Chapter One the Seven Pillars of Centralism: Federalism and the Engineers’ Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Negative Implications in the Interpretation of Commonwealth Legislative Powers

THE ROLE OF NEGATIVE IMPLICATIONS IN THE INTERPRETATION OF COMMONWEALTH LEGISLATIVE POWERS MICHAEL STOKES* One of the bases for the view that Commonwealth powers should be interpreted broadly is the idea that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power. The paper argues that far from being wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power it is necessary to do so in that it is impossible to interpret such grants sensibly without drawing negative implications from them. This paper considers Isaacs J’s argument in Huddart Parker that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power, as it is the most detailed defence of that position, and the adoption of similar arguments in Work Choices. It then considers the merits of Isaacs J’s argument, rejecting it because it is impossible to interpret positive grants of power without drawing negative implications from them in any context and in the Australian constitutional context in particular. This paper looks at how the scope of such implications is to be determined and how constitutional grants of power ought to be interpreted in the light of negative implications. It concludes that it is possible to determine the scope of the negative implications implicit in the s 51 grants of power and to interpret those powers in the light of the implications while accepting that state powers are residual and that their content cannot be determined until the content of all Commonwealth powers is known. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 176 II The Origin of the Argument That It Is Wrong to Draw Negative Implications from Positive Grants of Power ....................................................... -

Resolving Individual Labour Disputes: a Comparative Overview

Resolving Individual Labour Disputes A comparative overview Edited by Minawa Ebisui Sean Cooney Colin Fenwick Resolving individual labour disputes Resolving individual labour disputes: A comparative overview Edited by Minawa Ebisui, Sean Cooney and Colin Fenwick International Labour Office, Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2016 First published 2016 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Ebisui, Minawa; Cooney, Sean; Fenwick, Colin F. Resolving individual labour disputes: a comparative overview / edited by Minawa Ebisui, Sean Cooney, Colin Fenwick ; International Labour Office. - Geneva: ILO, 2016. ISBN 978-92-2-130419-7 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-130420-3 (web pdf ) International Labour Office. labour dispute / labour dispute settlement / labour relations 13.06.6 ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

LAWS2150 – Federal Constitutional Law Table of Contents

LAWS2150 – Federal Constitutional Law Table of Contents The Constitution ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Purposes of a Constitution ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Written and unwritten Constitutions .................................................................................................................... 3 Drafting the Constitution ........................................................................................................................................... 3 The High Court and Constitutional Interpretation ................................................................................ 3 Pre-Engineers Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Implied Immunity of Instrumentalities ................................................................................................................................ 3 Reserved State Powers ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 The Engineers Case ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 The Jumbunna Principle -

Right to Freedom of Association in the Workplace: Australia's Compliance with International Human Rights Law

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title The Right to Freedom of Association in the Workplace: Australia's Compliance with International Human Rights Law Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/98v0c0jj Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 27(2) Author Hutchinson, Zoé Publication Date 2010 DOI 10.5070/P8272022218 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLES THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION IN THE WORKPLACE: AUSTRALIA'S COMPLIANCE WITH INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW Zoe Hutchinson BA LLB (Hons, 1st Class)* ABSTRACT The right to freedom of association in the workplace is a well- established norm of internationalhuman rights law. However, it has traditionally received insubstantial attention within human rights scholarship. This article situates the right to freedom of as- sociation at work within human rights discourses. It looks at the status, scope and importance of the right as it has evolved in inter- nationalhuman rights law. In so doing, a case is put that there are strong reasons for states to comply with the right to freedom of association not only in terms of internationalhuman rights obliga- tions but also from the perspective of human dignity in the context of an interconnected world. A detailed case study is offered that examines the right to free- dom of association in the Australian context. There has been a series of significant changes to Australian labor law in recent years. The Rudd-Gillard Labor government claimed that recent changes were to bring Australia into greater compliance with its obligations under internationallaw. This policy was presented to electors as in sharp contrast to the Work Choices legislation of the Howard Liberal-Nationalparty coalitiongovernment. -

Constitutional Law Note

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW NOTE Topic 1, 2 – The Structure of Parliament and Legislative Procedures o The Structure .......................................................................................................... 3 o Duration and Membership ..................................................................................... 5 o Standard Legislative Procedures: Commonwealth and States ............................... 8 o Commonwealth Alternative Procedures (section 57) ............................................ 10 o Commonwealth Restrictive Procedures (section 128) .......................................... 13 o Special Procedures for Financial Legislation (section 53, 54, 55) ........................ 15 o State Restrictive Procedures .................................................................................. 19 Topic 3 – Characterisation and Interpretation o Principles of Constitutional Interpretation ............................................................. 25 o The Process of Characterisation ............................................................................. 28 Topic 4 – Financial and Economic Powers o Taxation Power – section 51(ii) ............................................................................. 33 o Grants Power – section 96 ..................................................................................... 36 o Appropriation Power – section 81 ......................................................................... 38 o Corporations Power – section 51(xx) ................................................................... -

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: a Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon*

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: A Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon* The essential and distinctive feature of “a truly federal government” is the preservation of the separate existence and corporate life of each of the component States concurrently with that of the national government. Accepting that a number of polities are contemplated as coexisting within a federation does not, however, address the fundamental question of how legislative and executive powers are to be allocated among the constituent constitutional units inter se, nor the extent to which the various polities are immune from interference occasioned by their constitutional counterparts. These “federal” questions are fundamental as they ultimately define the prism through which one views the Constitution. Shifts in the lens have resulted in significant ramifications for intergovernmental relations. This article traces the development of the Melbourne Corporation doctrine in Australia, and undertakes a comparative analysis with the development of the cognate jurisprudence in the United States. Analysis is undertaken of the major Australian industrial relations decisions, such as the Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria, Queensland Electricity Commission v Commonwealth, and United Firefighters Union of Australia v Country Fire Authority, in this context. But one of the first and most leading principles on which the commonwealth and the laws are consecrated, is left the temporary possessors -

Understanding Australian Labour Law

Ul/d"I',"I"'''/iIlK Austruliun Labour '''</\1' '27 Understanding Australian Labour Law Kerl Spooner University of Technology, Sydney TIll' purpose of II';.~paper is 10 provide an (}\'erl'iew ofthe legaljramework with in which employmetu ronditions are established in Australia. Comparative studies in lirefield of employment relations can promote understanding ofthe factors and processes that determine such phenomena and ('(III genera te a better understanding I!f our own country's institutions and practices. 71,1' need/ill" such understanding is becoming more urgent in the context (!{ globalisatio« lind the quest for some understanding of what might be deemed as socially responsible employment conditions. However, comparative international employment relation '.I' StII{~Valso presents particular chollenges, as there are international differences ill terminology as 11'1'/1 as problems in distinguishing between the loll' and actual practice. This paper aims lit assisting the development ofcomparative empkrytnen! relations studv by providing 0 detailed but simplified examination o] Australian labourIaw which mightform the basesforfuture comparative studv. Introduction Governments of all political persuasions in all industrial and industriajising countries pass laws establishing the framework within which employment relations institutions and processes are determined. The rights of individuals in employment flow either directly from legal standards established by government 01' from thlf operations of institutions and processes provided under the law. The forces of globalisation have a siglfificanl impact upon employment conditions and have increased the need for understanding of labour law at internauonal and naiional levels. There is considerable and growing pressure for multi- national organisations operating in countries offering cheap labour to provide employment conditions that are socially responsible. -

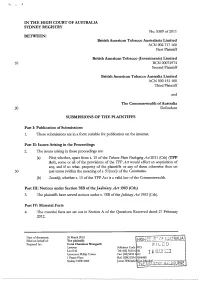

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A. -

Journal of Supreme Court History

Journal of Supreme Court History THE SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY THURGOOD MARSHALL Associate Justice (1967-1991) Journal of Supreme Court History PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Chairman Donald B. Ayer Louis R. Cohen Charles Cooper Kenneth S. Geller James J. Kilpatrick Melvin I. Urofsky BOARD OF EDITORS Melvin I. Urofsky, Chairman Herman Belz Craig Joyce David O'Brien David J. Bodenhamer Laura Kalman Michael Parrish Kermit Hall Maeva Marcus Philippa Strum MANAGING EDITOR Clare Cushman CONSULTING EDITORS Kathleen Shurtleff Patricia R. Evans James J. Kilpatrick Jennifer M. Lowe David T. Pride Supreme Court Historical Society Board of Trustees Honorary Chairman William H. Rehnquist Honorary Trustees Harry A. Blackmun Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Byron R. White Chairman President DwightD.Opperman Leon Silverman Vice Presidents VincentC. Burke,Jr. Frank C. Jones E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Secretary Treasurer Virginia Warren Daly Sheldon S. Cohen Trustees George Adams Frank B. Gilbert Stephen W. Nealon HennanBelz Dorothy Tapper Goldman Gordon O. Pehrson Barbara A. Black John D. Gordan III Leon Polsky Hugo L. Black, J r. William T. Gossett Charles B. Renfrew Vera Brown Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr. William Bradford Reynolds Wade Burger Judith Richards Hope John R. Risher, Jr. Patricia Dwinnell Butler William E. Jackson Harvey Rishikof Andrew M. Coats Rob M. Jones William P. Rogers William T. Coleman,1r. James 1. Kilpatrick Jonathan C. Rose F. Elwood Davis Peter A. Knowles Jerold S. Solovy George Didden IIJ Harvey C. Koch Kenneth Starr Charlton Dietz Jerome B. Libin Cathleen Douglas Stone John T. Dolan Maureen F. Mahoney Agnes N. Williams James Duff Howard T. -

Palmer-WA Pltf.Pdf

H I G H C O U R T O F A U S T R A L I A NOTICE OF FILING This document was filed electronically in the High Court of Australia on 23 Apr 2021 and has been accepted for filing under the High Court Rules 2004. Details of filing and important additional information are provided below. Details of Filing File Number: B52/2020 File Title: Palmer v. The State of Western Australia Registry: Brisbane Document filed: Form 27A - Appellant's submissions-Plaintiff's submissions - Revised annexure Filing party: Plaintiff Date filed: 23 Apr 2021 Important Information This Notice has been inserted as the cover page of the document which has been accepted for filing electronically. It is now taken to be part of that document for the purposes of the proceeding in the Court and contains important information for all parties to that proceeding. It must be included in the document served on each of those parties and whenever the document is reproduced for use by the Court. Plaintiff B52/2020 Page 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No B52 of 2020 BRISBANE REGISTRY BETWEEN: CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Plaintiff and STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 10 Defendant PLAINTIFF’S OUTLINE OF SUBMISSIONS Clive Frederick Palmer Date of this document: 23 April 2021 Level 17, 240 Queen Street T: 07 3832 2044 Brisbane Qld 4000 E: [email protected] Plaintiff Page 2 B52/2020 -1- PART I: FORM OF SUBMISSIONS 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART II: ISSUES PRESENTED 2. -

The Idea of a Federal Commonwealth

Chapter One Th e Idea of a Federal Commonwealth* Dr Nicholas Aroney Arguably the single most important provision in the entire body of Australian constitutional law is s. 3 of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK). Th is section authorised Queen Victoria to declare by proclamation that the people of the several Australian colonies should be united in a Federal Commonwealth under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia. Several things are at once noticeable about this provision. Of primary importance for present purposes is that, while the formation of the Commonwealth depended upon an enactment by the Imperial Parliament at Westminster and a proclamation by the Queen, the Australian Commonwealth was itself premised upon the agreement of the people of the several colonies of Australia to be united into a federal commonwealth. Th e framers of the Constitution could arguably have used any one of a number of terms to describe the nature of the political entity that they wished to see established. Th e federation was established subject to the Crown and under a Constitution, so they might have called it the Dominion of Australia and describeddescribed it as a constitutional monarchy. Th e Constitution was arguably the most democratic and liberal that the world had yet seen, so perhaps they could have called it the United States of Australia and describeddescribed it as a liberal democracy. But to conjecture in this way is to hazard anachronism. Th e framers of the Constitution chose to name it the Commonwealth of Australia and toto describedescribe it as a federal commonwealth. -

How Federal Theory Supports States' Rights Michelle Evans

The Western Australian Jurist Vol. 1, 2010 RETHINKING THE FEDERAL BALANCE: HOW FEDERAL THEORY SUPPORTS STATES’ RIGHTS MICHELLE EVANS* Abstract Existing judicial and academic debates about the federal balance have their basis in theories of constitutional interpretation, in particular literalism and intentionalism (originalism). This paper seeks to examine the federal balance in a new light, by looking beyond these theories of constitutional interpretation to federal theory itself. An examination of federal theory highlights that in a federal system, the States must retain their powers and independence as much as possible, and must be, at the very least, on an equal footing with the central (Commonwealth) government, whose powers should be limited. Whilst this material lends support to intentionalism as a preferred method of constitutional interpretation, the focus of this paper is not on the current debate of whether literalism, intentionalism or the living constitution method of interpretation should be preferred, but seeks to place Australian federalism within the broader context of federal theory and how it should be applied to protect the Constitution as a federal document. Although federal theory is embedded in the text and structure of the Constitution itself, the High Court‟s generous interpretation of Commonwealth powers post-Engineers has led to increased centralisation to the detriment of the States. The result is that the Australian system of government has become less than a true federation. I INTRODUCTION Within Australia, federalism has been under attack. The Commonwealth has been using its financial powers and increased legislative power to intervene in areas of State responsibility. Centralism appears to be the order of the day.1 Today the Federal landscape looks very different to how it looked when the Australian Colonies originally „agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth‟2, commencing from 1 January 1901.