion. These idealistic, almost sentimental, commemorations clash with the dominant image of Evatt as a political wrecker. This casts him as the woefully narcissistic leader of the federal parliamentary Labor Party who provoked the great split of 1954, when the party’s predominantly Catholic anti-communist right exited to form the Democratic Labor Party and help keep Labor out of office for the next 18 years. This spectre looms over Evatt’s independent Australian foreign policy and championing of civil liberties during the Cold War. John Murphy’s Evatt: A Life is the fourth full biography of the man, not to mention several more focused studies. This is better than most Australian prime ministers have managed. Evatt invites investigation as a coruscating intelligence with a clarion world view. His foremost achievements were in foreign affairs, a field attractive to Australian historians. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

CHAPTER SI1 IF the Prime Minister's Assertion of The

CHAPTER SI1 THE LAST MONTHS OF THE WAR IF the Prime Minister’s assertion of the intention of his Government-to “ decline to take responsibility for the conduct of public affairs ” unless given power to secure re- inforcements by compulsion-had been less emphatic, and had contained a convenient conditional phrase, the political predicaiiient caused by the referendum of 1917 would have been avoided. But it was a peculiarly hard and fast declara- tion, without the semblance of a limitation. Similar declara- tions were made by other members of the ministry. hir. Hughes’s “ Merry Christmas,” at his country home in the Dandenong Ranges a few days after the referendum, was therefore marred by the prospect of having to carry out his pledge by placing his resignation in the hands of the Governor-General. Ministers and members of Parliament spent the traditional Season of “peace and good will,” both of which were con- spicuously deficient at this time, at their homes, but in the first week of a hot Melbourne January they began to gather at the seat of government. Parliament was to meet in the second week of that month. Speculation as to what would happen kept political circles agog. Would Mr. Hughes resign after all ? Would the Nationalist party insist upon keeping him to his undertaking? Would the whole ministry retire and give place to a fresh combination? If so, who would succeed as Prime Minister? During the opening days of thc new year there glimmered upon the horizon a streak which seemed to preqage storm. Sir John Forrest was reported--and the report was not afterwards denied--to be in disagreement with his colleagues, and there were com- mentators in the Nationalist journals who expressed doubts about Mr. -

What Is Past, Or Passing, Or to Come ___ 10F What Is Past, Or Passing, Or to Come ______

1030 What is Past, or Passing, or to Come ____ 10f What is Past, or Passing, or to Come ______ ~ .... tcllbyby the HOI!HOIl Justice Michael Kirby A.C .. C.M.G., President afthealthe CaUTIo!Caurlo! Appeal afat the 1993 BenchBelich & Bar ',lrlUlerat which he was the guest afhonour.o/honour. ¥. ,!i}fi "Once 0111011I of nature I shall never raketake ~ Mybodi1yjormfrom~f bodilyfarm/rom anyany. natural (hing,rh~lIg. Asprey kept, hanging on the wall of his chambers. behind the B ~f slIcllslIch ajormalarm as Grecian goldsmithsgoldsnllfhs make chair at his desk. the famous cartoon of FE Smith. Next to that dfhammered gold and gold enamelling cartoon was hanging a mirror. Looking in the mirror"it was To keep a drowsy Emperor awake; natural to see oneself as a reflection of the great English Or set upon a golden bOllghbough to sing counsel. "[ To lords and ladies of ByzantiumByz.antium The President of the Incorporated Law Institute (as it O/wlw{OfwiwI is past.past, or passing. or to come." was called) was NormanNonnan Cowper, later to be knighted. Reg WBW B Yeats Downing was the State Auomey~General. The most senior silks were HVH V Evatt himself, his brother CliveCJive and CAC A : ....UTI< PAST Hardwick. Amongst the senior juniors were those memorable figures Wilf Sheppard, Walter Gee, Bertie Wright and On an occasion such as this, and in this common room.room, Humphrey Henchman - the lastofwhom 1I saw, evergreen, in 'ldsinevitableitisineviw,blethatthat an affliction of nostalgia will take the mind this place but a month ago. back through lheme lost years.