Referendum - the Australian Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture 2003

THE HIGH COURT’S ABANDONMENT OF ‘THE TIME-HONOURED METHODOLOGY OF THE COMMON LAW’ IN ITS INTERPRETATION OF NATIVE TITLE IN MIRRIUWUNG GAJERRONG AND YORTA YORTA Sir Ninian Stephen Annual Lecture 2003 Noel Pearson Law School University of Newcastle 17 March 2003 There are fundamental problems with the way in which the High Court has interpreted native title in Australian law in its two most recent decisions: Mirriuwung Gajerrong1 and Yorta Yorta2. In the space of this lecture I will only be able to deal with three key problems: the court‟s misinterpretation of the definition of native title in section 223(1) of the Native Title Act 1993-1998 (Cth) (“Native Title Act”) the court‟s misinterpretation of how the common law treats traditional indigenous occupants of land when the Crown acquires sovereignty over their land as an injusticiable act of State the court‟s disavowal of native title as a doctrine or body of law within the common law – 1 State of Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28 (8 August 2002). Referred to variously as Ward and Mirriuwung Gajerrong 2 Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58 (12 December 2002) 1 and its failure to judge the Yorta Yorta people‟s claim in accordance with this body of law I will close with some views about what I think needs to be done in all justice to indigenous Australians. But before I undertake this critique, let me first set out my understanding of what Mabo3 and native title should have meant to Australians. -

Curriculum Vitae Neil Young Qc

CURRICULUM VITAE NEIL YOUNG QC Address Melbourne Ninian Stephen Chambers (Chambers) Level 38, 140 William Street, Melbourne Vic 3000 Email [email protected] Clerk Michael Green – Ph 03 9225 7864 Sydney New Chambers 126 Phillip Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Email [email protected] Clerk Ian Belshaw – Ph 02 9151 2080 Present position Queen’s Counsel, all Australian States Academic LL.B (1st class honours), University of Melbourne Qualifications LL.M Harvard, 1977 Current Member of the Court of Arbitration for Sport, Geneva, since 1999 professional Director, Victorian Bar Foundation positions Director of the Melbourne Law School Foundation Board Previous Vice-Chairman, Victorian Bar Council, September 1995 to March 1997 professional Director, Barristers’ Chambers Limited, 1994 to 1998 positions Chairman of the Victorian Bar Council, March 1997 to September 1998 President, Australian Bar Association, January 1999 to February 2000 Member, Faculty of Law, University of Melbourne, 1997 2005 Member of the Monash University Faculty of Law Selection Committee, 1998 Member of the JD Advisory Board, Melbourne University, since 1999 Member of the Steering Committee, Forum of Barristers and Advocates of the International Bar Association, January 1999 to February 2000 Member of the Trade Practices and Taxation Law Committees of the Law Council of Australia Chairman of the Continuing Legal Education Committee of the Victorian Bar, 2003 – November 2005 Justice of the Federal Court of Australia, 2005-2007 Page 1 of 2 Admission Details Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Victoria since 3 March 1975 Practitioner of the High Court of Australia and the Federal Court since 3 April 1975 Signed the Victorian Bar Roll on 15 March 1979 Admitted as a barrister, or barrister and solicitor in each of the other States of Australia Appointment Appointed one of Her Majesty’s Counsel for the State of Victoria on 27 November to the Inner Bar 1990. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903. -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

Dialogue Vol. 22, 2/2003

he Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia was established in 1971. T Previously, some of the functions were carried out through the Social Science Research Council of Australia, established in 1942. Elected to the Academy for distinguished contributions to the social sciences, the 382 Fellows of the Academy offer expertise in the fields of accounting, anthropology, demography, economics, economic history, education, geography, history, law, linguistics, philosophy, political science, psychology, social medicine, sociology and statistics. The Academy’s objectives are: · to promote excellence in and encourage the advancement of the social sciences in Australia; · to act as a coordinating group for the promotion of research and teaching in the social sciences; · to foster excellence in research and to subsidise the publication of studies in the social sciences; · to encourage and assist in the formation of other national associations or institutions for the promotion of the social sciences or any branch of them; · to promote international scholarly cooperation and to act as an Australian national member of international organisations concerned with the social sciences; · to act as consultant and adviser in regard to the social sciences; and, · to comment where appropriate on national needs and priorities in the area of the social sciences. These objectives are fulfilled through a program of activities, research projects, independent advice to government and the community, publication and cooperation with fellow institutions both within -

Religious Freedom and the Australian Constitution – Origins and Future

The Denning Law Journal 2018 Vol 30 pp 207-217 RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND THE AUSTRALIAN CONSTITUTION – ORIGINS AND FUTURE Luke Beck (Routledge 2018) pp 178 Jocelynne A. Scutt* The most recent Australian Census, conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 2016 (with a 95.1 per cent response rate), confirms that Australia is ‘increasingly a story of religious diversity, with Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, and Buddhism all increasingly common religious beliefs’.1 Of these, between 2006 and 2016 Hinduism shows the ‘most significant growth’, attribut- ed to immigration from South East Asia, whilst Islam (2.6 per cent of the popu- lation) and Buddhism (2.4 per cent) were the most common religions reported next to Christianity, the latter ‘remaining the most common religion’ (52 per cent stating this as their belief). Nevertheless, Christianity is declining, drop- ping from 88 per cent in 1966 to 74 per cent in 1991, and thence to the 2016 figure. At the same time, nearly one-third of Australians (30 per cent) state they have no religion,2 this group reflecting ‘a trend for decades’ which, says the ABS, is ‘accelerating’: Those reporting no religion increased noticeably from 19% in 2006 to 30% in 2016 [with] the largest change … between 2011 (22%) and 2016, when an additional 2.2 million people reported having no religion.3 In this, there were not insignificant differences between the states: Tasmania reported the lowest religious affiliation rate (53 per cent), whilst New South Wales had the highest rate (66 per cent). Age was a significant factor, both in terms of particular religious affiliation and in the ‘no religion’ category. -

The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Harry Hobbs and Andrew Trotter* THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE: MAKING SENSE OF MULTIPLE INTENTIONS ABSTRACT The delegates to the 1890s Constitutional Conventions were well aware that the amendment mechanism is the ‘most important part of a Cons titution’, for on it ‘depends the question as to whether the state shall develop with peaceful continuity or shall suffer alternations of stagnation, retrogression, and revolution’.1 However, with only 8 of 44 proposed amendments passed in the 116 years since Federation, many commen tators have questioned whether the compromises struck by the delegates are working as intended, and others have offered proposals to amend the amending provision. This paper adds to this literature by examining in detail the evolution of s 128 of the Constitution — both during the drafting and beyond. This analysis illustrates that s 128 is caught between three competing ideologies: representative and respons ible government, popular democracy, and federalism. Understanding these multiple intentions and the delicate compromises struck by the delegates reveals the origins of s 128, facilitates a broader understanding of colonial politics and federation history, and is relevant to understanding the history of referenda as well as considerations for the section’s reform. I INTRODUCTION ver the last several years, three major issues confronting Australia’s public law framework and a fourth significant issue concerning Australia’s commitment Oto liberalism and equality have been debated, but at an institutional level progress in all four has been blocked. The constitutionality of federal grants to local government remains unresolved, momentum for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution ebbs and flows, and the prospects for marriage equality and an * Harry Hobbs is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law, Lionel Murphy postgraduate scholar, and recipient of the Sir Anthony Mason PhD Award in Public Law. -

Annual Report 2014-2015 HAEMOPHILIA FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA

annual report 2014-2015 HAEMOPHILIA FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA Haemophilia Foundation Australia (HFA) is the national peak body which represents people with haemophilia, von Willebrand disorder and other rare inherited bleeding disorders and their families throughout Australia. HFA supports a network of state and territory Foundations in Australia and as a National Member Organisation of the World Federation of Hemophilia, HFA participates in international efforts to improve access to care and treatment for people with bleeding disorders around the world. Our Mission: to inspire excellence in treatment, care and support through representation, education and promotion of research. Our Vision: for people with bleeding disorders to lead active, independent and fulfilling lives. Our Goals: good governance effective advocacy strategic education and communication financial sustainability to advance research, care and treatment to be the trusted national organisation and recognised community expert on inherited bleeding disorders Our Governance HFA is incorporated in Victoria. Its members are each of the state/territory Haemophilia Foundations around Australia. Each Foundation is represented on the HFA Council and Council elects office-bearers from its own number. At the Annual General Meeting on 25 October 2014, a special resolution to change the HFA Constitution was considered. This had been preceded by a full consultation with members and legal advice. The HFA Council subsequently adopted a number of Constitution changes aimed at creating a smaller, more efficient and agile Council. The effect of the changes was that there would no longer be an Executive Board and each member Haemophilia Foundation would have just one representative on Council. Executive Board meetings would be replaced with up to 3 Council meetings during the year. -

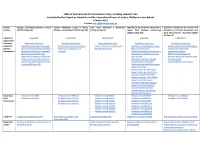

Australia and Contentious Cases

Table of Australia and ICJ Contentious Cases, including relevant links Compiled by the Project on Australia and the International Court of Justice, Melbourne Law School February 2019 Contact: [email protected] Official Nuclear Tests (New Zealand v. France) Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru East Timor (Portugal v Australia) Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v. Questions relating to the Seizure and Citation [1974] ICJ Rep 457 (Nauru v. Australia) [1992] ICJ Rep 240 [1995] ICJ Rep 90 Japan: New Zealand Intervening) Detention of Certain Documents and [2014] ICJ Rep 226 Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia) [2015] ICJ Rep 147 Australia’s Applicant Respondent Respondent Applicant Respondent Appearance Overview Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Overview of the Case Australia’s - Application Instituting Proceedings - Counter-Memorial of Australia - Counter-Memorial of Australia - Application instituting proceedings - Written observations of Australia on Written - Request for the indication of Interim - Preliminary Objections of - Rejoinder of Australia - Memorial of Australia Timor-Leste's Request for Submissions Measures of Protection of Australia Australia - Written observations of Australia on provisional measures - Memorial on Jurisdiction and the Declaration of Intervention by - Written Undertaking by the Admissibility submitted of Australia New Zealand Attorney-General of Australia dated - Written answer of Australia to the - Statement of Mr Marc Mangel 21 January 2014 question posed by Judge Gros at the (expert called by Australia) - Counter-Memorial of Australia hearing of 25 May 1973 - Statement of Mr Nick Gales (expert called by Australia) - Statement of Mr. Nick Gales (expert called by Australia) in response to the statement submitted by Mr. -

![Selected Articles and Speeches by Sir Anthony Mason AC, KBE, Geoffrey Lindell (Ed), [Sydney, Federation Press 2007 Hardback, 44 8Pp, AU$80] ISBN 9781862876521](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4632/selected-articles-and-speeches-by-sir-anthony-mason-ac-kbe-geoffrey-lindell-ed-sydney-federation-press-2007-hardback-44-8pp-au-80-isbn-9781862876521-1974632.webp)

Selected Articles and Speeches by Sir Anthony Mason AC, KBE, Geoffrey Lindell (Ed), [Sydney, Federation Press 2007 Hardback, 44 8Pp, AU$80] ISBN 9781862876521

Mason Papers: Selected Articles and Speeches by Sir Anthony Mason AC, KBE, Geoffrey Lindell (ed), [Sydney, Federation Press 2007 Hardback, 44 8pp, AU$80] ISBN 9781862876521 Judicial biographies and memoirs are scarce in Australia Unlike in the United States, scholars have only occasionally devoted entire books to the life of an Australian judge. The judges themselves have been even less forthcoming.' Some would not lament such a dearth.' However, in an age where judges seem to admit the role of personal values in their decision- making,5 biographies and memoirs should enhance lawyers' understanding of their field.6 Where a great judge, such as Sir Anthony Mason, has not yet caught the attention of a biographer, or performed a similar task himself, the law- yer still has one important source of insight beyond reported cases: extra- judicial writings. There may be limits on how far it is appropriate for judges to make such pronouncements off the Bench.' Nonetheless, it has long been a practice of the Australian judiciary and can provide useful glimpses of thinking and character that would otherwise remain hidden. The downside for the curious is that extra-judicial writings will usually be scattered across a range of publications. Even in the digital era, it can be laborious to locate and digest all pieces by a particular judge.' The problem deepens the more prolific he or she has been. Fortunately, in a handful of cases, Australian publishers have released books that collect the most sig- nificant extra-judicial writings of a judge in a single volume. 1 M. -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J.