Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Fourteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Negative Implications in the Interpretation of Commonwealth Legislative Powers

THE ROLE OF NEGATIVE IMPLICATIONS IN THE INTERPRETATION OF COMMONWEALTH LEGISLATIVE POWERS MICHAEL STOKES* One of the bases for the view that Commonwealth powers should be interpreted broadly is the idea that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power. The paper argues that far from being wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power it is necessary to do so in that it is impossible to interpret such grants sensibly without drawing negative implications from them. This paper considers Isaacs J’s argument in Huddart Parker that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power, as it is the most detailed defence of that position, and the adoption of similar arguments in Work Choices. It then considers the merits of Isaacs J’s argument, rejecting it because it is impossible to interpret positive grants of power without drawing negative implications from them in any context and in the Australian constitutional context in particular. This paper looks at how the scope of such implications is to be determined and how constitutional grants of power ought to be interpreted in the light of negative implications. It concludes that it is possible to determine the scope of the negative implications implicit in the s 51 grants of power and to interpret those powers in the light of the implications while accepting that state powers are residual and that their content cannot be determined until the content of all Commonwealth powers is known. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 176 II The Origin of the Argument That It Is Wrong to Draw Negative Implications from Positive Grants of Power ....................................................... -

Australian Political Writings 2009-10

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament BIBLIOGRAPHY www.aph.gov.au/library Selected Australian political writings 2009‐10 Contents Biographies ............................................................................................................................. 2 Elections, electorate boundaries and electoral systems ......................................................... 3 Federalism .............................................................................................................................. 6 Human rights ........................................................................................................................... 6 Liberalism and neoliberalism .................................................................................................. 6 Members of Parliament and their staff .................................................................................... 7 Parliamentary issues ............................................................................................................... 7 Party politics .......................................................................................................................... 13 Party politics- Australian Greens ........................................................................................... 14 Party politics- Australian Labor Party .................................................................................... 14 Party politics- -

The Executive Power Ofthe Commonwealth: Its Scope and Limits

DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY Parliamentary Research Service The Executive Power ofthe Commonwealth: its scope and limits Research Paper No. 28 1995-96 ~ J. :tJ. /"7-t ., ..... ;'. --rr:-~l. fii _ -!":u... .. ..r:-::-:_-J-:---~~~-:' :-]~llii iiim;r~.? -:;qI~Z'~i1:'l ISBN 1321-1579 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1996 Except to the extent of the uses pennitted under the Copyright Act J968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any fonn or by any means including infonnation storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using infonnation publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Parliamentary Research Service (PRS). Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. PRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members ofthe public. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1996 Parliamentary Research Service The Executive Power ofthe Commonwealth: its scope and limits Dr Max Spry Law and Public Administration Group 20 May 1996 Research Paper No. 28 1995-96 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the help given by Bob Bennett, the Director of the Law and Public Administration Group. -

Is Aunty Even Constitutional?

FEATURE IS AUNTY EVEN CONSTITUTIONAL? A ship stoker’s wife versus Leviathan. n The Bolt Report in May 2013, an and other like services,” authorised the federal erstwhile Howard government minister government to be involved with radio broadcasting. was asked whether privatizing the At first sight, it would seem a slam dunk for ABC would be a good thing. Rather Dulcie. How could the service of being able to Othan answer, he made pains to evade the question, send a letter or a telegram, or make a phone call to leaving viewers with the impression that there are one’s Aunt Gladys in Wangaratta to get details for politicians who would like to privatise the ABC this year’s family Christmas dinner, be in any way but don’t say so from fear of the controversy. the same as radio broadcasting news, music, and If only they had the courage of the poor, barely crime dramas to millions of people within a finite literate ship stoker’s wife in 1934 who protested geographical area? against the authorities’ giving her a fine for the This argument has been reduced to a straw man simple pleasure of listening to radio station 2KY by no less an authority than the current federal in the privacy of her solitary boarding house room. Parliamentary Education Office, which asserts on All federal legislation has to come under what its website that Dulcie Williams “refused to pay the is called a head of power, some article in the listener’s licence on the grounds broadcasting is not Constitution which authorises Parliament to “make mentioned in the Constitution.” It is true that, when laws … with respect to” that particular sphere. -

LAYING CLIO's GHOSTS on the SHORES of NEW HOLLAND* the Title Does Not Foreshadow an Ex

EMPTY HISTORICAL BOXES OF THE EARLY DAYS: LAYING CLIO'S GHOSTS ON THE SHORES OF NEW HOLLAND* By DUNCAN ~T ACC.ALU'M HE title does not foreshadow an exhumation of the village Hampdens, as Webb T called them,! buried on the shores of Botany Bay. In fact, they were probably thieves, but let their ;-emains rest in peace. No, the metaphor in the title is from an analogy from a memorable controversy in value theory in Economics. 2 The title was meant to suggest the need for giving some historical content to the emotions that have accompanied discussions of the early period. Some of the figures which seem to have been conjured up by historical writers have been given malignancy but 110t identity. Yet these faceless men of the past, and the roles for which they have been cast, seem to distort the play of life. And indeed, it is perhaps because the historical boxes have remained unfilled, and because the background-the rest of the play and action-has not been fully explored, that some people of the early period, well known to us by name, have been interpreted in the light of twentieth-century prejudice and political controversy. We know all too little about the quality of day-to-day life in early Australia, the spiritual and material existence of the early Europeans, their energies, their activities and outlook. In the first stage of an inquiry I have been pursuing into our early social history, I am concerned not with these more elusive yet in a way more interesting questions, but in what sort of colony it was with the officers, the gaol and the port. -

World Bar Conference

World Bar Conference War is not the answer: The ever present threat to the rule of law Friday 5 th September 2014 1 By Julie Ward ‘In all countries and in all ages, it has often been found necessary to suspend or modify temporarily constitutional practices, and to commit extraordinary powers to persons in authority in the supreme ordeal and grave peril of national war...’ 2 The last time that Australia declared war on another nation was during WWII. We have been fortunate not to have had a recent history of having to defend our territory against attacks by foreign powers. In 21 st century Australia, the only threat of violence on a scale comparable to wartime hostilities is that posed by international terrorism. War has not, therefore, been seen as “the answer” to anything in my country in my lifetime. I propose to approach the question of threats to the rule of law that arise in the context of war by reference to the proposition, implicitly acknowledged by Higgins J in the High Court of Australia in Lloyd v Wallach, handed down at the height of WWI, that extraordinary 1 Judge of Appeal, NSW Supreme Court. I wish to acknowledge the diligent research and invaluable assistance provided by Ms Jessica Natoli, the Court of Appeal researcher, in the preparation of this paper, and to my tipstaff, Ms Kate Ottrey , and the Chief Justice’s research director, Mr Haydn Flack, for their insights on this topic. My gratitude also to Ms Kate Eastman SC for her incisive comments on a draft of this paper. -

Inaugural Speech of the Honourable David Clarke

INAUGURAL SPEECH OF THE HONOURABLE DAVID CLARKE The Hon. DAVID CLARKE [8.11 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I also oppose this legislation. In speaking for the first time I do so with a great and abiding recognition of the responsibilities that my new office places upon me and with the hope that my time spent here will be productive in service to the people of New South Wales. I come to this House as one who by conviction and belief respects, supports and upholds its history and traditions. As a member of the Legislative Council I will resist with all the vigour I can any and all attempts to bring about this House's demise, to weaken its powers or to diminish its stature and traditions in any way. Over the years many outstanding and distinguished members have served in this Chamber. The late Jim Cameron was a member whose values and social beliefs I identify with. He had a unique and inspirational capacity to espouse values in noble and uplifting language as befits such noble values. A former and distinguished President of the House, Johno Johnson, representing an historic political institution of our country, the Australian Labor Party, has also been courageous, forthright and determined, especially in his elevation of the family, his defence of the right to life of the unborn child and his denunciation of abortion. He continues to champion these causes outside this Chamber. I deem it an honour to find myself serving in this House at the same time as Deputy-President Reverend the Hon. -

Constitutional Law Note

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW NOTE Topic 1, 2 – The Structure of Parliament and Legislative Procedures o The Structure .......................................................................................................... 3 o Duration and Membership ..................................................................................... 5 o Standard Legislative Procedures: Commonwealth and States ............................... 8 o Commonwealth Alternative Procedures (section 57) ............................................ 10 o Commonwealth Restrictive Procedures (section 128) .......................................... 13 o Special Procedures for Financial Legislation (section 53, 54, 55) ........................ 15 o State Restrictive Procedures .................................................................................. 19 Topic 3 – Characterisation and Interpretation o Principles of Constitutional Interpretation ............................................................. 25 o The Process of Characterisation ............................................................................. 28 Topic 4 – Financial and Economic Powers o Taxation Power – section 51(ii) ............................................................................. 33 o Grants Power – section 96 ..................................................................................... 36 o Appropriation Power – section 81 ......................................................................... 38 o Corporations Power – section 51(xx) ................................................................... -

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: a Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon*

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: A Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon* The essential and distinctive feature of “a truly federal government” is the preservation of the separate existence and corporate life of each of the component States concurrently with that of the national government. Accepting that a number of polities are contemplated as coexisting within a federation does not, however, address the fundamental question of how legislative and executive powers are to be allocated among the constituent constitutional units inter se, nor the extent to which the various polities are immune from interference occasioned by their constitutional counterparts. These “federal” questions are fundamental as they ultimately define the prism through which one views the Constitution. Shifts in the lens have resulted in significant ramifications for intergovernmental relations. This article traces the development of the Melbourne Corporation doctrine in Australia, and undertakes a comparative analysis with the development of the cognate jurisprudence in the United States. Analysis is undertaken of the major Australian industrial relations decisions, such as the Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria, Queensland Electricity Commission v Commonwealth, and United Firefighters Union of Australia v Country Fire Authority, in this context. But one of the first and most leading principles on which the commonwealth and the laws are consecrated, is left the temporary possessors -

Dyson Heydon Allegations Known to High Court Judges Michael Mchugh and Murray Gleeson 10/8/20, 3�32 Pm

Dyson Heydon allegations known to High Court judges Michael McHugh and Murray Gleeson 10/8/20, 332 pm EXCLUSIVE NATIONAL HEYDON CONTROVERSY Two High Court judges 'knew of complaints against Dyson Heydon' By Kate McClymont and Jacqueline Maley June 25, 2020 — 6.00am A A A Two judges of the High Court allegedly knew of complaints of sexual harassment made against their colleague Dyson Heydon, according to an independent investigation conducted by the High Court that has sparked a national conversation about misconduct in the legal industry. According to the confidential report, obtained by the Herald and The Age, Justice Michael McHugh, who served on the court from 1989 until 2005, and the then chief justice Murray Gleeson, who headed the court for a decade until 2008, were told of their colleague's alleged behaviour. New details from the report reveal Mr McHugh's then-associate Sharona Coutts told the investigator that in 2005 she was at the court when Rachael Patterson- Collins "came rushing - half walking, half running" towards her. https://www.smh.com.au/national/two-high-court-judges-knew-of-complaints-against-dyson-heydon-20200624-p555pd.html Page 1 of 6 Dyson Heydon allegations known to High Court judges Michael McHugh and Murray Gleeson 10/8/20, 332 pm Former High Court judge Dyson Heydon, Former chief justice of the High Court Murray Gleeson and Former High Court judge Michael McHugh. Ms Collins was one of six former associates whose allegations of sexual harassment at the hands of the former judge have been upheld. The report said, "Ms Coutts stated that she could vividly recall that Ms Collins's cheeks were flushed pink, and that her eyes were wide and that she looked scared". -

Same-Sex Marriage, Freedom of Speech and Religious Liberty in Australia – a Critical Appraisal

Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics Volume 7 Issue 1 Religious Liberty Article 4 2017 Same-Sex Marriage, Freedom of Speech and Religious Liberty in Australia – A Critical Appraisal Augusto Zimmermann University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/solidarity ISSN: 1839-0366 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING This material has been copied and communicated to you by or on behalf of the University of Notre Dame Australia pursuant to part VB of the Copyright Act 1969 (the Act). The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Recommended Citation Zimmermann, Augusto (2017) "Same-Sex Marriage, Freedom of Speech and Religious Liberty in Australia – A Critical Appraisal," Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/solidarity/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Solidarity: The Journal of Catholic Social Thought and Secular Ethics by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Same-Sex Marriage, Freedom of Speech and Religious Liberty in Australia – A Critical Appraisal Abstract Passing legislation to approve same-sex marriage presents an immediate challenge to free speech and religious liberty. Unfortunately examples from all over the world reveal that legalisation of same-sex marriage may infringe the fundamental rights of the citizen. -

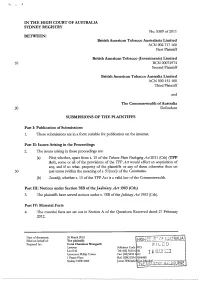

Submissions of the Plaintiffs

,, . IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA SYDNEY REGISTRY No. S389 of 2011 BETWEEN: British American Tobacco Australasia Limited ACN 002 717 160 First Plaintiff British American Tobacco (Investments) Limited 10 BCN 00074974 Second Plaintiff British American Tobacco Australia Limited ACN 000 151 100 Third Plaintiff and The Commonwealth of Australia 20 Defendant SUBMISSIONS OF THE PLAINTIFFS Part 1: Publication of Submissions 1. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the internet. Part II: Issues Arising in the Proceedings 2. The issues arising in these proceedings are: (a) First, whether, apart from s. 15 of the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Cth) (TPP Act), some or all of the provisions of the TPP Act would effect an acquisition of any, and if so what, property of the plaintiffs or any of them otherwise than on 30 just terms (within the meaning of s. 51 (xxxi) of the Constitution. (b) S econdfy, whether s. 15 of the TPP Act is a valid law of the Commonwealth. Part III: Notices under Section 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) 3. The plaintiffs have served notices under s. 78B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). Part IV: Material Facts 4. The material facts are set out in Section A of the Questions Reserved dated 27 February 2012. Date of document: 26 March 2012 Filed on behalf of: The plaintiffs Prepared by: Corrs Chambers Westgarth riLED Lawyers Solicitors Code 973 Level32 Tel: (02) 9210 6 00 ~ 1 "' c\ '"l , .., "2 Z 0 l';n.J\\ r_,.., I Governor Phillip Tower Fax: (02) 9210 6 11 1 Farrer Place Ref: BJW/JXM 056488 Sydney NSW 2000 JamesWhitmke -t'~r~~-~·r:Jv •,-\:' ;<()IIRNE ' 2 Part V: Plaintiffs' Argument A.